By Amy Taubin in the November-December 2016 Issue

Common Sense

American indie axiom Jim Jarmusch talks about the art of routine in Paterson (and the assembly of chaos in Gimme Danger)

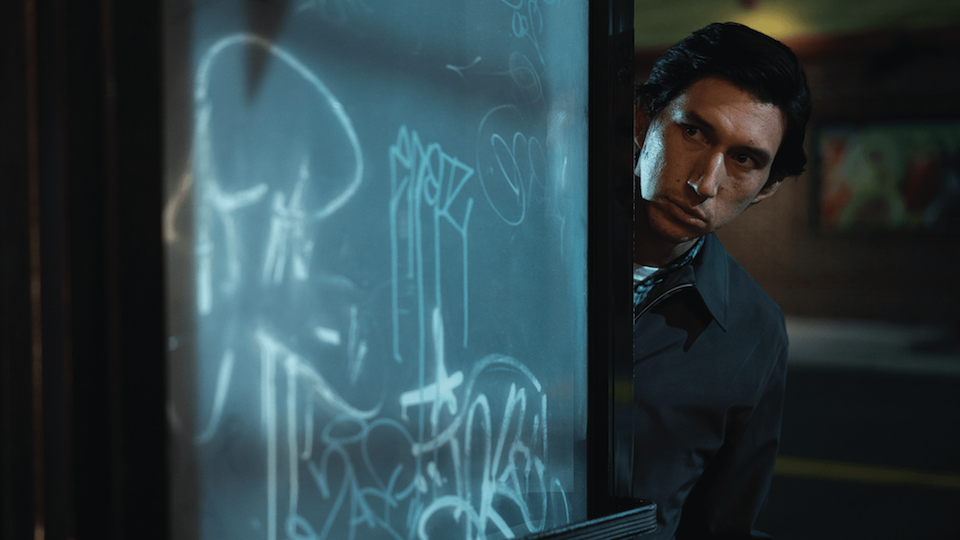

Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson depicts seven consecutive days in the life of Paterson (Adam Driver) and Laura (Golshifteh Farahani), a couple living in Paterson, New Jersey. Paterson also shares its title with the poem by William Carlos Williams. This interview between Jarmusch and Amy Taubin took place during the 54th New York Film Festival, where the film had its New York premiere, as did Gimme Danger, Jarmusch’s documentary about Iggy Pop.

From the November-December 2016 Issue

Also in this issue

So let’s talk about Paterson. You gave a cover quote for the reissue of Jonas Mekas’s book, Movie Journal. Was the book important for you in some way?

Yes, I had read things off and on.

Did you read Jonas when he was writing in the Village Voice? I’m asking it in relation to poetry. Jonas has that line, something like, “Avant-garde film is poetry. Narrative cinema is prose.” So I was curious about you and your relationship to poetry and film. Did you ever write poetry?

Yes.

Seriously?

I came to New York and I studied at Columbia with Kenneth Koch and with David Shapiro, figureheads of what we call the New York School. And Ron Padgett and David edited an anthology of New York poets in 1975 that was kind of the bible of this school of poetry. The New York School particularly was really, and remains, very close to my heart. That’s Frank O’Hara, of course, John Ashbery, James Schuyler, Ron Padgett, David Shapiro, Kenneth Koch, incredible poet, Joe Ceravolo, Frank Lima. Some of their poetry is concurrent with the Beats, whom I love in a different way, but to me, the New York School, those are my godfathers.

And also for film too, in a way. Because their poems are funny, their poems are personal. Frank O’Hara wrote this very beautiful manifesto called “Personism” in which he says: “Don’t write poetry to the world. Write poetry to one other person. Write a love note to someone you love, or write a little poetic letter to someone you know.” So that’s been really inspiring to me and I’ve tried to make films that are not shouting out from the mountaintop to all of the world, but more like little letters out to someone I care for. They’ve really inspired me throughout.

I write poetry now and then. I don’t really show it to people. I’ve shown a few over the years to David Shapiro. He was my teacher. But yeah, I just love those guys. And as far as Paterson, somebody said it’s like a poem in the form of cinema, but I think it’s more like cinema in a poetic form. Because it’s a film, and I know what Jonas means because poetry is allowed to be abstract where prose is not in the same way. Poetry, even how it’s placed on a page, even if you go back to Apollinaire—Calligrammes—who played a lot with the way the way things are on the page so that the spaces become equally important… That’s very abstract. Prose can do something like that, but it’s not the same way. So I understand Jonas’s observation of a certain form of films being freed of prosaic restraints. Poetry can do that. I’ve always loved poets since I was a teenager, because I discovered Baudelaire and the French symbolists, and of course Rimbaud a little later, and then—I discovered all this in translation—Rilke. And I discovered Walt Whitman, Hart Crane. And then Wallace Stevens, leading to, of course, the New York School.

And what about William Carlos Williams?

William Carlos Williams is kind of the avatar, on one level—the godfather of “Personism.” We used a very obvious one of his poems in the film, “This Is Just to Say,” which literally was a little note left on a table. “I have eaten the plums you were saving for breakfast.” It’s the precedent for what Frank O’Hara was proposing poetry to be. William Carlos Williams is really important in that lineage. And of course he wrote the long, more abstract, book-length poem Paterson, which frankly, I don’t understand a lot of.

Paterson

What do you mean, you don’t understand?

I don’t quite connect with it. It’s a bit too abstract, or maybe a bit too philosophical for me somehow. And yet, it was a big inspiration for the film Paterson because the beginning of the poem is using the metaphor of Paterson, the city, being a man, and he even describes the formation of the rocks that form the waterfall as a reclining figure. So it was like, “Wow, I could make a film about a man named Paterson in Paterson, and he’s a working-class guy who’s a poet.” Now, William Carlos Williams was not working-class, but he had a job, he was a pediatrician, and he wrote poetry on the side. He delivered over 2,000 children in his lifetime. I love that poets have other jobs. Frank O’Hara was a curator of the Museum of Modern Art, Wallace Stevens was an insurance executive—when he won some kind of award, one of his colleagues said, “Wait a minute, Wally writes poetry? I had no idea.” One of our greatest poets ever in America! And this is true of many writers—Robert Walser was a bureaucrat, like Kafka. You’ve got to have another job to do this stuff. No poets ever did it for the money.

After my first visit to Paterson 25 years ago or so, I started making vague notes toward this film. I went to check out this place where this poet lived. I went there for a little day trip, and I went to the Passaic Falls, sat right where Adam Driver—Paterson in our film—sits, and I walked around the industrial buildings. It was because of Williams, and also that Allen Ginsberg grew up there, and there were all these weird connections. William Carlos Williams was Robert Smithson’s pediatrician.

Really?

Yeah. That kind of blew my mind. Because I love Robert Smithson.

So his famous 1967 Artforum photo-essay, “The Monuments of Passaic,” was based in a bus ride through a place where he actually had lived.

Yes, he’s from that same area. Also the Lenape tribe, the indigenous people, had an encampment or a village right near the bottom of the Passaic Falls. That must have been an incredibly beautiful place to live. But that’s before Europeans even came here. Paterson’s history is fascinating. Alexander Hamilton envisioned it as this utopian, first industrial city, which it became, and then it became a hotbed of anarchism, and strikes of textile workers. In 1835, there was a strike of thousands of textile workers. Two thousand of them were Irish children, and they were striking because they were working 13-hour days, six days a week. And they practically lost the strike, but they got reduced to 11-and-a-half hour work days. There were also a lot of Italian anarchists.

I used to visit Paterson because my father was garment manufacturer, and he would go to Paterson to buy silk.

Because it was the silk capital starting in the 19th century. It’s a remarkable place, but now, it’s a rough place…

I was leading up to that. All we hear about Paterson today are terrible headlines on the evening news about fires and murders.

Or Donald Trump said that after 9/11 all the Muslims in Paterson were cheering. It’s his fantasyland. Paterson is a rough place, and our film is not a social document of Paterson. It’s an imagined Paterson. But we are respectful to it visually and to its ethnic diversity, because it’s incredibly diverse. It has the largest Arabic or Middle Eastern population per capita of any city in America after Dearborn, Michigan. And a huge South American population. Obviously, there were a lot of Irish and Italians, and then post Civil War, a big African American population. It’s incredibly diverse still.

To keep it on poetry for a minute, I looked through Paterson again before I saw your film. But the Williams poem I landed on was “The Red Wheelbarrow,” just because of the way it’s set up on the page.

Yeah. Perfect. The breaks, the way it looks, and it’s so beautiful at being a tiny detail of mundane, something just noticed, something of no real significance. In Toronto, we had a Q&A and they kept asking about the significance of certain things in Paterson, and I said: “I think we’re going for the anti-significance here.” I thought it was so funny, because the film is about things not being significant. But anyway, “The Red Wheelbarrow”: case in point. It’s beautiful.

I thought about that poem in relation to him coming home every day and straightening the mailbox. How do you figure out where you place the hilarious reveal? When did you decide the day on which we see that the dog is the culprit?

It’s not in the writing, it’s in the editing. For me, filming is capturing things, and the editing is where you form a film out of them. Obviously, I have a script and ideas, but you really have to find it in the editing. Another example is, there’s a dumb, dumb joke about the bus bursting into a fireball. When an older lady says it, getting off the bus, it’s mildly amusing. Then it’s repeated by Laura, and it’s like, “Well, that’s kind of stupid.” But then they repeat it again, a third time, and for me it becomes funny again. But you don’t know until you’re playing with it in the editing. Because of the way the film is shot, those things are modular and could be moved. For example, in the middle of the week, he goes to the bar, and nothing’s going on. He just looks around, that’s it. That was originally, in the script, on Thursday night. But then it didn’t build right, so it became Wednesday night. Or at what point should we see the dog come and mess up—tip—the mailbox? I never know exactly until, really, in the editing. The twins weren’t even in the script, it just occurred to me while we started shooting because a couple of extras happened to be twins. And I thought, “Ah, yeah.” So I put that in there. I had more twins, but then, how much is too many twins? So I had to take some out, or decide, where should they go. For me, a film is formed in the editing room because I only write one draft of the script.

Paterson

Really?

Yeah, I don’t rewrite. But then, when we start working… Okay, I’m working with Mark Friedberg, and he’s the incredible designer, and we’re getting locations, and I’m making notes. And now I have cast Golshifteh Farahani and Adam Driver, so I’m going to change some things. Even as we’re shooting, I’m like, “Oh, maybe I need twins.” And then I see extras that are twins. So I keep working on it, but the final draft is in the editing room. All the rest is gathering. But I will never write a script, and then show it to people, and then have to rewrite it… I don’t do multiple drafts. It’s the starting point, the map. But it’s going to get better, I hope.

Because the auteur thing is nonsense. Film is so collaborative, and especially in my case, because I have artistic control over the film. That means I choose the people I collaborate with—we’re making the film together. I use “a film by [Jim Jarmusch]” in the credits to protect my ability to choose my collaborators in this world of financing and using other people’s money. But we’re collaborating all the time, so the film is evolving each day we scout, and then each day we shoot, and then if we rehearse, whatever that might mean, it’s just changing, changing, changing. They have this thing, traditionally, where they put different colored pages in the script in pre-production as you’re going along. “Oh, that was a new idea, so those are pink pages.” My final script is multi-colored, because I keep adding, changing—take this scene out, move this one around. For the production, they need to keep track of it. And I love these colored pens that write in four colors, so I make notes all over in different colors. My shooting script is very colorful.

And your amazing editor since Only Lovers Left Alive…

Affonso Gonçalves. Man, I love him. I worked forever with Jay Rabinowitz, who I loved working with. He wasn’t able to do Only Lovers, so I got to meet Affonso. And he’s very musical, too, like Jay. So I don’t have a music editor, ever. It used to be Jay who did it, and now Fonsie does it. Why compartmentalize it?

It seems like an incredible match.

And we work fast, too. He made…

Beasts of the Southern Wild?

Beasts he had to sort of find the film in what he had, and he also cut Winter’s Bone, which has a very beautiful rhythm to it. Of course, he cut Carol. He’s doing the new Todd Haynes film. He’s just incredible. It’s a pleasure each day. But editing’s always been that way for me, ’cause that’s where you make the film. And even if it’s problematic, then you find your way, you try different things, you solve a problem you have in the film.

At what point did you think that Adam Driver and Golshifteh Farahani could be a couple?

First, I did not write the film for characters, which is unusual for me. I definitely wrote Only Lovers Left Alive for Tilda [Swinton]. Then I found Tom Hiddleston. I hadn’t seen a lot of Adam, only smaller things that he did in Inside Llewyn Davis, Frances Ha, and one episode in Girls.

He was the best thing in Girls.

He was fantastic. Then I heard some interviews with him, and I liked how he seemed so open and sincere. He wasn’t trying to pump himself up. He seemed aware of his own fragility, in a way. Then talking with him, I just knew, “Oh, this guy’s fantastic.” And he was in the military, and he also went to Juilliard. And this is a film about a bus driver, who’s a kind of refined poet. I also love that Adam will not see a film that he’s in, like Robert Mitchum, who never would. Adam won’t because Adam knows that his gift is reactive, not analytical, same as me. For him to see himself would mess him up. “Oh God, I’m looking at my posture, and how I walk.” He doesn’t want to think about that. So he’s not seen Paterson. He hasn’t seen [the new] Star Wars. And he was lovely to work with. He’s quiet, but he’s got a very good sense of humor, and he just wants to react. He’s very observational as a person.

In the first draft, Laura was blonde, but Sara Driver suggested Golshifteh whom I loved in Half Moon and a few more recent films. So I cast her just because I loved her, not because she was of Persian origin. I told Adam and Golshifteh, “If you guys want to have a backstory of how you met, or whatever, that’s fine but do not tell me, I don’t want to know anything about it. I want to start with day one, Monday morning, you’re in bed together. What I know about you starts now.” And they were like, “Okay, fine.” But then, I wove Persian things in, a little music she listens to, some of her designs. Some little photograph she sees.

What’s so interesting to me about them as a couple is that she is the more active one. Her relation to her expressivity is out there, and his is all inside. He gets the subjective image superimpositions.

He likes routine, because routine allows him to drift. Because he doesn’t have to think about what clothes does he wear each day, what time does he go to work, what is the route of his bus. Even walking the dog, going to the bar is part of his routine. Everything is laid out for him, and that lets him be a poet, because within that routine, he can observe, he can be an antenna, he can drift, he can listen to people, he can write his poems by the waterfall. He needs that.

And she has so many things going on, you don’t know what’s going to be next. I love when she says at one point, “Guess what I did today?” And he said, “Uh… plant an unusual vegetable garden in the backyard?” She says, “No, silly, you’ve got to do that in the spring!” Like, that’s a possibility! Think of all the things she’s doing and we only see her in one week. Imagine a month’s worth of Laura. She’s very busy. I talked to a feminist French journalist in Cannes, who said, “Your film’s a throwback to ’50s domesticity, et cetera, with this character of Laura.” And I was like, “Wait a minute, she makes her own decisions, she lives the way she wants. She wants to make cupcakes, which might make money for them. She’s not oppressed by a male figure. She’s totally free. So why are you defining her only because her environment is basically domestic, how is that anti-feminist? Are you against every working-class female on the planet who right at this moment might be washing her children or making food for them, or are they anti-feminist? Are they oppressed? Should they be working for a corporation, wearing a business suit, and then you’d be okay?” It was interesting, because I understood that domesticity set off a reaction in someone. I’m a feminist!

I like the character of Laura, and I think it’s interesting this difference you mentioned—that Paterson doesn’t even take in all the things she’s doing because he’s kind of spaced out. She tells him three times about the cupcakes and still he asks her, “Hey Laura, what’s all the flour for?” Because he needs to drift away. That’s his gift. That’s who he is. And she’s very accepting of who he is, in the same way he is of her. And that, to me, is a love story. There’s no conflict here, really. They love each other for who they are, and they’re different. That’s almost getting too analytic for me, like what’s the film about. There’s that part of it. There is love in the story.

Paterson

Oh, it definitely is a love story, just like Only Lovers Left Alive is a love story…

Yes, they are…

Let’s talk about the cinematography. I didn’t realize it was shot digitally when I saw it the first time. It’s so beautiful.

Fred Elmes is just incredible. He’s been using the Alexa Digital Arriflex camera for quite a while now. He knows I love film material, as does he. Only Lovers was digital, but that was different, because that was set at night, and digital at night can be very beautiful because you use less light and you get really beautiful, rich blacks. Digital in the daylight gives me a headache because of the depth of field, and because of the skin tones in daylight—I don’t like it. But Fred said, “Okay, we set up the parameters, we program in a certain look in the same way we used to, when we picked our film stocks, and we have a variety of options. So we pick our exterior film stock, and our interior film stock if they’re not the same. We know there’s a look we’re going for from the moment we buy our film materials. In the digital, we have all our raw information, but we also program in, in advance, a look that we like. Is it warm? Is it cool? What kind of feeling are we looking for?” And Fred and I also talked with Mark Friedberg about that in advance.

Fred knows I hate this depth of field. At some point, we had so much neutral density filtration in front of the lens that it looked like it was black, because I want the lack of depth of field. So that if you have two people in a frame in a close-up, one of them is out of focus. That’s beautiful. Fred knew how to do that. Fred guided us to find it, because he’s been thinking about it for a long, long time now, shooting digital. It really made me realize that these are all tools. Digital is not as magical as film, but it has magical capabilities too. And we did something I almost hesitate to reveal. We did a very tricky thing. I said to Fred, “I want the film to have a feeling of being vignetted somehow without actually seeing any vignetting.”

Fred is just so incredible, but what incredible collaborators we talked about! Affonso Gonçalves, Fred, Mark Friedberg is just incredible to work with. Mark is not just the production designer, he puts his soul into everything. Fred wasn’t around when we started scouting because Fred was shooting something. So Mark and I would just go out by ourselves and start location scouting, very early. Just the two of us, driving to Paterson. Mark would drive. And he’d take pictures while driving. He is just an incredible person. His hand is in so many things. He helped me pick the books that are seen in the little writing area in the basement, and he came up with all these possible techniques for Laura to try to do. That’s his idea, where you paint with bleach, and then it gets lighter a second or two after you apply it. Mark brings so many things to the film.

And I didn’t know Catherine George, the costume designer, but Tilda Swinton, who is my guide in so many ways—I wish she were the queen of the universe—she said, “Oh, you’ve got to meet my friend.” I used to love to work with John Dunn, the costume designer, but he wasn’t available. And Tilda said, “You’ve got to meet Catherine George.” So I met her, and what another gift of a collaborator. I feel so lucky just to get to work with these people. And our producers were just great. Carter Logan’s my colleague for a long time, and Josh Astrachan, who worked with Altman… And our whole crew—everyone was fantastic. And we haven’t even mentioned this lovely dog actor, Nellie, who we lost. What an actor, too. And all the vocalizations, all the little sounds are all her.

They are?

Yeah, they don’t come from any other dog, or any other thing. She did her own ADR, her own looping. We just edited it in. She was fantastic. A real sweetie, too. We weren’t allowed to interact with her, the crew. You have to keep a distance: she could interact with the two actors, but you can’t let her get close to anyone because she has trainers that she’s obeying. Everyone wanted to be friends with her, and we had to let her be a diva.

One other thing—the scenes in the bar. The actor who plays the guy who gets his heart broken, William Jackson Harper is amazing.

He’s so lovely. I love the scene where he says he’s an actor. I can’t stop laughing.

He has fantastic timing, and it’s all real.

Oh yeah. He’s wonderful.

The bar was such a familiar place, and I so believed in it. It really felt like those people are in that bar every night.

That’s good to hear. It’s hard for me to know that, and that’s a big concern of mine, and I can’t know it, because… I joke with people that come up to me and say, “Oh, I really like your film.” And I say, “Wow, that’s good, ’cause I haven’t seen it.” Because I can never see it. So I don’t know. I hope it’s not corny or fake. It’s hard for me to know.

No, it’s not at all. You do believe that these people are in that bar and that this is routine, and when they’re supposed to know one another, they do know one another. And that’s all absolutely rare. I mean, I don’t believe that in Friends on TV, that those people ever said a word to each other except on the set.

Well, I’m glad to hear you say that. I’m very happy, too—that bar we shot was the bar that was in Trees Lounge, Steve Buscemi’s film. Years ago.

You used the same bar?

The same bar. Because I couldn’t quite find a bar, and then, you know, Steve and I are very close, and I think he said, “Well, you should check out the one we used. I think it’s still there and everything.” So then we checked out Trees Lounge.

Where is it?

It’s in Queens, actually. It’s fantastic. And the owner was really nice, accommodating. But I like that it’s in Steve’s movie from 20 years ago. So it had a good vibe, just for me, for that. It still had some of Steve’s molecules or something in there, somehow. At least, cinematic molecules.

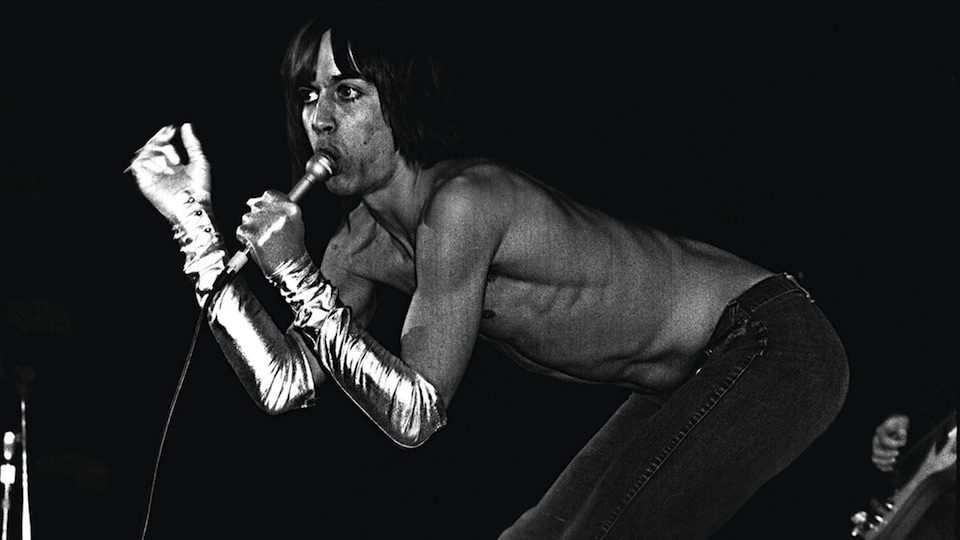

Could we talk a little bit about Gimme Danger? Because you were working on it at the same time as Paterson.

Jim Osterberg—Iggy Pop—and I have been friends for 25 years. About eight years ago he said, “I know you love the Stooges. And I kind of wish, if someone would make a definitive movie about us, it would be you.” The next day, I was trying to figure out how I would approach this. So I started getting ideas for a structure, loosely, then a plan of some stuff to shoot, and who I would shoot. I did not want to shoot anyone that wasn’t family, wasn’t the Stooges. Which includes Kathy Asheton, the Asheton sister, and Danny Fields. I thought of Bowie and John Cale, because I love them. But I realized, you know, if you shoot them, you’re going to use them, and do you really want to use them? No, I don’t, because they’re outside the Stooges. So I kept that as a strategy.

I started working on it, and then I ran out of money. Carter Logan was the only real producer of this film, and he told me—this is before we shot Only Lovers Left Alive—“Jim, you’ve spent almost 40 grand of your own money. You’re going to run out of money.” So we stopped, and then after Only Lovers, started in some more. Bart Walker, my angel, helped us meet this incredible guy, Fernando Sulichin, who financed the film in the end. Then we paused to do Paterson. A funny thing is that the reference to Iggy Pop in Paterson is real.

You’re kidding!

It’s not made up. No, I wouldn’t make it up. The Girls’ Club of Paterson in 1970 proclaimed him the sexiest man alive. I really get a kick out of Doc saying, “Okay, Iggy Pop on the wall.” Because that was really true. Anyway, it took a year and a half to clear all the rights for Gimme Danger. We had great people working. Arielle de Saint Phalle, who I work with, was incredible. We’d get photos, and then they’d ask for too much money. We can’t do it, so okay, take them out. Then she would relentlessly find other things to replace them, and negotiate, and track down guys living in a trailer on the south side of Santa Fe that don’t even care anymore. But that took a year and a half.

But it’s the way the film’s made. It’s a collage of nonsense. Kind of like the Stooges. It’s sort of messy and wild and collaged. And I’m very lucky because I only made one other music film, Year of the Horse, with Crazy Horse, and Neil asked me to make that one also. And I love Crazy Horse, and the Stooges for me, that’s in my soul. It’s a kind of fan film, not an innovative work. I got a little frustrated, actually: while making it, I saw the film 20,000 Days on Earth, a film about Nick Cave.

Gimme Danger

Oh, yeah.

It is a beautiful film because a lot of it’s not true, so you define someone’s truth by not being truthful, and it’s a portrait of Nick Cave that’s so true by parts of it being fabricated. I loved it so much that I thought, “I’m just going to put the Stooges film in a drawer.” Because that film’s very innovative. But then I thought, “Okay, well, they did something very unusual, and ours is not intended to be that. It’s a celebration of the Stooges, and that’s its intention, so don’t worry about it.” But it did throw me for a loop because I love that film.

And now there’s a lovely new film called Danny Says about Danny Fields. I laugh my ass off watching it because Danny Fields is so unfiltered, incredibly opinionated, so funny and fantastic. And I love Danny Fields. In a way, I think all the things Danny Fields brought to light, without them, I might be a refrigeration repairman. I wouldn’t know the MC5, the Stooges, all these things he did. And he did none of it to become rich or famous, Danny Fields. He did it out of interest. He’s a real character. I was laughing throughout so hard. I just saw it the other night, but it was a real pleasure, because these kinds of characters are just invaluable, people like Danny Fields.

Maybe if I were younger, I’d know if there were others like them around, but I don’t think there are.

It seems less and less. At the end of Danny Says, he’s talking about how, “Well, sometimes a lifetime isn’t long enough for the good things to catch up and be appreciated. And so you have to accept that. Don’t worry about that. That’s just the way it is.” He’s just undaunted by that fact. Just to have someone say that, and see how he lived his life—he doesn’t care about getting rich, or even being famous by this film. It almost makes him cringe a little, because that’s not his thing. He’s just a real appreciator of things. And he helped bring them to light, so he’s like a gift. But it seems that there are fewer and fewer people like that.

In a way, what you just said is what Only Lovers Left Alive is about. It’s only because they have that incredible span of time that they can see the relationships, and they can unearth this stuff.

Yeah. I’m a self-proclaimed dilettante, and it’s not negative to me, because I’m interested in so many things, from 17th-century English music, to mushroom identification, to various varieties of ferns, to all kinds of stuff. How can I, in one lifetime—I could be like Adam and Eve in Only Lovers, I wouldn’t be a dilettante, because they actually know. He knows how to build a generator, and she knows the Latin identification of everything. But I’m a dilettante because I don’t have enough time. And there are too many incredible things that I get attracted to, and so my head’s always spinning around. But that’s okay. Being a dilettante is helpful if you make films, because films have all these other forms in them. I’ve been finding more and more a lot of great directors I love were dilettantes or are. Like Nick Ray, prime example. Studied architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright, had Bertolt Brecht crash on his sofa, had a radio show of Appalachian music and rural blues in the ’30s, was a painter, read voraciously, knew all about baseball. I know Howard Hawks had an incredible variety of interests. And Buñuel.

My thing is dilettantism, amateurism—I believe that I’m an amateur, because amateur means you do something for the love of a form, and professional means you do it for your job, you get paid, and nothing against that!—and variations. That’s my holy trinity lately of what my defining priorities are: being a dilettante, being an amateur, and appreciating variations in all expression. Because I love variations. To me, it’s the most beautiful form, to accept that all things are really variations on other things.

The form of this film is all…

Completely, because it’s seven days in a week. It’s just variations on one after the other.

Closer Look: Paterson opens on December 28.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.