By José Teodoro in the November-December 2016 Issue

The State That I Am In

In Neruda and Jackie, shape-shifting filmmaker Pablo Larraín portrays two national icons through refracted storytelling and unexpected emotion

The back-to-back December releases of Pablo Larraín’s Neruda and Jackie constitute a juncture, a pivot-point that renders the director’s purposes both more defined and more elusive. The first film concerns the mythos of his native Chile, the subject of repeated, cataclysmic interference by the United States; the second concerns the mythos of the United States and a cataclysm on its own soil. The following conversation (conducted during the Toronto Film Festival) contains some debate about the nature of what binds these films and Larraín’s work generally. We can at least agree that, unlike nearly every contemporary Latin American auteur, Larraín’s directorial signature isn’t a matter of consistent visual style. Spanning the baroque, the austere, and the oneiric, the aesthetics of his films are case by case, precisely drawn from the disparate dictates of the material; rather, Larraín’s signature is rooted in a regard for history and culture that is arduously invested in re-examination and devoid of sentimentality. The grotesque is never far off in Larraín. Even the Oscar-nominated No, his most overtly celebratory narrative, is as tainted with sober cynicism as it is tinted with a sickly pinkish hue.

From the November-December 2016 Issue

Also in this issue

Larraín’s prior films include Tony Manero (2008), about an impoverished, sociopathic disco savant (played by the brilliant Alfredo Castro) angling for minor celebrity during the darkest years of the dictatorship; Post Mortem (2010), in which a mortician (Castro) perilously in love with a burlesque dancer is tasked with performing an autopsy on Chilean President Salvador Allende; No (2012), which dramatizes the 1988 plebiscite that brought an end to the Pinochet era from the perspective of the marketing wizards (again, Castro, and Mexican superstar Gael García Bernal) on each side of the campaign; and The Club (15), a caliginous inquisition drama about disgraced priests residing in a remote seaside retirement home.

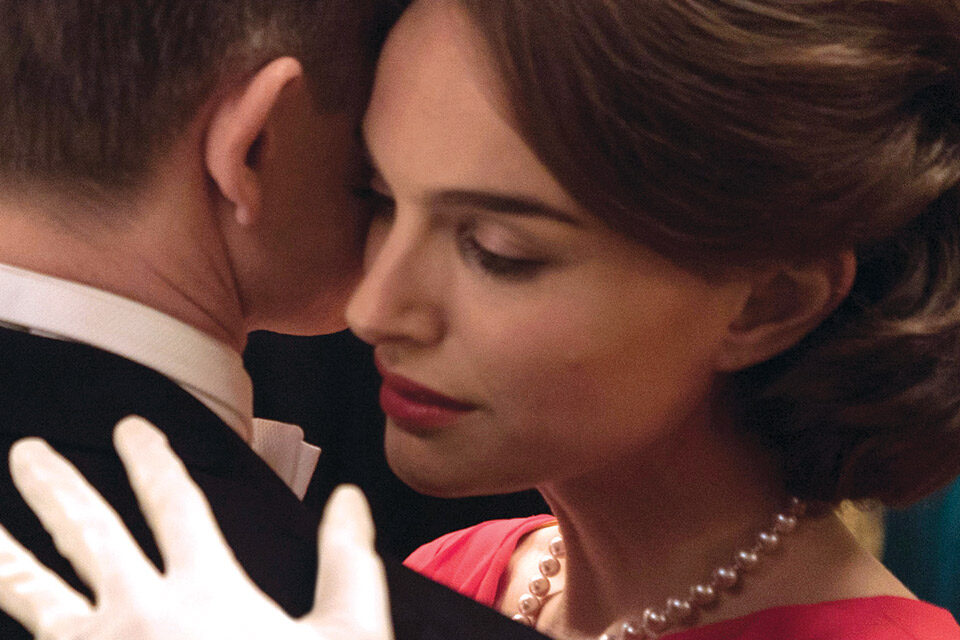

Neruda is just as irreverent as its predecessors, and Jackie just as morbid. The former is less an homage to Chile’s most beloved poet than it is a postmodern policier about the politics of personality and the communist purge that sent Pablo Neruda into hiding. Neruda’s protagonist isn’t even Neruda; instead, the film hews close to one Óscar Peluchonneau (Bernal, at his most transfixed and waxen), the detective leading the hunt for Neruda and impelled by his own delusions of grandeur. Not unlike the bounty-seeking antihero of The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Óscar senses destiny drawing him toward his prey, whose mythic allure he will absorb by virtue of their inevitable contact. Meanwhile, coming just in time for an especially despairing election year, Jackie revisits the immediate aftermath of the Kennedy assassination through the eyes of America’s most iconic widow, played by Natalie Portman with an addlepated blend of trauma and tenacious poise. Jackie is an eerie, and in some ways surprisingly earnest, portrait of a queen forced to fuse personal and public grief as Camelot vanishes from under her feet.

Jackie

At one end of your filmography we find Fuga, your 2006 debut, which still feels like an outlier. At the other lies Jackie, your first non-Chilean, English-language film. In between you have made five features that seem organized around a critical investigation of Chilean history and culture. Were those films intended to be part of a larger project?

Look, man, I never planned anything. Okay, I planned the first one. I called my two brothers, both of whom are lawyers, not filmmakers, but I wanted them to produce it. They agreed and were excited. Fuga was an expensive movie for our circumstances in Chile back then. It did well at the box office. It got awful reviews. I wasn’t sure how to deal with it.

How do you feel about it now?

I haven’t seen it since we made it. Probably I should. My older brother moved on. He now does political analysis. He’s on the liberal right, but that’s another story. My little brother said he wanted to do more. Since then we’ve produced 20 movies together, films by Sebastían Lelio, Sebastián Silva, Marialy Rivas. But, to go back, sometime after Fuga I’m in Spain, at the Museo Reina Sofía. I find there this big Taschen book of photography. I’m leafing through it, kind of bored. I see this picture of this super-skinny guy in his fifties, sitting on a sofa, smoking, staring out the window. I start thinking, “Who is this man?” He could be a dancer. And a serial killer. I’m thinking about Saturday Night Fever, which was released in Chile in 1978. I’m wondering if this could have a political dimension, and: Tony Manero. We shot it very quietly. We went to Cannes and had some success there.

Then I’m at the Turin Film Festival. Someone from the press asks me about Allende. They think Pinochet killed Allende. I explain that this isn’t true. Allende shot himself with a weapon that Fidel Castro gave him. Even Allende’s family has admitted this publicly. It’s not like I’m making it up. But there, in Turin, I find myself back at the hotel, Googling away, making sure I’m right to say this in public, and the autopsy report comes up. I read it. It is a very technical thing, like any autopsy report, but I’m finding it to be, in its medical language, a sort of poetic description of my country. Out of that came Post Mortem.

Then Antonio Skármeta writes this play about the plebiscite. He says why not make a movie. So we make No. While we’re making it, it occurs to me that we have some kind of trilogy. I never planned it.

Neruda was a parallel project that we were developing a long time. I didn’t want to make it. I thought it was impossible to make a film about Pablo Neruda. Eventually we found a way to dig in and produce what we like to call an anti-biopic.

I was going to say, Neruda really isn’t about Neruda.

It’s about the Nerudian. Neruda was a lover of food, a great cook, an expert on wine. He travelled the world collecting things. He was a lover of women, a communist, a politician, a senator, and the most amazing writer of our language. How do you depict such a man? We found out about this period when he escaped from the cops. Yes! So we bring the cop into the story and develop the script around him. But this was going to be a big movie for the Latin American reality. Big budget. It was delayed because we had to wait for Gael. It was also a five-country coproduction, so it took some time. At a certain point I realize it’s going to be another eight months before we can get started and I’m unemployed. What am I going to do? I can’t just go home and cut flowers, though I love to do that. So I do a theatre play, and I get this idea. My brother says, “When do you want to shoot it? After Neruda?” I say, “No. I want to shoot it now. I want to write it and go into pre-production in three weeks.” So we write the movie, me and Guillermo Calderón, who wrote Neruda, and Daniel Villalobos, a film critic and novelist, in three weeks, then shoot it in two and a half weeks. In a month and a half we have material for a movie. That was The Club.

That just leaves Jackie.

We go to Berlin with The Club. We get an award. At the after-party I meet Darren Aronofsky, who was head of the jury. He asks me to read something. He sends it to me and it turns out to be a script I read five years ago. And I liked it. I read it again and I come to Darren’s office and I ask him, “Man, why do you want a Chilean to do this? You’re crazy.” He laughs and says that he thought I could bring a good take on this. I was intrigued, but I said I would only do this with Natalie Portman. He laughs again. He tells me he’ll set up the meeting and then it’s my problem. We meet and I tell her, “If you don’t do this movie I’m not doing it either. No pressure, but that’s how it is.” Natalie asks to see my movies. We set up screenings. I was scared. Here’s Natalie alone in a cinema watching The Club! We meet again. We have another draft in which I had [screenwriter] Noah [Oppenheim] remove all the scenes without Jackie. Natalie accepts. I honestly didn’t expect someone like her to work with someone who made the movies I made. But this says a lot about her, that she’s willing to take risks with people. Darren, meanwhile, allowed me to make the film with total artistic control, which is very hard to get today on a movie like that. So we were setting up Jackie while I continued to shoot Neruda. Then we were in Paris where I was editing Neruda while shooting the interiors for Jackie. We finished Neruda for Cannes, and then after Cannes I finished Jackie, and now I’m talking to you.

Neruda

Why did it have to be Portman?

It was her mystery. You sit her in front of the camera, dress her however you need to dress her, get her to look however she has to, ask her to describe everything she feels and everything she’s thinking, and you will still wonder what’s going on. That’s her mystery. That’s a resource in cinema. You never get all the answers. If you do, the game is over.

From the beginning of Jackie, something that struck me was how you frame the reverse-shots between her and the journalist not over the shoulder but, rather, head-on, confrontational.

Stéphane [Fontaine, the cinematographer] and I photographed that sequence with two cameras. We put them together, almost touching, facing in opposite directions, an operator on each side, the actors looking right into the lens. It had to be super-frontal. You can’t hide. I thought it would be more interesting to expose the characters as much as possible right away, put it all on the line. We shot those sequences at the end of production, so Natalie had fully absorbed Jackie. She was in full control.

The feeling is very different, of course, by the time we arrive at Jackie’s coda. Which is pretty hypnotic. I couldn’t tell you if this sequence runs five minutes or ten—

It’s seven minutes and 40 seconds, man.

In those seven minutes and 40 seconds it feels like your heroine reaches some sort of state of grace in her mourning. You achieve a kind of pure portraiture. Which inevitably made me think of Warhol.

You know what Warhol was working on when he died? If I remember it right, he was working on Jackie Kennedy with the veil. But that’s not what I was thinking of. I felt I wanted to arrive at an illumination moment. Not a moment where we all hold hands and sing, no. I just felt that the movie went into this absolute darkness and needed to reach a very bright moment. It’s not even hope. It’s about a woman who recognizes the moment she’s living through, the terror, and is able to fully inhabit it.

Perhaps what I’m feeling is a conflict between Jackie’s personal, internal grief and the very public grief she’s duty-bound to perform. This moment of grace is the moment when personal grief and public grief find a way to coexist.

Yes. The public self and private self come to a point where they are no longer two selves. It’s maybe also a matter of realizing you’re in danger and arriving at the place where you learn to live with it.

Jackie is intimate and isolating. Neruda, on the other hand, feels very open and inclusive. The party scene, the brothel scene: your Neruda is poised among his admirers like a religious figure in a Renaissance painting. Though not a static one. In my memory the camera is almost always moving.

I never moved the camera like this in my life. For the first time, we had access to all the grips we needed. We had cranes, Steadicam, dollies, and track. The camera has an energy that’s like reading. Neruda’s poetry is about rhythm. After reading you still feel the motion. While shooting, his poetry was all over the place. You’d be sitting on an apple box and you’d spy a poem under the tripod. You’d be on a cigarette break and someone would pick up a book of Neruda’s work.

Jackie

There is indeed a lyricism, as well as a swaying, or sense of intoxication.

I have to tell you something incredibly sad. Two weeks ago our Steadicam operator, Darío Triviño, who shot 90 percent of Neruda, went to bed and never woke up. He was 45. Usually a Steadicam operator can sustain a shot for, say, four to seven minutes. Some can go up to nine minutes. This guy could do 10, 11. He was a master. To make these shots in that aspect ratio with these old lenses is very hard. It’s like you’re on a ship. Very hard to sustain the right horizon. Darío had never read Neruda in his life, but by the end of production he had memorized several poems. He was infected by the Neruda virus.

It’s interesting to learn how much Neruda and Jackie overlapped. I’m sure it’s not lost on you that your first non-Chilean film is being made by the country—is about the country—that looms in the periphery of your previous films, the same country that backed the communist purge from which Neruda runs, that backed the coup that ushered in the Pinochet era depicted in Tony Manero, Post Mortem and No.

It’s the country that keeps sticking its nose in my country, man.

In Neruda, the titular character is portrayed quite irreverently…

We don’t build monuments, man.

…while Jackie strikes me as quite reverent toward its titular character and the singular situation she finds herself in.

Ah. I see. This is interesting, what you’re saying. But it’s different for me. If you look at my previous movies, you’ll notice that all of them are focused on male characters. With this one I have to contend with, not just a woman, but Jackie Kennedy! A former First Lady! I had to find a different path. I needed to find a new way to look at her. I’m not American. I would never have American patriotism. I only have patriotism for my country, my people. I regard the American flag the same way I regard the flag from China or France.

Does this make you less inclined to dissect the image of Jackie?

I don’t intend to divorce myself from politics because I don’t believe this is possible. I would simply say that I looked at her through a lens of love and compassion. I had this idea of Jackie Kennedy as an American queen. I was a novice. Then I went to YouTube looking for material and found the White House tour Jackie did in 1961. I couldn’t believe what I was watching. When she came to the White House she did a restoration for which she was heavily criticized. People said she did it with public money, which wasn’t true. People said she did it just to match her own taste, which was partly true. She hired a team who went all over the United States and brought back furniture that had originally been in the White House. She wanted to protect the legacy of that building. JFK suggested she put together this TV show to show the people what she did and why. I had this idea about this superficial woman who was mainly concerned with fabrics and fashion, but in this show I found the woman who captured my imagination. I was so moved by the way she would express herself, try to smile. I found out that she wrote the script, that everything she said was her own words. I saw the notes from her interview with Arthur Schlesinger and began to sense how political she was. Believe me, man, if I’ve done anything in my life it’s study political people, and there are very few with such a powerful sense of politics.

This idea of trying to control a legacy connects Jackie to Neruda and No, where we find the Pinochet regime struggling to portray itself as benevolent.

This legacy thing interests me. Maybe it always will. But if there’s a bridge that could connect all my movies it’s the idea of people that are victims of historical circumstance, people forced to behave in ways they don’t fully understand, who don’t know exactly what it is that they’re doing or why.

Neruda

In Tony Manero it seems like the historical circumstances are facilitating or permitting sociopathic behavior in your protagonist that might otherwise have never manifested. It made me think of certain Pinochet-era narratives from Roberto Bolaño, such as his novels Distant Star or By Night in Chile.

Absolutely. It is a kind of license. The same is true with Post Mortem. These are people whose lives might have been unremarkable if it weren’t for history tapping them on the shoulder and offering another path. But with Jackie and Neruda we shift the focus away from individuals on the periphery of history and onto people who are right at the center.

Watching Neruda reminds us that there was a time when writers and artists actually held a profound influence. At least enough influence to be considered a threat to the establishment.

I know. It’s strange to think of it. Neruda’s particular power came from how he was able to describe our country, our society, our people in a way that no historian or journalist has ever done. If you want to understand who we really are, read Neruda. Neruda is in our water. He’s everywhere. That’s why instead of dealing with his poetry we chose to absorb the poetry and see what comes out after. Neruda is what transpires after drinking that Neruda water.

Yet I don’t think the literary precedents for the film’s story lie in Neruda but, rather, in the work of other Latin American authors.

You know Jorge Luis Borges?

You took the words out of my mouth. The detective’s journey feels Borgesian.

Borges had an idea of overlapping fictions. Neruda is a Nerudean story overlapping with a Borgesian process. Well-known people throughout history at some point become concerned with managing their own legacy or iconography. I guess this is what you were getting at before, right? People want to project a certain idea of themselves, to twist history so that it regards them in a specific way. I’m trying to see how such people go about their business. Let’s go into the kitchen. Let’s watch the chef at work. Everything that happens in those five days for Jackie or those two years for Neruda is recorded. We know where they were at such and such time. But once they close the door, that’s where the fiction starts, the imagination starts. We make a little hole in the door, we slip a camera through that hole, we find out what we can see. I’m a storyteller. I don’t want to relay facts. I want to play. And to create a problem.

Put this way, Óscar is the problem. He’s unexpectedly cast in Neruda’s immense shadow and realizes that there might be a place for him in the mythology.

We all want to be in the story. “Say my name!” This is where Borges comes in. Óscar is a character written by Neruda. Neruda was very smart because he didn’t write only nice things about himself. He understood that if you can see the worst in yourself and use it, if you can make fun of and be cruel to yourself and find at some point that the nice character and the worst character are a single character, then you have something.

Do you see your films as being personal in that sense, as a way to explore darker parts of yourself?

You wouldn’t believe how fast it happens. You’re telling a story that has nothing to do with you, and then suddenly it gets down into something extremely personal.

Jackie

I ask because there’s a deep perversity at the heart of your films.

If there’s no perversion, there’s no beauty. Forget it. The word perversion comes from Latin. It means to see the reverse. Per-version: a different version of the story. It doesn’t necessarily refer to the actions of what we typically call a perverted, evil person. A bad priest, say. Or Donald Trump. It’s an oblique way to understand reality. And it becomes personal. Cinema is personal, man. The filmmakers that you or I admire were very personal.

Though it’s often most interesting when what’s personal in the work isn’t obvious.

That’s true. It’s almost always about desire. It’s your desire that can’t help but find its way to the screen. I deal with some very mean characters doing mean things, but I look at them with compassion. I love them. I love the meanest person I’ve dealt with. That’s the reason why I would never be able to make a movie about Pinochet: there’s just no way that I could find anything there to love. So I wonder how [Paolo] Sorrentino is going to do the Berlusconi movie. I’m dying to see that. How do you do that? I don’t know. But it’s cinema. Let’s all of us keep letting cinema find its way. Can you imagine this planet without cinema? I can imagine it without phones. Without Internet also. But without cinema? I don’t know. I would probably be a lawyer.

This article originally featured an inaccurate statement regarding Larraín’s father based on erroneous sources and has since been modified.

Closer Look: Jackie opens on December 2 and Neruda opens on December 16.

José Teodoro is a critic and playwright. He is a contributor to Film Comment, Cinema Scope, The Globe and Mail, The National Post and Brick.