By Henry K. Miller in the July-August 2006 Issue

Notes from Underground: Peter Whitehead

In the right place at the right time, documentary filmmaker Peter Whitehead wrestled with the contradictions of the ’60s counterculture—and embodied them as well

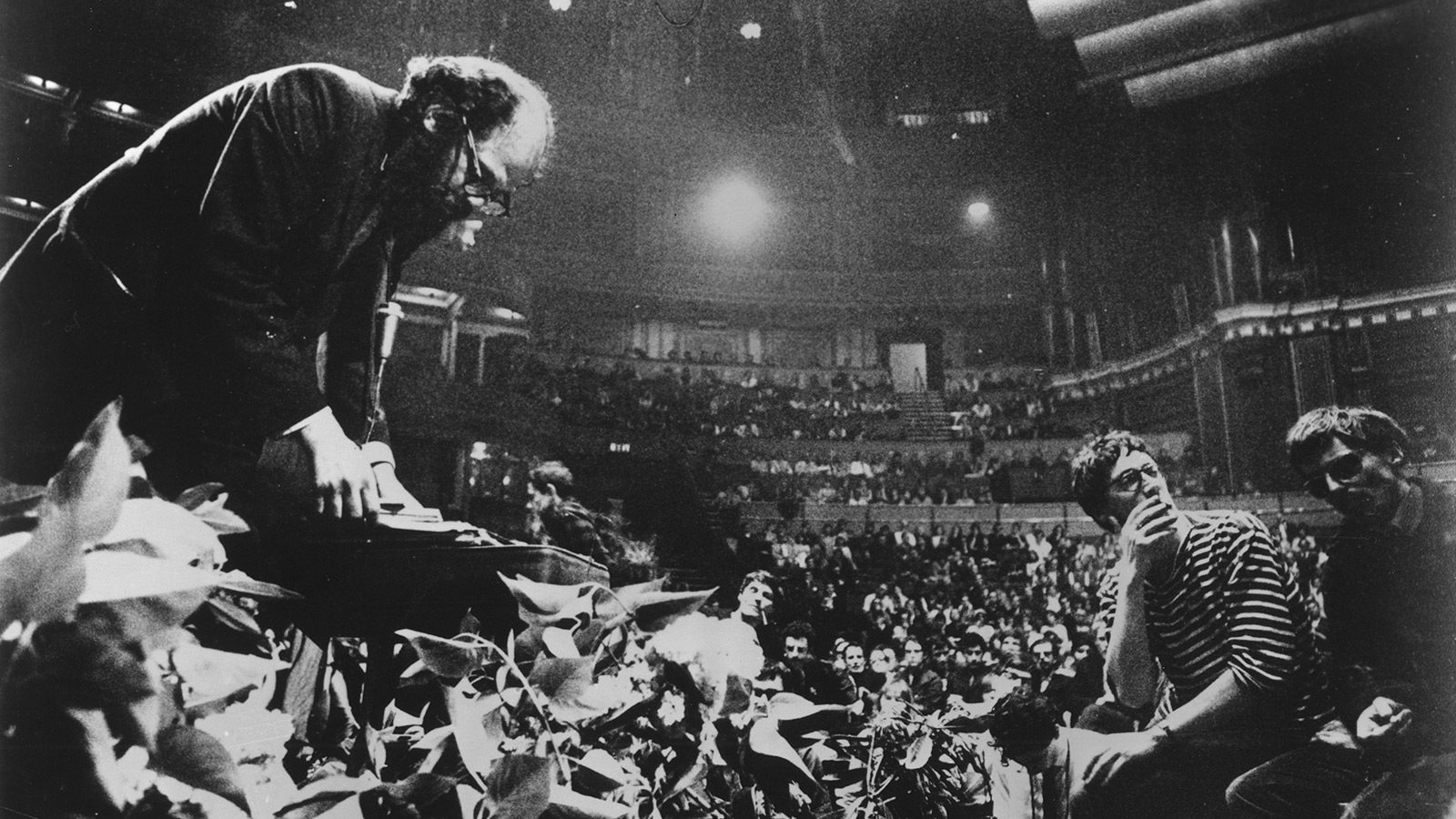

In D. A. Pennebaker’s 1965 film Dont Look Back, shot during Bob Dylan’s spring 1965 tour of England, the singer asks a hanger-on: “Are there any poets like Allen Ginsberg around, man?” “No, nothing like that.” Ginsberg himself joined the tour in London, where Dylan had sold out the stately Albert Hall. A few weeks later, with Dylan on the road again, the poet tracked down his English acolytes to Better Books, the capital’s conduit for San Franciscan literature and Parisian film journals. After his reading, the crazy idea got about: if Dylan could do it, why not Ginsberg and the other beat superstars? His companion, New York filmmaker Barbara Rubin, booked Albert Hall, but the event, eventually known as the International Poetry Incarnation, was hijacked by a posse of native poets who appended a roster of complete unknowns to the big-name bill. Rubin planned to film the event, but her experimental double-exposure technique was deemed unlikely to preserve the poems as read; Rubin was ousted in favor of Peter Whitehead, a young man from the Better Books crowd who was then employed as a news cameraman. Against all odds, the place was packed.

From the July-August 2006 Issue

Also in this issue

Whitehead had first picked up a camera while enrolled as a painter at the Slade School of Fine Art, home to Britain’s first university film department, then presided over by Thorold Dickinson, a veteran director whose commitment to film art stretched back to the heroic age of Soviet cinema. Whitehead carried his painterly admiration for Francis Bacon, whose work oscillated between representation and abstraction, into his student films. If not reaching Rubin’s levels of abstraction, Wholly Communion (1965), as the Incarnation film was eventually titled, would cause him to “abandon any pretensions [he] had as a cameraman about the objectivity of film,” improvising a personal cinematic brushwork of zooms and whip-pans. The film debuted in London in the same program as fellow Slade graduate Marco Bellocchio’s Fists in the Pocket. Film critic Raymond Durgnat—yet another Slade alumnus and Better Books regular—wrote that it “penetrates, through the ‘event,’ to feelings and hopes.” With 45 minutes’ worth of stock to cover a four-hour reading, Whitehead was “editing the event as it happened, before it happened,” responding “psychologically and intuitively” to the poems that engaged him as they unfolded. Among these were Harry Fainlight’s bad-trip epic “The Spider,” and Adrian Mitchell’s “To Whom It May Concern,” addressed to those “unhappy murderers in Mekong.” Both were early markers of what would be the two great political causes of the emerging scene: hallucinogens and Vietnam.

The Incarnation was the breakout moment for a hitherto disparate underground. On the reputation of Wholly Communion, Whitehead was invited to film the Rolling Stones, who’d just had their first transatlantic number-one hit, on tour in Ireland in September 1965. From this point on, his biography reads a little like the lyrics for “Sympathy for the Devil,” a string of assignations with key figures at key points in the history of the counterculture. But despite the apparent ease with which he found himself moving and shaking in the right places at the right times, much of the strength of his work derives from the uneasy relationship between his present-tense hipsterdom and a submerged past emblematic of England’s default wretchedness.

Born in working-class Liverpool in 1937, Whitehead had been educated away at boarding school. Since the mid-19th century the public school system had provided the means by which the sons of the British aristocracy and bourgeoisie alike could be socialized, in Perry Anderson’s words, “in a distinctive, uniform pattern, which henceforth became the fetishized criterion of the ‘gentleman.’” The postwar Labour government’s reforms allowed for the assimilation into this bloc of a small number of the brightest working-class children via scholarships—an amazing opportunity, to be sure, but one that was always lived ambivalently. Perhaps most prominent in British television in its ’60s and ’70s prime, the “scholarship boy” became a pivotal figure in the British intelligentsia’s left-wing inflection. By taking up the theater at Cambridge (on another scholarship), Whitehead was on a path comparable to that of Ken Loach, who was over in Oxford around the same time and soon to become one of the BBC’s golden boys. His education gained him the deregionalized posh accent, which, with that famously infuriating self-confidence in person and prose, is the ineradicable passe-partout of the public-school-educated Englishman. Still, the price was high. Uprooted in adolescence, he was unavoidably alienated from his cultural heritage.

His decision to take up the easel after three years studying physics marked him out as different, but in ’60s London, or at least within the milieu that made it swing, it was absolutely the done thing to affect a proletarian accent and keep up, in a suitably laid-back way, with pop culture—everything that Whitehead had had the mutable privilege of being educated not to do. When Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham made the call, a convoluted class history lay behind the fact that Whitehead knew England’s newest hitmakers chiefly as the guys who’d been caught pissing in front of a gas station.

The pissing incident was part of a larger narrative. The Stones, like most of the hard-riffing R&B enthusiasts that comprised the British Invasion, had backgrounds in art colleges less prestigious than the Slade in London’s outer boroughs, and if the last thing anyone seemed to do there was paint, the situation allowed high-art ideas to infuse the music scene. While The Who and The Creation climaxed their shows with works of “auto-destructive art,” the Stones were a kind of adventure in packaging on the part of the controversy-seeking Oldham, who set out to make his predominantly lower-middle-class charges appear the epitome of dangerous, proletarian youth—the anti-Beatles—a ruse so blatant it had to be Pop Art. The Whitehead film Charlie Is My Darling (1966) was commissioned to attract financing for a Stones feature vehicle, and Oldham wanted the group in character both onstage and off.

Charlie Is My Darling – Ireland 1965 (Peter Whitehead and Michael Gochanour, 1966/2012)

If Dont Look Back is a classic example of non-interventionist Direct Cinema, Charlie Is My Darling is cinema vérité, never pretending that the camera and its operator should or could be invisible. As in Wholly Communion, Whitehead would be a participant-observer, approaching the Stones as an outsider with inside access. Neither myth-making nor debunking, Charlie interrogates the relationship between the Stones’ scrupulously constructed bad-boy image and their “real” selves without coming to easy conclusions. At the start of the film, over concert footage of the band’s notorious singer in audience-taunting form, we hear an earnest young Englishman: “I don’t really know what I am on stage . . . You’re acting—it’s not really you.” Yet as we cut to Mick Jagger continuing his answer, it’s hard to avoid Oldham’s conclusion: Jagger is far less convincing as this self-deprecating and thoughtful interviewee than as the long-haired monster of tabloid legend. Even if the latter is all front, it’s real enough for the kids who, in the film’s most incendiary moment, storm the stage and chase the band into the streets, with the camera caught in the middle. One of Whitehead’s friends has recalled, “Peter was very quick to tell me he was working class—otherwise I’d never have guessed,” and in Charlie his interviewer’s voice never once loses its public-school sharpness. In the context of the ’60s demimonde his decision not to claim his salt-of-the-earth credentials was almost perverse. Jagger meanwhile would never again let his guard down to the same extent, soon adopting an extraordinary Cockney drawl to close the gap between his stage and “real-life” personas.

Owing to rights issues, Charlie is samizdat cinema but has nonetheless proved influential. Antonioni saw a cut—in Whitehead’s Soho flat—before shooting the famous scene in Blow-Up in which The Yardbirds’ Jeff Beck trashes his guitar, provoking a small riot. For Whitehead, the film was the beginning of a brief career as perhaps the only forerunner to the music-video auteur. As well as making promotional shorts for the debut singles of Nico (before she joined the Velvet Underground) and Jimi Hendrix, he shot numerous clips for the Stones, all screened on the BBC until they declined his spot for 1967’s “We Love You,” which explicitly linked the band’s tangles with the law after a drug bust to the trial of Oscar Wilde.

Pitched somewhere between documentary and filmed theater, The Benefit of the Doubt (1967) is concerned, like Charlie, with role-playing and the performer-spectator relationship. Interspersing scenes from US, the Royal Shakespeare Company’s ambiguously titled 1966 attempt to address the Vietnam War on the West End stage, with interviews with the actors and writers behind it, the film anticipates the turn in the European New Wave—Rivette, Straub, Bertolucci—toward political theater. The play’s Brechtian first act combined didactic sketches, documentary reconstructions, and satirical songs; the second, moving further into Artaud territory, was given over to self-criticism, concluding with a frighteningly intense speech accusing the audience and cast of bad faith and passivity. Whitehead’s film cuts to this monologue from an interview, shot in black-and-white, with the actor who performed it and who declares herself “suspicious and critical” of the whole enterprise, and then runs her speech over color documentary footage of a demonstration outside the U.S. embassy. The color-coded transition at once suggests political activism as theater—as in Bertolucci’s Partner—and admits the theater’s powerlessness.

Like his hero Jean-Luc Godard, whose scripts he translated and published, Whitehead was drawn to the antiwar movement but distrusted the simple deployment of the tools of narrative filmmaking, not to mention the truth claims of documentary, to political ends. Two projects Whitehead had worked on with the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation—a collaboration with lawyer Mark Lane on a script about the Kennedy assassination and cover-up (shades of Made in USA) and the editing of North Vietnamese propaganda films—fell apart under the weight of these contradictions.

Reviewing Godard’s Pierrot le fou in mid-1966 for Films and Filming, Whitehead wrote: “There is no longer a continuous, flowing, narrative reality, for anyone anywhere; it must be a collage of signs, images, instants, quanta of perception and emotion and thought.” He wasn’t just talking about movies. Over the course of that year the more switched-on art-school musicians started to play—and dress—very strangely, the live sound of the underground modulating from Yardbirdsy “rave-up” to psychedelic “freak-out.” A painter Whitehead had known in Cambridge was now leader, under the name Syd Barrett, of the Pink Floyd Sound, house band of the now-legendary underground nightclub UFO, where they played to an accompaniment of trippy projections and avant-garde films. Whitehead put the Floyd into a studio to record their signature track, the epic instrumental “Interstellar Overdrive,” for the soundtrack of his next film.

Taking its title from Ginsberg, Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London (1967) pushed vérité into new shapes. Shot on the streets and in the clubs, the film makes extensive use of freeze-frames and other editing devices that bring to mind the spacey production techniques of psychedelic pop. A documentary on a semi-imaginary phenomenon, Tonite is torn between Whitehead’s need to celebrate the extraordinary cultural explosion going on around him and his desire to unravel the media mythologizing—a task made complex by the heterogeneity of what had been lumped together (in what he now regards as the work of CIA black ops!) as “Swinging London” in Time’s spring 1966 cover story.

Tonite Let’s All Make Love In London (Peter Whitehead, 1967)

The great novelty of the English underground in the two years following the Incarnation had been the extent of its integration with the pop mainstream, but the two were never identical, and Tonite reflects this brief period of confused symbiosis. Within a few months of Whitehead recording them, the Floyd were in the charts and cutting an album down the corridor from the Beatles, who had themselves been absorbing the contemporary avant-garde via Paul McCartney’s underground connection, Better Books honcho Barry Miles. But by 1967’s “Summer of Love,” when the underground—West Coast and London—went global, that dynamic relationship, in which Whitehead was a key intermediary, was breaking down.

“Underground” had become what the critic Frank Kogan calls a “Superword,” “a battleground, a weapon, a red cape, a prize, a flag in a bloody game of Capture the Flag . . . The fight is over who gets to wear the word proudly, who gets the word affixed to himself against his will.” If the underground’s pet musicians were visibly taking over the mainstream, underground movies were on a diametrically opposed trajectory. The London Film-makers Co-op, founded in Better Books’ basement with some involvement from Whitehead and Miles in 1966, would eventually refuse the “underground” badge and any danger of crossing over, adopting nonrepresentational “structural” film as a correspondingly ascetic aesthetic; by contrast, Co-op refugee Durgnat found in Tonite passages of “abstract cinema which has learned from light-shows how to have a thick, sensuous impact on its audience.”

Still, the film made clear that the party was almost over. Among the interviewees, David Hockney, who would seem to represent all that Swinging London was meant to be about—social mobility, creativity, international recognition—is both the most entertaining and the most blunt, spending most of his time boosting New York and Los Angeles and lamenting England’s puritanical drink licensing laws. Whether it was the pop artists’ affection for Madison Avenue sheen or the beatniks’ passion for everything that stood against it, the cinephiles’ connoisseurship of postwar Hollywood or the art-college musicians’ reverence for obscure Chicago bluesmen, ’60s London was collectively fascinated by American culture, and Whitehead’s transatlantic hop to present Benefit and Tonite at the 1967 New York Film Festival represented a chance to find the main nerve.

Commissioned to give the New York “protest art” scene the Whitehead treatment, the director found himself experiencing the conflicts that had structured his British films in even sharper form. As the antiwar movement—mounted on a scale never seen in Britain—gained momentum, both the film and the scene it was covering looked increasingly marginal to real political change. At the start of Benefit, RSC director Peter Brook tells a press conference that the chances of the play influencing political decision-makers in London and Washington are “absolutely nil.” With thousands out demonstrating, what use was another movie? At first Whitehead followed through the implications of Benefit’s final sequence, and, back in Europe, attempted to fictionalize his predicament. Picking up some threads from the Kennedy scenario, he developed a script about a filmmaker’s transition from protest to revolutionary action—in this case, political assassination.

The day after Whitehead, script and financing in hand, returned to the States in March 1968, Martin Luther King was assassinated. At that point the fiction project went the same way as the documentary; long obsessed by the responsibility of the filmmaker to the events he observed, Whitehead felt somehow implicated in murder. After a month’s brooding, punctuated by some desultory shooting around the aftermath of the Newark riots, he joined the student occupation at Columbia University. For the first time since his arrival in the U.S. half a year earlier, Whitehead was able to participate in—commune with—what he was filming, but although he left the country with extraordinary footage, including the bloody end of the occupation, he didn’t have a film. What became known as The Fall (1969) was edited over the next six months. It would be a narrative of sorts, telling the story of Whitehead’s personal and political crisis of representation, and its tentative resolution. Today he says, “I put myself together by putting the film together.”

His time in the States gave him a very different take on the événements of May ’68 from his continental peers, many of whom interpreted them as a “performance” on the part of the student vanguard, intended to “wake up” the rest of the population. The scale of the riots and demonstrations in the U.S., and the enormity of the assassinations, took Whitehead beyond this position, which had found its way into his unfilmed script. He’d witnessed state violence at Columbia and suspected its complicity in the murders of Dr. King and Robert F. Kennedy; the problem was bigger than any spectacle. After completing The Fall he went dark—for a few years, at least. The logic of the film pointed to direct engagement with the world. Reviewing Godard’s Weekend, another film that proclaims its own insignificance, around the time of The Fall’s completion, he declared: “The Promethean Fire of Revolution is in our blood whether we are conscious of it or not.”

The Benefit of the Doubt (Peter Whitehead, 1967)

While Whitehead was editing The Fall, Godard had hooked up with Pennebaker and Leacock to film One P.M. (aka One American Movie), a travelogue of the Left in the wake of the Chicago Democratic Convention meltdown. The French filmmaker walked away from the movie and from America, the abortive project marking his own final break with the established cinema. Both directors were in a sense overawed by America, but Whitehead had eventually returned to his footage. If Godard attempted in his Dziga-Vertov films to make a critique of the image as truth with a theory of the word, an analogue of whose structures was held to underpin the dominant forms of cinema, Whitehead invoked a preverbal—and thus prelapsarian—form of communication via the image alone, which he at once acknowledged as unattainable. The Fall is his unfolding of this process of realization, and if it led to his temporary abandonment of the cinema, in making it he found a point of equilibrium: “What you see on the screen isn’t real; you must remember it’s film you’re looking at. But once over that mental adjustment, film can be the medium by which we could regain contact with the world.”

“For a few years…” In the grand scheme of Whitehead’s life, filmmaking was just one of many careers, and one that assumes undue prominence because his film archive, endlessly drawn on by television companies, has proved an important revenue stream. By his own account—or by one of his accounts, anyway—he gave up filmmaking for good on the day of The Fall’s debut in 1969, when, having heard that the film’s chances of distribution outside London were slim, he encountered a falconer in an Edinburgh park. The bird’s place in Egyptian mythology had fascinated him since his early twenties, and falconry, to his mind, suggested a way of making direct contact with the world after years behind a camera. Though Whitehead was not alone in his yen for Egyptology—around that time Kenneth Anger filmed a version of the Horus myth with Stones associate Donald Cammell—he went deeper into it, and ultimately became a full-time falconer. He did not, in fact, give up filmmaking—a bare six months later, he was shooting a Led Zeppelin concert—but it was no longer his main business, and he’s subsequently disowned, if not withdrawn, all of his ’70s work.

The Fall was eventually taken up by The Other Cinema, one of numerous attempts at creating a “parallel” culture in London in the wake of the underground’s peak period of turbulence, but in truth Whitehead had flown the underground coop when he took off for the States. (“There seemed nothing more to film in London except my boredom, despair, and apathy.”) For the beautiful people, and especially the rock aristocracy, to which only semi-metaphorical rank Whitehead’s musical collaborators had been elevated, the turn of the decade occasioned a remarkable diaspora—to California, to North Africa, to England’s West Country, to the spiritual East, and, in the case of the Stones, to tax exile in the south of France. It was from this last sanctuary that Whitehead emerged in 1973 with the introspective Daddy, a taboo-busting and more or less disastrous collaboration with the sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle.

In 1977 he resurfaced with Fire in the Water, a “requiem for the ’60s” that intercuts highlights from the Whitehead repertoire with interludes, shot in a remote corner of Scotland, that attempt to dramatize his renunciation of the cinema. “We must destroy once and for all the image that we cling to of a golden age in which everything was possible. The revolution, in time, like all past times, must return”—Whitehead’s narration was ironically unaware that the revolution, or at least a countercultural blast equal to the previous decade’s, had returned in his absence in the form of punk. Aesthetic severity was the order of the day—note Johnny Rotten’s “I Hate Pink Floyd” T-shirt—and any film featuring tracks from Dark Side of the Moon seemed out of touch with the London scene that Whitehead’s best work had been steeped in. A somewhat less successful expression of creative impasse than The Fall, Fire was Whitehead’s last film—this time for real.

A few years later he took the post of falconer to a Saudi prince, abandoning Britain for the duration of the ’80s and returning during the first Gulf War. After a decade that saw the Thatcher government reverse most of the political and social gains of the postwar era, and make the cultural legacy of the ’60s a toxic ideological battleground, the belief that the moments captured in Whitehead’s films represented a golden age had its main constituency among music fans. His most financially successful work has turned out to be an “instrumental” re-edit of material from Tonite and previously unseen footage of the Floyd at UFO, released on video in 1994 and subsequently on DVD. He began to self-publish novels to set the record straight: about the disintegration of the underground, about the corruption of the culture industry (publishing included), and, up to a point, about himself.

If the Whitehead revival of the last decade has taken place on the margins of official film culture and the academy, it’s partly because his work evokes tensions from the past that seem comfortably absorbed in the present. The transmission of The Falconer, Chris Petit and Iain Sinclair’s quasi-biographical 1998 television essay, saw Whitehead engaged in a “bloody game of Capture the Flag” with the very people who seemed to be championing his rediscovery—so often a placid affair of retrospectives and respectful profiles. Much was at stake in the encounter: Sinclair, poet and psychogeographer of subterranean London, and Petit, film editor of Time Out when the magazine, per Sinclair, “still had a patina of credibility,” represented the underground Whitehead had left behind at the end of the ’60s, and which had rumbled on in a kind of half-bohemian, half-academic internal exile ever since.

Sinclair—as much of a mythomaniac as Whitehead himself—cast his quarry as a working-class boy “who decided to fuck the system from the inside,” continuing the culture wars of the ’60s by other means. “He made the film about my outwardness, my worldliness, my life-on-the-fringes,” Whitehead complained. “It was about the Mask, the Persona, the false side that I have shown to the world.” But Whitehead isn’t out to print the legend—he’ll readily recount his abandonment of the camera and discuss the films he actually went on to make—so much as put off its conclusion. He’s fond of telling interviewers, “All this is a façade, but if you do a good job on this I’ll tell you the real story.” There’s always the promise of another Mask beneath this one. Part shaggy-dog story, part mystical odyssey, Whitehead’s autobiography—a multilayered project that takes in his novels, websites, and occasional media interventions—tells much the same story as his best films: keep on looking.

Henry K. Miller is a contributor to the magazines Vertigo and Plan B. He lives in London.