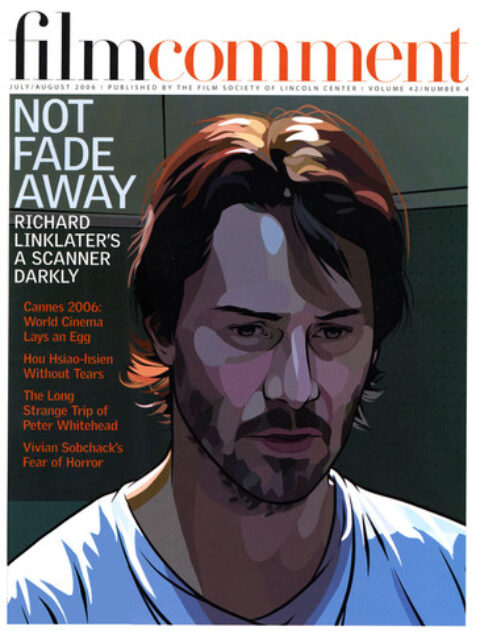

By Gavin Smith in the July-August 2006 Issue

Lost in America: Richard Linklater

A Scanner Darkly and Fast Food Nation present two sides of the director’s take on the American nightmare

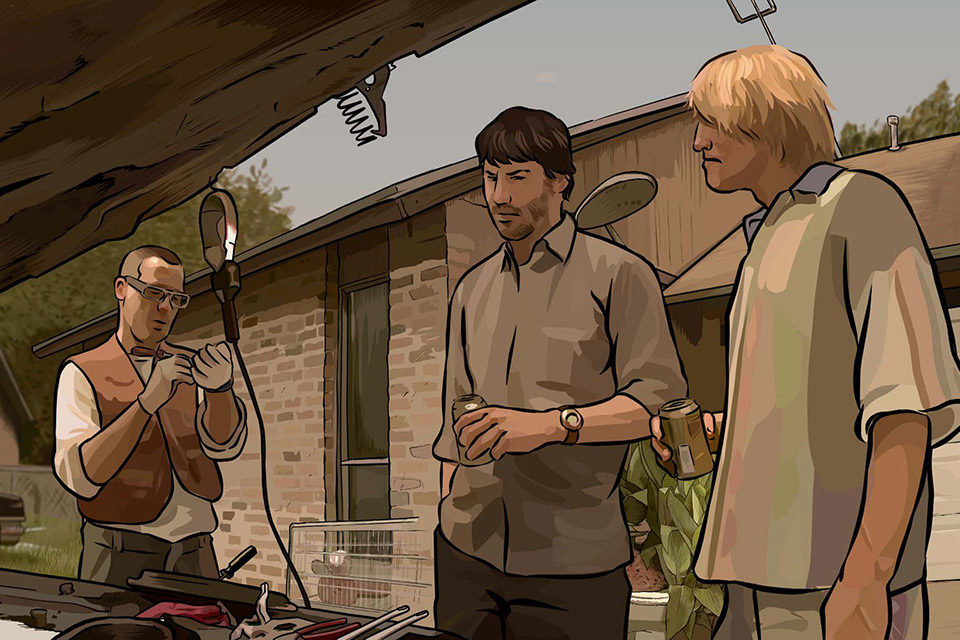

An extremely faithful adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s 1977 novel, right down to the inclusion of the author’s postscript roll-call of drug- casualty comrades, A Scanner Darkly finds Richard Linklater journeying deep into the spooky, lonesome badlands of the psyche. If the similarly animated and interiorized Waking Life (01) was a playful, free-associative exploration of dream logic and an engagingly dialectical survey of the nature of reality and existence, A Scanner Darkly is a bad trip in which the dissolution of a schizoid, drug-addled mind refracts a dystopian American Now. By the end of this tale of paranoia and betrayal, set in a spectral world where there’s a surveillance camera on every street corner, the film’s protagonist, Bob, a near-future undercover narc played by Keanu Reeves, has lost both himself and all but the most tenuous of connections to reality—and whether he’ll ever recover remains an open question.

From the July-August 2006 Issue

Also in this issue

You could say that Linklater’s a long way from home with this fitfully comic but ultimately bleak and haunting material. But is he? Most of his films are above all attuned to the way consciousness wrestles with questions of authenticity and self-definition—they’re driven by the intrinsic sense of possibility contained in people’s ruminations and open-hearted yearnings, in the human urge to question and inquire and connect. Despite its melancholic conclusion, Waking Life positively rejoices in the endless permutations of the mind’s engagement with the world, much as Slacker (91) celebrates the overwhelming diversity of individuality to be found if you spend a day wandering the streets of Austin, Texas, Linklater’s base of operations. And Before Sunrise (95) and Before Sunset (04) are two different takes on restless spirits trying on possible approaches to the world around them and coming to grips with life’s Big Questions, hopefully and self-consciously in the first film, and with regrets and doubts in its nine-years-on sequel. Linklater’s movies are grounded in a faith in the freethinking individual’s ability to find his or her own way instead of simply accepting received imperatives. At the same time, as Before Sunset demonstrates, introspection is no walk in the park; loss and disillusionment are never far. A Scanner Darkly, like Linklater’s 2001 digital video experiment Tape, plays out these same fundamental questions, but in a fallen world where life has been hollowed out and the future looks less than bright: “Does a scanner see clearly or darkly? I see only murk,” concludes Bob. Entropy and impasse, evident from the start in some of Slacker’s more nihilistic and paranoid monologues, have become this film’s domain.

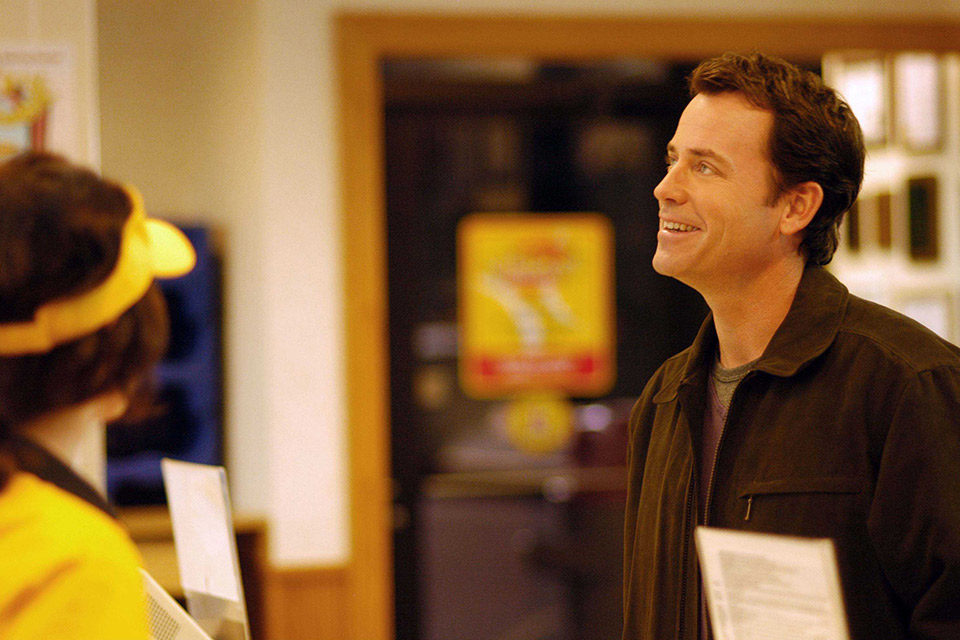

Back in the day, Slacker was described as a film that posited “personal refusal instead of politics.” Maybe. But as if to refute this, hard on the heels of A Scanner Darkly comes Linklater’s soon-to-be-released Fast Food Nation, with its grim minimum-wage realities and pervasive moral compromises. A Active take on Eric Schlosser’s nonfiction expose, it presents a holistic view of the inner workings of a corporation that is McDonald’s in all but name. Matter-of-fact and unsensationalized but no less incisive for it, the film delves into the business of junk food from top to bottom, dividing its time among three narratives that depict working life in the meatpacking plant, in retail outlets, and in the executive suite. Laying bare a structure that effectively embodies an entire socioeconomic system and its values (“the machine that’s taken over our country,” as one character puts it), Fast Food Nation is Linklater’s most ambitious film to date in its reach and scope. Here, for once, questions of identity and the meaning of life must take a backseat to putting food on the table and making a living.

Linklater’s films have always been, in part, an implicit ongoing reflection on American life and values, from Dazed and Confused (93) to School of Rock (03). Taken together, Fast Food Nation and A Scanner Darkly constitute a comprehensive political vision of today’s gloves-off, No More Mr. Nice Guy America, where dissent isn’t tolerated and exploitation is the name of the game.

Fast Food Nation

There’s a couple of scenes featuring Ethan Hawke as the young girl’s uncle in Fast Food Nation that are very much a restatement of the Slacker ethos of nonconformism and doing things your own way. And that’s pretty much the ethical cornerstone of your films in general. Did you ever feel Slacker was an albatross around your neck?

Yeah, there’s a certain ethos, I guess. Clearly there’s a line that runs through there, and that’s probably not going to go away. I never really saw it as an albatross. It’s kind of a blessing and a curse. It was sort of my calling-card announcement, like, “Here’s what I’m about,” to some degree. So it sort of sets a tone. I’m proud of that. When I did Waking Life, I was like, “Yeah, this is the same guy who did Slacker.” It’s the way my brain works, I guess. This is how I feel about the world. I’m looking for a new way to tell a story, I’m looking for a way to cram in a bunch of ideas that don’t necessarily fit into a movie—without even being that conscious of it back then. The more movies you make, the less pressure there is on any one film. The trouble when you only have a few films is those films define you completely. I mean, yeah, this is a vibe of who I am, but how many films would you really have to make to express yourself completely? I don’t think you ever could. So for me it’s about just carving off little pieces of myself here and there. A lot of stories I really want to tell would flip everyone out—on the surface they wouldn’t seem like movies I should make. But just by the nature of having made a lot of movies now, I think people give you the leeway. When I was “the guy who did Slacker, that was all about pop culture”—which it really isn’t—they’re putting you in a certain place. And they want you to stay in that place, just because it makes categorical sense. And when you jump out, you’re not being consistent, and it’s judged as being not worthwhile. I’ve felt that on other films I did, that everyone said, “No, we don’t want you to make that kind of film.” For me, it was probably The Newton Boys. As personal a film as I’ve made actually and one that I’m really happy with, I really put everything I had into it. But the vibe at that time was, “Wow, no! You don’t get to make that kind of movie.” I think if I did that same movie today, post-School of Rock, it would have been seen in a different way.

Do you have projects that would seem like a big stretch for people, as they understand you now?

I have some, but I don’t think in those terms. Some of the films I have don’t feel like a big stretch for anybody. I remember way back when, there was a review of Slacker where the guy wrote, “There’s no film like it, but the question is: Should there be?” I was like, “I like that.” So, yeah, I’ve got some crazy films I want to do. I think the question won’t be so much me wanting to do it. It’s more like, “Do I really want to see a film about that.” So that’s my challenge. Just to try to make movies that make people go, “Who would even think to make that movie?”

The Ethan Hawke speech in Fast Food Nation is also about options that aren’t really available to most of the characters in the film.

Yeah, the characters in the film are far from being a loose person in your twenties with no attachments. Those are the characters in Before Sunrise or Slacker, who seemingly aren’t so embedded. And I love that. I think that’s the most important phase in anyone’s life, those years they can get where they really aren’t attached—if they can get any years at all. Some people never get it—college, job, marriage. You know, you never got that second to really think about things, maybe discover who you are outside of all those external forces that are acting on you. I have a lot of sympathy for people in their twenties or thirties or even forties who are still finding themselves and open to change and redefining their own relation to the world. But it’s obvious that once you have kids and a family and you want to be a responsible person, it cuts out a lot of possibilities in your life. So if you’re really struggling just to survive—talk about cutting off possibilities. I read something about happiness that defined it as being beyond just abject poverty. If you can get up just a little bit beyond that, then money and all the material things really don’t make a big difference. But you have to get beyond that first level of deprivation, which so many people are at.

You did an HBO pilot called $5.15/Hr. which was described as “a workplace comedy,” but HBO didn’t pick it up because they found it sad and depressing.

My whole life I’ve always wanted to depict people who just work. The joy and misery of work. I had a lot of shitty jobs growing up—I was an offshore oil-worker. It’s for an audience who’ve never really worked like that, who can’t imagine doing that and being anything short of miserable—you know, like the people who run things like HBO. But they think, “Oh no, people don’t want to see people working.” But there is a history, certainly in Great Britain, of the workplace comedy. You would think in a tribal sense that that would be important. Definitely Hollywood doesn’t want to make films about that, but I got suckered into thinking, “Oh, well, TV might be the right place.” It was tough to do a pilot, because it has to work on its own, but it has to hint at future events. So it’s a restrictive little genre. It’s all character-based stuff. You don’t have to tell a huge story every episode. So I tried, and I was happy with it. But when they chose not to do it, I put all my feelings of that into Fast Food Nation.

Fast Food Nation

What sort of workplace?

The first episode was mainly around a restaurant. But it was going to be a hotel. It was an ensemble, and a lot of the characters had multiple jobs. They needed more than one job. So a lot of it was about quitting, getting fired, and getting hired and retrained at other places. You’re doing the rounds. You’re going to another place. The jobs are remarkably similar. The way you’re treated is very much the same.

Did you ever see Chris Smith’s American Job?

Oh, I love that. About the time I was finishing Slacker, I tried to get the rights to Charles Bukowski’s Factotum, where he’s just doing shit work. He was just going from job to job to job.

Why is it that your movies are so verbally driven? Almost all of them are built around conversation and speech. Do you see language and verbal expression as the place where we really see who people are?

Well, I always thought so. If you look at the world around you, we define ourselves more by speech. I remember Sam Fuller saying, “You don’t talk about things. You show it.” And I said, “He’s right. That is cinema.” But when I turned on the camera, it really was about people talking. That was the world I had experienced. I hadn’t been to a war. I hadn’t been a crime reporter. I was always intrigued by what people said, what that meant about what they were saying, and what that betrayed about them—regardless of whether what they were saying made any sense or not. I had done that first film [It’s Impossible to Learn to Plough by Reading Books] that’s very much a kind of structural thing that was about a lack of communication. And in Slacker I wanted a world where the interior was brought forth—kind of like in theater. That’s just the way it came out once I really started to do stuff that felt personal to me. It was people just rapping, talking a lot, with not much going on, technically speaking. It wasn’t really conscious. I’m not that verbal. I’m more of an observer than a talker. So I was as surprised as anybody, really, that that’s how it came out.

But if Slacker is about externalizing interior monologues, by the time we get to Before Sunrise, I start to wonder to what extent language really is a conduit through which you get at somebody’s authentic self—it’s as if you’re taking everything they say at face value and there’s not much sense of subtext for the most part.

I was going for a sincere communication. I felt I had bounced around between no communication and an interior-monologue communication that arguably doesn’t stick or only communicates to a certain extent, maybe only makes sense later. I think I liked the idea, starting with Before Sunrise, of people who were trying to connect. It was about being understood. In Fast Food Nation, so many of the characters aren’t articulate about anything bigger than their immediate situation. Amber and the college kids have that ability to sit around a dorm room and question things and define themselves politically. That’s the role they’re playing, and they’re afforded that. And they’re middle class. They’re even encouraged to do that in the environment they’re in. That’s not an option for Raul, Sylvia, and Coco, because they’re poor and they’re coming from another country. There’s no time for that in their life.

Do you see any kind of connection between the kids in Fast Food Nation and the kids in SubUrbia? The sentiments expressed by the kids in SubUrbia seem more received and rhetorical.

Yeah, SubUrbia is darker than Dazed and Confused. The kids in Dazed and Confused are in high school, and it’s all in front of them. In SubUrbia they’ve all hit their first wall, whether it’s college or getting out of town. I was always amazed at the lack of sympathy for them—that sympathy drops off once you’re in your early twenties. People expect you to have it all together, and they’re on you to have a plan, and that’s when you need the most slack, I think. So technically they’re a little younger than the people in Slacker, but they’re at a similar place. They’re pre-Slacker actually in their own development—

If they get out of that town.

Yeah, if they can get out and go to a place that will put up with them, where they’ll find kindred spirits.

Slacker

The characters that you’re most hopeful about are the girl who wants to be a performance artist, and the Steve Zahn character, who’s going to go off and make a music video—go and do something.

[Laughter] Yeah, well, at least they have hope of getting out and finding some useful activity for themselves. You could also say they’re totally delusional and full of shit. But, what the hell, we all are at some point, if not always, in our lives. You have to be kind of delusional to step out and do anything.

Are you ever tempted to revisit the less verbal kind of cinema of your first film? Is there anything that you think about doing that would be more behavior-oriented than dialogue-oriented?

The handful of movies that I feel like I’m doing probably don’t go back there. I’ve stepped out a couple times, like The Newton Boys, I felt was the one time I got away from introspective characters. They were very active. It didn’t have a lot of subjectivity. It was all about acting. It was a very aggressive, outward approach. But what was leading them to that was the same ethos that a lot of the other characters in my films would have, that kind of disdain for authority.

More than half of your films employ some kind of structural device, usually related to time. I’m curious about where that impulse comes from, to set yourself a challenge or a limitation. It’s almost like it’s an exercise, but obviously, there’s a lot more at stake.

Yeah, I don’t really know. Isn’t there something kind of primordial about it? Go back to the Greeks where all the stories were in very limited time frames. I think it’s pretty old, that impulse to close in your narrative. But I don’t know why. It worked for me. Part of my thinking about film was always trying to get down to what I would call real time, carving out real time. I joked back then when people were going like, “Hey, all your films, they’re like 24 hours,” I always joked, “Oh, someday I’ll do a Winter Light–type of movie where it’s all real time.” I didn’t really have the story at that time, but then it just came to be that I’ve done that twice, with Tape and Before Sunset. I’ve done two actual real-time movies.

Not to read too much into it, but it kind of suggests that you’re struggling with the passage of time. That’s why I’m curious about this 12-minutes-a-year project. That seems like another way of getting at that.

I wanted to make a film about childhood, but I couldn’t figure out how—one little section, like The 400 Blows, or a couple days or a couple years, but then you have all the practical things about aging. So it hit me that I could just depict a life over numerous years and make it a much longer-term project with the prospect of the people getting older. You just jump on at one point and jump off at another, and a bunch of years will have gone by.

Is there a screenplay?

No, every year I think about it. I’m about to shoot another one—my fourth—coming up.

It’s with the same child?

Yup, same kid growing up. It’s all fictional. There’s nothing documentary about it. The rough outline is first through 12th grade, like the whole public school pre-college.

A Scanner Darkly

Theoretically you could just keep on making the movie forever.

[Laughter] We’ll have to see how it goes. Anything could happen. What makes it interesting is that you have to deal with a year of your life at that age, and then you have to deal with a year of your life at this age. You know, whatever’s going on in your practical world, and then I have to think about like, “OK, fourth grade, fourth grade, what’s going on there that will make an interesting?”

Is it something where you’re collaborating with the child?

Yeah, the child and everybody else in it, too. Because it’s not a period piece. I’m not actually making my childhood. I’m dealing with the real world. So it’s like, “Well, what computer games are you playing? What’s going on?” It’s very much about his parents too. It’s kind of seen through his eyes, but the parents play a huge role, particularly the mom. Ethan Hawke plays the dad in it. I was just showing him the first three-and-a-half full episodes, and we were talking about this coming-up episode. And we were just kind of like, “Wow, that’s just fascinating. Kids grow a lot in a year.”

So it will be done in what, six years’ time?

I think technically eight years. Seven or eight years. Which is no time once you’re old.

You’ll be in the record books for the longest film in production probably.

Or worse, pre-production. For every two days of filming, you have to pre-produce for like a week. It’s way out of whack there. It’s an interesting side project to be doing. I have no idea where it’s going to end up. I kind of have an idea. I’m working on it.

How would you define the director’s job?

For me it’s different on different movies. I mean, it’s your taste, the vibe you lay down the visual and the working rules, that you lay down for everyone that you’re working with. So I think you set a tone for everything. Even if I’ve written it, once I’m directing it, my job is to make the film work, and I don’t care who wrote it, whether it was me or someone else. I’m more collaborating with the actor than the writer at that point. I’m trying to make it come to life in some way. You’re trying to bring something to life along the way and tell the story you’ve set out to tell, so whatever it takes. And a lot of it’s who you’re collaborating with, what department heads, what creative people you’re working with. I love it, because it hits on everything. As a younger person, I think I wanted to be a writer. That seemed to me my only area I could express myself in. I didn’t know other mediums were even open to me. But once I realized I was a filmmaker and had films in my head, I realized that was so my calling because it answered the need in me to work with others, to collaborate. When I was young, I was kind of left on my own, and just reading. I’m pretty solitary. Film got me actively engaged with others in a collaborative, creative way. That’s what I find probably the most rewarding, the collaboration aspect. It’s perhaps one-sided, because I kind of have veto power and ultimate say, so there’s a certain amount of dictatorial power in the structure, but I think within that structure you can make it work in a lot of different ways.

The impulse to build a community around yourself was evident even before you made films—you and a few others created the Austin Film Society out of nothing.

It was that alternate life where you can kind of remake your adult life different from your childhood life; you can remake it in an artistic way with likeminded people who share the same passions. In this case, it was cinema life. What joined us was the love of film, rather than blood relatives. Your friends are the family you pick. It was always at the behest of something greater, which was film. If I hadn’t been a director, I think I’d have a theater or I’d be doing something film-related for sure. I could gather the troops and use whatever leadership skills I could muster and get over whatever shyness I had for that cause. I couldn’t do it for something that dealt with just me.

A Scanner Darkly

When you were a teenager, it was sports, right? You were part of a team.

Yeah, I was always the team-sport kind of guy—baseball, football, basketball. I think because of the team efforts I had been involved in, I realized that I like being a part of a team.

What aspect of your directing process do you wish you could develop more? Is there one thing that you wish you could work on more, that you want to be stronger at?

Gosh, no, I don’t really think of it that way. It’s almost like your personality. Is there an aspect of your own personality you want to work on? Well, we all would say yeah, but the fact is you’re not. That’s how you fell off the truck. A lot of it is who we are inherently once you grow to accept that. You can consciously shift yourself in a new direction. You can become interested in other things. I mean, you do it very subtly. Everything you do, you learn a lot. A different film takes you in a different direction. You’re gaining all that knowledge, whether it’s technical—you’ve shot something, you’ve learned something technically. But I don’t think I would ever be able to remake myself or even change that much. I no longer feel restricted that way. I felt restricted early on. I was sort of like, “Ah, shit.” I had all these great films in my mind before I ever touched a camera. And the world got a little narrower when I realized, okay, here’s what I can do and here’s what I can’t. Looking back, especially my first eight or 10 years of doing this, I was very conscious. I got in acting classes, not because I wanted to be an actor, but because I wanted to be a director who could work with actors. I bought all this film equipment and taught myself. I would do entire films, not based on content, but just lighting, or editing, or camera movement. It was very, very, very systematic. I gave myself a lot of leeway to fail.

At the time of Waking Life you talked about your practice of lucid dreaming. Do you still do that and how much does that, and the unconscious in general, feed into your work?

To me, it’s not directly related to film or anything. It was just kind of a natural, weird offshoot that I had a propensity for. Just getting in touch with that was kind of interesting. I don’t lucid dream that much anymore—I mean, I do, but I don’t actively do it. To do a film about it really, really took me in that area. I wanted to find out everything I could about it. It was fascinating to live and work in that kind of headspace. I’ve always had a practical, conscious side to everything I do, but to me, that’s totally at the behest of a side that’s not rational, that just follows this kind of floating, muse/desire realm. And it’s pretty unconscious. It is pretty dreamlike. You just sort of float and daydream and technically dream. What I think about when I go to bed and when I wake up is always really important to me. If I go to bed with a question or something I’m thinking about, how I feel when I wake up tells me a lot, even in just a general vibe sense. That’s always led my decision-making. But I don’t sit down and think about it that much. A lot of being a director is just trusting your instincts. And the only way you can ever trust your instincts is to actually have honed your instincts where they deserve your trust.

That’s ironic given the recurring self-analytical characters in your movies.

[Laughter] I make swift decisions and stick with them. I’m not torn up about little things.

What’s next?

I don’t know what is next. But I have a Chet Baker film with Ethan Hawke. We’ve been developing it for a couple years with Stephen Belber, who wrote Tape. And I’m kind of writing a college movie in my own developmental world. It would be about a freshman year of college. It’s centered around a baseball team. Kind of a baseball movie, kind of a college movie, loosely autobiographical.