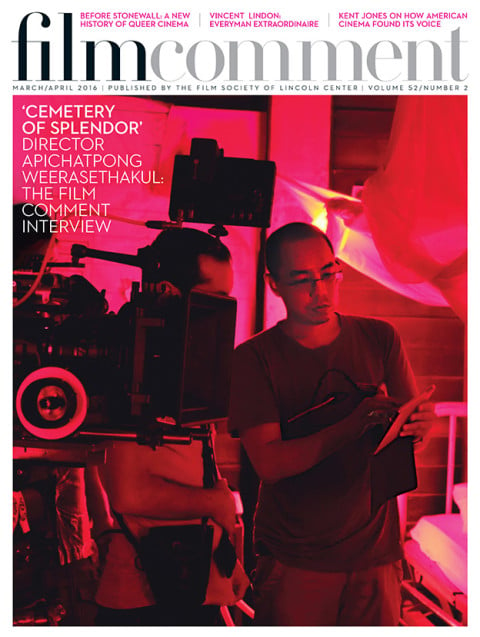

By Eric Hynes in the March-April 2016 Issue

Make It Real: The Dancer and the Dance

Two kinetic films at Sundance flipped the script in different directions

Exterior. Daytime. A street in Warsaw, jammed with unmoving traffic. Some people have stepped out of their cars, standing behind opened doors to look further up the road at some unseen activity or phenomenon, and a few are taking pictures with their smartphones. Hardly anything is moving except for the tall young man who’s dancing against the tide of cars and drivers, swinging his arms overhead, spinning and undulating—and except for the camera that’s following and gliding closely behind. Is music playing? And is it live or in his head? No one seems to take much notice of the man, save for the camera, and save for us. Yet we don’t just take notice of him: we’re with him—in step, in motion, centered on him in the frame, going forward.

From the March-April 2016 Issue

Also in this issue

By the time this sequence unfolds toward the end of All These Sleepless Nights—which premiered in January at the Sundance Film Festival but had no distributor at press time—our questions over what’s observed, staged, or spontaneous in Michal Marczak’s audacious cinematic happening are overwhelmed by the fact and meaning of all that movement. Nothing is fixed here, especially not the nature of the film and how you might make sense of it. The two boho Polish twentysomethings that Marczak trails throughout the film are in a state of active transition, and so is the film about them as it plays with the form of nonfiction. Everything’s just hurtling forward, indefinitely and beautifully.

If ever there was a ripe moment for a film this thoroughly unmoored (from genre, from expectation, from tripods, scripts, and storyboards), it’s now. At Sundance, not traditionally a hotbed of nonfiction experimentation, All These Sleepless Nights was joined by form-busters such as Robert Greene’s ethical and stylistic dirty bomb Kate Plays Christine, Penny Lane’s shell-gaming Nuts!, Kirsten Johnson’s memoir-essay Cameraperson, and Pieter-Jan De Pue’s bracing allegory The Land of the Enlightened. Yet what distinguished All These Sleepless Nights from even this group was how untroubled it seemed by its own unconventional choices. Appropriate to its milieu of Millennial searchers drinking, drugging, dancing, and loving night after night, it’s a film that doesn’t ponder over or flaunt its freedoms—it just expects us to accommodate them.

All These Sleepless Nights

Sundance presented the film in its World Cinema Documentary competition, where Marczak took home the directing prize—a coup considering how little the film tries to convince the viewer of its factuality. The camera moves with an expressiveness, as well as an invasiveness, that evokes Emmanuel Lubezki’s work with Terrence Malick—poetry not prose, gestures and glimpses of truth rather than the starkly raw or recognizably real. Even as it accumulates moments of beauty and happenstance—here a fortuitous coupling of rising smile and swooping camera, there an unfortunate clash between face and lamp post—the film reaches past the tangible to the intangible, beyond what’s seen and toward what’s felt. There’s little plot to speak of, though that doesn’t mean what transpires is inconsequential. After a rough breakup with his college sweetheart, Krzysztof Baginski—the lithe dancer described earlier—moves into an apartment with his hunky friend Michal Huszcza, embarking on a hedonistic tour of house parties and group raves, flings and romances, foolishness and philosophical musings. One night bleeds into another, scenes alternate with snapshots, but it all makes an impression.

You may get snagged on the line between fact and fiction, or whether these subjects might be more like actors, or whether all those sleepless nights are lived or devised. Meanwhile, Marczak has moved beyond such questions before you even showed up to the party. What he’s after isn’t necessarily what’s happening in the moment, but expressing what it feels like to be in the moment. The actual isn’t the endgame—it’s so much material for an ecstatic cinema.

It’s this ambition that informs Marczak’s most remarkable gambit: relying on ADR to supply the majority of the film’s sound. This runs counter to nearly 60 years of documentary practice, disorienting the viewer profoundly. Thoroughly trained by the Direct Cinema–era miracle of synch sound, we’re unaccustomed to such bifurcation, to approaching sound as something other—or more creative—than an authentication of the moment. While distancing at first, and quite possibly throughout, the ploy at least attempts to honor both the live and cinematic experiences by foregrounding the importance of music to these captured moments. Marczak doesn’t attempt to control for sound on scene, letting his protagonists move freely from one speaker-popping rave to the next, and instead controls for it in post. Thus what we see is, theoretically at least, a true response to sound… that’s been fictionally approximated for us. Whether or not you think this is successful, it’s certainly the move of a director working outside of the usual documentary constraints (unless you consider an embrace of 1940s-era sound practice more of the usual). Marczak is chasing not proof but a kind of full-bodied frisson.

All These Sleepless Nights

The partnering of subjects Krzysztof and Michal with Marczak’s custom-rigged camera is an entrancing if imperfect one, giving everyone’s movements an air of attempt, of ardent approximation. It’s a dance film even when Baginski isn’t swirling through traffic, as the camera hustles to remain in step, racking and panning to realize the rhythm. It summons Minnelli chasing Kelly, Berkeley chasing Rogers, Vertov chasing both man and machine. It also harmonizes, in a fashion, with Anna Rose Holmer chasing Royalty Hightower in another Sundance title, The Fits. As in All These Sleepless Nights, the language of Holmer’s film is constant, emotionally and psychologically complex movement. Ostensibly fiction where the other is ostensibly nonfiction, The Fits is no less a documentary of bodies in motion.

Hightower plays Toni, an 11-year-old who trains with her older brother Jermaine as a boxer in a community center in Cincinnati. Yet the center also hosts team dance classes, and Toni is equally interested in the choreography and camaraderie offered therein. Before long she’s moving freely between both, serving two aesthetics and two different gender impulses. Meanwhile Holmer moves freely between realism and heightened reality, scripted narrative and found location and cast (the film was shot in an actual Cincinnati community center, starring girls and boys who frequent it). Her camera doesn’t chase or emulate its subjects in the way Marczak’s does, at least not at first. Instead she chooses a fixed spot and lets movement play out in full for the camera. To train, Hightower runs up and down the stairs of a pedestrian overpass, she does a full set of sit-ups, she smacks her trainer’s gloves with a sequence of jabs and punches. Then to dance, she practices and practices, in groups and alone, memorizing and refining and coming into her own. She’s a young girl playing a character, but she’s also always and evidently a person in a room, breathing, sweating, tiring.

So much so that when Holmer edges the narrative into science fiction via a virus of convulsive fits among the young performers, we’re able to discern between natural and supernatural body movements, between the choreography of athleticism and that of affect. One kind of behavior seems real, the other a likely fiction. But much as Marczak chases, and tries to honestly articulate, the unbounded moments of young adults in the city, Holmer here reaches into the universally fraught territory of puberty, settling on a cinematic vocabulary that doesn’t imply a hackneyed loss of innocence so much as a raw embodiment of a complex self. There’s a continuum between a physically exerted and ecstatic body, among athletic, dramatic, and emotional performance. Her sense of dance evokes the fluidity of Keaton and Chaplin, gliding between physicality and elegance, comedy and pathos.

The Fits

Neither film cares much for larger context. We never learn about the jobs or families of Krzysztof and Michal, and we never meet the parents or visit the home of Toni and Jermaine. The latter are largely confined to the community center, but the former’s approach to Warsaw—as a morphing venue for partying—is no less confining. Documentary or fiction, it’s a trimming of the canvas, an irising in on what matters. Yet what matters isn’t easily seen. Still you have to keep chasing it, gesturing toward it, risk missing it altogether. A young Polish man pirouettes down a city street. A pre-teen African-American girl floats a foot off the ground. Believe it or not, there’s truth in the movement.

IN FOCUS: The Fits screens as part of New Directors/New Films on March 19 & 20.

Eric Hynes is a freelance journalist and critic, and associate film curator at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York.