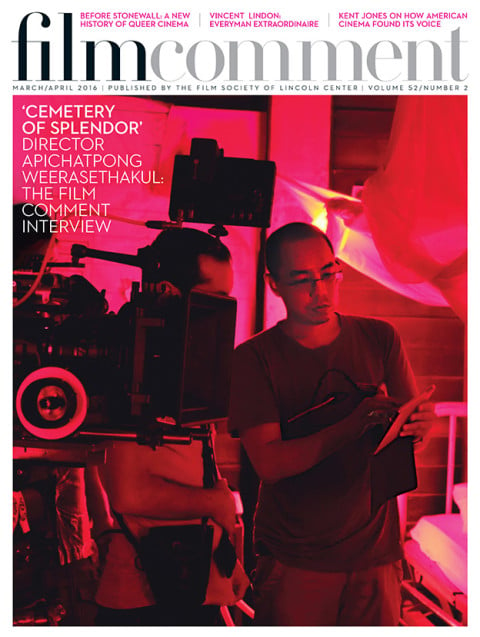

By Violet Lucca in the March-April 2016 Issue

Dream State

In Cemetery of Splendor, Apichatpong Weerasethakul employs his entrancing language of metaphor to diagnose an ailing Thailand

Dispensing with the homages to low-budget Thai film and television that gave a distinctive flavor to the magical realist goings-on of Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (10) and Tropical Malady (04), Cemetery of Splendor is Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s most openly political film. Of course, openness is relative—there’s still plenty of myth and symbolism to sift through—but the occultation is in direct dialogue with the regime set in place by Thailand’s military dictatorship. Cemetery of Splendor is also the director’s most profoundly sorrowful work, one that speaks in dream-logic fits and starts to the country’s troubled past and tenebrous future.

From the March-April 2016 Issue

Also in this issue

Set in the filmmaker’s hometown of Khon Kaen, the story primarily follows an aging Thai woman, Jen (Apichatpong regular Jenjira Pongpas Widner), who volunteers at a clinic to tend to comatose soldiers. There’s no clue to the medical cause of their mysterious deep sleep, and the men have been quartered in an old elementary school rather than a hospital, their only “treatment” in the form of light machines, formerly used on U.S. soldiers in Afghanistan as a way to encourage good dreams. The six-foot-tall, cane-like tubes slowly cycle through patterns of blue, green, cherry-ChapStick pink, and blood red, and serve as the film’s alternately dazzling and menacing visual refrain, looming over the soldiers’ inert bodies like something out of science fiction or a gallery installation. (The concept for the devices came from an MIT neurological study that successfully created artificial memories in mice by exposing their neurons to flashes of light.) Meanwhile, the hospital attendants close the windows, blocking out the outside world and enshrouding the soldiers in darkness, an inversion of the parable of Plato’s Cave.

Periodically, the soldiers wake up. The young man under Jen’s care, Itt (Banlop Lomnoi, who played Keng, the soldier in Tropical Malady), first regains consciousness while she’s massaging cream onto his chest—but often ends up passing out mid-sentence. As Jen discovers—thanks to two princesses at a shrine—the school lies on the site of an ancient kingdom’s graveyard, and the soldiers have been enlisted in a battle for the sovereigns while they slumber. This revelation takes on new meaning in light of Thailand’s wide-sweeping lèse majesté law, which has been used to imprison citizens for years at a time over minor (or completely oblique) critiques of the monarchy. Just as everyone in the country is deprived of the right to speak against the government, so must these soldiers serve unwillingly and unconsciously; conversely, their dormancy can also be understood as suggesting a public that passively refuses to revolt against the dictatorship.

Cemetery of Splendor

As in Apichatpong’s other films, we’re offered many cheery slices of daily life that express what it’s like to be in Thailand: guided aerobics classes in a park, a chicken wandering through an open doorway, food stalls in an open-air night market. But the specter of uneasy sleep hangs over it all. In one of the film’s more pointed sequences, Itt and Jen go to a multiplex and sit through a trailer for a salacious supernatural horror film. The audience rises (as is mandated by law) for the Thai national anthem before the main show, but instead of music, there’s only silence. There follows a montage of tableaux that undercut any propagandistic picture of progress: a group of homeless people sleeping under a street lamp next to a mural of Sarit Thanarat (a soldier who staged a coup in 1957 and remained Prime Minister until his death), a man gathering trash near a reservoir, and a man sleeping in a bus shelter with an ad for the “EU wedding studio.” When we return to the neon mall, an unconscious Itt is being carried out of the theater, down a maze of escalators; this is slowly cross-faded with the rest of the soldiers lying asleep in the classroom, bathed in the sinister glow of their dream machines. It’s as if Itt has been pulled down into Hell.

The idea of poking holes in the Thai regime’s false sense of faultlessness finds another kind of expression in the skin creams that are discussed during the film: at best they treat the surface, but usually have no effect at all. However, Apichatpong’s far more haunting images are those linked with the wars and genocide around the spread of communism in the region. Itt leads Jen on a “tour” of a palace that only he can see; the jungle we see is littered with cement sculptures from the Sala Keoku Temple, a park created by controversial mystic/artist Bunleua Sulilat that fuses Buddhist, Hindu, animist, and secular art styles. (Sulilat had created a similar religious park in his native Laos, just across the Mekong River, before being driven out by the 1975 Communist revolution; ironically, Sala Keoku was partially destroyed by the Thai army for being a suspected Communist stronghold.) The pair pass two of Sulilat’s sculptures, which also appear in Apichatpong’s installation Fireworks (Archives): two lovers embracing on a bench, and five feet away, the same couple posed as grinning skeletons.

Though ominous-looking, these sculptures fit at least into a religious belief in reincarnation. Yet the repeated image (or sound) of a crane digging holes outside the clinic offers no such comfort of context: the grave-like image eerily replicates what Cambodia’s killing fields look like today—a brutal invocation of death and suffering at the hands of government. At the end, Jen stares intently at these craters as kids play soccer on them, in what’s partly a reference to symbolism for awareness among critics of the regime. Whether the crane is excavating the past or creating graves for the future remains uncertain; however, it might be too late for Jen, grimly forcing her eyes open as widely as possible, to wake up from this particular nightmare.

Cemetery of Splendor

A few days before our interview, you screened Pablo Larraín’s No in Bangkok at Cinema Diverse. Why that film?

It’s super like a mirror to Thailand. It’s almost like a fantasy because we never had the chance to vote in the past year. I went to vote, but then the army overthrew the country, so my vote was canceled. No is such a clever movie to be able to share the hope: “Oh, maybe one day we can have an event like in Chile.” In Chile with Pinochet, it was 16 years until people came out to vote, and 16 years can make a lot of people forget. For Thailand, it’s been two years. So we have a long way to go considering this pattern of human abuse. It might be 10 or 15 years before we have a real democracy. By that time I might not be able to make movies, but for the audience there, I showed them: “Don’t forget. In the future we can make this kind of film.”

Has Cemetery of Splendor been shown in Thailand yet?

Not yet. I want to, but I’m not sure if it’s the right time with a lot of censorship going on. Personal safety is also a concern.

This is your most overtly political film. How is it related to your feelings about religion and meditation?

It’s a mixture of things. There’s some political influence, but I still feel that it’s not a political film. Many people can access this from many angles. For me, meditation is part of my interest, and at the same time there is a little conflict about meditation and ignorance, and the rule of karma in Buddhism. We are a Buddhist country, but there is so much violence going on. So the film is partly this push-and-pull between this serenity and sometimes these doubts.

In the film, the Buddhist goddesses that appear to Jen are from Laos. Could you talk about this relationship between Thailand and Laos?

The legends say that they are princesses from Laos, and in that period Thailand in the northeast and Laos were the same kingdom. I don’t have a very comfortable relationship with Bangkok, because I grew up in the northeast part of Isan. The more I study the history, the more it seems very sad that, because of the unification of the country, cultures disappeared and were not encouraged. So my recent works are investigations into the area—almost a yearning to reach out and bring back the past. And for Jenjira herself, her real father is from Laos, so when the country was separated, she was separated from her dad back there.

Cemetery of Splendor

There’s also the area’s history with communism, which is complicated by American involvement with Thailand.

There was a really big involvement by the U.S. with the Thai government to oppose the communism that spread from Vietnam through Laos to Thailand. People were fascinated by communism because it promised a better future. So with the U.S., you got rid of communism but at the same time the U.S. created many monsters—namely the generals in Thailand. [Laughter] And [in the film] that guy with the mural on the wall is one of the monsters.

Artwork is key in the film. What’s the significance of the use of religious sculpture?

The whole temple, with the sculptures and the signs, was always preaching Buddhism and the karma and reincarnation. And this sculpture is part of this cycle of suffering, and I think of certain periods when I feel that living here seems very depressing—being governed by this law that constantly teaches you, as if you are a student all the time living in Thailand. And also in school, we always have this propaganda, texts and poems. That’s how we grew up: the kids are taught [to be] very, very religious.

How did you choose shooting locations?

It was in my hometown. So I know all the places, and mostly I based it off of my memory growing up with this hospital, and the cinemas, and this school. I tried to combine the three elements in the film. And during preproduction, all the lake script-writing I shifted to my hometown because I felt that the story was getting more and more personal.

There is a mural of one of our prime ministers of the most brutal regime, yet people still worship him because of all this propaganda. Khon Kaen, our place, my hometown, is the home of his statue because he is considered the one who brought development to the region. But for me it’s quite shocking to see his statue and all the murals of him.

What’s the meaning of the scene when people are walking around by the water?

I found that sometimes the extras were not really good at acting, but I found that really beautiful, because it’s a filmmaking process and everything is about controlling, about being puppets. So at the lake I liked to stress this idea about puppetry and filmmaking and also the kind of feelings I have living in Thailand.

Cemetery of Splendor

Could you talk about working with Jenjira and drawing on her life?

I’ve worked with her a lot for the past 10 years, not only on features but shorts and installations. Many aspects of her life had already been translated into these works. For this film I just wanted to shoot the essence of her new life and her memories, that she’s moving on with the new husband, and hesitating about this new life and reflecting on that with the young woman.

Last fall you premiered a theater project in Korea, Fever Room, which sounded like an extension of Cemetery of Splendor.

They are in the same world, in the same fever dream that is quite a nightmare actually. The two works share the two characters Jen and Itt dreaming, sharing dreams, and sharing images in the fever room of memory. But Fever Room is more abstract, it goes beyond the narrative. They are like twins in different expressions.

It’s my first time [with theater] and when I walked on the stage I felt like, “This is the cinema.” Up there is where the film happens. And to have the audience there is the closest thing to be inside the cinema, inside maybe the womb. So I thought, “Maybe the audience will be part of this, almost a character and viewer at the same time. And with the lights shining at them.” So there’s this reflecting back and forth about watching and being watched. It’s fitting, the idea of Cemetery of Splendor and also this idea of dreaming and sleeping, because sometimes you’re just in and out of the experience—it’s a shifting perspective.