By Robert Steele in the Fall-Winter 1967 Issue

Japanese Underground Film

Filmmaker Takahiko Iimura shares his collection of avant-garde films from Japan

Takahiko Iimura came from Japan to participate in the International Seminar at Harvard University in the summer of 1966, and the consequence of his coming to the United States is unexpected. All of the other participants have now returned to their countries, and one hopes they are working furiously to better international relations. Mr. Iimura is traveling around the United States, has been joined by his wife, and plans to remain for two or three years. The reason for his becoming a traveling resident is his showing of a collection of Japanese underground films.

From the Fall-Winter 1967 Issue

Also in this issue

There have been screenings of his film collection at The Movie, a theatre operated by Mr. and Mrs. Raney in San Francisco, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Harvard, Yale, the Cinematheque in New York, Sarah Lawrence College and many other colleges, universities, adult-education centers, and film societies.

The showings at Yale have brought Iimura abundant free publicity that would have cost him thousands of dollars had he purchased it via the advertising firms of Madison Avenue. “Mob of 1,000 Seeking ‘Skin Flicks’ Disrupts Showing of Japanese Films” and “1,000 Yale Students Disrupt Art Film” declared The New York Times 10-22-66. The Times reported: “A chanting, catcalling crowd of 1,000 Yale students tried to attend an experimental film that featured ‘eighteen minutes of the art of creation itself.’ The crowd, which shouted obscenities at authorities, was loudly castigated by film sponsors standing in the doorway of the University Arts Gallery Auditorium. The films are creations of Takahiko Iimura and were sponsored for public showing by the Cinema Club, an undergraduate organization. An arts-history instructor and faculty sponsor of the club accused the university’s student newspaper of fomenting the loud frenzy by printing a ‘lurid, sensationalist’ article. The university police arrived on motorcycles and on foot to keep the pushing, shoving, and loud mob from disrupting street traffic.”

The Yale Daily News 10-20-66 reported: “An excited and unruly mob, estimated by campus police at nearly 1,000, nearly prevented the showing of experimental Japanese films in the Art Gallery last night. The crowd began forming in front of the High Street entrance to the gallery an hour before the scheduled 8:30 showing. By 8 o’clock the crowd had grown boisterous and had spilled over into High Street. When a taxicab attempting to pass through the archway sounded its horn, the crowd booed and grew more excited.

“Pushing and shoving spread as persons attempted to get closer to the door to the gallery. Several groups of students began to Chant, ‘Open the doors’ and ‘Skin flick.’ Students near the entrance to the art gallery said they were nearly crushed. Shortly after 8, Standish Lawder, faculty sponsor of the Cinema Club, appeared at the doorway. He told the crowd, which had by then become a mob, ‘You won’t find the spectacle described in the lurid, sensationalist Yale Daily News article. The films will be cancelled unless you stop this irresponsible mob behavior.’

“The crowd continued to chant and yell obscenities, threatening to storm the barred entrance to the art gallery. At 8:45 five campus policemen stationed themselves at the door and prevented anyone else from entering the building. High Street was left in shambles. Papers, bottles, and . beer cans littered the area.

“Mr. Lawden later told the News he thought its article about the movies was a distortion of ‘what this kind of film is all about. There is more flesh right now in local theaters,’ he said.”

The hullabaloo was caused among the students by a statement in Reed Hundt’s article in the university newspaper—”LOVE, the most notorious of all Iimura’s films, eighteen minutes of the act of creation itself, all done with lenses of extremely short focal length, and with magnifying lenses so that pubic hair and the genitalia themselves take on new and often unrecognizable aspects the cast is anonymous.”

After the incident the editor of the News published the following statement: “The News regrets students chose to react the way they did to yesterday’s article. However, descriptions of the films which appeared in print were quotations from the movies’ promotional brochure—Ed.”

I have a copy of Iimura’s promotional brochure on his films, and the editor of the News is correct. The story in the News is lifted word for word from the brochure. Tako’s films—that’s the name his wife uses for him—are conceived and intended to evoke erotic responses. Another showing of his and other Japanese underground films was held at the Gate Theatre in New York City, advertised as “Japanese Erotica.”

ONAN, in my opinion Iimura’s number two erotic film, was described by Sight & Sound as a “strange shocker.” In his brochure Iimura says of the film—”A young man lies naked in his bed and burns holes in the breasts and pubic regions of pictures of girls taken from magazines. Excited, he curls upon himself, he is delivered a strange stone Object.” (It looks like a large, plastic egg.) “Running through the streets in his underwear, he meets a girl and drops the object. Two versions of this film exist. The second is punctuated by clip holes in the middle of the images.” Films in Review described the film as a skillful, sexual fantasy. Shocking.”

There is nudity in the film but, regrettably, it is more cautiously handled than shocking. Camera angles and sheets are played around with—sufficiently to ensure the film’s being acceptable for exhibition. Despite Iimura’s statement that there are no compromises in his films and that they are not intended for audiences, a most quizzical statement, the handling of nudity suggests foresight to skirt censorship.

ONAN was shown at the Third International Experimental Film Festival in Brussels, 1963, and he received a special prize.

I met Iimura soon after he arrived at Harvard. The reputation of his films had preceded him, so I was disappointed not to find him looking like an erotic man. Since then, we have spent two long evenings together, and I have been with him during five screenings of his films. No one would guess from knowing him that his films were the occasion for a near-riot at Yale. He was my guest and showed his films to full houses for a film series that I direct in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He offended no one, and he titillated no one. From looks and manners, Iimura could be a Japanese scientist or business man visiting the United States. Unlike some of the film makers of the American underground, his appearance is not at all exhibitionary or self-indulgent.

Before he was graduated from Keio University in 1960, Iimura was resolved to be a filmmaker. He will be impatient until he has made his first feature-length film. He was born in Tokyo in 1937, and until his arrival in the States his film activities had been confined to Tokyo. He had his first one-man show, called “Cinema Play,” at Sogetsu Hall in Tokyo. With the help of Donald Richie, he organized Japan Film Independents. This is an organization of somewhat like-minded filmmakers who help each other with financing and exhibition. They have in common a devotion to film, little or no formal training, and no expectation of competing with commercial cinema. They use film to express themselves personally and privately—and occasionally artistically.

Iimura, who is 29, made seventeen films in Japan (he knocked off his eighteenth the summer of 1966 with the Harvard Yard as his location). He had his second one-man show in Tokyo in 1964. His IRO is the result of his shooting colored inks mixing with melted waxes moving into water. DE SADE is made from eighteenth-century engravings and is handled to suggest LES 120 JOURNES DE SODOME. DADA 62 is a dadaist film technique used to show Japanese neo-dada painting and sculpture. THE MASSEURS has a theme, according to Iimura, taken from Jean Genet. It is a dance recital by Tatsumi Hijikata and Keijin Ono and their troupe that looks like a cross between a karate workout and a pantomimed drama. UKIYO UKARE present details from the shunga, pornographic wood-block prints of Harunobu, Utamaro, and others. THE MEMORY OF ANGHOR-WAT is made up of stills of temple compounds of Anghor. Most of the stills were made by Kenji Kanesaka, who has been a student at the University of Chicago and has attracted my attention with a movie of his impressions of Chicago, called SUPER-UP.

Iimura’s INSIDE AND OUTSIDE reminds the viewer of Stan Vanderbeek, because the latter has become synonymous with a collage technique using cut-up photographs of fashion models. Iimura also animates similar photographs, examines skin, flesh, and muscles with a microscopic lens, and finally gives us white leader for as long as we can stand it. JUNK sorts out and peers at flotsam on a beach. WHY DON’T YOU SNEEZE? is blatantly inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s ANEMIC CINEMA. ROSE COLORED DANCE is a photographic recreation of Tatsumi Hijikata and his Black Dance Troupe expressing the birth of a virgin from the womb of a transvestite. I SAW A SHADOW is made only from shadows—the shadows of a camera and a girl that have a dreamy relationship.

Although Iimura feels his A DANCE PARTY IN THE KINGDOM OF LILLIPUT may be his most surrealistic film, it seems cubistic to me. Also he describes it as a comedy, but after seeing it with three American audiences, I have yet to hear much laughter. It is divided into short scenes announced by titles like chapters of a book. We see the lame protagonist in a crowd and then running upstairs. The first shots show the hero naked, and in Iimura’s films, naked is naked. The opening shot has the full figure of a man, back to the camera and centered in the frame. In the second shot the man again is in long shot, but he is standing in profile facing right. The third shot duplicates the second except that the man is facing left and his genitals peep out behind his hand. Were we accustomed to Japanese radio, and if we felt superior to morning-exercise pro grams directed by radio, the regimented counting for push-ups might amuse us. The first “chapter” concludes with the man in a waist-to-feet medium shot, urinating with his back to the camera. Audiences titter at this from surprise or embarrassment rather than amusement.

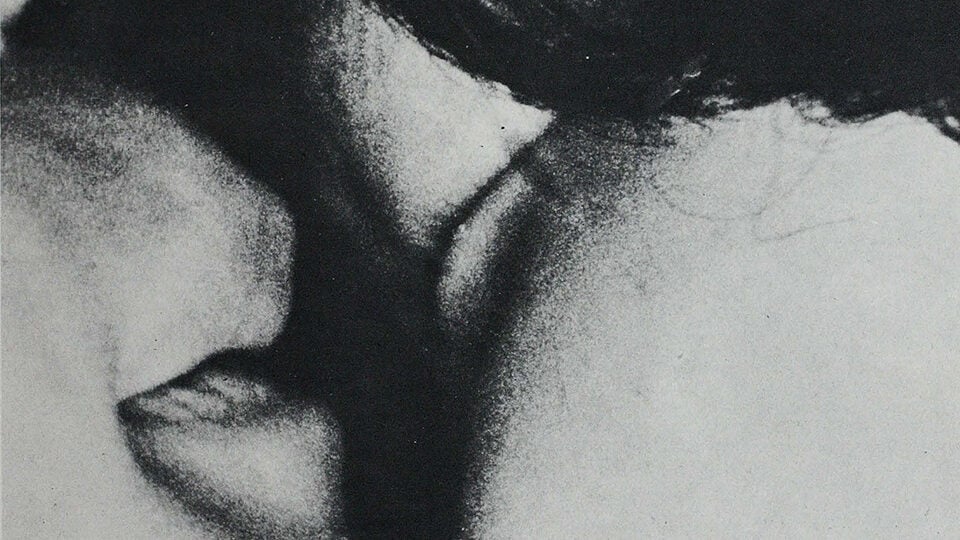

Ai (Love) (Takahiko Iimura, 1962)

“

LOVE, an Iimura film, 8mm and 16mm B/W 18 minutes, using lenses of extremely short focal length and magnifying lenses go that pubic hair and genitalia take on new and often unrecognizable aspects. Music is by Yoko Ono. Cast is anonymous. I have seen a number of Japanese avant-garde films at the, Brussels International Experimental Film Festival, at Cannes, and at other places. Of all those films, Iimura’s LOVE stands out in its beauty and originality, a film poem, with no usual pseudo-surrealist imagery. Closest comparison would be Brakhage's LOVING or Jack Smith's FLAMING CREATURES. LOVE is a poetic and sensuous exploration of the body . . . fluid , direct, beautiful.” –Jonas Mekas.

The cleverest idea in the film is seeing a man run up the outside stairs of a five-story building. Between each ascent the camera tilts down to the front of the building, and viewers wait for him to come down, burst out a door, and then repeat his run up the outside stairs. Iimura’s touring collection contains other Japanese underground works. Katsuhiro Tomita’s THE MARTYR is myth and paradox. It intermingles obsessions, violence, neurosis, and Eastern and Western music. The film opens with panning shots over monuments in a cemetery. The camera stops as a young man rapes a middle-aged woman. Then he kills her. From Iimura’s verbal introduction or from program notes, we know the woman is his mother. A gang of young men attack the rapist. They put him in a casket and nail down the lid. At night, to the accompaniment of marching and Nazi chanting, the young man in the box is carried into a city and deposited in the middle of a street. Somehow, he has escaped and he walks down a street and through a park, where he sees lesbians making love on a bench. Then he is in the house of the lesbians. One has made a plate of fudge. A ritual with candelabra takes place over the fudge. Then it is eaten by all. The boy is followed by a girl into the same cemetery where he killed his mother. He rapes and chokes her at the feet of a huge Buddha. Because oil is burning and smoking in front of the god, we know the Buddha is not a monument but a shrine. Then we see the young man’s phantasies of shooting a girl. She dies horribly. A mannequin is put on a cross, clearly symbolizing the crucifixion. Instead of the mannequin’s being shot, as seems to be attempted, as well as crucified, a Greek bust that dominated the lesbians’ room is shattered by a shot. The young man is attacked by a gang. He fights them and after killing all of them he dies. The film concludes with a mannequin’s burning. This image without question must have been suggested by Salvador Dali’s “Self-construction and Boiled Beans” (“Premonition of Civil War”).

Although director Tomita was born only in 1938, he is said to have made many films. All are said to be distinguished by his delineation of compulsions recognizable in the West as well as the East.

COMPLEXE is described by director Nobuhiko Obayashi as a film about man’s place in the world—or lack of it. This is Obayashi’s finest film. He was born in 1938. The film was an invited entry at the 1965 Tours Short Film Festival. The film is funny because the lead is a deft comedian. He is funnier than the stop-motion photography that enables him to skate through the streets. No longer are we sent into gails of laughter by excessively slow or fast-motion photography, but the single-frame exposure technique in this film comes off with much finesse and imagination. Despite his skating speed, our man is caught by a gang of boys and disrobed except for his shorts. We think he is going to be beaten, but he is tickled and all have a jolly time. Supposedly, COMPLEXE is a parody on Western cinema and kids WEST SIDE STORY and THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME. The throwing of a banana peel at the camera, upon which the cameraman slips, concludes the

Masao Adachi, born in 1940, studied at Nippon University’s Film School. He was graduated a year after his second film, RICE BOWL, was made. It is an allegory about shame, sin, death, and futility. Adachi became known for his first film, THE HOLELESS VAGINA, because until recently Japanese authorities blocked its being shown. RICE BOWL reminds a viewer of Druid human-sacrifice rituals. Spewing blood and death abound; they are means of a sacrifice led by a woman wearing a white robe. The men she has in her power are dressed like monks. They dote on her wishes and respond without question to her commands. At moments the film reminds one of medieval escapades Bergman has created close-ups of lips kissing trees are intercut with paintings of a girl in Yoichi Takabayashi’s MUSASHINO. Shooting through holes, giving an iris-in effect, suggests that the viewer is seeing the film as a voyeur. Completed in 1965, the film is Takabayashi’s most recent work. He is said to be the most productive experimental film maker in Japan. Baldly the film maker has told audiences what he is trying to do—”to make a real erotic film.” He uses plenty of nudes against the scenery of the Musashino Plain. The film did not move me erotically. It is repetitious and far-fetched. The music is as weird as can be and pleasantly consumes one while waiting and hoping the mist or dry ice will vanish so that one can experience what the film maker seemed to intend.

Promoting the Japanese Film Independents is Iimura’s mission in the United States. The best by far of the films that he has made available for us is AN EATER. The film was made in 1963 by Kazutoma Fujino. It makes one feel that Fujino, born in 1928, is ready to take on a feature. It is flawed and prolix in spots, but it is original and hypnotic. Donald Richie, author of The Films of Akira Kurosawa, and co-author with Joseph Anderson of The Japanese Film, says that Fujino is a respected and successful surrealist painter.

In AN EATER, two waitresses serve elaborate dinners to Western-dressed Japanese men and women in a Western-looking restaurant. One waitress has a sensitive and frail beauty. She does her work with dispatch until the increasing grimaces of persons chewing and the noises they make go to her head. She faints. We see her stretched on a table as if to undergo surgery. The chef is her surgeon. After he makes a foot-long abdominal incision, he removes food like that we have seen served in the restaurant. He pulls a whole cabbage, many eggs, and finally a man’s face out of her. The waitress comes out of her faint and resumes serving, then faints again. This time there is nothing left for a surgeon to do to her. She vomits. For what may be five minutes or even fifteen, she vomits—all over the floor, over the customers, over the whole restaurant until the vomit flows over the balcony onto the floor below. After acres seem to be covered with vomit, in the final shot, the waitress is still vomiting.

AN EATER, like almost every Japanese underground film I have seen, is too long because it is overdone. Its double climax weakens its impact. The photography is good enough to be unobtrusive, but the natural sound is so distorted and exaggerated that it is nightmarish as well as the picture. AN EATER is an original film and succeeds in giving a horrible experience to a viewer.

Donald Richie, the American authority on the Japanese cinema, has had an interest in all of the experimental and avant-garde work of Japan. As stated earlier, he has assisted the Japanese Film Independents. Richie is not such a “gone” scholar that he is oblivious to the delights of production himself. His contribution to the Japanese underground is a four-minute anecdote called LIFE. He wrote, directed, and photographed it in 1964. The best part is the sound track, made wholly from a voice which makes a yodeling sound that no words or letters of the English alphabet can suggest. The voice makes a nonsensical sound that varies in pitch and tempo and succeeds in carrying the movie. The action: a young man chases a girl and more often money. Perhaps it is a chase after the same thing, because money when it is found is flashed in front of the girl. The unities of Aristotle are observed in order to reveal the cyclic nature of man. Except that it begins with an adult man, loving and chasing, and ends with a two-year old boy, who walks sufficiently well to chase money, the film ends as it begins.

In the case of Richie, the Japanese underground spread to—or should we say contaminated?—an American. Also, because Kenji Kenesaka has taught at the University of Chicago, it has spread to Chicago. He made a film called SUPER-UP about the way he sees Chicago or perhaps all large American cities. Being an American-Japanese production, it is the most lavish of all of these films. It is in color and cost $2,000. Probably all of the underground films mentioned in this article could have been made for this amount. Marvin Gold of the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency in Chicago worked on the film with Kenesaka. It is expertly made and is distributed by Brandon Films of New York, Chicago, and San Francisco. The only other distributor to touch the other Japanese films mentioned here is the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, 175 Lexington Avenue, of New York. SUPER-UP had the distinction of being shown in September 1966 at the Twelfth Robert Flaherty Film Seminar. Because it is an atypical film for this Flaherty Seminar, which devotes itself to serious and conventional films, it was shown under improvised circumstances to only a minority of participants.

Although SUPER-UP was made by a Japanese undergrounder, who is now in Tokyo but hopes to return to the States, it is not foreign to those who see film with non-U.S. Information Agency eyes. The familiar film that it most apes is Ben Maddow’s THE SAVAGE EYE—a film that looks at the sordidness in American life and concentrates on the cults and perversions of Los Angeles. SUPER-UP shows truck-and train-loads of automobiles. Then acres of automobile cemeteries. The blare and tawdry neon lights of the city are intercut with the trash on the streets. The film overwhelms a viewer with a recital of urban waste and ugliness. Many billboards and signs make clear what this Japanese film maker sees as our sickness.

Kenesaka spent five days looking at Chicago to get ideas for his images. He wrote no treatment or script. Shooting was done in twelve days at night and on week-ends. Ron Kaski spent four months editing the film. SUPER-UP is harrowing and at moments terrifying.

Kenesaka and Kaski had difficulty getting Chicago laboratories to print their work. Some objected because of the nudes. One had no objection to printing nudes but said—”That’s not a problem, but Seven-Up is one of our accounts.” Except for SUPER-UP, all of the Japanese experimental films mentioned in this article need cutting. They are overlong because of their excesses, repetition, and irrelevancies. I may be missing some of their quality because I may not be able to free myself from the pace and tightness of Western dramaturgy, but all the films except Richie’s seem redundant. This is a minor negative criticism. Any film maker anywhere who is making his first films —and editing as well as conceiving, directing, and shooting them—offends in this same way. Understandably, a film maker becomes a lover of his work as he does of his own baby, and he loses his detachment. He cannot be ruthless when ruthlessness is necessary to shape and point a film.

These Japanese filmmakers feel their works have something in common with haiku. Their films are intended to be terse, inner statements with meanings that must be inferred rather than directly communicated. Their films are objects like ikebana: something to admire, something to disregard. Sometimes these objects are curiously interesting, sometimes dull, sometimes shocking. All refrain from making rational compromises, and they strive to be faithful to their makers’ visions. The films are Japanese expressions, and the imagination and originality in them evidences one’s seeing in them the primitive works of Japanese directors of the future. They are comparable to ENTRACTE of Rene Clair, made in 1924, and LA PETITE MARCHANDE D’ALLUMETTES, made in 1927 by Jean Renoir. Young film makers are experimenting in the way they want to experiment. They are not merely anti-commercial and non-conventional, but they have ideas that they wish to express by way of film. While Japanese in subject, ritual, and humor, the films are not foreign to the misery, sadism, violence, perversity, and preoccupations that other young, avant-garde film makers have in their works all over the world.

Takahiko Iimura surprises when he talks without apology or embarrassment about his films being obscene and pornographic. He uses these words as if they describe his genre of films. Also he says he is making underground films. Some so-called underground film makers of the United States cringe at that sobriquet, but not Iimura. Ever since the showing of a collection of American underground films in Japan, Japanese other than Iimura have been committed to the under ground movement. Iimura uses the term underground as if he were describing scientific, mental-health, or animation films.

Iimura sometimes speaks enigmatically but in a way that evokes confidence in him as the leader and spokesman on behalf of experimental film makers in Japan: “The age of the new cinema will come. You will find it everywhere—in every town and at your very desk. Film will make you see in the dark and blind you in the daylight. It will force your eyes open by knocking them out. What will you see in your new blindness?”

Prof. Steele teaches film at Boston University