By Phillip Lopate in the March-April 2003 Issue

The Son

The endless toil of conflicted hearts becomes the stuff of moral catharsis in the hands of Belgian master craftsmen the Dardenne Brothers

In three intensely naturalistic, psychologically powerful features, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, a Belgian brother directing duo, have developed their own signature cinematic style (characters shot close up, often from the back), carved out their regional universe (working-class Liege), captured numerous awards (including the Palme d’Or for Rosetta at Cannes), and catapulted to near the top of the international festival circuit. This does not mean the cultivated American public has the foggiest idea who they are. But before we lambaste our countrymen for their imperial incuriosity, let us frankly admit that the Dardenne Brothers’ films are not exactly date movies ripe for indie crossover success: they are rigorous, wrenching, and somewhat grim workouts, albeit exciting and fresh.

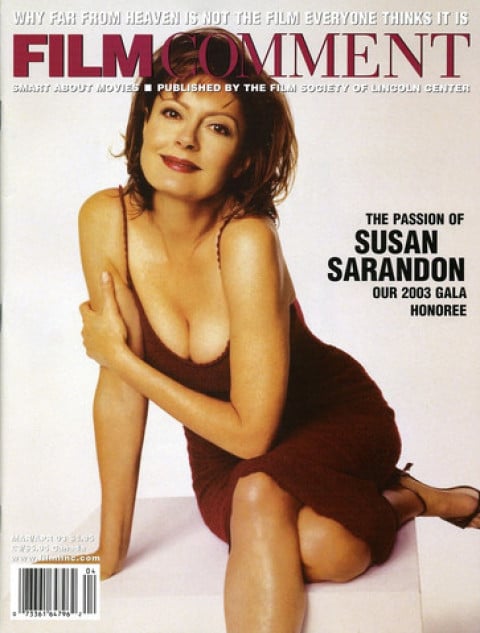

From the March-April 2003 Issue

Also in this issue

The Dardenne Brothers, now in their fifties, learned their trade as documentarians (Belgium has a strong, gritty nonfiction film tradition). Traces of industrial documentary persist in their use of direct sound (harsh, clanking noises, no music scores), a loving factualism, and a respect for real-time work processes, now joined to a brisk narrative style of jump cuts and economical storytelling. The contradiction between these two senses of duration forms a complex tension of its own.

Typically, a Dardenne film follows one anti-slacker character on his work rounds while trying to resolve a crisis of conscience. In La Promesse (96), it is 14-year-old Igor, tom between loyalty to his slimy, immigrant-exploiting father and an African woman widowed by his father’s crooked practices. My personal favorite, Rosetta (99), follows the eponymous heroine, a teenage girl who pits herself against the world in an effort to distance herself from her alcoholic, sluttish mom and become self-reliant.

The Son reverses this generational pattern, focusing not on an adolescent resisting the influence of a corrupt parent, but on a middle-aged man who must forgive a teenager’s horrific destructiveness. The Son’s Olivier is a carpenter teacher at a vocational school for troubled youth, divorced and living a spare existence, except for his work, where he feels “useful.” He seems stoic but burdened with an inconsolable sadness, which, we come to learn, stems from the death of his son, killed by an eleven-year-old thief in a botched petty robbery. (Presumably his marriage was also a casualty of that tragedy.) Now the killer, having served five years in Fraiport, a juvenile lockup, is paroled to Olivier’s center. Olivier must decide whether to take him on as an apprentice.

The instructor is played by Olivier Gourmet in an extraordinarily physical (and cerebral) performance that won him the best actor award at Cannes. Gourmet has been a consistent Dardenne Brothers’ standout, as the slimy father in La Promesse and the girl’s boss in Rosetta. Here he goes further, inhabits the role until there seems to be no boundary between character and actor (no accident that both share the same first name). The Dardenne Brothers acknowledge this ambiguity in their shooting diary notes: “The storyline is the character, opaque, enigmatic. Maybe not the character, but the actor himself: Olivier Gourmet. His body, the nape of his neck, his face, his eyes lost behind his glasses. We could not imagine the film based on another body, another actor.”

You can read the complete version of this article in the March/April 2003 print edition of Film Comment.