By Olaf Möller in the September-October 2019 Issue

Of Human Bondage

Though known for science fiction, Piotr Szulkin increasingly described the way we live now and the persistence of the powers that be

When Piotr Szulkin died last summer, he was still fondly remembered as one of Polish cinema’s most unique voices for his spirited social satires in the guises of science fiction and horror, such as The War of the Worlds: Next Century (1981) and O-Bi, O-Ba: The End of Civilization (1985). Szulkin’s reputation has persisted despite the fact that he hadn’t made a new feature in over 15 years at the time of his death. Born in the aftermath of World War II, he had thrived in the ’70s and ’80s, but times had gotten harder and harder for most of Poland’s old guard by the 2000s. While the Wajdas, Zanussis, and Machulskis knew how to navigate the political rapids of whatever form the post-Communist country was taking at the moment, oddballs like Szulkin had trouble finding financing in a new capitalist world that was as obsessed with forgetting the past as with supplying a (festival) market that prized youth and debuts.

It’s telling that Szulkin’s second-to-last fiction feature—Femina (1991), a Buñuel-esque melodrama with baffling Żuławskian undertones—was made in 1989-90, before the end of People’s Poland. The Communists had less of a problem with a pesky, politically caustic visionary than the free market apologists, even if they shelved his films from time to time. During the Cold War, a dissenting mind was always good to have around, as it showed that the state was free enough to produce such artists and their work; nowadays, film culture prefers obscurantist collaborators with “just enough” attitude. But at the same time, reading Szulkin’s often spectacular films as mere parables about the totalitarian side of People’s Poland is misguided. The apparatchiks, mad scientists, and power-hungry despots found in two of his best-known films, Golem (1980) and The War of the Worlds: Next Century, are not specific to State Socialist countries, as history has continued to make apparent.

Szulkin’s interests in systems of power, wherever and whatever they are, are present from early on, but didn’t necessarily take the shape of genre. Let’s enter the Szulkin labyrinth by way of an eerie 1978 documentary short about women’s lives in People’s Poland, Working Women, arguably his first masterpiece. The women seen here are Szulkin’s original robots, and this is no allegory—just a brutally honest depiction of what it means to be a cog in society’s machine. Constructed rigorously, Working Women consists of six tableaux vivants of identical length showing different aspects of women’s working lives. First, the workers are shown joyfully leaving the factory en masse, in the obligatory nod to the Lumière Brothers. Then, a series of isolated workers are each observed lost in the midst of some repetitive, mind-numbing, and, in some cases, potentially dangerous activity (sweeping, driving a tram, slicing up fish, operating a circular saw, etc.). By the end, a woman is shown at home taking care of a madly crying baby while porn plays on the television. The final shot depicts household work as just another job, and sex (supposedly a bonding act) as only another instance of alienation. As if all of this weren’t depressing enough, Szulkin filmed Working Women at 16fps and then doubled each frame, creating a jerky movement that makes the women look more like puppets.

O-Bi, O-Ba: The End of Civilization

From the September-October 2019 Issue

Also in this issue

Szulkin pulls no punches in portraying how desolate and desperate women’s lives are, and not as a result of their work in the public sphere, where most Communist countries were more progressive than their capitalist counterparts. Rather, a patriarchal structure persists in every woman’s domestic life, even when the men are conspicuously absent, as they are in Working Women. Years later, these themes would be echoed in Szulkin’s rarely discussed feature Femina, which he made in close collaboration with celebrated feminist writer Krystyna Kofta (with whom Szulkin would work again soon for the 1992 Teatr Telewizji production Pępowina). In Femina, a woman named Bogna is forced to return home and take care of her mother’s funeral while her husband is away furthering his career as some kind of intellectual, unable to support his wife in her hour of need. The horrors that this unexpected journey triggers for Bogna are manifold, ranging from nightmares involving a Stalin-incubus to brutal guilt trips anchored in an ultra-conservative Catholic upbringing that places lesbian desire at the core of all Evil when she meets an old friend she once had feelings for.

Szulkin posits that Communism and Catholicism might be more closely interrelated than previously acknowledged. Did State Communism function so well for so long because it took the place of power held by the Catholic establishment, or, worse, did the two reinforce each other? Femina received flak in certain quarters for its treatment of female sexuality, but perhaps what really got under people’s skin was the interchangeability of oppressive systems. For Szulkin, this kind of structural violence is the true original sin of Poland. It’s certainly not an accident that one of Szulkin’s most enigmatic shorts, Copyright Film Polski MCMLXXVI (1976), simply portrays an Edenic apple slowly being crushed in a vice (destroy the gate to wisdom, destroy the female challenge?).

Not that Szulkin had high hopes for mankind’s future. The bleak title credits of Golem, probably Szulkin’s best-known film internationally, end with a shot of squirming white laboratory mice, as if to say: this is how humans are, stumbling over one another—even though we feel unique, we are little more than indistinguishable beasts not long for this world. The film is set in a postapocalyptic totalitarian state where medical doctors engineer and control human beings through technology, and yet the Golem myth is far from central to the narrative. The reference to Gustav Meyrink’s novel The Golem, published in 1915, mostly serves to add poignancy by evoking a world at war. In fact, all of the film’s fantastique aspects look on closer inspection to be diversionary—more of a Brechtian distancing device than a real attempt at a genre film. Golem is first and foremost a slightly paranoid neighborhood comedy––albeit drained of all mirth and laughter. Pernat, the film’s protagonist, stands out among his neighbors for his looks and manners; he’s a technologically enhanced human whose memory has been erased and who’s mainly good for working very hard. If that sounds like science fiction, most of the prying and squabbling among the neighbors that make up goodly portions of the film was something ordinary Poles probably knew all too well from their daily lives in communal housing structures, where everybody lived too close to one another for comfort. O-Bi, O-Ba would expand upon that motif even further, picturing an entire underground shelter system of rooms, passages, hallways, and aisles—the apartment block for a civilization rebuilding after yet another of those nuclear Big Bangs that Szulkin, like most ’80s intellectuals, was obsessed with.

Szulkin seems to have identified strongly with Golem’s befuddled Kafkaesque antihero, a victim of the system. But he appears in the film as a shady representative of the forces of oppression: a TV director. Television as an instrument of totalitarian control or manipulation and a dangerous illusion of instantly available reality became a key element for the works to follow. In The War of the Worlds: Next Century, the main character is an agitating TV personality à la Sean Hannity, while in Ga, Ga: Glory to Heroes (1986), a man is accused of crimes so as to supply the state with a victim for a public execution, presented in a stadium like any concert or spectacle.

The War of the Worlds: Next Century

The War of the Worlds is a delightfully free interpretation of H.G. Wells’s book, and in 1981, it begged to be read as an allegory of General Wojciech Jaruzelski’s coup d’état in December of that year. But the film looks and moves more like noir than science fiction, a sense that is underlined by the casting of a slightly puffy Roman Wilhelmi, the period’s specialist for alienated characters with a certain sleazeball appeal. Wilhelmi plays Iron Idem (what a name!), the broadcaster/host whose standing with the establishment rises and falls according to the official attitude toward the Martian invasion, ending finally with his shooting on live TV. That however turns out to be a mere media stunt, as Idem in the end is allowed to walk away free, the execution having been staged for the public. The film’s atmosphere of all-pervasive corruption suggests a radical disintegration of the body politic, beyond hope of salvation. Jaruzelski is merely a symptom of that process, not the cause—and similar to Idem, he’s expendable. Like Szulkin, Jaruzelski slowly faded out of the picture post-’89: after resigning from his official posts (not always voluntarily), he stayed in the public eye, became a supporter of Aleksander Kwaśniewski (more on him soon), and was at some point threatened with a court case for various crimes connected to his rule, only to claim ill health and finally die.

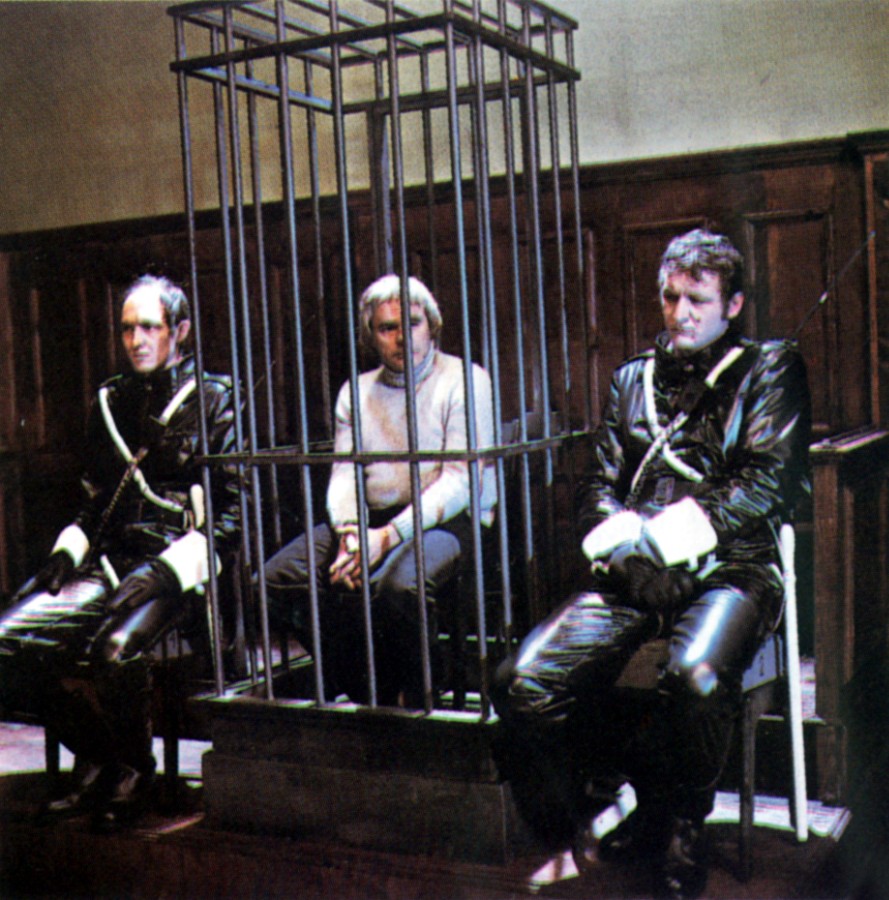

After Wilhelmi, another casting coup for Szulkin was Jerzy Stuhr in a later portrait of televisual dystopia, Ga, Ga: Glory to Heroes. The comedian and icon of the cinema of moral dissent plays Chudy, a high-ranking representative of power on the planet Australia-458. Stuhr is the foil to an explorer/conman named Scope (Polish acting axiom Daniel Olbrychski), who’s offered the opportunity to become a star by being massacred for an audience, Roman style––but first, he has to commit a serious crime so that he can properly be brought to court and sentenced, the show-trial way! Scope agrees to the deal, only to pull a fast one on the powers that be, in league with an underage prostitute bearing the chillingly ironic name Once, whom he meets and takes pity on. In a rare bit of cheeky optimism, Szulkin allows his heroes to get away victoriously.

The most abstract treatment of public broadcasting’s powers, the politics of spectacle, is to be found in O-Bi, O-Ba. In this iteration of a rubble-strewn world, humans believe in the myth of a savior space vessel called The Ark—but that belief is only kept alive by mood enhancers. Their underground society relies upon a spectacle that is constantly promised but never delivered, thereby fostering a culture that lives in a perpetual state of frustrated expectation. Sound familiar?

Post–people’s Poland, Szulkin was mostly sent packing to television, the subject of so many of his Communist-era films as well as his own training ground. His last television work was a ’97 Teatr Telewizji production of Brecht’s 1941 anti-Fascist play The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, a perfect companion piece to Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. And indeed the final entry in Szulkin’s feature filmography was King Ubu (2003), an adaptation of Jarry’s symbolist grotesque. While little-loved and shown even less, it was the only film that had anything of importance to say about post-Communist Poland during Kwaśniewski’s presidency (1995-2005). The story of a king’s venal and violent reign arrived right on time to be seen as a comment on one of the biggest corruption cases in modern Polish history, the Rywin Affair. That King Ubu looked and sounded like the ’80s—with its gorgeous costumes, outlandish acting, and orgiastic use of filters—made a point nobody wanted to hear or see: nothing had really changed. Originally started in the ’90s as a parody of President Lech Wałęsa, the film came just in time to tell it like it was with Kwaśniewski. What’s more, it looks like a documentary on at least half a dozen presidents of other NATO nations in office right now.

The most depressing thing one can say about Szulkin’s cinema is that its themes and subjects don’t seem to be growing old or stale any time soon. Yet the horrors of totalitarianism and of the masses being made into pawns for the dubious gains of the few have never been described with so much panache. What Szulkin offered was an iconoclastic spirit so fierce that his films not only provide solace but also spark the kind of anger needed to rise against tyranny with success. Maybe.

Sci-Fi Visionary: Piotr Szulkin runs from September 6-8 at Film at Lincoln Center.

Olaf Möller is a Cologne-born and -based film critic, writer, and curator.