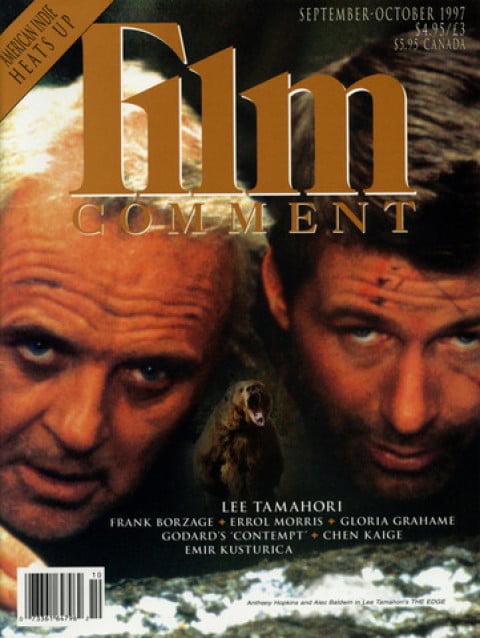

By Donald Chase in the September-October 1997 Issue

Gloria Grahame

In praise of the naughty mind

Not long before she died in 1981 at age 57, Gloria Grahame, who had acted in films signed by Frank Capra, Nicholas Ray, Josef von Sternberg, Vincente Minnelli, Elia Kazan, Fritz Lang, and Fred Zinnemann, demolished them all in one sweeping statement. “Those men never directed me,” she told an English stage director with whom she was currently working. “I’d go home and work on it with my mother, then come in and shoot it, and that would be that.” If she gave credit to anyone other than her mother, a Shakespearean actress-become-Los Angeles-drama coach, it was to Bill Watts, her dialogue director on the 1947 Crossfire. A dialogue director's job is to learn lines with actors, presumably in accordance with a director’s interpretive notions, but this one apparently did much more with Grahame. Watts, she told the Brit entertainment mag Time Out in 1978, “first made me realize how to play movies. It’s thinking... All he did was talk to me about who the character was, where she was, what she was, until I was so immersed in what it was all about. After that, maybe I just did it for myself.”

From the September-October 1997 Issue

Also in this issue

Of course, Grahame was by this time largely a figure of celluloid memory: she was the flirtatious goofus of Zinnemann’s Oklahoma!, but, more typically, she was the Ur-noir siren (of Lang’s The Big Heat, in particular) whose cracked, lispy purr issued from an odd, tortured, liberally painted mouth poised somewhere between sadism and masochism. So maybe she was trying to discourage her interlocutors’ nostalgia—for her former self, her films and their directors—in order to focus on the theater work she was doing. Maybe she specifically wanted to avoid discussion of her work with Ray and the natural segue into their tumultuous marriage and its even more tumultuous aftermath. Or maybe she was speaking the subjective or objective truth (or some amalgam).

But like it or not, Grahame was a regular auteur baby. Though never a major star (only a major minor one), with her offcenteredness, her combination of reflective cool (“It’s thinking”) and startling immediacy (who/where/what), she attracted more Pantheon directors than supernovas Davis or Crawford ever did. And even if those named above, plus studio-era craftsmen like Crossfire’s Edward Dmytryk and producer-directors like Cecil B. DeMille and Stanley Kramer, did little more than hire Grahame, let her follow her instincts, frame her (not, it seems, always an easy proposition) and shoot her, they’ve got to be given their due. Singly or collectively, they gave us a record of a talent that, upon reexamination, is emotionally wider and deeper and technically more accomplished than even I—a confirmed Grahame fan—first supposed.

Blonde Fever

Though L.A.-born, Grahame spent two years in theatrical road companies and on Broadway (including a stint understudying Miriam Hopkins, Tallulah Bankhead’s never-ill The Skin of Our Teeth replacement) before she signed an MGM contract in 1944. The story goes that MGM not only underused Grahame but didn’t know how to use her. In fact, most of the five films she did there between 1944 and 1947 combined the sirenish and comic modes that would later separate rather definitively in The Big Heat and Oklahoma! Trouble is, comic vamps are almost necessarily supporting roles—or were at post-Harlow, family-valuing Metro in the mid-Forties. So while Grahame’s debut role as the titular temperature raiser in the “B” Blonde Fever (44) and her marvelously stupid silent-screen temptress in Merton of the Movies (47) were fairly substantial, she had only 60 seconds of screentime as a flower-allergic flower-seller in the Tracy-Hepburn Without Love (45). But there were two looniest to RKO, the first to play Violet Bick, a more dimensional sister of her MGM comic sirens, in Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (46).

As Violet, one of the people whose lives would have been disastrously different had James Stewart’s George Bailey never lived, 22-year-old Grahame gives us, in seven snapshot-like scenes covering 17 years, the evolution of a flirt into a full-scale roundheels. In the early years, she is unrequitedly besotted with George, though capable of (comic) dudgeon after she discovers she’s ditched two good time Charlies to accept George’s offer of a platonic pastoral stroll. Later, as part of the group that sees off George and Mary (Donna Reed) on their honeymoon, Grahame brings her hand to her mouth in a touchingly ambiguous gesture. Does Violet feel joy for them? Sorrow for her single self? We don’t know. Later still, Grahame’s harrowingly electric as the wildly flailing, hoarsely shrieking, paddywagon-bound 35ish trollop of her 15-second had-George-never-lived (and given her a fresh-start loan) scene.

In late ’46 or early ’47, Grahame began “to work on her looks surgically,” according to Suicide Blonde, Vincent Curcio’s valuable biography of the actress. (That title is crazily apt, even though Grahame was only intermittently blonde and she neither committed nor drove anyone else to commit suicide, onscreen or off.) The surgical work, which continued over a decade, was mostly on her mouth, about which she was apparently very ambivalent. Curcio says that Grahame thought the ridges in her upper lip “too angular, too deep.” Yet she seemed to heed Diana Vreeland’s dictum about taking your worst flaw and painting it red, for in no way did the surgeries or the lacquering of the results normalize her mouth. To begin with, at least, Grahame found a highminded professional rationale for her self-alteration in Russian film theorist Lev Kuleshov’s belief that facial immobility was an asset in screen actors. Grahame, says a Curcio source, “had the [first] operation to make her lip more static.” She shows off the result in Crossfire, her second RKO loanout and a turning point in her career.

Crossfire

Grahame worked two days on Edward Dmytryk’s 20-day, $500,000 attack on anti-Semitism enveloped in a murder mystery, and she always considered the result—ten minutes of screentime, divided between two meaty scenes—her best work. In her first scene, Grahame, as a B-girl named Ginny, passes some professional Lime with a young soldier (George Cooper) wrongly suspected of murdering a Jew. She starts out perversely prickly when the soldier tells her she reminds him of his wife, folding tenderly into him while dancing, and inviting him to her place for spaghetti. In her second scene, being questioned about the encounter by homicide dick Robert Young, she does a dense, corkscrew figuration on her prickly-pliant spectrum. She goes from hostile-defensive (she’s especially affronted by the respectability of the soldier’s wife, played by Jacqueline White) to sympathetically helpful and even wistful (about the spaghetti she never got to cook) to, in a startling final twist, nastily shrewish.

If, as written, Ginny is a checklist of tough-tender noir-flooze conventions, Grahame’s sometimes measured, sometimes turn-on-a-dime emotional transitions shred the list. And they seem to come from somewhere other than a screenwriter’s Underwood. For heeding so well her dialogue director’s words about “thinking” and the who/where/what of her character (and, one would like to say, whatever idea Dmytryk had time to contribute), Grahame was nominated for a 1947 Oscar as Best Supporting Actress.

Having little way to exploit the noir talents Grahame showed in Crossfire, MGM freed her to sign a contract with noir-oriented RKO, in mid-1947. Within a year, RKO, fatefully, had her at work on the second lead, but the pivotal troublemaking character, in Nicholas Ray’s A Woman’s Secret (49).

A Woman's Secret

The film, Ray’s first after his stunning debut with They Live By Night, has many grace notes, but he didn’t want to do it and ultimately couldn’t overcome his lack of conviction, or the confusions of Herman J. Mankiewicz’s noir mystery/ love story/success saga/domestic comedy script. Still, A Woman’s Secret is a nice enough showcase for Grahame. She’s the songbird protegée of songbird manquée Maureen O’Hara and composer Melvyn Douglas, and rather interestingly she’s not ambitious, smooth, or practiced, as Mankiewicz frère’s Eve Harrington would be the next year. Instead, she’s a lazy, uncouth “natural” talent who’s more acted upon than active, but is no less able than Eve to screw up the lives of better, worldlier people. Grahame brings a feckless, prattling charm to the role; she makes self-involvement and moral idiocy deeply funny.

With a short first marriage to actor Stanley Clements already behind her, Grahame married Ray in June 1948 and bore him a son an eyebrow-raising five and a half months later. Then, on loan from RKO to Columbia, she played the lead in Ray’s In a Lonely Place (50). Whatever this movie started out to be, it became a haunting meditation on the transformative power of love and the final impossibility of love. With a dose of special pleading: Artists need more forgiveness for bad or crazy conduct, more love and trust, than ordinary mortals. As Curcio’s Suicide Blonde explains it, “Through Ray’s extensive rewriting the film paralleled the disintegration of [the Ray-Grahame] marriage, which began just as the cameras began to turn.” (The couple wouldn’t divorce until 1952.) Curcio adds that Ray once admitted in print that the film is not an objective account of his relationship with Grahame but “his perspective” on it.

So, early in her relationship with violent-tempered screenwriter Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart), Grahame’s Laurel Gray is self-possessed and even stately, a wryly tender comrade and a professional inspiration. Among other things, she inspires Steele to write the line, “I was born when she kissed me, I died when she left me, I lived a few weeks while she loved me.” Grahame has probably never projected a more attractive temperament onscreen. It’s a lighter, drier, less insolent version of Lauren Bacall’s in her pictures with Bogart (at one point Bacall was going to play the role) and a rebuke to those who thought or still think Grahame couldn’t do leads unless they were trampy, nasty, or nutty.

In a Lonely Place

Soon enough, Steele, who’s been a murder suspect all along, starts acting wacky to raise the trust issue, and much as the film may represent “his perspective,” Ray does right by Grahame as both character and actress. He provides her with a touching, and rare-for-her, opportunity to reach out to another female (Jeff Donnell, her real-life best female friend at the time); to play fuzzy panic as she accepts a marriage proposal from Bogart through a sleeping-pill hangover; and finally, after her foundationless distrust is revealed to Bogart and he leaves her forever, to reprise his earlier line, “I lived a few weeks while you loved me.” And to add: “Goodbye, Dix.” It’s one of cinema’s most moving farewells.

Under protest from Grahame, who cited the “great critical and popular acclaim” for her lead in Place in a telegram to RKO owner Howard Hughes, she was cast in a secondary role in Josef von Sternberg’s Robert Mitchum-Jane Russell vehicle Macao (52). No Shanghai Express (or even Shanghai Gesture), Macao is nonetheless an amusingly junky trifle, and Grahame’s seven-minute role counts as one of its assets. As a gambling-house dealer, she gels to toss off a few wisegal quips; wear an absurdly memorable gown whose jewel-encrusted sleeves terminate in gloves, also jewel-encrusted; and to share, for the first time, the screen with the very apposite Mitchum. Their characters never meet in Crossfire—though Mitchum was even then a quasi-in-law, his brother having married Grahame’s sister—and we want more of them together here. We want, especially, to know how come Grahame sacrifices self-interest to help Mitchum, who understandably asks: “Why are you doing this?” To Grahame’s credit, the sad-loser wistfulness she puts into her enigmatic nonanswer at least suggests possibilities.

As with MGM, Grahame’s best opportunities during her RKO contract were away from home base—not that she always got to seize them. Howard Hughes refused to loan her to Columbia for George Cukor’s Born Yesterday (July Holliday’s 1950 Oscar role) and to Paramount for George Stevens’ A Place in the Sun (51; Shelley Winters’ part). Winning her release from RKO after Macao, Grahame did Cecil B. DeMille’s The Greatest Show on Earth (52) as her first freelance picture.

Macao

The circus epic gave her a much larger portion of both wisegal quips and spangles than Macao (there’s a peerless hair-trigger rejoinder to Betty Hutton while they’re both bidenzed as ladies of Marie Antoinette’s court). Not to mention a breath-catching moment with an elephant—that’s really Grahame lying in the sawdust with the pachyderm’s foot poised above her face. Not to mention three men to inflame: roue aerialist Camel Wilde; elephant trainer Lyle Bettger, who turns vicious when refused her “little cat’s lips”; and stolid, on-hiatus-from-Hutton circus boss Charlton Heston.

Despite the hokey overbusyness of her character, Grahame is unique among the cast of DeMille’s idiotic Best Picture (!) Oscar-winner in suggesting an inner life (“thinking,” again). She suggests further that her good nature—as eroded and sparingly displayed as Hutton’s is bottomless and indiscriminate—is worth something. Projected through a tender stillness, it’s worth everything to the scene in which Grahame makes coffee for Heston and fills his pipe, unfreezing him as both character and actor for the only time in the movie.

In Sudden Fear (52), David Miller’s San Francisco-set, sub-Hitchcock, but somehow irresistible thriller, Grahame is the lover and partner-in-cons Jack Palance shunts aside after he marries older heiress-playwright Joan Crawford. Soon enough, Grahame, who’s most convincing as one of those low-born, cheap-souled noir pieces of work whose mastery of dress, speech, and manner allows access to polite circles, shows up at a party at Crawford’s Nob Hill mansion. Soon after that, Grahame and Palance are plotting Crawford’s death and a life of ease for themselves—that is, when Grahame isn’t goading Palance into rough sex and trying to hide her supremely satisfied, sly-puss smile at reconquering him by this pleasurable means.

The Greatest Show on Earth

In one of the few recorded instances of Grahame’s collaboration with a director, Miller told Curcio that she embraced his notion that her character was “earthy, not evil” and “the victim of scary sex with a scary man.” Interesting—if somewhat contradicted by the result. Best to let that result—the fullest exploitation of Grahame’s potential for perversity until that time—speak for its fascinating self.

Grahame’s fourth 1952 performance contrasts sharply with its antecedents of that year—or any year. In The Bad and the Beautiful, Vincente Minnelli’s silken, hotted-up Hollywood-on-Hollywood melodrama centering on an opportunistic producer (Kirk Douglas) and an alcoholic actress (Lana Turner), Grahame has a contrapuntal comic role. But the comedy doesn’t come from knowing wisecracks, as so often before; instead, it comes from the way she, as Rosemary Bartlow, carries herself in the world. She carries herself not just as a “lady,” but as a Modem Southern Belle, with all the conflicts between artifice and nature, genteel charm and shrewd calculation, self-delusion and self-awareness that type implies. Especially strong—and hugely funny—in her is the conflict between propriety and lubricity, as typified by her twice-repeated line to her hi story prof-turned-screenwriter husband (Dick Powell): “James Lee, you have a very naughty mind—I’m happy to say.” Yet much as Oscar voters love 180s, Grahame’s Best Supporting Actress win for The Bad and the Beautiful shouldn’t be taken only as a nod to her break with good-bad-girl roles. Her performance is a souffle—a teasingly sweet-tart raspberry souffle—that’s all the more delicious for seeming absolutely effortless. And Grahame has never been more endearingly, accessibly pretty onscreen. Thanks to inveterate prettifier Minnelli?

Grahame aroused high expectations in 1953 by teaming with performance-oriented Elia Kazan on Man on a Tightrope. Indeed, New York Times critic A.H. Weiler was not alone in finding her “excellent” as the disheveled, trollopy young wife of Communist-fleeing Czech circus owner Fredric March. But her Kazanian-naturalistic soiled-wrapper mussiness aside, I find nothing particularly riveting and something surprisingly generic in her performance. Part of the problem may rest in the generic quality of the writing by Robert E. Sherwood; Grahame gets very good value out of the script’s attempt to round and soften her character with a sympathetic, eleventh-hour response to her husband’s defiance of the Commies, but this development still seems like so much Dramaturgy 101.

The Big Heat

Later in ’53, Grahame played Debbie Marsh in Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat, the performance most cinephiles would choose for the time capsule. Debbie’s the dipsomaniacal, loose-cannon mistress of Vince Stone (Lee Marvin), chief henchman of the syndicate kingpin who controls a large Midwestern city. She’s vain, tauntingly flip with both Stone and his boss, jack-in-the-box kinetic—the last being Grahame’s own astute visual metaphor for Debbie’s instability, which drove Lang wild by forcing him to rethink staging and composition. When Debbie nies to pique Stone by flirting with the cop (Glenn Ford) bent on avenging the syndicate-engineered death of his wife, Stone scars one side of her face with a pot of scalding coffee.

After the scalding, Grahame takes Debbie through hysterical desperation, then bitter resignation (“I can always go through life sideways”), then poignant attempts at introspection (“Thinking’s pretty rough when you’ve spent most of your life not thinking”) and at establishing a human connection with the cop. Finally, Grahame makes Debbie terrifying as she exacts her revenge by killing evidence—withholding corrupt cop’s widow Jeanette Nolan (“We’re sisters under the mink”) and then scalding Stone, only to be shot by him. Her steely fervor gives a redemptive-cathartic moral grandeur to Debbie’s score-settling and takes the movie, until then an exemplary crime thriller, transcendently beyond genre. And she achieves real pathos in her death scene as, cradled by Ford in her prized mink, she gets a satisfactory answer to the question she asked earlier about his wife.

Reunited with Ford and Lang the next year, Grahame was “born to be BAD, to be KISSED, to make TROUBLE!”—or so said the ads for Human Desire. Lang’s version of Emile Zola’s novel La Bête humaine has a dank, prosy integrity, a relentless and, let’s say, beastly tawdriness and pessimism that’s very self-consistent. Yet I prefer the incongruously lyric and, let’s say, humanist 1938 Jean Renoir version of the book, which first shows the heroine (Simone Simon) at an open window stroking a kitten, to Lang’s, which first shows Grahame with her legs in the air—well, one of them, anyway. With this shot, Lang locks Grahame into a dreadfully misogynistic conception, and though she fits well into it and may even be central to it, there’s not much she can do to liberate herself from it. Not even when, early on, the script has her character trying to do right by her depressed, violent husband (Broderick Crawford); nor later when it tells us, plausibly enough, her only hope for freedom depends on getting her lover (Ford) to kill her husband.

Human Desire

Is Grahame nonetheless memorable in the role? Yes. There’s a wonderful ambiguity in her reading of “Most women are unhappy, they just pretend they aren’t,” which is either an attempt to manipulate Ford or a home truth or both. And she inspires real admiration for her fearless unconcern with losing audience sympathy as, step by step, she slips her character to its basest essence; the final step is a slut-special-nightmare from the universal male unconscious. Her look, on the other hand, is from a drag queen’s conscious deliberations about next Halloween: berets and hoop earrings and chevron brows and livid, pouty lips. This has to be one of those pictures on which Grahame tried to make her mouth more sensual by putting rolled Kleenex under her upper lip—only to have her male costar emerge from a kissing scene with a wet wad in his mouth.

All-star casts in adaptations of best-sellers or hit plays were one mid-Fifties antidote to TV’s bleeding of the movie audience, and in 1955 Grahame was part of three such enterprises. The first two to come out, both novel-derived, were Not as a Stranger, a raging box-office success, and The Cobweb, a flop.

The Cobweb, a nutty patients/nuttier staff mental-hospital drama, is ostensibly the more interesting because it reunited Grahame with Vincente Minnelli. But her performance—as Dr. Richard Widmark’s wife, who res pond s to hi s affair with Lauren Bacall by giving Charles Boyer the eye—has no particular impact because of the sheer number of nuts on board (including Lillian Gish and super-nut Oscar Levant). Unbelievably, Grahame fares better in Not as a Stranger, Stanley Kramer’s truly tedious making-of-a-doctor soap. Fast-forward 75 minutes-past 39-year-old Frank Sinatra as a med student—to see her as “the widow Lang,” a hard-drinking rich equestrienne who’s hot to trot with Olivia de Havilland’s country-doc husband Robert Mitchum. True, their seduction dance culminates in one of film history’s most famously bad scenes: As a stallion rears in his paddock and a mare whinnies interestedly in her barn, Mitchum’s heavy-lidded eyes take in Grahame’s kiss-me-or-kill-me mouth and then he crushes her to him very, you know, animalistically. Yet in their subsequent breakup scene, Grahame is miraculously small, true and somehow European—Signoret—or Moreau-like—in her ad but equable acceptance of what-must-be.

The Cobweb

In her third all-star-project-with-a-pedigree for ’55, Grahame played Ado Annie in Fred Zinnemann’s film of Rodgers & Hammerstein’s megasmash Broadway musical Oklahoma! Though Zinnemann never arrived at a unifying vision of the material, he was certainly wise to go along with R&H’s odd, astute first choice of Grahame for Annje. The choice was odd because Grahame was no singer—she’d been dubbed in A Woman’s Secret et al.—and here she would have to warble (piecemeal, in the event) two numbers, “I’m Just a Girl Who Cain’t Say No” and “All or Nothing.” And it was astute because Grahame delivers all the required comic broad strokes, plus a bonus crop of even more comic subtleties.

She plays the hoyden Annie’s brand-new attractiveness to men (especially cowpoke Gene Nelson and Persian peddler Eddie Albert) as a sometimes pleasurable, sometimes painful, always stupefying affliction. Grahame was always a witty physical actress—voluptuously scattered in The Big Heat, sveltely purposeful in Sudden Fear, skittishly graceful in The Bad and the Beautiful—and here she has Annie jouncing plumply in place. As much, it seems, in expectation (she resembles Mae West when another actor was talking and she was revving up to hit him with a zinger) a. to reassure herself the earth is still beneath her feel. And the childishly illustrative gestures Grahame uses to accompany her songs seem to express fickle Annie’s need to define and anchor a feeling before it gives way to another, contradictory one. Finally, let’s not overlook Grahame’s G-rated but unmistakable afterglow when she and Nelson ankle Shirley Jones’s wedding to Gordon MacRae—it’s a study in dippy delight.

Though Oklahoma! should have boosted Grahame considerably, her star began to dim shortly after the film’s release. She’d behaved badly on the set; her relationship with the press was in one of its contentious phases; and even critics were distracted by her greasy brown hair, greasy-suntan flesh tones and (of course) greasy crimson lips in her next movie, Ronald Neame’s British-made WWII espionage procedural The Man Who Never Was (56). Still and all, Grahame, as a Yank librarian in love with an RAF flyer, is genuinely affecting, particularly in the monologue where she pours her feelings for the absent airman into a “fictional” love letter she dictates for use in Clifton Webb’s spy plot.

The Man Who Never Was

Grahame, who had married film and TV writer Cy Howard in ’54, had a daughter by him in late ’56; took additional time off to settle “personal problems,” including splitting with Howard in early ’57; and returned, thuddingly, to movies later that year with the “B” Western Ride Out for Revenge. Then, after almost two years of inactivity, she wound up the Fifties—her decade—with a fleeting return to the “A”’s: Odds Against Tomorrow would be her last studio picture for twenty years.

In Robert Wise’s determinedly arty bank-robbery thriller, Grahame is the loopy neighbor of ex-con Robert Ryan. When Ryan reneges on a promise to babysit her child, she runs a considerable gamut spanning annoyance at Ryan’s no-show, concern for her temporarily unattended infant, flirtatiousness, and finally a pervy-erotic fascination with murder (“How did it feel … when you killed that man?”). That’s altogether too much for a four-minute part, but Grahame’s a past master of the pervy-erotic stuff (so’s Ryan), which here is expressed with the eye giant close-up rather than the mouth.

Whatever salutary effects Odds might have had on Grahame’s career were nullified by her marriage, in May 1960, at age 36, to 23-year-old Tony Ray, Nicholas Ray’s son by a pre-Grahame union. The marriage was the Woody-Mia-Soon Yi story of its relatively prim time, and press accounts never failed to mention that Tony Ray was now stepfather to his 11-year-old half-brother, Nicholas’s and Gloria’s son. The union with Tony Ray would last 15 years and produce two sons, half-brothers to their father’s half-brother-become-stepson. Amazingly, in all this there is no incest in the sense of consanguine sexuality. But it was way too weird to fly with the public and the studios, and so, for the rest of her life, Grahame was forced to do what she could to nourish her body and soul.

Chilly Scenes of Winter

The body part was taken care of by TV series guest shots, MOWs, the miniseries Rich Man, Poor Man; low-budget features with titles like Mama’s Dirty Girls and Mansion of the Doomed; and stock productions of farces like The Little Hut and The Marriage-Go-Round. As for the soul part, she studied with both Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler and realized a long-held ambition to be a serious, even classical stage actress. Over the years, in the U.S. and England, she appeared in The Time of Your Life with Henry Fonda, The Glass Menagerie (as Amanda), Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (Martha), The Merry Wives of Windsor (Mistress Page), and Macbeth. She usually won admiring notices for aspects—rarely the entirety—of her performances, possibly because she remained difficult to direct in the new medium, and certainly difficult to commit to fixed blocking. She even, finally, made a couple of classy studio movies.

As John Heard’s burdensomely dotty mother in Joan Micklin Silver’s Chilly Scenes of Winter (79, aka Head Over Heels), Grahame does what she must—like take huge doses of laxatives and repair to her bathtub, invite guests to dinner and fail to provide food—but like the film itself, she’s never as piquant as she’s supposed to be. She’s best in her one lucid scene, in which, her voice cracking, she recalls Heard’s father’s heart attack death at age 39, on a bus.

Grahame’s final movie fittingly returned her to the auteur league of her heyday. In Jonathan Demme’s Melvin and Howard (80, and getting better with each passing year), she’s Mary Steenburgen’s mother, and because her role was reduced in the final cut, she’s less a character than a thread in the film’s densely woven tapestry of lower-middle-class life. But even with next to no dialogue, she puts across the point—with a stiff carriage and skeptical glances—that she doesn’t think much of her daughter’s spouse (Paul LeMat, as the would-be heir of one-time Grahame nemesis Howard Hughes).

In September 1981, while in England to rehearse her second go at The Glass Menagerie, Grahame was felled by a flare-up of the cancer she’d held at bay for several years. After a slapstick-tragic stay at the Liverpool family home of actor/ex-lover Peter Turner (the events of which comprise his memoir Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool), her family brought her to New York, where she died in October.

It’s interesting, if ultimately depressing, to speculate on what Grahame might have done in films had the collision of her private life and the zeitgeist not wrecked her career in 1960. She could have had a triumph as Charlotte Haze in Lolita (not that I have any complaints about Shelley Winters’s Charlotte), she could have done well as Tuesday Weld’s mother in Pretty Poison (again, no complaints about Beverly Garland), she could have played Tuesday Weld’s mother in anything. And if she’d lived a little longer, surely David Lynch would have found—or created—something for her to do. But failing all that, what she did was plenty. And whether she was self-directed, mother-directed, auteur-directed, or all three, the uses of her perversity were many and most often sweet.