Home Is Straight Ahead

This article appeared in the February 2, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

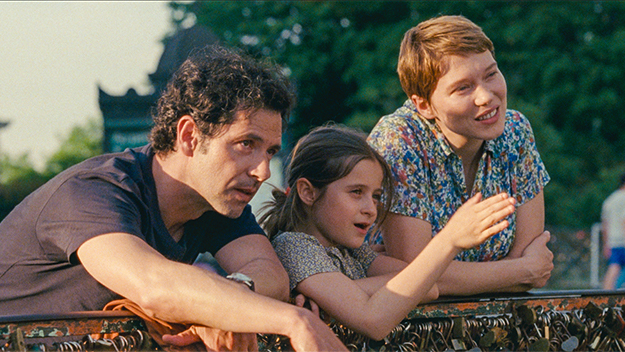

One Fine Morning (Mia Hansen-Løve, 2023). Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics.

About a third of the way into One Fine Morning, the luminous new feature from Mia Hansen-Løve, Léa Seydoux’s Sandra is shown in the throes of a dream, her sleeping face under superimposed images of a quicksilver seal twirling in a murky sea. The animal spins and then turns suddenly toward the camera, snapping open its jaws and propelling toward the lens, just as Sandra snaps awake. The dream has become a nightmare, and the friendly creature a threat.

There are many ways one could interpret Sandra’s dream. It might be an omen of both her attraction to her soon-to-be-lover, Clément (Melvil Poupaud), who has just told her a tall tale about a “sea leopard,” and the emotional violence their relationship will eventually inflict on their lives. There is also the fact that Sandra has just moved her father, Georg (Pascal Greggory), a former philosophy professor with a neurodegenerative condition that is fast eroding his cognitive capacities, into an assisted-living facility. As anyone who’s been in this situation will know, a parent’s decline (to say nothing of the appalling conditions of most eldercare centers, on full display here) is an overwhelming confrontation with mortality, sometimes more unfathomable even than one’s own. Does the sea leopard represent the thrill of new life—and its attendant tingle of danger—or the end of an old, familiar, beloved one?

This dream scene is the only instance of overt subjectivity in a movie that otherwise hews to an objective, third-person perspective—one that calls back to the deceptive simplicity of the “Comedies and Proverbs” series by Éric Rohmer, whose influence is also invoked by the casting of Greggory (a regular presence in Rohmer’s ’80s and ’90s movies). One Fine Morning eschews the matryoshka-doll meta-narrative of Hansen-Løve’s previous film, Bergman Island (2021), and the sudden tonal and temporal shifts of earlier, similarly themed works like All Is Forgiven (2007) and Father of My Children (2009); it instead returns to the linear structure of 2016’s Things to Come. The film charts a year in the life of Sandra, a young widow and single mother, following her from one summer to another, as she grapples with impending grief and incipient love. Her father used to be “obsessed with rigor and clarity,” as one character notes; now he can neither think rigorously nor see clearly, thanks to his fast-progressing Benson’s syndrome. Sandra, her sister (Sarah Le Picard), and their mother (Nicole Garcia) are forced to move him out of his book-lined apartment and into a series of increasingly depressing nursing homes. At the same time, Sandra begins a capricious affair with Clément, a married “cosmochemist.”

The film’s binary structural and thematic framework, not to mention its auroral title, recalls a line from Walden: “In any weather, at any hour of the day or night, I have been anxious to improve the nick of time, and notch it on my stick too; to stand on the meeting of two eternities, the past and the future, which is precisely the present moment; to toe that line.” Even as the film flows along its two major storylines, it frequently diverges into little rivulets of daily life, allowing the present moment to breathe and bloom, and capturing the indeterminacy of real life with rare, preternatural precision As it unfolds, we are initiated into the rhythms of Sandra’s everyday existence: we see her working as a translator for visiting American World War II veterans; picking up her daughter, Linn (Camille Leban Martins) from school; watching the obnoxious kids’ movies that Linn likes; and visiting her sister’s house for Christmas. Sandra and Linn live together in a cramped one-bedroom apartment in which neither has any space to themselves. Sandra’s responsibilities to her relatives, both old and young, preclude much of an inner life and make completing her personal project—translating Annemarie Schwarzenbach’s aptly titled 1939-40 travel journal, Where Is the Promised Land?—seem like a distant dream.

In a Film Comment interview with my colleague Devika Girish at Cannes last year, the director explained the resonance of the film’s French title: “when we say ‘un beau matin,’ we see light.” Morning also implies night, both bygone and to come, and though One Fine Morning is certainly radiant, it also doesn’t avoid the dark. The opening shot shows Sandra on a beautiful summer morning, striding alone down the shaded side of a Paris street to visit her ailing father, the shadows blinding her to the beauty around her. In the final scene, Sandra gazes upon the city with Clément and Linn, standing in the light and the promise of a new life as Clément points out over Paris and says to Linn, “Your home is straight ahead.”

The performances—of Seydoux and Greggory in particular—ground the film in specific behaviors, even as Hansen-Løve deftly navigates a story that could easily drift into sentimentality. Seydoux is a quiet marvel, her eyes flickering between childlike vulnerability and heart-wrenching resolve. As Georg, Greggory’s perpetually hunched back and halting, searching line readings belie a lifetime spent thinking, teaching, and writing. Minor characters gesture at the vast complexities of life beyond the borders of screen. In a brief scene early in the film, Sandra brings Linn to visit the child’s great-grandmother, whose mind is still sharp even though her body is deteriorating fast. She tells them about her daily life before declaring, “It’s a bit difficult at times… living. You mustn’t let people take pity on you. You must show that you’re there, a living person. Pity, forget that. Never accept pity.” Her words distill Hansen-Løve’s approach to her characters. One might assume that this compassion and attention are the result of the story’s basis in autobiography—One Fine Morning draws from the filmmaker’s own experiences of her father’s illness and death—but I’m not sure it’s so easy to see one’s family, or oneself, with such clarity and respect. Hansen-Løve’s achievement here goes beyond simple memoir; it’s an act of illumination.

Clinton Krute is the Co-Deputy Editor of Film Comment Magazine.