Hail, Caesar! + Illusions

Hail, Caesar!

Films about filmmaking very often tell the same story with the same characters: creative types are highly temperamental and have volatile, complicated personal lives, and there’s one man in the center who’s responsible for keeping things together. They’re so uniform in this regard that a beginning filmmaker could probably write/direct a version of the genre as their very first feature and it would be credible—even though these narratives are supposed to draw on years of hard-won experience in the biz. Such a feat isn’t so different from what the Coens have done with Hail, Caesar!, which applies this classic story arc (or maybe it’s that other old formula, The Odyssey) to a film production environment which neither brother has experienced firsthand—a Golden Age studio. Along with its expert telling, what makes Hail Caesar! so enjoyable is how the Coens reconfigure the history of the Big Eight. In the world of their film, screenwriters brag about how much Communist subtext they’ve put in their scripts; a high society drama is being shot in black and white by an Olivier-esque director, even though we’re well into the Technicolor Fifties; Hobie Doyle, a young western star undergoing a radical image makeover, is set up on a date with a Carmen Miranda type named Carlotta Valdes (aka the Spanish-American woman possessing “Madeline” in Vertigo); and rather than being a violent, glorified goon, studio fixer Eddie Mannix is a man of deep faith.

However, some have criticized the film for omitting minorities in this half-fantastical milieu. (Save for some extras at a Chinese restaurant and Ms. Valdes, the entire cast is white.) When asked about this absence in an interview with The Daily Beast, Joel Coen replied: “I don’t understand where the question comes from. Not why people want more diversity—why they would single out a particular movie and say, ‘Why aren’t there black or Chinese or Martians in this movie? What’s going on?’ That’s the question I don’t understand. The person who asks that question has to come in the room and explain it to me.” When asked a follow-up question about whether or not it’s important to consciously factor in diversity when writing, Ethan Coen stated: “Not in the least! It’s important to tell the story you’re telling in the right way, which might involve black people or people of whatever heritage or ethnicity—or it might not.”

Hail, Caesar!

Unsurprisingly, these responses attracted more opprobrium than what the original complaints reflected. It’s valid to take a stand against tokenism; on the other hand, it’s unwise to use a phrase as loaded as “telling in the right way.” (And including “Martians” on a fake laundry list of races is just about the pinnacle of unartful.) But more pressingly, the underlying premise behind the Coens’ answers is wrongheaded: they’re speaking as if no Black, Latino, Native American, Middle Eastern, or Asian people ever worked below-the-line jobs or in front of the camera, when in fact they had. There is no such thing as “injecting” diversity into an industry that’s had it from the start. The slipperiness of golden-age diversity is typified by Carmen Miranda: born in Portugal, she became famous by performing Bahian sambas, which erased their blackness and made them palatable to white Brazilians; when she made the jump to Hollywood, largely thanks to the United States’ “Good Neighbor Policy,” she was harshly criticized for homogenizing and misrepresenting Latin America. Despite the Coens’ eagerness otherwise to make pastiches and parodies of classical Hollywood, their statements require taking Hollywood’s fictions at face value, contrary to the multiple peeks behind the curtain that Hail, Caesar! offers. Furthermore, since their new film is a work of fiction that delights in embellishing upon history, there’s no reason not to invent more than one non-white character who’s just trying to get by in the manic microcosm of Capitol Pictures—except out of personal preference. It’s the story you choose to tell; “right” doesn’t enter into it.

While watching DeeAnna Moran (Scarlett Johansson) perform her big, aquatic Busby Berkeley number (and its fallout), I expected that Eddie Mannix would next pay a visit to whoever actually sang the tune she lip-synched to. (As DeeAnna’s nasally, Noo Yawk speaking voice makes clear, it was clearly not a recording of her.) But unlike Singin’ in the Rain, I imagined that the real singer we’d see would be a black woman, because we live in an era where we can be honest about these things—which is to say, I was thinking of something along the lines of Julie Dash’s Illusions (82). Like Hail, Caesar!, Dash’s film is also a work of fantasy and revision inside a Classical Hollywood studio. Set in 1942, Illusions tells the story of Mignon Dupree (Lonette McKee), a light-skinned black woman who’s passing for white and works as a studio executive. Dash makes a point to show that Mignon’s position of power isn’t all glamour or cigar-chomping bravura: an Army lieutenant in charge of ensuring pictures have pro-military messages aggressively hits on her, and near the end of the film, even rifles through her desk and papers, discovering that she’s been passing. Her main work-related problem is to have Ester Jeeter (Rosanne Katon), a black singer, re-record a track for a big musical that went out of synch during shooting. (As it stands, the white actress on screen, in Mignon’s memorable phrase, “looks like she’s chewing marbles.”)

Illusions

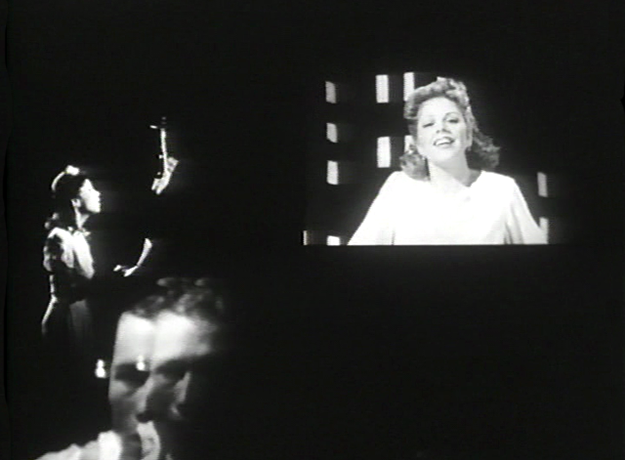

The film’s most indelible image is of Ester, standing in the dark void of the recording booth illuminated only by the footage of the lip-synching actress screening in front of her, with the reflection of the (white, male) sound engineers visible in the booth’s window. These separate visual planes of depth underscore the distance (physical, racial, sex) between these three characters, and between illusion and reality. While the white star passively lies around her plush, (fake) penthouse apartment, Ester smiles widely as she sings, moving in time to the rhythm; later, she’ll admit to Mignon she was nervous, but here it doesn’t show. Of course, the actress playing Ester is lip-synching to an Ella Fitzgerald song, an instantly recognizable and famous voice, which adds yet another layer of performance and illusion to the scene.

After completing the dub and effectively saving the movie, Mignon arranges to give Ester a bonus despite protestations from her boss—a pointedly tight-fisted gesture from a studio making millions of dollars a year, commenting upon the pay gap between sexes and races. (Even now, at least as of 2014, black women were paid 63 percent of what white men were.) Ester chats with Mignon in front of an office full of white secretaries in an overly familiar way that threatens her position, going as far to say “it’s nice to have someone on the inside.” But it’s as if they don’t hear what Ester is saying; deep inside this factory that manufactures dreams and fantasies only for whites, she retains a degree of invisibility from the performance she just faked. (Ester is also quick to reassure Mignon of her incognito status: “Don’t worry! They can’t tell like we can.”) After Ester leaves, one secretary compliments Mignon on her ability to engage with black talent. “How are you so good with them?” she asks. Mignon responds: “It’s simple Louise: just speak as you would speak to me.” (While the irony of her advice to this stand-in for the industry should be obvious, it’s not yet been taken.)

Illusions

Dash’s vision of this ideal woman who never was is not mere wish fulfillment, but rather a thought experiment: what conditions would allow her to exist, and what would her challenges be? Through Mignon’s voiceover, which seems to exist somewhere between the present and past, between an imagined listener and internal monologue, Dash lays out the invisible history behind Hollywood’s image-making while also offering an alternative approach to it: one that is inclusive, and not dutiful but dazzling.