Beyond Representation: An Interview with Genevieve Yue

This article appeared in the June 10 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

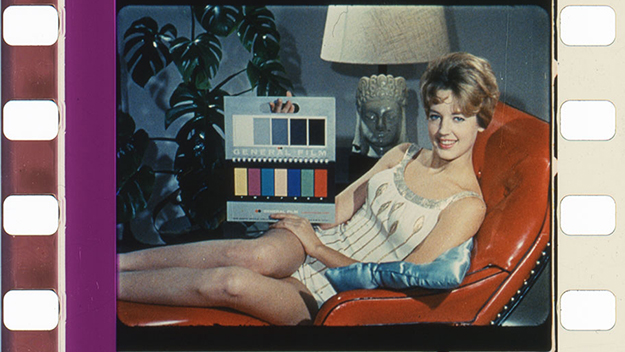

In Girl Head: Feminism and Film Materiality, critic and theorist Genevieve Yue looks beyond the film image to explore the feminist implications of the film object itself—of its emulsion and base, spliced edits, and laboratory printing. Yue opens her book with a discussion of the China Girl, also known as the “leader lady” or “girl head”: an image of a smiling, typically white woman attached to the beginning or end of a film reel as a gauge for color timing and setting tone density. China Girls are rarely glimpsed by the audience but remain with the print throughout its life. Their racialized name is a cipher—it holds no meaning, or if it ever did, it is no longer remembered.

Using these leader ladies as a jumping-off point, Yue locates and describes a common motif in laboratory, editing, and archival practices: the disappearance of the female body. Girl Head tracks this theme from the films of illusionist Georges Méliès, in which women are made to vanish “on camera,” to contemporary works of both avant-garde (Barbara Hammer’s Sanctus) and popular cinema (David Fincher’s Gone Girl) where a woman’s disappearance is central to the form and function of the film.

With the introduction of the LAD (laboratory aim density) system in the mid-1970s, and the growing awareness of the problematic, one-size-fits-all nature of using white faces for color timing, China Girls are, as you mention in your book, now fairly obsolete and arbitrary. But they’ve managed to retain an aggrandized mythology. Where do you think their appeal comes from?

In my research, I found the question of the utility of the China Girl image really interesting, because even though it wasn’t terribly useful, it still sticks around. This isn’t part of some nefarious patriarchal scheme—there was no historical necessity for a reference image to take the form of a white woman, in close-up, surrounded by blocks of black, white, and gray, but that’s what happened. Still, there are a lot of weird and wonderful variations among the China Girls that I’ve seen. On one hand, you have the industrial standards that the labs are meant to provide, and on the other, the creative ways that individual labs found to meet those demands. Before Kodak and other film manufacturers began producing their own reference images in the 1970s, laboratories usually made their own, so there’s a lot of variety and eccentricity to the form, which I enjoy.

But the common form of the China Girl image endured (I think probably haphazardly) in large part because laboratory culture is relatively closed. It’s highly skilled blue-collar work, meaning someone has to invest a number of years to even learn how to use the equipment, let alone do it well. Labs would have maybe a dozen employees, most of them white men (a lot of them seemed to be named Steve!), and there wasn’t a lot of turnover. So the internal workplace culture, like any tight-knit group, was slow to change. We’re in a situation now where there are only a couple of commercial labs operating in the U.S., and there’s a lot of knowledge that is lost when technicians retire or are laid off. That’s not a history that has really been recorded, and I think that’s a shame for anyone who cares about film as film.

What was your introduction to China Girls? What interested you in that history?

My own interest in China Girls began when I first saw Morgan Fisher’s Standard Gauge (1984), which features a section on China Girls, and which has since become one of my favorite films. Around that same time I participated in a workshop that Tom Gunning organized at the Getty Research Institute, where Mark Toscano, an archivist at the Academy Film Archive, brought a reel of China Girl images to screen. He threaded the reel on a 16mm projector and let it run. It was really amazing: a few silent minutes of a woman sitting, evidently being told to smile. I had almost certainly seen this woman before—when a projectionist missed a changeover cue during a screening, for example—but hadn’t really registered it. I really wouldn’t have begun to consider [the implications of] this image with having first been steeped in feminist film theory. Only then was it more than a curiosity—something meaningful, something that could yield new knowledge about the film medium.

The omnipresence of China Girls in labs and archives also makes me wonder how you approached this research. Apart from locating avant-garde works like Standard Gauge and Toscano’s Releasing Human Energies [both of which make explicit use of the China Girl], what was your process in searching for and looking at these images?

I learned a lot by talking with lab technicians. I got to know people at DuArt, Cineric, Technicolor, former Kodak employees, folks at the Rochester Institute of Technology, and people at the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. All of them were so generous. Even within these highly technical spaces, there’s so much knowledge that is transmitted vernacularly. It’s not written down anywhere, but it has seeped into the culture of lab work. The China Girl was one of those things that drew people’s attention but only behind the scenes. When lab people found out that I was working on this project, they were often really excited to share their stories with me. But there was also a lot of mystery. No one seemed to know the origins of the term “China Girl.”

In your description of the use of feminist film theory in the archive, you caution against viewing gender as something that is “forever retreating” and in need of being excavated and “restored to the scholarly record.” Instead, you wish to “patiently observe the scenes of [women’s] disappearance.” Could you talk a bit about that distinction and what it means to observe disappearance in an archive?

Feminism has that temptation, too. There’s a great essay by Jane Gaines, “On Not Narrating the History of Feminism and Film,” that describes how feminist theory gets worked up about retrieving lost women, even after many such figures have been found by historians. To some extent feminist film theory is organized around this sense of loss, and so runs the risk of obscuring the objects and figures it examines. This is very much what the film archive chapter of my book is about—the obsessive attempt to find traces of a lost woman, which in turn motivates the construction and accumulation of stuff in the archive.

While reading the section on avant-garde films, it occured to me that many of the women-directed experimental works you talk about which deal with materiality—works by Lynn Hershman Leeson, Valie Export, and Beatrice Gibson, for example—are ironically less likely to be preserved and restored. I’m thinking of something like Jennifer Montgomery’s Transitional Objects, which is explicitly about the transition from analog to digital and shows the filmmaker performing film work. As a huge Montgomery fan, I’ve only ever been able to see her work on shoddy VHS transfers.

In some ways this has been the story of film more generally: an “invention without a future” that is regarded as always being in danger of disappearing. In the archives chapter, I discuss Bill Morrison’s The Film of Her, which is about the Paper Print Collection [a collection of 6000 films made between 1894 and 1912] at the Library of Congress, apparently discovered in 1942 the day before it was to be incinerated. Decisions about what gets made, saved, preserved, and circulated are far more haphazard and contingent than carefully orchestrated, and that can leave you feeling anxious about films crumbling out of existence. But mourning the death of cinema is premature, I think—or at least it’s a shortsighted view of what the medium is and can be.

The book also delves into what you refer to as “escamontage,” or using effects editing to remove women’s bodies from film. Were there specific films that spurred this connection between leader ladies and diegetic instances of disembodied women? When I started reading Girl Head I had coincidentally just watched Jane Campion’s In the Cut for the first time, and then I went down the rabbit hole of Julia Kristeva’s writing on beheading, which touches upon the Medusa myth and Mary, Queen of Scots.

In an earlier version of the book, I had gone down a similar rabbit hole of headless women. Most of that didn’t make it into the final version, because it was pulling me too much into the realm of cinematic representation, which I was trying to avoid. I also didn’t want to sensationalize the violence any more than was already apparent. But if you read between the lines, you’ll notice that the book is filled with female figures who have been cut, disappeared, or killed. My goal was to understand how women, and women’s bodies, had been used within film production spaces, and how they themselves had been made productive under patriarchal conditions. Rather than dwelling on the horror of the decapitation of Mary, Queen of Scots [visualized by Thomas Edison in 1895’s The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots using an early example of a trick cut], I wanted to know what kind of work that violent act was accomplishing for film editing practice, and whether that was perceptible at the level of the splice. It is straightforward enough to condemn the spectacle of a woman’s beheading as misogynist, but the challenge I gave to myself was to step outside the realm of representation to see if I could find the same logics of patriarchal power in non-representational spaces like the film lab, the editing bay, and the film archive. I’m both satisfied with and dismayed by the results, because I found that those pernicious structures hold all the way down. But I’d rather know the full extent of the problem than not. If there’s to be substantive change to the ways movies are made, it has to go beyond “representations of”–type issues to the pervasive inequities that are less apparent but nonetheless deeply embedded in ordinary production practices.

Girl Head: Feminism and Film Materiality is available from Fordham University Press.

Mackenzie Lukenbill is an audiovisual archivist and editor and a Digital Archive Assistant at Film Comment.