By Nick Pinkerton in the March-April 2018 Issue

Totally Wired

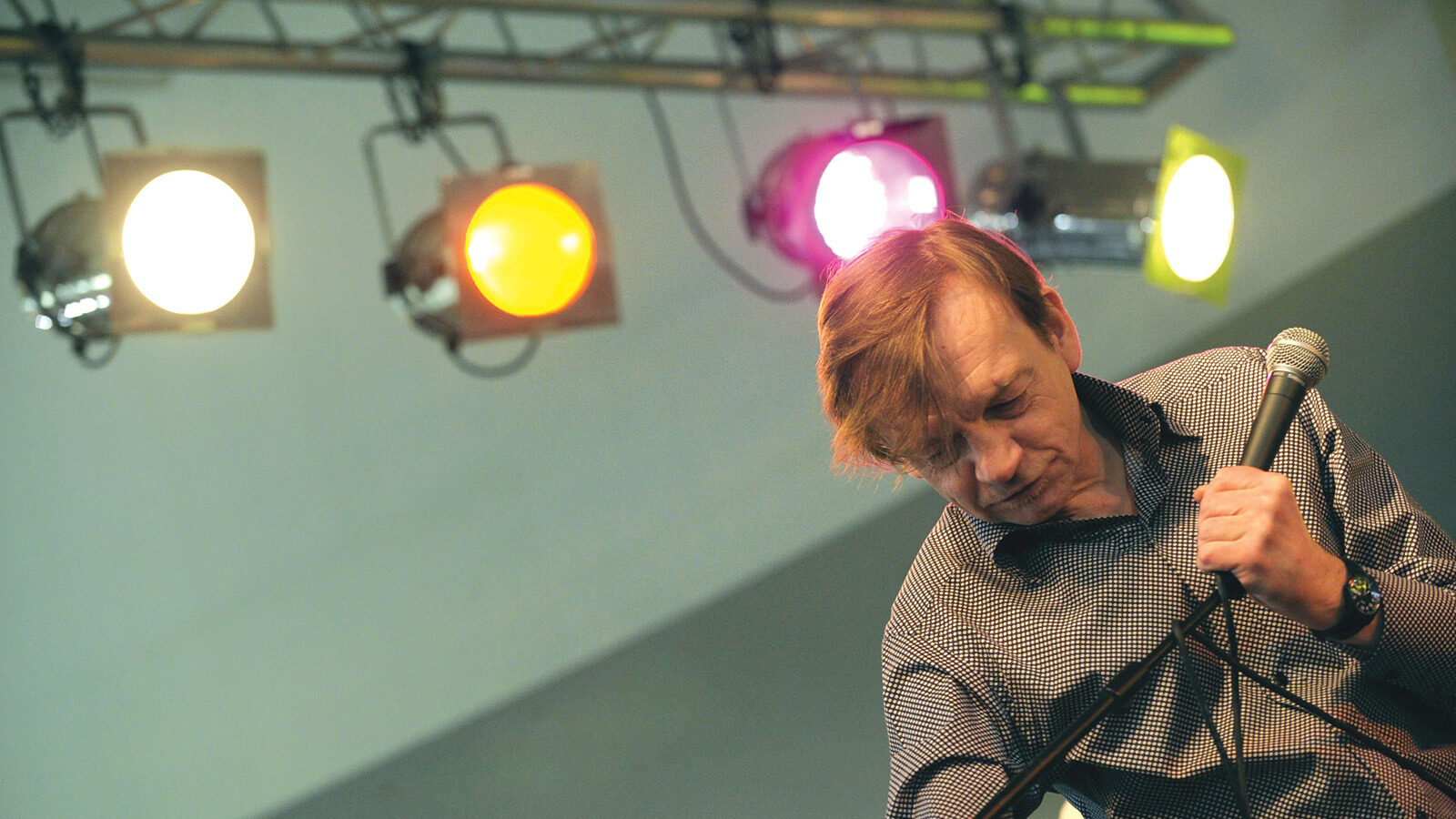

Though his contributions to film were few, Mark E. Smith, late front man of the cult British band The Fall, had a career that could be called distinctly, grungily cinematic

To quantify the late Mark E. Smith’s direct impact on cinema doesn’t take more than a paragraph. Two songs by his band of over 40 years, The Fall, appear as bumpers to high-profile feature films—“Hip Priest” in Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and “Industrial Estate,” nonsensically, in Ben Wheatley’s awful adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise (2015). Smith was purportedly contracted to contribute a song to the soundtrack of Twilight (2008), but the results went unused. (“They said they’d give us $50,000 to come up with a song. So I said, I’ll give them some horror…”) He had a handful of film cameos on his résumé, too—appearing as his middle-aged self in the Manchester of his youth in Michael Winterbottom’s 24 Hour Party People (2002), and giving a blank-verse mock interview in Charles Atlas’s fractured, Fall-soundtracked “docufantasy” hybrid starring dancer/choreographer Michael Clark’s company, 1987’s Hail the New Puritan, beginning his screed: “The refusal of genius to fulfill its destiny has been a problem of mankind’s since 1911…”

From the March-April 2018 Issue

Also in this issue

It is more productive, perhaps, to ask what impact the cinema may have had on the art of Mark E. Smith, a question that calls for some deep excavation. Smith’s gnomic lyrics were a dense decoupage of references to antiquity and idiomatic slang and occult texts, to footballers and politicians and television presenters, inscrutable sci-fi lingo, comic magazines, overheard pub chat, late-night Twilight Zone reruns and game shows and mysterious initialisms and, yes, the occasional cinematic allusion. He would’ve likely goggled at being called a “curator,” but the sundry bits of material that caught in the sieve of his imagination together amounted to the Fall aesthetic, at the heart of it a small individuated canon—the music of the Seeds and Link Wray and Can, the weird fiction of Arthur Machen and H.P. Lovecraft and Fritz Leiber—that changed little through years of interviews.

Smith’s 2008 book Renegade, a free-associative wander through his autobiography with doggerel “tales” stuffed in its crevices, ends with the author drawing a curious comparison between his own creative approach and that of another profligate raconteur, Orson Welles. In a typically cracked, piss-taking tribute, Smith breezes through his appreciation of Welles’s films, lingering instead on outtakes of the Magnificent Ambersons director’s degrading for-hire work as a pitchman for “fishfinger and processed-pea commercials.”

“The funniest part of it is that he can’t read the script,” wrote Smith. “He needs to know the thread of the story. And he keeps asking questions like ‘Who wrote this?’ and ‘How do the fish get into the fingers?’—he’s obviously drunk and can’t grasp the fundamentals behind it… He was in another zone. Telling stories on stories until in the end he himself is a story. He didn’t seem afraid of living in that world; and it’s childish in a way, but when you can deal with it and use it, the results are evident.”

A valentine from one genuine one-off to another. The aspect of self-portraiture is clear here; in a 2011 interview Smith named Welles as one choice to play him in a biographical film—an answer changed in a later interview to Rip Torn, incorrectly presumed to be dead. If we want to carry the Welles-Smith comparison further we might note that the former radio actor and the frontman with the declamatory delivery were unparalleled in their respective art forms in the attention they gave to the voice and qualities of cadence—through the long lifespan of The Fall, during which time 60-some members passed through the band’s ranks, Smith’s spoken, slurred, and occasionally squalled delivery was the foundational rhythm instrument on which The Fall’s sound was built.

A valentine from one genuine one-off to another. The aspect of self-portraiture is clear here; in a 2011 interview Smith named Welles as one choice to play him in a biographical film—an answer changed in a later interview to Rip Torn, incorrectly presumed to be dead. If we want to carry the Welles-Smith comparison further we might note that the former radio actor and the frontman with the declamatory delivery were unparalleled in their respective art forms in the attention they gave to the voice and qualities of cadence—through the long lifespan of The Fall, during which time 60-some members passed through the band’s ranks, Smith’s spoken, slurred, and occasionally squalled delivery was the foundational rhythm instrument on which The Fall’s sound was built.

As well-read as crooner-cum-novelist-and-screenwriter Nick Cave, and not even fractionally as annoying about it, Smith occasionally hinted at ambitions outside of rock. He wrote the music for the Michael Clark & Company ballet “I Am Curious, Orange,” which became the 1988 album I Am Kurious Oranj, these titles a play on the 1960s erotic avant-garde films of Swede Vilgot Sjöman. In Renegade, Smith expressed a desire to write a British film “on a par with Dead of Night”—Ealing Studios’s 1945 anthology horror film—but the workload he took on in touring and recording was already astonishing for a man of his notorious drug and alcohol intake, and any such ideas were put to rest with Smith, who died in January at his home in Prestwich, aged 60.

In Smith’s final interview, he told The Guardian that he hated all screen adaptations of Philip K. Dick, save for Paul Verhoeven’s 1990 Total Recall (“Arnie gets it”). Such bits of tossed-off film criticism pepper his interviews, as well as Renegade, which abounds with recollections and observations relating to the movies. Smith remembers going with his father to Whitefield to see the premiere of Cy Endfield’s Zulu (1964), in which James Booth plays a distant family relation who was a veteran of the Battle of Rorke’s Drift. (“I’m going, ‘Dad, which one are we related to?’ And there he is laid up in bed; on the skive with a boil on his arse.”) Shortly thereafter he writes, “He was seriously worried about it, people staring at this big monkey that didn’t even look real,” while recalling his grandfather’s curious vendetta against Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack’s King Kong (1933). And throughout there are the snap judgments, on 1999’s The Blair Witch Project (“a home movie”), Patrick McGoohan’s 1967-68 miniseries The Prisoner (“proper writing”), Gus Van Sant’s Last Days (“You can see how [the Cobain-esque protagonist] was driven crackers by his mad wife and his flimsy mates”) and Walk the Line (both 2005), and rock biopics in general (“It’s all about people, Hollywood people mostly, who just want to attach themselves to this type of character; cool by association”).

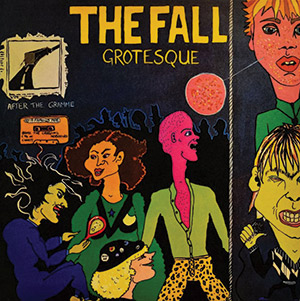

The Hammer Horror films are another recurring touchstone. Smith scholars, second only to Joyceans in the rigor of their research, have identified the origin of the line “And will forever end this reign of terror…” in “Home Before the Moon Falls” from 1979’s Dragnet to Terence Fisher’s 1958 Dracula. Other cinematic references are less obtuse. “Frightened,” the leadoff song on the first Fall LP, 1979’s Live at the Witch Trials—a crawling, trawling account of urban paranoia and isolation—is written from the first-person perspective of a Travis Bickle–esque cinema squatter who announces, not without a hint of menace, “I’ll appear at midnight when the films close.” “New Face in Hell,” a track from 1980’s Grotesque (After the Gramme), takes its title from the U.K. re-release of a largely forgotten 1968 George Peppard private eye vehicle from Universal, known stateside as P.J. On “Mere Pseud Mag. Ed.,” from Hex Enduction Hour, an album partly recorded in a cinema in Hitchin, Hertsfordshire, we get sideswipes at The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and, of all things, Mel Brooks’s History of the World: Part I (1981). On 1983’s Perverted by Language, in “Garden,” Smith coins the particularly withering insult: “That person is films on TV / five years back.”

The Hammer Horror films are another recurring touchstone. Smith scholars, second only to Joyceans in the rigor of their research, have identified the origin of the line “And will forever end this reign of terror…” in “Home Before the Moon Falls” from 1979’s Dragnet to Terence Fisher’s 1958 Dracula. Other cinematic references are less obtuse. “Frightened,” the leadoff song on the first Fall LP, 1979’s Live at the Witch Trials—a crawling, trawling account of urban paranoia and isolation—is written from the first-person perspective of a Travis Bickle–esque cinema squatter who announces, not without a hint of menace, “I’ll appear at midnight when the films close.” “New Face in Hell,” a track from 1980’s Grotesque (After the Gramme), takes its title from the U.K. re-release of a largely forgotten 1968 George Peppard private eye vehicle from Universal, known stateside as P.J. On “Mere Pseud Mag. Ed.,” from Hex Enduction Hour, an album partly recorded in a cinema in Hitchin, Hertsfordshire, we get sideswipes at The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and, of all things, Mel Brooks’s History of the World: Part I (1981). On 1983’s Perverted by Language, in “Garden,” Smith coins the particularly withering insult: “That person is films on TV / five years back.”

At this point it may be tempting to call Smith’s vision “cinematic,” as more than a few professorial types in the past have staked a claim on his lyrics for literature, but this ignores the unbridgeable gaps between aural, written, and moving-image art—and he remained stubbornly a man of rock ’n’ roll. If a pure alchemic translation of The Fall’s music into cinema is impossible, however, a close approximation of the Smith persona can be found in a certain post-Thatcherite-apocalypse work by Mike Leigh, 14 years Smith’s senior and hailing from the same area of Salford. David Thewlis plays the distinctly Smithian Johnny in Naked (1993), a shambling, splenetic, caustic, absolutely Mancunian figure, putting the wrath of his bombast to all those that cross his path—a prophet in the London desert, roaming the Roman shell as feral and fierce in his discourse as was M.E.S. and his dreaded, undying yawp.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.