By John Anderson in the September-October 2000 Issue

Tender Mercies

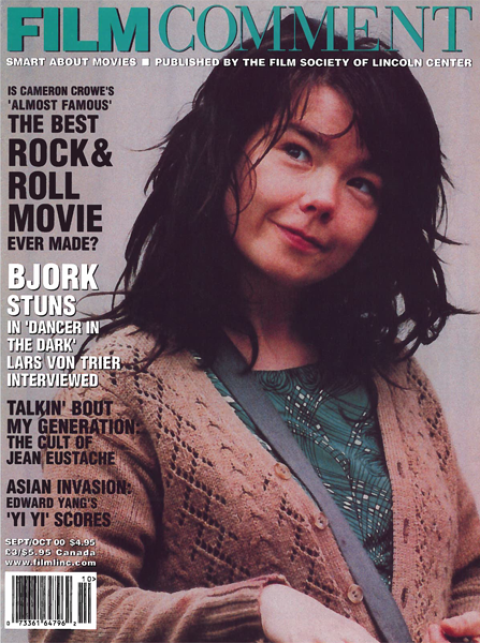

Edward Yang’s novelistic portraits of Taiwanese society capture the malaise of modern life with melancholy compassion

Did grown men weep at Cannes this year? Probably. God knows, there were reasons enough for anguish. But specifically: Did grown men weep at Edward Yang’s Yi Yi?

From the September-October 2000 Issue

Also in this issue

It’s been said they did. It’s easy enough to believe. Still, you have to wonder about such reports—and not just because mere crying would have been rendered inaudible by the clamor of the cell phone and the thump of the seat back. Specifically, you have to wonder why the weepers would have only been men.

Yang’s latest, his first since 1996’s Mahjong, does have a ruefully sentimental narrative, one almost guaranteed to agitate the tear ducts of men with regrets (not an exclusive club). And yet, in the intersecting, crosshatching arcs of its storyline, it offers emotionally wringing parallels for just about any audience—the same parallels that exist among its own characters, whose lives are reenactments, redemptions or just alternate takes of each other’s choices and foibles. (Yi Yi means, literally, One-One.)

More significantly, Yang, who along with Hou Hsiao-hsien is the best known of Taiwanese filmmakers and a social critic of gently ferocious mien, has achieved something with Yi Yi that has eluded him since his 1991 masterpiece, A Brighter Summer Day: a marriage of omnipotent observation and heartbreaking empathy with characters who may be foolish or flawed, but are never to be abandoned despite their most grievous sins.

These elements are presented in a film that is intricately yet seamlessly structured. The echo of each character’s story reverberates off the next with results that almost demand musical analogies (not to the sustained crescendo of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy, perhaps; more like the effect of the rousingly insistent, serpentine oboe of the Ninth’s second movement). The film’s lyrical fusion of disparate impulses creates a distinctly triumphal sound.

If one does weep, then, maybe it’s because of the realization—however subconscious—that the artistic impulse can—however infrequently—affect us so profoundly, even over the background noise of flapping seats, ringing phones, market fluctuations and real estate quotations.

For those interested in the films of Edward Yang, there’s an added feeling of vindication and empathy for a filmmaker whose earnestness has never been in doubt, but who has now managed to re-access his best instincts.

Though now he has bookended the decade with a pair of masterworks, Yang spent the Nineties making movies that were more respectable than revelatory. During this period, he attempted to create, both in theater and film, a kind of soul portrait of Taipei. A Confucian Confusion (94), for instance, is an aptly titled omnibus full of unhappy characters romantically involved with the wrong people for the wrong reasons—mostly money, which Yang sees as Taipei’s chief pollutant and major religion. A messy black comedy of ill manners and spiritual distress, the film was made before Asia’s mid-decade economic meltdown, when Taiwan’s wealth was as rampant as its paranoia. (Seen now, it’s as if Yang had a crystal ball tuned in to New York 2000.)

Yi Yi‘s bipolar characterizations were forecast in A Confucian Confusion—in which the story’s ultra-ethical novelist is married to the Oprah Winfrey/Tammy Faye Bakker-esque talk-show host; the magazine editor is engaged to the hotshot/hothead who’s financing her company; the accountant, trying to seduce the editor, tells her he can read in her balance sheets the innermost functions of her soul; the ultimate company man, engaged to the relatively guileless Qiqi, rationalizes a theory of national unity out of middlebrow taste. And the once-promising playwright—whose previous metier was “post-modern abstraction”—produces soft-headed television that panders to the masses because, after all, culture is a business and 20 million Taiwanese can’t be wrong.

That the oddball novelist is Yang’s self-deprecating stand-in in A Confucian Confusion seems pretty obvious to me; critic Jonathan Rosenbaum thinks the compromised playwright is Yang. Either way, the novelist’s daffiness shouldn’t be seen as a dilution of the director’s ongoing anger with the social politics of Taiwan. Even though the Cannes festival this year took place just as the island nation was experiencing its most traumatic political plate-shift since the Kuomingtang hit the rowboats, Yang expressed optimism that conditions, spiritual conditions, might change after a decade of having grown progressively worse.

“One of the unique things about doing films in Taiwan,” he said, “is that the political leadership—well, it’s very much like China. They don’t want to do very constructive things with cultural matters or anything that improves people’s intelligence. Honestly. They have certain rules you follow, and they encourage everyone to go into science, engineering, mathematics, anything practical . . . the humanities they discourage. They try to convince parents to instill social values that say these are the less important people in our society.”

The young Yang himself “gave in”—forsaking a career in architecture, which he had thought of as a discipline that could reconcile the creative and the technical. He opted instead for a degree in electrical engineering, which led to a move to the United States, where he received a master’s degree in computer design at the University of Florida. After that, he went west—enrolling, for just a year, in the film program at USC and then, after dropping out, spending seven years working for a computer company in Seattle. In 1981 he returned to Taiwan to pursue a filmmaking career—first as a screenwriter, then as a director. A vapor trail of Americana (Yankee caps, rock and roll, exported boorishness) has drifted through his work ever since.

During this period of germination, Yang recalled, the fledgling filmmakers who would eventually form Taiwan’s New Wave in the Eighties, including Hou, would hang out at his house, a house that lacked even a lock on the door. The scene suggests Burroughs, Ginsberg and Kerouac, hanging out and smoking reefer at Columbia; Hawthorne and Melville, hanging out and getting metaphysical in the Berkshires; Diz and Bird, rearranging jazz on 52nd Street—a serendipitous tryst of geniuses, each of whom would have had an impact on his art form one way or another, but whose mutual influences are evident and enormous. In 1985, the same year he made the essential A Time to Live and a Time to Die, Hou gave a startling performance as a disillusioned baseball player in Yang’s Taipei Story, a film that, as has been said, “helped to change the face of Taiwanese cinema.”

Taiwanese cinema before the New Wave was a corrupt business—as most business seems to be in Taiwan, judging by the picture painted in such films as Yang’s Mahjong. But the corruption itself was a catalyst for the New Wave, enabling Yang and his colleagues to make their first features.

“The party studio used to own everything,” Yang said. “And the guy at the head of it, he was cheated on so many projects—he spent millions of dollars making policy films. And he was so pissed at one filmmaker for spending $100,000 on coffee that he decided to give the young guys a break, with a very small budget, altogether $150,000—which is a lot of coffee.”

The film was the 1983 portmanteau In Our Time, a four-parter about growing up, to which Yang contributed “Expectations” (his only film, outside of A Brighter Summer Day, that can be construed as a period piece). It was scheduled for just a six-day run, but was so popular it eventually made another $150,000 on top of its budget. The rest, as they say, is Taiwanese history.

But it wasn’t easy. “At the beginning, no one would even work for us,” Yang said. “The attitude among the crews was, ‘We’ve been here for 20 years and these guys think they’re directors.’ My first day, I had drawn everything, storyboarded everything, but the cameraman was so terrible. Every shot, he was like, ‘An experienced director can do 35 shots a day. See how many you can do at the end of the day.’ I was on my 33rd shot when the guy said, ‘No. I’m not going to do this one.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ I was ready to beat him up.”

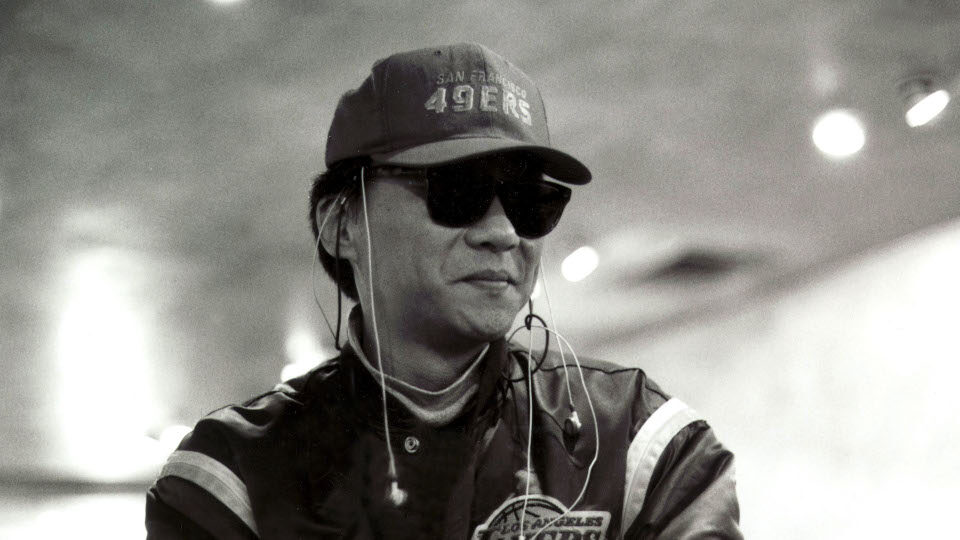

Edward Yang - 1994

Yang had arrived at the right time. The Taiwanese population was hungry for films about itself and disposed to films of gravity—and apparently, length: on the subject of Yi Yi‘s international distribution, Yang said he was willing to cut the three-hour film in order to get it seen outside Taiwan, just as he had cut the original A Brighter Summer Day from its nearly four-hour length to 202 minutes. “But I’m an engineer,” he added. “Eventually, the integrity of the structure is at stake. You can cut flesh off a film, but at some point you’re talking about amputation.” Yi Yi, one of the few of many three-hour-plus films shown at Cannes this year that actually justified its running time, would have no problem finding an audience at its current length in either Taiwan or Japan (the source of the film’s financing). Hong Kong and the States, however, were another story.

Duration is just one aspect that bonds A Brighter Summer Day to Yi Yi, which now have to be considered the twin pillars of the Yang oeuvre. They are linked as well by their autobiographical elements, and also the way in which they reveal how Yang’s eye has metamorphosed over a ten-year period.

The dispassionate/passionate perspective that characterizes his movies can be seen even in Yang’s first feature as writer-director, the landmark That Day on the Beach (83) and certainly in The Terrorizer (86), in which gunshots ring out during a gambling bust and the tension mounts because—as we travel through the neighborhood—we know that not everyone has heard the gunfire, or knows enough to get out of the way.

It’s also easy enough to see a commonality in the way Yang and Hou move their cameras—or, rather, don’t; the static shot is as important as any onscreen action in either’s films. It’s also apparent enough that by the time of A Brighter Summer Day, the POV has become a character.

It’s neither blight, nor summer; the film’s title comes from a misheard lyric in a song by Elvis Presley, just one of the western fascinations of the young, doomed Si’r and his fellow Little Park gang: Cat, Sly, Blind Man, Deuce, Red Bean, Airplane. Their gangster posturing, the brutal violence of their initiation rites and their seemingly reluctant nihilism is offset by their distinctly schoolboy manner. The escalating level of their criminal acts—and, specifically, Si’r’s general anger, and screwy romance with Ming—may belie the fact, but they are kids, not to mention the mixed-up byproducts of a culture that has deprived them of a sense of place.

The families of most of these lost boys fled to the island in 1949 (Yang himself, born in Shanghai in 1947, was the child of a government worker who brought his large family there when Yang was a small child). Preoccupied by dreams of retaking the mainland, these nouveau Taiwanese treat their new land like a way station, not unlike the Cubans in Miami. The result is a younger generation who grow up hearing the only home they know being consistently denigrated by the people responsible for them being there. That they turn a deaf ear to their elders while being drawn to the borrowed culture of the west—and the samurai swords left behind by the departed Japanese—isn’t hard to understand.

Yang never uses anything that would qualify as a close-up—given the intimacy he does achieve, a western-style close-up popping into one of his movies would seem the height of vulgarity. The most tender moments of A Brighter Summer Day are the two-shots of Si’r and his father: in one, Dad has defended Si’r before a school disciplinarian, who has accused the boy of cheating. How can the boy admit to something he didn’t do? the man asks, deriding the school administrators as “bureaucrats.”

Later, after Dad has been grilled, humiliated and forced to sell out a friend during a government interrogation, he nearly grovels before the same school administrators. And it becomes clearer than ever that Dad’s worldview, formed in Shanghai, is as incongruous to Taiwan as the Elvis Presley impersonators who entertain at the local dance.

Elvis—whose songs are sung so angelically and phonetically by the two young singers in the film—is a distinct presence in this world, where native rootlessness leads to a fascination with hijacked, mutated culture. The boys watch Rio Bravo at a local theater. The Godardian gangster pose of Honey—the fugitive killer whose troubled girlfriend Ming is shared with Si’r—is a caricature of the Hollywood outsider, although his fate is real enough. Based on the real-life Taipei murder of a 14-year-old girl by a male high school student in 1961, A Brighter Summer Day takes to its logical conclusion the mutual contempt of people thrown together by circumstance, just as he does in the later Mahjong, although with much more violence.

Around any and all indignities, Yang creates a frame that means to impose control over the often feverish misbehavior of its subjects. And when the camera drifts away—or when it remains motionless and allows its subjects to drift off—it’s delivering a judgment, not just on the action but on the director. It’s as if he’s saying, I can do nothing about what is happening here; I don’t approve of it, so I will turn my eyes away. There’s a conspiracy of intelligence formed by this kind of filmmaking; it presumes a sophistication on the pmt of the audience that is, or should be, repaid by the viewer’s emotional investment.

Such is the case with Yi Yi. Set in present-day Taipei (as are almost all of Yang’s films, immediacy being among their strongest traits), the film is chiefly about NJ (Wu Nianzhen), a rather melancholy father and businessman whose failing computer company is looking for an angel. As the most “honest looking” of the company’s principals (an irony; he really is the most honest), NJ is assigned to discuss a merger with a games designer named Ota (Issey Ogata). Although Yang denies it was intentional, Ota’s Moe Howard haircut and crewneck sweaters make him look like a Japanese version of Bill Gates—although in both his good nature and integrity, Ota turns out to be NJ’s soulmate. And as NJ’s family suffers multiple crises his mother-in-law’s stroke, his wife’s nervous breakdown, his brother-in-law’s bankruptcy, his own encounter with a long-lost girlfriend—he finds solace in the idea of teaming up with Ota, who offers a kind of redemption from the cynicism that surrounds NJ in his professional life.

Following their own analogous paths, meanwhile, are NJ’s teenage daughter Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee) and eight-year-old son Yang-Yang (Jonathan Chang). Ting-Ting, in her desire for romance, seems to be reliving her father’s own disastrous first affair; Yang-yang, whose problem seems to be that he’s a born artist (hence the name, we assume) is having more than a little trouble at school and refuses to talk to his comatose grandmother.

A Brighter Summer Day is like a first novel; Yi Yi is a work of maturity in which the pent-up frustrations of youth have given way to an acceptance of human frailty and life’s various possibilities. Likewise, Yang’s eye is less judgmental now; when the camera fixes on what it sees, and characters move beyond the frame, the effect is an expansion of the world, and possibly the heart, rather than a departure from both. There are still things it doesn’t want to see, but it doesn’t look away. It gathers, and embraces.

Wu is a veteran Taiwanese screenwriter (as well as writer-director of a 1994 film with a very Yang-ish theme, A Borrowed Life), but he has only ever acted in Yang’s films. Yang has often been forced by the realities of Taiwanese culture, and perhaps prefers, to work with non-actors. Two, the young Lee and Kelly, deliver wonderful performances in critical roles.

When Yang was young, he showed talent as a cartoonist and won prizes for his manga art. The animated sequence in Yi Yi is one of the few references to that among Yang’s films, although both A Brighter Summer Day and Yi Yi contain a single moment of near hallucinatory beauty that departs completely from their otherwise matterof-fact style—glimpses of the divine, you might say. In A Brighter Summer Day, the moment occurs when Jade, dressed in yellow, having spurned Si’r’s advances, crosses a tennis court at night, hands outstretched—a shot that dissolves into daytime and a passing train, the striated elements of one image seeming to explode into the next.

In Yi Yi, young Yang-Yang sits in a darkened room as an educational film plays and an older girl his tormenter/love object—walks in and across the path of the film’s projection. The passing clouds and elevated light projected onscreen turn her glorious; Yang-yang, transfixed, has his Proustian madeleine moment in a collision of flesh and film.

You want to cry? Here’s your moment. Yang made notes for what would eventually become Yi Yi 15 years ago, when a friend’s father went into a coma. “I knew I was too young at the time,” he told Reuters during this year’s Cannes festival, “so I put it aside.” Timing is everything. Nearly. Judging by Yi Yi, knowing when not to act is just as essential to art as it is to Yang’s characters, who more often than not are stampeding blithely toward their own personal abyss.