By Film Comment in the May-June 2019 Issue

Personal Effects

A selection of buried treasures from 50 years of Film at Lincoln Center

From the May-June 2019 Issue

Also in this issue

To celebrate the Film Society’s 50th anniversary, we asked contributors from different parts of our industry to write about a film that played at one of the institution’s festivals or series over the years that reflects its daring and forward-thinking approach to cinema.

CHOUGA DAREZHAN OMIRBAEV, 2008 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

Darezhan Omirbaev’s films were recommended to me by Philippe Garrel, and they were every bit as good as he told me they were: visually and emotionally precise, bracingly and often pitilessly sharp, unexpectedly funny, open to exaltation, and always surprising. They were also poetic in the very best sense of the word—as in all good poetry, every element of Darezhan’s films is exactingly calibrated. In contrast to the majority of filmmakers from the former Soviet republics, he is a determined miniaturist (the better to be left alone, I suppose). And where most Russian and Central Asian filmmakers of his era worked under the long shadows of Andrei Tarkovsky and Aleksei German, Darezhan turned to Bresson for inspiration. Chouga, his fifth feature, is based on Anna Karenina. The alleged incongruity of a tightly compacted 91-minute modern-day adaptation of an 800-page classic of world literature seemed to throw a few critics when we invited the film to the 2008 NYFF, which took place in the old Ziegfeld. As a matter of fact, I took great pleasure in introducing Chouga by commending the packed audience for not believing everything they read in The New York Times, where it was not just panned but condemned. The reaction was a warm one. Darezhan has completed only one feature since Chouga. I hope he is able to get another film made soon.—Kent Jones, NYFF Director

COSMOS ANDRZEJ ZULAWSKI, 2016 FILM COMMENT SELECTS

Andrzej Zulawski passed away two days before he was scheduled to appear at the Film Society accompanying the U.S. premiere of Cosmos, part of a sidebar tribute to the Polish director. A faithful modernization of Witold Gombrowicz’s final novel, Zulawski’s last film is told with one of the strangest light touches of his career. The plot involves an unpredictable series of macabre and burlesque events—beginning with a young writer’s chance encounter with a hanged sparrow—that unmask a dark world controlling every aspect of the human experience and our absurd urge to make sense of it. Much has already been written about Zulawski’s breakneck histrionics; more can always be said about his sense of humor. A meta-physical comedy-mystery that obsesses over a Donald Duck impression, conjures an adult Tintin lookalike, and concludes with a corrective hair flip, Cosmos is a single, coherent work constructed of mixed metaphors and non sequiturs—it’s a shame that too few directors could (or would even be willing to) sustain such a feat. The influence of Gombrowicz in much of Zulawski’s cinema is as fruitful as it is plain, but it’s Cosmos that most deliriously combines the two artists’ profoundest and funniest ideas about creativity in our present day.—Tyler Wilson, Assistant Programmer, Film at Lincoln Center

DAUGHTER FROM DANANG GAIL DOLGIN & VICENTE FRANCO, 2002 NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

Gail Dolgin and Vicente Franco’s Oscar-nominated Daughter from Danang travels a straightforward path before taking an abrupt plunge off a cliff into an abyss of emotions too painful to even name. The film follows Heidi Bub (née Mai Thi Hiep), who was airlifted out of Vietnam in 1975 with thousands of other children via the U.S.-sponsored Operation Babylift, as she goes back to Vietnam to meet her birth mother for the first time. After a tearful embrace in the airport, the reunion derails with such swift totality that it’s impossible to catch your breath (Dolgin and Franco keep the film at a tightly wound 80 minutes). Raised by an authoritarian single mother in Tennessee who told her to hide her origins, Bub is so unprepared for the culture clash and so blindsided by her birth family’s expectation of financial support, that by the end of her short visit, she is quite literally desperate to go back to America. Whatever Dolgin and Franco may have expected for their project initially, the end result is provocative and challenging. Like other documentaries such as Gimme Shelter, Capturing the Friedmans, or Operation Filmmaker, Daughter from Danang had to change course mid-filming to incorporate the unexpected turns of a real-life event. What the film leaves us with is a vast sea of incomprehension and pain, with no shared language to bridge the gap. It’s devastating.—Sheila O’Malley, critic

Photo: Rolf Konow

DOGVILLE LARS VON TRIER, 2003 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

Lars von Trier has always been denying himself one thing in order to indulge more shamelessly in another. After years of clinical exercises in high style (culminating in the dizzying, if sterile, bravura of Europa) and the Dogme 95 manifesto, which he only wholly submitted to once with The Idiots, he allowed his mischievous side further reign with Dogville. Reportedly inspired by the “Pirate Jenny” ballad from Brecht-Weill’s The Threepenny Opera, the film establishes a smirking portrait of American charity, staging a gleefully misanthropic revenge allegory on a bare soundstage, with only chalked outlines on the floor to suggest the architecture of this metaphorically and literally transparent town of cowards, scoundrels, and hypocrites. When our Christ-like heroine, Grace (Nicole Kidman), is climactically asked what she wants to do with the people of Dogville, who have by then shown their true barbaric colors, our Hollywood training tells us to expect clemency. When she then responds by cold-bloodedly sentencing Patricia Clarkson and her brood of heartless brats (the most monstrous of whom hilariously resembles the director) to death, it becomes thrillingly clear that we’ve just submitted ourselves to a brilliantly argued, three-hour justification for the eventual massacre of a hopelessly corrupt town (just like yours). Has any end-credits song sent you out of the theater with more invigorating smugness than Bowie’s “Young Americans,” as applied here? Brecht would have been dancing in the theater.—Ari Aster, filmmaker

DOOMED LOVE MANOEL DE OLIVEIRA, 1980 NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

In 1980, New Directors/New Films featured fresh, 71-year-old Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira, a giant of European art cinema who had recently embarked upon a remarkable second phase in his career. Arriving stateside two years after its debut on Portuguese public television, Doomed Love is Oliveira’s ambitiously mounted adaptation of Camilo Castelo Branco’s epic novel of the same name. Running nearly five hours, the film tells the story of Teresa (Cristina Hauser) and Simão (António Sequeira Lopes), 18th-century lovers whose relationship is thwarted by a feud between their aristocratic families. With the grandeur and elegance that would come to define his cinema, Oliveira stages Branco’s tale of tragic romance and societal repression through a radical conflation of history and modernism. His emphasis on the linguistic nuance of Branco’s text (delivered in either voiceover or highly mannered readings by the actors), coupled with an ornate mise en scène based on the unique integration of sequence shots and tableaux vivants, enabled Oliveira to artfully consolidate narrative traditions related to theater, literature, and cinema. For Oliveira, such distanciation devices weren’t a rebuke to the medium’s established language so much as a case for its aesthetic virtues and continued relevance, a notion he would spend the next three and a half decades reinforcing, until the age of 106.—Jordan Cronk, critic/programmer

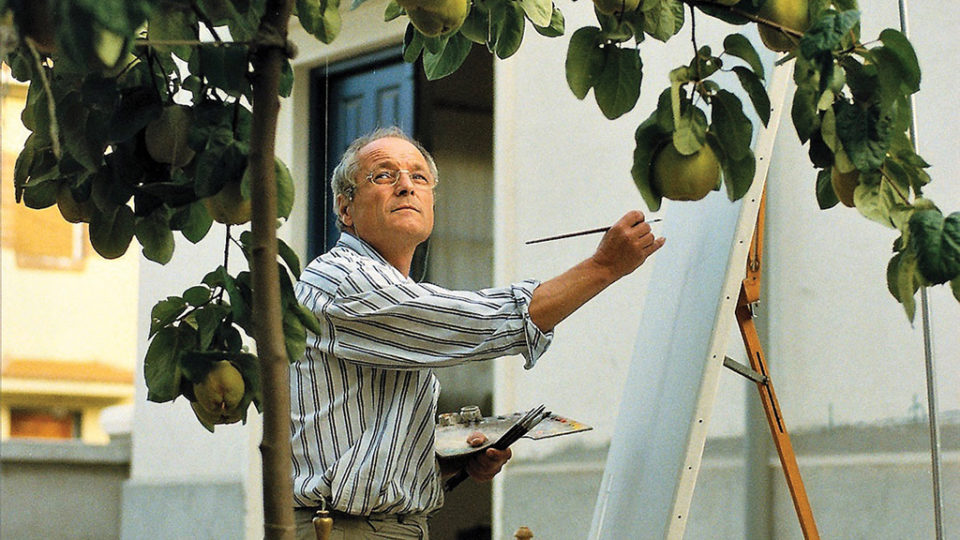

DREAM OF LIGHT / THE QUINCE TREE SUN VÍCTOR ERICE, 1992 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

You may watch movies for aesthetic awakening. You may watch movies to learn a little something about processes outside your personal experience. You may watch them for emotional comfort or, conversely, to challenge your perceptions about art and the world. Movies may help you breathe a little easier, see the world a little clearer, and maybe, just maybe, help you drift away into reverie. Encompassing all of these, Víctor Erice’s Dream of Light is one of the fullest movies I’ve ever seen, at once limning the contours of what cinema is and expanding what it can be. With this buildup, one might expect some sort of grand, all-consuming spectacle, but this odyssey of the mind is—quite simply, and not simply at all—the documentation of a single man trying to complete a painting of a fruit tree in his backyard. The light has to be perfect; the weather has to be right. He has to construct an always-precarious rig that keeps the quince in its right place. Months go by. He has to deal with his own doubts, his dreams, and his own mortality. That the man is Spanish painter-sculptor Antonio López García “playing” himself makes this peerlessly existential film technically a work of nonfiction, but Erice, whose The Spirit of the Beehive remains a kind of blueprint for a cinema of interiority, makes it also something else: cinema’s greatest, purest action movie.—Michael Koresky, Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy, Film at Lincoln Center

EK DIN PRATIDIN / ONE DAY LIKE ANOTHER MRINAL SEN, 1980 NEW YORK FILM FESTIVAL

Mrinal Sen, the most radical of India’s parallel cinema pioneers, once said that his goal as a filmmaker was to “make things look unpretty, to keep the rough edges.” At first glance, his Ek Din Pratidin seems to belie that motto. Set over the course of a single night, the film captures the anguish of a lower-middle-class family when their sole breadwinner, a young woman named Chinu, doesn’t return home from work. From the chiaroscuro opening shot of a narrow Calcutta alleyway to the camera’s sinuous movements through the family’s crumbling tenant house, Sen directs the film with elegant, atmospheric precision, bereft of the formal and tonal affectations of his other features. And yet, his rough-edged social critique bristles under every frame. The fears of urban life are illustrated harrowingly when Chinu’s brother visits the morgue, checking corpse after corpse for his sister; meanwhile, judgmental whispers trickle through the thin walls of the tenant house, compounding the family’s anxious speculations about Chinu. Sen’s quiet chamber drama becomes an absurdist play of gendered ironies, where the only acceptable explanation for a woman’s truancy is death. Chinu finally returns late at night, but we never learn why she was gone. Sen indicts us with our own curiosity.—Devika Girish, critic

JOYCE AT 34 JOYCE CHOPRA, 1973 MOVIES IN THE PARKS OUTDOOR SERIES

So many movies culminate with a dramatic scene in the delivery room, with everything resolved by the time the baby arrives. Not so in Joyce Chopra’s Joyce at 34, a personal documentary, co-scripted with Claudia Weill, chronicling the birth and early months of Chopra’s first child. The movie begins with Chopra describing her pregnancy as a sort of limbo, inconvenient biology that she likens to an interminably delayed film project. Within the first 90 seconds, Chopra is in labor and then gazing at her daughter. The bond is clear in an instant, but everything is not resolved, because the child will not be Chopra’s entire life. Chopra and Weill show groups of women of their mothers’ generation as well as their own, talking about the impossibility of balancing work and motherhood. The older women often looked for work to keep them close to their children; some of the younger women question having children at all. The conversation seems timeless, but Joyce at 34 remains hopefully in its present moment: Chopra holding her baby while sitting at a Steenbeck editing console, trying to make it work.—Nellie Killian, independent programmer and FC contributing editor

NOIR ET BLANC CLAIRE DEVERS, 1986 NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

Claire Devers’s steely, intrepid Noir et blanc shares several fascinations with early work by her countrywoman and near-namesake, Claire Denis. Some are thematic: pressurized masculinity, interracial tensions and fetishisms, and social relations tilting into violence. Formally, both women’s films linger on exposed skin and machinic musculature, slide easily into abstract montage, and exacerbate visual tensions with potent sounds from off-screen sources. One cannot watch Noir et blanc without wishing Devers had reaped as many opportunities as Denis to articulate and evolve her own aesthetic. Adapting an incendiary story by Tennessee Williams, Devers barely needs dialogue to chronicle the sadomasochistic bond between a scrawny white accountant and the black masseur he hires to assuage his muscles and, later, to break his bones. Declining a Mapplethorpe-style exoticizing of the masseur’s body and omitting the gruesome apotheosis of Williams’s tale, Devers generates shocks through more singular means. Humid legacies of racism, empire, and queer outlawry seep from Noir et blanc’s images, without offering a legend to decode the movie’s meanings; they permeate a dank, dangerous liaison driven by the characters’ strange, specific desires. The personal gym, that exemplary 1980s temple of spit-polished self-improvement, becomes a venue for seedy allegories, private as well as public, and all the more disturbing for remaining defiantly inscrutable.—Nick Davis, professor and FC contributing editor

RETURN OF THE SECAUCUS 7 JOHN SAYLES, 1980 NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

In April 1980, a decade before my birth, John Sayles’s debut feature Return of the Secaucus 7 premiered at ND/NF, alongside Manoel de Oliveira’s Doomed Love and Shohei Imamura’s Vengeance Is Mine. An emotionally intricate, small-budget chamber piece, it depicts seven youngish adults who reconnect years after being arrested together en route to an anti-war march, stirring up old dramas and new angst as the preoccupations of adulthood collide with nostalgia for the passions of youth. With this premise, the 29-year-old Sayles announced himself as an artist to watch, thoughtful and funny and keenly attuned to his generation’s ambient cultural frequency, well-equipped to capture the quicksilver energy of an electrifying moment of transition in the history of American politics and American filmmaking. When I first saw the film as a teenager, I was quick to mine it for insight into the minds and hearts of my parents and their peers, and the world in which they had come of age. When I revisit the film now, as a youngish adult in my own right, it feels as new and essential as I imagine it must have felt to youngish adult New Yorkers like me, four decades ago.—Madeline Whittle, Programming Assistant, Film at Lincoln Center

SANRIZUKA: PEASANTS OF THE SECOND FORTRESS SHINSUKE OGAWA, 1973 NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

In the late 1960s, Tokyo’s authorities chose the city of Sanrizuka as the site for the new Narita International Airport, setting off a violent struggle with the local farmers and peasants, who chose to resist the seizure of their land. From 1968-77, filmmaker Shinsuke Ogawa and his collaborators in the documentary collective Ogawa Productions made a cycle of six films depicting this conflict. The pinnacle of the series, and one of the most vital, committed, and convulsive of all docs, Sanrizuka: Peasants of the Second Fortress, chronicles the extraordinary methods the farmers devised in order to defend their homes. Far from a toothless protest of placards and slogans, their resistance is a full-fledged armed battle, one which—given the farmers’ poverty and lack of modern weaponry—takes on an incongruously medieval cast. By 1971, the inhabitants of Sanrizuka had constructed elaborate fortresses, dug a network of tunnels, and transformed themselves into a formidable guerrilla army. For his part, Ogawa had by now adopted a practice that jettisoned the pretense of documentary objectivity, instead wholeheartedly embracing (and embedding himself within) the struggle. Nevertheless, the film’s masterful intermixing of intimate testimony with visceral battle sequences is every bit as astonishing as its political immediacy and commitment. Ogawa would go on to relocate his collective to the rural village of Magino, where he would produce such masterpieces as Raising Silkworms (1977) and Magino Village: A Tale (1987). His body of work is still woefully under-recognized in the U.S., despite having inspired a film by none other than recently deceased experimental filmmaker Barbara Hammer: Devotion: A Film About Ogawa Productions (2000).—Jed Rapfogel, Programmer, Anthology Film Archives

STRANDED IN CANTON WILLIAM J. EGGLESTON, 2006 FILM COMMENT SELECTS

Over the past two decades, Film Comment Selects has shown extraordinary work by filmmakers tapped early in their careers for their demonstrated promise, as well as directors whose brands were, temporarily or temperamentally, not widely adored. That has left behind a daunting list of alums, including Olivier Assayas, Yorgos Lanthimos, James Benning, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Chantal Akerman, and Christian Petzold, though perhaps the most spectacular example was our 2008 Closing Night selection, Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker, which of course the Academy and the rest of the world would eventually catch up to. But one of my personal favorites is Stranded in Canton, sui generis as only something filmed by master photographer William Eggleston could be. A mesmerizing Portapak mystery tour through Memphis in 1974, it seems more like a rambling ghost party than anything else (it also appeared in excerpts in Michael Almereyda’s William Eggleston in the Real World, then a recent release). It’s a 76-minute, unfiltered, woozily careening tour of so-real-it’s-unreal folks with Eggleston’s own occasional voiceover, and his bobbing camera pushing forward to say hello, in a cinematic portal to the wholesale weirdness of another moment.—Nicolas Rapold, Film Comment Editor-in-Chief

WHAT WE DO IN THE SHADOWS/ANGST TAIKA WAITITI & JEMAINE CLEMENT/GERALD KARGL, 2014 SCARY MOVIES

Horror-comedy is tough to perfect, but writer/director/stars Taika Waititi and Jemaine Clement nailed it with What We Do in the Shadows. Though anemically distributed theatrically, this bloody yet hilarious, twisted yet heartfelt film—currently being further memorialized as an FX cable series—will be remembered as a hugely quotable, all-time great. The ultimate Scary Movies opening night offering, it was matched by an epic Q&A in which a straitlaced Clement appeared in character not as a vampire but a serious doc filmmaker, and all the questions, including the audience’s, went along with the ruse. Our closing-night selection that year was also a revelation: Angst (1983), a movie I first saw on an old VHS copy owned by Gaspar Noé, is the only narrative feature by the Austrian Gerald Kargl, showcasing a staggering performance by Erwin Leder as a murderer fresh from prison who falls right back into the killing game, targeting a family of three before his release day even comes to a close. Brilliantly shot and scored and oozing with dread, it’s a cinematic experience that begs for the big screen; after six years of ever-so-polite refusals along with encouragements to keep asking, Kargl agreed to loan out his personal, uncut 35mm print to us. What We Do in the Shadows jokingly plays itself as truth and Angst is genuinely inspired by reality, but they’re ultimately not such different beasts: both films’ monsters suck the life from their victims to strengthen themselves—just as the films’ singular energies serve to feed and enrich their audiences.—Laura Kern, Scary Movies Programmer and Film Comment Managing Editor

A WOMAN ALONE AGNIESZKA HOLLAND, 1987 NEW DIRECTORS/NEW FILMS

In 1987, six years after Agnieszka Holland’s A Woman Alone had shown on the Western European and Canadian festival circuits, ND/NF gave New York audiences an opportunity to see the first of several masterpieces in what is now Holland’s prolific 40-plus-year career. The NYFF had already shown the director’s Angry Harvest (1985), set in Poland during World War II and one of the most incisive and unsparing dissections of anti-Semitism ever made. But, like almost all of Holland’s films, it offers a sliver of hope at the end. A Woman Alone, however, is devastatingly grim from the first shot to the last, although punctuated by Holland’s signature mordant humor. The titular character is a single mother, whose job is delivering sacks of mail that weigh nearly as much as she does. Belonging neither to the Communist party nor to the Solidarity movement, she has no support system. Her son hates her, and everyone she knows is a thief, miser, or both. Increasingly desperate, she hooks up with a disabled man who is even less rational than she has become, and they cook up a plan to escape to the West, which ends badly—as badly as the brief period of liberalization in Poland, during which Holland could make a film that attacked the utter failure and corruption of Soviet-imposed communism, which would result in martial law and Holland’s eight-year exile.—Amy Taubin, FC contributing editor