By Lawrence O'Toole in the September-October 1980 Issue

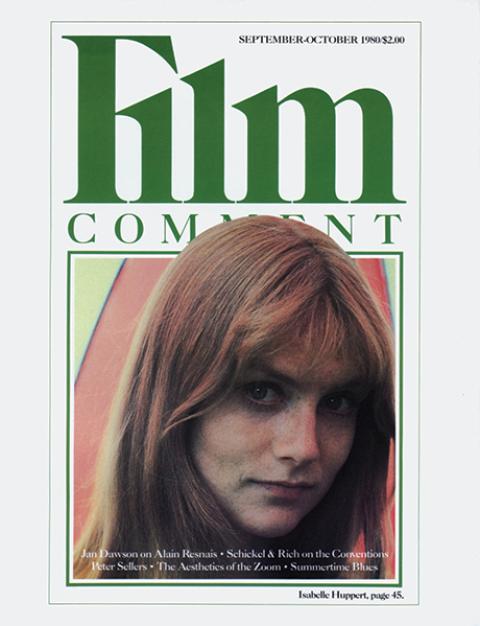

Isabelle Huppert

The iconic actress on her extraordinary early-’80s run of films

From the September-October 1980 Issue

Also in this issue

To celebrate the upcoming 50th Anniversary of the Film Society of Lincoln Center, Film Comment will be making some classic pieces from our archive available online. This week, read Lawrence O’Toole’s 1980 conversation with the iconic actress, who starred in Loulou, The Heiresses, and Sauve qui peut (la vie) that year alone.

It’s possible she has more freckles than Sissy Spacek. And, like Spacek, she’s diminutive; except it’s probably better to say she’s petite, for she is French. Isabelle Huppert (her last name is pronounced as though it were some exotic concoction the French conceived with a fruit) is, make no mistake about it, French: her copy of Cahiers stares boldly (seems to, anyway) from the coffee table of her hotel room. She is 25. Since 1971 she has made 25 films. The daughter of a suburban middle-class French family of Hungarian descent, a very good girl who embarked upon Russian studies before the screen nabbed her, she sits in her hotel room, afflicted with a summer cold, having just completed The Lady of the Camellias under Mauro Bolognini in Rome. The world is full of the tiniest coincidences, benign as they may be.

Huppert is wearing a Heaven’s Gate T-shirt and jeans, her legs curled under her as though it were the proper (and only) way to conduct a conversation. She has returned to America to add the last vocal touches to Michael Cimino’s $30-40 million (depends upon who you talk to) Western epic, her first film in America. She’s excited: about her role in Heaven’s Gate and about going to see Barnum that night. A cold? Who cares? Smoke if you wish… I’m deathly tired… but let’s go out on the town.

This year Huppert was everywhere in evidence in that colic cathouse called Cannes. Three movies: Maurice Pialat’s Loulou; Marta Meszaros’s The Heiresses; and (coup de grace) Jean-Luc Godard’s return, Sauve qui peut (la vie). Three large, looming performances, each with a dramatic degree of difference to them. No prize. Tiens, you know Cannes. Besides, she got her prize in ’78 for Violette, the young murderess with a fondness for furs and cloche hats (and pictures of Bette Davis and Lillian Gish perched, poignantly, on her dresser). The casual moviegoer knows her as The Lacemaker, a parlor assistant who, meeting her first love, becomes sickly: a portrait of the woman as a “sweet young thing.” Not since Joan Fontaine in Letter from an Unknown Woman: silly, stupid, but really gets to you.

Among the roles she has essayed include Anne Brontë in Andre Techine’s The Brontë Sisters (not her fault), Romy Schneider’s kid sister in César and Rosalie, the teenager who gets slapped around in Bertrand Blier’s Going Places, the Greek (yes, Greek) teenager searching for her friend in Preminger’s Rosebud, a film that deserved the fate of the sled of the same name.

The three roles in Cannes augur. As Isabelle, in the Godard, she is the emotionally lassitudinous hooker who has little time for anybody or anything other than the thing she’s doing, other than an inner recognition of her lot. Huppert can easily harness that kind of thing. In Loulou she plays Nelly, a middle-class girl who falls for an overgrown delinquent, but who stands by her man. Her finest performance so far, at least from this angle, is in The Heiresses: the quiet shopgirl, Irene, a Jew, who is contracted by a rich woman to have a baby for her. The triangular relationship entered upon with the rich woman and her husband is reticular, finally leading her quietly to her doom. In The Heiresses, Huppert keeps tensions trekking across her face.

The art of Isabelle Huppert is the art that would rather reveal than show. It coaxes the camera, does a mating dance with it: I will show you things but you must be watchful for them. It seems to be an art that never attempts to deceive. There’s a splendid opacity there.

Someday, says Huppert, she would like very much to do Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

The Lacemaker (1977)

You are a very quiet actress. That is, rather than throw yourself toward the camera, you draw the camera toward you. Is that description fair?

Yeah.

For most actresses it’s the reverse.

I guess I don’t like the reverse. I don’t like it as a spectator. Also, I think I’ve changed a little, I have a tendency to project a little bit more lately. I don’t know—I guess it’s my way of being in life, you know.

You have said elsewhere that acting for you is a kind of therapy, a way to rid yourself of certain anxieties. When one thinks of acting as a form of therapy, one tends to think of emotions being displayed in a theatrical way. Yet your performances in Violette and The Heiresses aren’t theatrical in that sense.

Yes, but being in front of a camera is always a type of projection. The fact of being an actress is a projection itself.

The camera, it’s said, either loves or hates people…

That’s true.

Did it take you a while to get used to the camera, or did you feel an affinity for it almost immediately?

Yes, since the beginning.

When you were growing up did you have any heroines—movie heroines—actresses you were drawn to? Or a particular style of acting that excited you?

No. I have no masters.

Did you see a lot of films?

No, less than the average person. I lived in a suburb and there weren’t many movies, so I didn’t go often. I have big holes in my knowledge of movies.

Can you remember the first time you knew you wanted to act? Was there a specific moment when you knew?

No, never.

Did you fall into it? How did it happen?

I guess something was pushing me toward this. But it was not conscious.

Have you figured out now what that something was?

It’s the same for everybody. All you can say about it is really clichéd and the rest you can’t tell because it’s very… I guess it’s so mysterious. But the main reasons are always the same: to be loved, to be seen, to be admired, whatever.

Do you still have the sense that there’s another, more deeply buried anxiety that you need to rid yourself of through acting?

Yes, there’ll always be another anxiety. I don’t think acting solves any problems; it merely puts you in situations where you can—how can I say?—feel confined. You don’t see much people. Strangely, you don’t have to go through the kind of socialization you would otherwise, meeting people when you don’t want to. I would normally have to socialize, but the exercise of this position does not require much socialization. In this sense being an actress is a help, when you don’t like to socialize or communicate too much. This could be an anxiety. It’s true that most of the time actors and actresses are withdrawn people. I think it’s true for any of the arts.

Do you consider yourself a loner by temperament?

Yeah.

How do you feel when you are required to go through a whole list of people who are interviewing you?

I hate it, but I’d like to explain why I hate it, because maybe I don’t hate it that much. I read an interview with Robert Aldrich—he wrote a book—and he wrote this little anecdote about John Ford. He [Ford] said he used to hate journalists. So when a journalist would come to the set he would send him away. Then he would desperately try and find his address to call him back and say he would like to be interviewed. John Ford would talk a lot and then ask the journalist to burn everything he’d told him. I like this little story very much, for it strikes the mood. Sometimes you want to talk, not want to talk, tell everything, not tell everything. I feel very much the same way.

So it’s really a matter of mood. Catch someone on a good day.

Well, yes, maybe. Maybe.

There’s another side as well: the journalists who are sent out to interview and can’t come back empty-handed.

Everyone has their cross to bear.

The way I look at it is you might as well enjoy carrying the cross.

Once you have explained what I have explained, you can. First you have to be angry and then you can be pleasant.

You’ve said you have a great respect for the directors you work with, as well as a great faith in them. Godard, for instance. Did you work well together on Sauve qui peut?

It was okay. Actually, speaking of Godard, I have to speak of all the directors I’ve worked with. As long as they are talented and good, I totally enjoy their authority over me—moral and artistic authority. Ordinarily I go under their law.

Do you have a fear that if you place all your trust in a director you’ll be led the wrong way? Especially if it’s a director whose work you aren’t familiar with.

It’s true that it was easier for me with Godard. If you like Godard, it’s not very difficult to trust him. Yes, sometimes it relies on the fact that a director has done a lot of things and I know his work. If he has not done a lot of things, then the trust is based on his personality.

Do you prefer to be directed gently rather than have a director hammering away at you for endless retakes of a scene?

I don’t mind. Cimino was hammering, but in a very gentle way. Godard only does a few takes for each scene. I really don’t mind; each director has his own way. Otherwise it would be boring.

When I saw The Heiresses in Cannes this year, it occurred to me that it was one of the few movies directed by a woman where I had the sense that a man couldn’t have told me the same things.

Yeah, that’s true.

Was there a difference being handled by a woman director?

Yes, the noticeable difference was that you are less handled by a woman than a man. It has to do with her history. For centuries she hasn’t the habit of handling certain things. It’s also a matter of her relationship to power; it’s not the same as a man’s. We don’t expect a woman to be that powerful.

Let me read you a quote you made regarding The Lacemaker: “I had a hauling over the coals by some American women who saw The Lacemaker as a typical masculine vision of a woman. They were right.”

Excuse me, I have to read it. [Pause] “Hauling”: what does it mean?

Criticism.

Ah. Looking back at the movie, it’s true that it’s a masculine vision. But it’s not because it’s a masculine vision that the movie should not have been made. A masculine vision exists—why not show it? I was not aware of it while I was doing it: I was too much into the character. I still like the movie, I still think it’s a good movie. It’s… it’s finished. I had a very narcissistic relationship to the part at the time. Also, it’s an image of myself that I don’t have to have anymore—that any woman should have to have. But I don’t agree when women say it’s a bad movie and that it shouldn’t have been made. It was just in its observation, totally just and fair—it was not a lie. It was a man’s vision for sure. In its sensibility it was perfectly just. There was nothing wrong, except that it’s not a very cheerful destiny for a woman.

Is there a difference between what you do on screen and what you perceive yourself doing when you watch yourself on screen?

I don’t like to see myself up on the screen. I’ve been working hard for two years making many movies and it makes me feel depressed to watch. When you make a film you feel you’ve made it with your own flesh and blood. Then you see the film, and you look at this and you say “Oh, all this for only that”—or, I mean, “All of that for only this?”

Do you have any regrets about what you’ve done? Are there performances you’ve felt weren’t quite what you wanted?

No, I never have any regrets. I have regrets of the present, never of the past. You can try to make the present better, but the past—forget it.

You’ve played a lot of victims: Violette, The Lacemaker, The Heiresses. Do you think you have a special quality that equips you to play victims?

To me it’s not victims, just failures. It’s life. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t been a failure. I’m just a human being. I don’t play victims. I play human beings.

Loulou (1980)

I wasn’t suggesting you were consciously aware of playing victims. You just seem to be playing them, that’s all.

I am always in a very psychological movie, always in a humanistic movie. Maybe it wouldn’t be the same if I were in a purely cinematographic movie. I always play in a realistic movie.

Weren’t you supposed to film The Lady of the Camellias at some point?

I just finished it. It was the movie about the real lady who inspired Dumas to write his book.

How does it differ from the myth?

It covers her life from the time she was a peasant girl to when she came to Paris when she was 16 and became a big lady. She died when she was 23.

Another victim.

Oh yes, another victim, but at the same time very strong. What is very interesting is that this story is the symbol of passionate love, but the movie will show something very hard and cold and sad and no love at all. There was no love between her and Dumas, maybe only a guiltiness on his part when he wrote the book about her after her death.

Did you feel at all intimidated in approaching the role? It’s a role great actresses and singers have played.

No.

So you’re very happy with it?

Yes, well, I’m very happy with it. I’m always happy with the work I do. It doesn’t mean I’ll be happy with what I see, though.

You’ve worked a prodigious amount since 1971, performing in more films than some actresses do in a career. Are you thinking of taking a break?

I’m thinking of retiring already.

Serious?

No—it’s always a fun time when you’re an actress. It’s a kind of inhuman projection of yourself, even if you don’t bother to see yourself on the screen. Anyway, if you think of a close-up of yourself on the screen it’s 10 times the size of what you are. It’s something crazy. The more you are projected the more you want to go inside yourself.

What about the craft of other actresses?

I’m always impressed by other actresses more as personalities, such as the story of Marilyn Monroe, not by what they do. Each actress, I think, has to deal with some kind of craziness. You have to be impressed.

Can we talk about Heaven’s Gate?

It’s a complete part, a much more physical part as opposed to the others I’ve done. It’s a Western. I am the head of a whorehouse—I never figured myself like that. I ride horses, I shoot a gun, I drive a buggy, I waltz. It’s incredible the things I do in 24 hours. The main part of the story takes place in five days. It’s about the Johnson County Wars, a little event that takes place at the end of the 19th century in Wyoming. It was a war by Americans who had already settled opposing the waves of immigrants, mostly Eastern Europeans. The wealthy Americans hired mercenaries to kill them.

Violette Nozière (1978)

You play an immigrant.

Yes, I play an immigrant. Kris Kristofferson is the moral authority against the people who want to kill the immigrants. The character of Christopher Walken is at first undecided about the situation, but he changes toward the immigrants, mostly through my character because he’s in love with me. There is a triangle between me, Chris Walken, and Kris Kristofferson.

When Michael Cimino approached you for the role…

He saw me in Violette two years ago. He saw five minutes and that’s it.

Did he tell you what quality he saw in you as Violette?

No, but I can guess. I knew he had been looking for an actress for a long time. In the script it would be someone taller, more powerful, but apparently through a physically small and fragile character he wanted to express strength. Through those young big American guys he wants to express the failure of physical strength. The movie wants to express the real strength, the real stream of life, through the immigrants. The other values—power and money—aren’t the real values at all. The movie is a hard vision of America, and that’s what it wants to be.

It struck me when I saw the cast for Heaven’s Gate there was only one female part in it, similar to Cimino’s The Deer Hunter. That part was played by Meryl Streep. There are times on the screen when you remind me of her.

Oh, that’s a compliment. She’s really the actress I like best in the world now. I think she’s extraordinary. Also there is a similarity in the sort of triangle between her, De Niro, and Chris Walken and the one between me, Kris Kristofferson, and Chris Walken in Heaven’s Gate. Except it’s even more developed. It has the same ambiguity, deepness, and sensitivity. There are many common parts in the way he treated the two triangular relationships.

He’s a very private man. What, on reflection, interests you most about what you’ve done as an actress?

Everything. I really can’t give an answer. What interests me is the value of working with Godard, Cimino, then in Italy. It’s all so different.

Do you have a favorite role?

The favorite role is always the last I did. So far it’s The Lady of the Camellias.

One last question. It’s a quote from Godard: “Her fresh-scrubbed face conceals the soul of a streetwalker.”

What did he say? Is it a compliment? Or an insult?

I suspect it’s a compliment. What do you think he might have meant?

I don’t know. Maybe it’s the same line as what I was saying about what Cimino saw in me: to reveal something completely unexpected. In Godard’s movie, you know, the character, he does not judge her, except the situation she’s going through. She is apparently fresh-scrubbed, yet she suffers an indifference to everything that surrounds her. Also, this indifference is beyond despair—more than despair. Not being able to feel anymore.

Is there anything we haven’t touched upon?

Certainly. There always is. There always will.

Visit our store for more great interviews, reviews, and features from over 55 years of Film Comment.