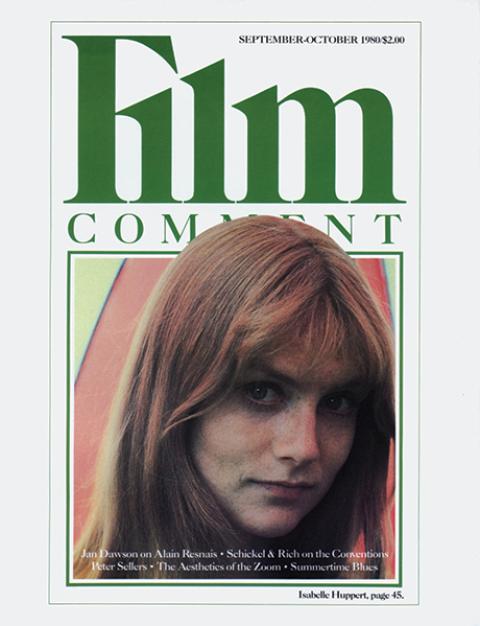

By Dan Yakir in the September-October 1980 Issue

The Mind of Cinema Novo

Toward a new Latin cinema

In 1980, the Brazilian cinema is staging a dramatic comeback, the like of which has not been witnessed on or screens since the days of the Cinema Novo in the early Sixties. Then, with such landmarks as Glauber Rocha’s Terra em Transe and Antonio das Mortes, Ruy Guerra’s Os Fuzis and Nelson Pereira dos Santos’ Vidas Secas, and intensely original, vibrant cinema was born.

From the September-October 1980 Issue

Also in this issue

One of the Cinema Novo’s founding fathers and perhaps its most interesting exponent is Carlos Diegues who, with eight films in seventeen years, has come up with three masterpieces: Os Herdeiros (The Inheritors, 1969), Joanna Francesca (Joanna the Frenchwoman, 1973) and Bye Bye Brasil (1979). Like Louis Malle, Diegues doesn’t fit easily within the auteur theory—not because he doesn’t have a consistent style, but because he allows it to evolve and develop in unexpected directions. While his moods and visual landscapes keep changing, themes, images and concerns constantly assert themselves in his work. Like Malle, he can trace the origin of a picture to an image or idea; like him he favors a musical construction of films and needs music—as an inspiring, directing force—while writing a script. Like Malle, he also seems to seethe with unending anguish while trying to restrain its expression, out of pudeur. But his Brazilian temperament often cancels this very urge and the pain explodes with tremendous energy that seems to parallel Bernardo Bertolucci.

These contradictions are mostly evident in Os Herdeiros and Joanna Francesca, where his pessimism about national and private issues, respectively, is emphatic but where lyricism and a stunning sense of spectacle conspire to convey sheer exhilaration. It is the same exhilaration that one feels in watching the bubbly Xica de Silva (1976), the humorously dramatic exploits of a liberated female slave, or in Bye Bye Brasil, where the humor is less persistent and the pain mitigated by a new, mature acceptance of an imperfect existence.

But while Os Herdeiros and Joanna Francesca (with an investigation of incest, insanity and death) weren’t successful at the box-office in Brazil, most of Diegues’ work has a popular following in his homeland. With the five million admissions won by Xica de Silva, he is certainly the most commercially viable filmmaker of his generation.

In 1980, Diegues with reintroduce himself to American audiences with Chuvas de Verão (Summer Showers, 1977), which has already been released; Bye Bye Brasil, which ash shown in Cannes and is a New York Film Festival selection (it opens in early 1981), and Joanna Francesca, which is scheduled at the Public Theater.

How would you describe the state of Brazilian cinema today and how has it evolved since its inception as the Cinema Novo?

What one calls the Cinema Novo was nothing less than the establishment of modern cinema in Brazil. It wasn’t a school or an aesthetic movement, but simply a reunion of certain young filmmakers who decided to make films that deal with Brazilian problems, a revelatory cinema made in a modern way. This is clear now, twenty years later, when you see that each director went his own way, in a very précis direction. Today you can’t talk about a Cinema Novo or even of a group of filmmakers, but rather of a Brazilian cinema hat produces close to 100 films a year, by good and bad directors alike.

The history of modern cinema in Brazil can be divided into three periods: the first is the Cinema Novo. There was no Brazilian cinema prior to its birth, only a need to invent an image for Brazil—an audio-visual dimension that it didn’t have. You have to understand the cultural colonization of Brazil at the time: before Ganga Zumba [1963], I made a short about a school of samba, which is an organization in the Rio slums that gathers people to dance the samba. It was a complex organization and I wanted to show through it how people organize. I lived with them in the slums for a few months in 1961 while I shot the film. When it was ready, I screened it for them. They said, “This is very nice, but it isn’t cinema.” Cinema for them was the Western, French blondes, the Samurai—because the Brazilian image had never appeared on film before. That’s the achievement of the Cinema Novo: showing what was happening then, allowing the Brazilian people to look at themselves on the screen for the first time. And each director chose his own way of recording this human and physical geography—be it the baroque, epic films that Glauber Rocha shot in the Northeast or the poetic realism that Nelson Pereira dos Santos applied to urban settings.

The second period begins in 1968, with the coup d’etat and the ensuing dictatorship, violence, torture, censorship. From that moment, there started a period that I call “the aesthetic of silence.” Toward the end of the first period, we were trying to reflect upon the role of the intellectual in Brazilian cinema—in films like Terra em Transe, Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s Macunaima, Os Herdeiros—but this reflection was completely obstructed by the regime. So, we had to express ourselves via metaphors, allegories, and symbols. We said as much as we could. It was one of the most beautiful moments in the history of the cinema de résistance in the world, because we didn’t look at things complacently. Nor did we content ourselves with lamenting the situation. We created a language out of this very repression.

This period continued till 1975-6, when a new political openness began, a certain liberalization of the regime, which isn’t the democracy of my dreams but still a step forward. The torture, repression and censorship are almost entirely gone and films like Z, which were banned for many years, are now shown and doing very well.

From 1976 on, Brazilian cinema started regaining its voice. I don’t know exactly what will happen, but things are moving. Young directors are making their first pictures and, most importantly, for the first time quality films are finding their audience—and doing well—which is exactly what the Cinema Novo wanted: to be a popular, national cinema. You have to get the people into the theater, not only show them on the screen. So, once again, we have a renaissance of Brazilian cinema.

It seems that the wild, ecstatic rhythms and the nervous energy of the Cinema Novo have now been replaced by a mellower, less urgent mood.

In the beginning, there were very few of us, maybe eight or nine. We were always together and each of us served as mouthpiece for the others. Everything we said was exactly what the others thought. Now it’s different. There are more of us and I’m no longer speaking for the others. I think that it’s not that Brazilian cinema has become less energetic—it’s still personal and experimental—but now it has its public. The energy that was once found in the formalistic quest is now part of the dialogue between the film and the public.

How was the Cinema Novo born and why did it emerge when it did?

It was a coincidence. I asked Louis Malle a similar question about the birth of the New Wave, because there was the Cahiers du Cinema group, but there were also people who had nothing to do with it, like Malles and Resnais. And he said, “The nouvelle vague is an invention of Arriflex and Dupont, because the former manufactures a lightweight camera and the latter the 3x film, which I very sensitive. Because of these, we could make films cheaply, in the street, with no great compromises.” It’s amusing, but it makes sense.

In Brazil, I think it’s similar. It happened during the regime of Kubitschek, when everyone believed that Brazil was about to take off. Things were easier to do. The explosion of TV took place in the Fifties and whatever film industry there was was incorporated by it. So, the time was right.

There were three groups in Rio: the Cathoic University group, which included Arnaldo Jabor and myself; the guys from the federal-run university, like Leon Hirszman; and those who came from Bahia, like Glauber Rocha. We all met around the Museum of Modern Art, where we founded the first cinématheque in Rio. We started to create the Cinema Novo. But the movement was born before the films, unlike the New Wave, which was proclaimed once the films were shown. I was writing for newspapers, as were Glauber and others, and we were already talking about a movement. In 1960, I remember reading an article by Miguel Borges which declared: “The Cinema Novo is dead!”

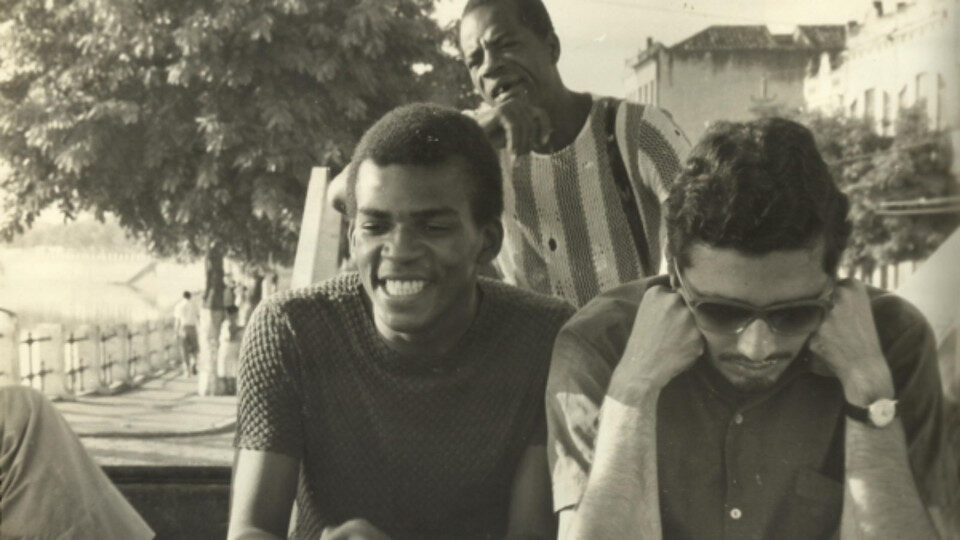

Ganga Zumba 1963

How did you actually start making films? And how do you feel you have evolved?

When I look back at my films, I’m very proud of them—mostly because each of them, whether good or bad, corresponds to a moment in my and my country’s history. It’s a coincidence of biography and history.

I started making films in 1962-3, with Ganga Zumba, while I was a student. It was a fantastic, euphoric period, which corresponded to prima della rivoluzione—before the coup d’ etat. It witnessed the emergence of the new Brazilian music, the bossa nova, the new theater…We were completely sure we were going to change the country with our films, that they had the power to change the world.

But it was a cinema of illusions. In 1968, we realized that this was impossible: we made a revolutionary cinema that went in one direction while society went in another. It made me ill; I was desolate and depressed. And out of my reflection came Os Herdeiros, which tries to examine the role of the intellectual and the artist in society, to understand what can be done. I had a “sick” period. Not that I preferred the “sane” one: I was really in love with death, frustration and this film, like Quando Carnaval Chegar [When Carnival Comes, 1972], corresponded to my feeling that there was nothing left but death.

Now I feel much better. I know that cinema can’t change the world, but I still feel that it’s the most important means of expression in this century, because it directs itself to the emotions and the unconscious of the people. Cinema has changed not the world, but the way of understanding the world in this century. And I’m convinced that someone like Godard is as important as Sartre. A Godard film is more important than a painting by Monet.

But cinema has played this role when made in a relaxed manner, as a personal manifestation of feelings and ideas. Not films made as theoretical tracts, or as entertainment—these have always been bad. I don’t think that the movie theater is a classroom, nor is it a torture chamber. That’s why I feel increasingly better about the cinema, more at ease, because I no longer have theories or preconceptions. I try to surprise myself with each film. And I make films because I love it and because I want to know others and allow them to know me by getting to know themselves a little better.

I no longer want to prove anything, just to express how I feel about the world. It’s much less “aristocratic,” much less repressive in the sense that when you try to prove something you become a leader, a guide—as if you were informing people of what they ought to do. I don’t want it anymore. I just want to be one among many. That’s what cinema is about.

It’s clear from all this that you think of all cinema as political.

Absolutely. But what’s political is the fact that cinema has changed our way of looking at the world, not the power relationships portrayed in the film. A film like La Fievre Monte a El Pao was about such power relationships and it’s very interesting, but Buñuel’s less explicit presentations are no less illuminating.

Why did you choose to make your first film about a black? Did you, as part of the effort to create a Brazilian screen image, try to shock, to go all the way back to the “roots”?

Maybe, yes. I’ve always been interested in black culture. It’s the element that has completely modified Brazil, which otherwise would be a mere cultural colony of Portugal and Spain. Black culture gave us originality. In Ganga Zumba, there’s a metaphor: black culture, with its sensuality and pagan-like religion, is liberating. Instead of one oppressive God, it features many. It chronicles the first popular revolution in Latin America—in fact, in the entire continent- the revolution of the black slaves in Brazil in the seventeenth century.

The principal theme of all my films is freedom and how to exercise it. In Ganga Zumba, it’s the simplest level: how to escape slavery.

And Xica da Silva?

Ganga Zumba is a film about the love of freedom; Xica is about the freedom to love. Ganga Zumba is a programmatic, collective vision pertaining to the question of how a group can strive for it. Xica shows every time you try to liberate yourself you fail, because it’s not a personal matter for Superman to solve. Xica is the true story of a black girl in the eighteenth century who tries to attain her freedom without concern for the others. But she can’t; it’s not a solitary quest. I don’t condemn Xica—I love her—but she made a mistake.

I think that what happened to the hipies in the Sixties is a modern tragedy. They were people who tried to create an alternate society—which is impossible, because people won’t let you. In all my films there’s this kind of statement: there’s society and there’s you. And at the same time that you shouldn’t try to change the regime to get an orgasm, you should always seek pleasure while knowing that you won’t get it without help from the others. This is what my films are about—pleasure and complicity with the others.

Where does the operatic tone in some of your films—most notably, Os Herdeiros—come from?

I don’t know anything about opera and I don’t really like it. I always have arguments with Bernardo [Bertolucci], who adores it.

I was born in a poor, remote region in the Northeast, Alagoas, and it’s there that I acquired a taste for representation—from the dramatic spectacles of the circus. Before the appearance of the acrobats, magicians, and fire-eaters, there was always a short, dramatic play, about twenty minutes long, with overacting and larger-than-life characters. It was somewhat operatic. And then, I’ve always been moved by the carnival—not the way tourists get to see it, but its true, dramatic, larger-than-life manifestation. The samba always tells a story. The dramatic information I received in my youth came from that.

How did you construct Os Herdeiros? It’s very complex.

Next to Chuvas de Verão, it was the most difficult script to write. It’s paradoxical, because they couldn’t be more dissimilar. But they do have the same construction: that of tableaux. The heroes in both serve as catalysts, as means to explore the other characters. In Os Herdeiros, the journalist [played by Jean-Pierre Leaud] was me. It was a way of getting closer to the characters I wanted to explore. The same goes for Chuvas de Verão.

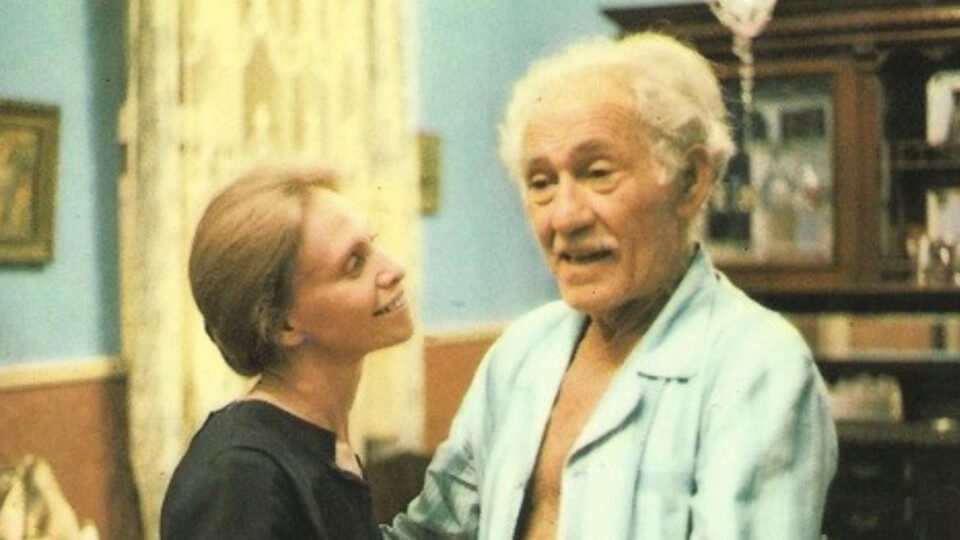

For Os Herdeiros, I had to do a lot of historical and sociological research, because of the period depicted—the Thirties—and then eliminate the unessential and make the character’s personal life coincide with the history of Brazil that engulfed him. the story is very simple. There’s no plot it’s just a look at that man from his youth to his death, and through him, all the characters around him. It was the same with Chuvas de Verão, even through it’s a “chamber film.”

How did you get the idea for Os Herdeiros and Joanna Francesca?

I never thought of doing Os Herdeiros. I wanted to make a film about Getulio Vargas, the dictator who was to Brazil what Peron was to Argentina. I started preparing the film around him but after the first draft I became afraid and felt I couldn’t do it: Vargas changed from a fascist and an early supporter of the Nazis to a man who, in 1950, appeared as a Socialist leader. It was a crazy story. I felt it wouldn’t be understood; it was too arbitrary. He even had Carmen Miranda for a mistress! So I chose instead to make a film about someone who lived in that period.

About Joanna, I’ll tell you a secret. Everything in it either took a place in my family or I had heard my grandfather talk about. He died when I was 14; I was his favorite grandson. One day I just had to make a film about it. I shot the film where I was born. I invented nothing. Even the character of Joanna is based on a real woman: a prostitute from Sao Paulo, who one of my cousins met—and had children with, unlike in the film. After World War I, many French and Polish women came to South America and, among those who became prostitutes in Sao Paulo and Rio, some were very cultivated. In Porto Alegre, the university was founded by a Polish whore. It’s fantastic.

Os Herdeiros 1969

The fact that Joanna is a foreigner seems to be more than just an exotic detail.

In all my films there’s an outsider, a character who doesn’t belong. In Ganga Zumba, the young prince has nothing to do with the other slaves. A Grande Cidade [The Big City, 1966] is about migrants to the city. I don’t know why. It’s not willed. Only now do I understand what I’m doing.

Joanna occurred in the worst moment in my life, and my country’s: I had friends who disappeared in broad daylight or were tortured or went into hiding. Joanna is one of my favorite films, but it’s very “sick.” It’s about my “sickness,” about death. It’s a film where each character chooses the moment of his death, which is bizarre and hard.

How does using the “road movie” format help you state all these themes in Bye Bye Brasil?

I started thinking about Bye Bye Brasil when I was shooting Joanna. It was shot under very difficult conditions: it was the middle of a very hot summer. Jeanne Moreau wasn’t free at any other time, and we had to shoot very quickly because she had to return to Europe. Unfortunately, the production wasn’t well-organized.

One day, we returned to the tiny village [5000 inhabitants], where we were staying. I was completely tired and miserable, but my curiosity was aroused when I saw a strange blue light in the village square. It was a television screen and the people—the sugar cane cutter, the small functionary, etc.—were watching a program from Rio that featured elegantly-dressed people with modern cars: the emblem of consumerism. I was completely amazed and felt I had to film. This was the first image of Bye Bye Brasil, in 1972.

I felt that Brazilian cinema found itself amidst a certain claustrophobia. Gone were the wide, open spaces of Antonio das Mortes, Ganga Zumba, Os Fuzis, and Vidas Secas. It had become a cinema trapped in apartments and urban malaise, and I felt it was time to shoot out in the open. In Rio, one knows little about the interior: the Amazon or the Nordeste. A film like Bye Bye Brasil is a surprise, even a scandal, when shown in the big cities—while in the periphery, they do know about the big centers. I traveled several times across the country, which is enormous, because I realized I didn’t know it at all. So, in the film too, there’s a trajectory from the Northeast to the Amazon to Brasilia.

And in terms of character development?

The three main characters—the black fire-eater Andorinha [Principe Nabor], the magician Lord Cigano [José Wilker] and the dancer Salomé [Betty Faria]—are characters from my childhood, from the circus, the caravana. The young couple [Fabio Junior and Zaira Zambelli] is completely invented: they’re “normal” people. Salome and Cigano are always in the process of representing. They wear make-up even they don’t give a show. They’re always “on stage” while the young couple watches and observes. These are two ways of responding to reality. I like the pregnant young woman, because she’s really modern, very objective, with her feet on the ground. Her husband is a romantic, but he’s “normal.” The magician and the dancer, on the other hand, has no rapport with reality. It’s pure fantasy.

It’s this dialectic that provides us with the balanced view that we get. I chose these caracteres de spectacle, because I wanted to look at this film with the eyes of an artist rather than a sociologist or a political scientist.

We shot the picture like the navigators of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, who came from Europe to the new continent without knowing what to expect. We tried to give a personal impression of what we saw. We were a tight community. The actors helped a lot, especially José Wilker, who’s a playwright, an intellectual, and a friend. It was a discovery for everybody.

Bye Bye Brasil is a film about everything that happens along the way. The peasants, the prostitutes, the Indians, the projectionist are no less important than the principal characters.

If this is a film about discovery, then Chuvas de Verão is about letting skeletons out of the closet. How do you see the film in view of the claustrophobic cinema you have discussed?

It corresponds to the period, but it’s no longer a “sick” film. It’s a film of recovery.

I made it as a reaction to Joanna Francesa. Chuvas de Verão is about a moment of happiness that one has to savor rather than become fatalistic and accept death. What will be will be, but one shouldn’t seek it. In that sense, it’s an optimistic film, almost Walt Disney—because it tells the story of people who ruined their lives because they attributed too much importance to insignificant details. And at the same time it’s about the “double-ness” of life: you never know your parents, friends, neighbors. They’re never what you think they are.

Chuvas de Verao 1978

Which is why you didn’t develop a confrontation between the hero [Jofre Soares] and the terrorist who hides in his house: that’s another story.

Absolutely.

What was A Grande Cidade about?

It’s about four men who come from the northeast to Rio. Today Sao Paulo is the more mythical city, and back when it was Rio; they thought streets were paved with gold. These outsiders arrive and try to understand what goes on. It’s also a film about complicity. It shows that people have to help each other, because otherwise we’re completely in the shit—social, economic but mostly in the sense of lack of affection and tenderness.

Like Chuvas de Verão, it’s a “chamber film,” it’s very simple. It’s not pessimistic, but maybe melancholic in the sense of regretting that things aren’t what we want them to be. Anyway, two of the characters die, one returns to the northeast and the main character, the same black actor who played in Ganga Zumba [Antonio Pitanga] decides to stay and the film ends with him dancing.

In a way, it’s the birth of Xica—because he understands that for all the suffering and derision, he has to survive.

And Quando Carnaval Chegar?

Quando Carnaval Chegar wasn’t understood at all when it came out. It’s one of my least popular films. Today, curiously, it’s often shown on TV and people start to get the point. I understand why: it was very difficult to watch it at the time. The principal characters were popular singers—Chico Buarque, Nara Leão, and Maria Bêthania—and people went to the theater to see a cheerful musical comedy. Instead they got a very sad film about frustration, defiance and perseverance.

How do you use music in your films? For example, in Xica da Silva the title song appears on the soundtrack as the director’s comment only to be repeated later by one of the characters humming it as part of the action. It’s multi-layered.

Music evidently plays a very important role in my films. Sometimes it’s born at the same time as the film. It’s an inherent part of it. In Os Hedeiros there’s a song by Villa-Lobos that was written in 1943. I always had it in my head. When I write a script, I see in my mind the images of the actors’ heads and hear the songs I’m going to use. Even if I end up not using them, I write thinking about them. I can’t write otherwise.

All my films are either musical or have a musical construction. It’s never decorative or used to underline the action. It has an important dramatic role, it adds new information. In Os Herdeiros, we told the history of Brazilian music in the last forty years on the soundtrack. We used a song to represent each year in that historical tableau, so you could see the film with closed eyes—because story is repeated on the soundtrack.

Could you trace the influences on your work—and the Cinema Novo—then and now?

The New Wave was more an alliance than an influence on us. It was a kind of model. It wasn’t the films themselves so much—even though I was always always taken with Godard—but the principle.

What influenced us enormously was the American cinema, which we’ve known since our childhood. Aside from the Neo Realism, we weren’t all that familiar with European cinema.

Personally, I love John Ford and Howard Hawks. I first saw their films and only later went to the library to read about them. It was an education more cinematic than literary. Maybe for the first time there was in Brazil a generation that had a visual culture. We’re also influenced by Brazilian writers—especially the modernists of the beginning of the century—but it was an influence after the fact.

I don’t know what influences me today. I can trace my influence in the films of Arnaldo Jabor, of Glauber in my films, and of Nelson Pereira dos Santos in those of Joaquin Pedro de Andrade. We influence each other and there’s a younger generation that’s greatly influenced by the Cinema Novo.

Today, we need to create a Latin cinema—but not in the ethnic or racial sense. Unlike the Europeans, whose culture is petrified, we need to build rather than destroy. And what I envision is a cinematographic body in which Renoir is the head, Rossellini the heart, and Buñuel the gut.