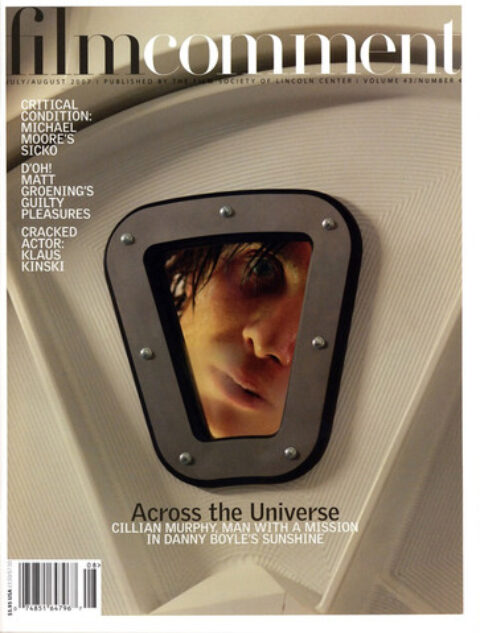

By Chris Darke in the July-August 2007 Issue

Sweet Bird of Youth

Why Kes, Ken Loach's tale of a working-class boy who raises a kestrel, is an English classic

The British are weird when it comes to children, and never more so than now. On the one hand, the little treasures must be plied with the latest consumer goodies while being kept safe from the current bogeyman, the pedophile, who, judging from recent media panics, lurks around every street corner. On the other hand, the child is also a feral little thug good only to be served with an Anti-Social Behaviour Order or banged up in a Young Offenders Institution. It’s not hard to see how my (barely exaggerated) sketch might fit with the long-standing class divisions of British society. Today, a character like Billy Casper in Ken Loach’s Kes would fit the latter characterization—broken home, no educational achievements, 14 years old, and not a hope in hell.

From the July-August 2007 Issue

Also in this issue

Except one, perhaps. In the woods near his deprived northern mining-town home, Billy (David Bradley) finds a kestrel chick that he names “Kes” and lovingly rears and trains. The bird is all the boy’s got, the only thing offering the vision of a horizon beyond a tough home life with his uncaring miner brother Jud and their old-before-her-years mother and the institutionalized brutality of school. “He’s a hopeless case,” says his mother of her youngest, and she’s not wrong. A malnourished shrimp in his brother’s cast-offs, Billy’s a misfit among his classmates, the butt of jokes and bullying. The character could so easily have become the focus of sentimentalized pathos, but Loach, in his faithful adaptation of Barry Hines’s perennially popular novel A Kestrel for a Knave, avoids this completely.

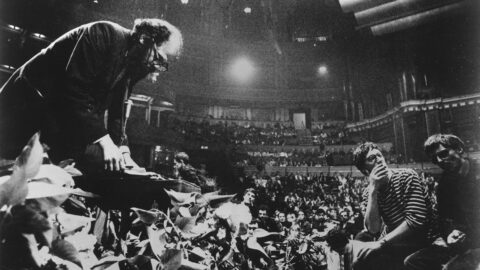

Made in 1969, Kes was shot on location in the Yorkshire mining town of Barnsley with a cast largely made up of locals and nonprofessional actors. Kes remains one of Loach’s best-loved films—it was his second foray into feature filmmaking after his debut collaboration with producer-writer Tony Garnett on Poor Cow in 1967, which followed a period in which he made agenda-setting dramas for the BBC such as Cathy Come Home (66). His hallmark traits of effortless naturalism and unpatronizing attention to working-class lives are on show here, fully formed and deeply affecting. The extraordinary performance of the nonprofessional Bradley as Billy is the film’s heart: he’s simultaneously as earnest, lively, and distracted as any 14-year-old but also resourceful and completely aware of his hopeless circumstances. There’s a beautiful scene near the end of the film when Mr. Farthing (Colin Welland), the only teacher who shows any faith in the boy, visits him in the shed where Billy keeps the kestrel. Observing the bird, Billy says, “I think she’s doing me a favor just letting me sit here and watch her,” revealing a mature respect for the creature that impresses his teacher.

One of the film’s most striking features is its pastoral moments, especially when Billy ventures into the countryside and first spies the kestrel. Abetted by a very late-Sixties soundtrack of strings and trilling flute, the natural light and dappled textures of Chris Menges’s cinematography provide a blessed tonal contrast to the grimly rundown backdrops of the rest of the film. With his abiding interest in social institutions and the ways in which they crush individuals, Loach isn’t usually associated with bucolic poetry, but I defy anyone to watch the kestrel-training sequences in Kes and not be impressed by the way the director conveys the uplift of Billy’s communion with nature. They can’t help but remind one, too, of British cinema’s perennial lack of imagination in the face of its most criminally underexplored resource, the varied beauty of the island’s natural landscapes.

Of course, Kes is more than simply a pet for Billy; the creature is also a symbol of hope. Billy’s increasingly obsessive attention to the bird leads him first to educate himself in the techniques of falconry, albeit with recourse to petty theft. After the local library proves predictably obstructive, Billy—adroit half-pint that he is—liberates a volume about training birds from a secondhand bookstore. Throughout the film, others make much of Billy’s barely literate state, but Loach offers us evidence to the contrary. Over footage of the boy’s patient coaching of Kes, we hear Billy narrating the process from his book, and we realize that this is no dullard but a misjudged child with a rich interior life. This becomes clear in a central scene when the sympathetic English teacher Mr. Farthing encourages Billy to talk about Kes in class and the boy opens up with expert enthusiasm. The bird has led him from books to public articulacy. It’s a triumphant moment and, to emphasize this, the camera homes in close on Billy and his classmates, who listen with rapt attention. But Loach leaves us in little doubt just how short-lived this epiphany of hope will be in the larger scheme of things. In the following scene, Billy is once again being bullied in the playground by one of those same classmates, the ensuing fight tellingly set atop a slag heap of coal.