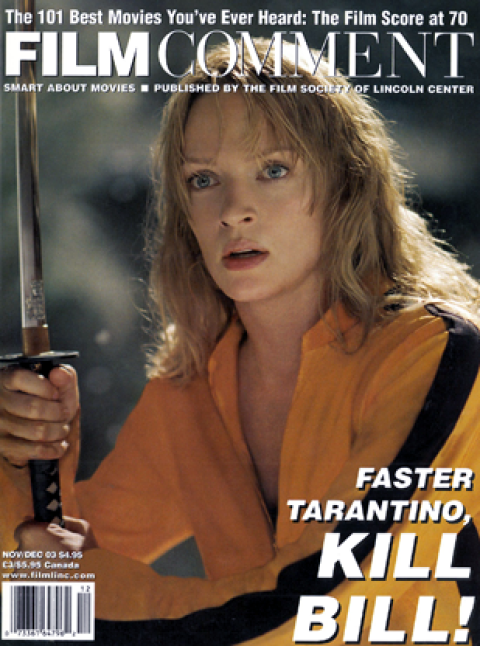

By Geoffrey O’Brien in the November-December 2003 Issue

Devotional Furies

As everyone knows, Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill has been sliced in two. We thought of publishing one half of our coverage in this issue, and then making you wait a couple months for the climax. Instead, we’ve opted for mercy, compassion, and forgiveness, and unleashed two of our best writers on Volume 1—after all, two heads are better than none

If the video rental store is a pharmacy of desires, the video clerk is the obscure scientist who has tested all the potions on himself, poisons and elixirs alike. Has he grown strong in the process, or terminally jaded, or perhaps fatally attached to the objects of his vision? Imagine that he goes home and dreams a dream in which the videos mingle and mate with one another: a cast of Japanese gangsters in wraparound shades, women held captive by sadistic South American prison wardens, female vampires and maimed martial artists, Mexican wrestlers and Italian serial killers, avengers of the Western plains accompanied by pan flutes and a chorus of whistlers, swarming multitudes escaped from Suspiria and Shogun Assassin and The Street Fighter’s Revenge, all of them asserting the ferocious tenacity of ghosts, demons, and tutelary spirits. He wakes to find himself transformed. The unknown that was imbued with dread and strangeness is now irredeemably part of him, a language without which he can barely state who he is.

Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill is a movie conceived in such a language. If the superb Jackie Brown seemed to move in the direction of real worn-out spaces and real elegiac feelings, Kill Bill Vol. 1 marks the return with a literal vengeance of Tarantino the demonic video store clerk, enamored of the grainy unrecoverable epiphanies of lost drive-ins and Chinatown movie theaters and all-night gore fests. It’s a love poem, but the kind of love poem that makes you wonder if you want to go out with the person who wrote it, or that at least makes you wonder if by responding to it you won’t become complicit in a liaison that will leave deep scars. Scars are everywhere here, and blood, much blood, blood dripping or splattering or geysering or congealing or turning a pool of water bright red, elicited often by dismemberment and decapitation, and invoked often enough to become ornamental, a floral decoration on the envelope of the love letter.

And to whom is the love letter addressed? To Uma Thurman, the battered, bleeding bride transformed into an avenging swordswoman, who dominates the screen at almost every instant, hurling imprecations in English and Japanese and lunging forward to deliver one more savage slice with an impressive air of total conviction? (Thurman deserves a prize, if not for acting then for endurance.) Or are we in the realm of allegory, where the splendid isolated figures of women (Daryl Hannah, Vivica A. Fox, Lucy Liu) represent not, as in the middle ages, Prudence or Charity or Wisdom but rather Kung Fu or American International or Chambara or Blaxploitation, those eternal categories of the mind? From the opening frame (the old ShawScope logo of beloved and recently revived memory), the genre formulas that Tarantino so lovingly re-enacts and expands upon are not so much in-jokes as traces of sacred ritual, complete with the requisite vestments and liturgy. The jokey obscenities and pop-culture hipsterisms can hardly disguise the fundamentally solemn aura of this entertainment.

It’s a solemnity that threatens to reveal at its center nothing at all. The mass slaughter that Thurman executes in the middle of a lavishly postmodern Tokyo nightclub takes place on a glass floor overlooking a re-creation of a Zen rock garden, scarcely visible among the cascade of severed limbs. That moment, occurring just about at the midpoint of the two-part film, might, I suppose, be its pivot point: the symbolic opposition of bloodshed and nothingness, swirling mayhem and tranquilizing abstraction. Or would the center be, more appropriately, the Japanese all-girl punk band that a few moments earlier belts out a version of the Ikettes’ ãThe Gong-Gong Song,ä just before a simpering uniformed schoolgirl steps out swinging a jagged-edged mace?

To turn a penny arcade into a Zen monastery, or a Zen monastery into a penny arcade: it isn’t that Kill Bill can’t make up its mind but rather that (in what might be a triumph of mystical insight) it no longer has a mind to make up. It has gone beyond all that, leaving only a few martial-arts movie aphorisms to denote the point where meaning vanished once and for all. It is, then, a vision of Hell, if Hell were imagined as a live-action cartoon (or, in the extended anime flashback, a literal cartoon) full of deftly amusing parodies, music of devastating appositeness, bracing color schemes, and dazzling compositions, a cartoon teaching that those who do not assault must resign themselves to being assaulted.

What holds it all together is formalism. The air of flagrant artifice must be sustained, in the first place, to prevent any apprehension that the violence is real. If it were real, then one might begin to wonder why it was really necessary to make—or to see—a movie in which during most of its running time women are verbally abused, raped (albeit off-camera), slapped, beaten, stabbed, and dismembered. Most of the suffering is inflicted by women, as well, of course (although in the background there is always the nefarious Bill). Keep telling yourself that it’s only pastiche. Remind yourself that all the images were already there, in the thousand movies that Tarantino has drawn on; remember how much Chu Yuan had already surpassed him, as regards woman-on-woman mayhem, in the last reel of Intimate Confessions of a Chinese Courtesan. All the same, the director’s relentless enthusiasm for his own private bloodbath can begin to feel like a hobbyist’s mind-numbing guided tour of his collection of rare trading cards.

Tarantino also needs the formalism because this time around he has had to sacrifice a good many of the elements that he’s relied on in the past. The martial-arts genre is, to put it mildly, not primarily reliant on words, and Tarantino signals his adherence to the genre’s requirements in the first scene with an abrupt and nasty set-to between Thurman and Fox in the dining room of Fox’s comfortably appointed Pasadena home. There is little occasion in Kill Bill for the extended verbal riffing of the earlier films, and much of what he comes up with seems thin. The sight of Thurman and Fox yelling “bitch” at each other comes close to dissolving the movie into silliness right from the start, while some outbursts of colorful misogynistic filth from a Texas sheriff and a depraved hospital orderly seem almost desperate attempts to give the fans the anticipated quota of shockers to memorize. There is little real humor except for a wonderful scene between Thurman and Sonny Chiba as a master swordsman masquerading as a sushi chef, in which Chiba hauls out every tired compliment familiar to tourists in Japan (“You say exactly like Japanese”) as if the pointed deployment of such clichés were a species of martial art.

The mere presence of Sonny Chiba is sufficient to summon up a whole world of East Asian filmmaking in relation to which Kill Bill figures as a sort of rogue disciple, like Toshiro Mifune in Seven Samurai. Some elements of the homage kick in early on, especially on the soundtrack during the fight scenes, with their old-time high-definition bone-crunching sound effects. But from the minute Thurman heads off to Okinawa to begin her systematic vengeance on her would-be killers, the movie becomes elated: it is going where it wants to go.

It wants to go to Heaven, Heaven being the aesthetic formalism that can take the form of a brutal murder in exquisite anime stylization, a jetliner flying impossibly low over Tokyo so that Thurman can study the streets from her window seat, a yakuza gang sprung from the demented world of some Seijun Suzuki film, a water dipper clacking down in the foreground of a garden scene to frame the death duel taking place in the background, the streak of blood making calligraphy on the snowy ground. Above all, it takes the form of prolonged murderous swordfights, or rather of a single swordfight that engulfs some hundred combatants in a death struggle with Thurman. Here Tarantino gets in his little joke by showing us, after the seemingly interminable fight is finally over, the shot that the other movies never show: a vast floor space completely covered with groaning mutilated yakuza crawling out over the bodies of their fallen comrades.

It’s hard to imagine where Tarantino can go from there in Vol. 2, but then a certain monotony is to be expected and even welcomed in this genre. Martial-arts movies are not finally about surprise but about the steady, sustaining drone of action that unfolds as if it were a natural phenomenon, a swirl that when observed with the proper detachment can be both invigorating and beautiful. Much as he might want to be, though, Tarantino is not King Hu or Chang Cheh or Chu Yuan, Kenji Misumi or Kinji Fukasaku. Not that he lacks their gifts—Kill Bill confirms him as a filmmaker of astonishing invention and aplomb—but that he lacks their context. A director peculiarly inspired by place, whether the warehouse in Reservoir Dogs or the shopping mall in Jackie Brown or the nightclub in Kill Bill, Tarantino finally needs to invent a cultural space in which his movies can exist. Here he has woven it out of strips of old celluloid, a sort of carnival tent hoisted up in a void: a haunted funhouse for resurrected swordswomen, where they can eternally enact the same unfinished and unfinishable revenge drama.