By Kent Jones in the May-June 2013 Issue

Intolerance

On westerns in general, John Ford’s in particular, and why Quentin Tarantino shouldn’t teach film history

One of my American Western heroes is not John Ford, obviously. To say the least, I hate him. Forget about faceless Indians he killed like zombies. It really is people like that that kept alive this idea of Anglo-Saxon humanity compared to everybody else’s humanity—and the idea that that’s hogwash is a very new idea in relative terms. And you can see it in the cinema in the Thirties and Forties—it’s still there. And even in the Fifties. But the thing is, one of my Western heroes is a director named William Witney who started doing the serials. He did Zorro’s Fighting Legion, about 22 Roy Rogers movies; he did a whole bunch of Westerns . . . John Ford puts on a Klan uniform [in The Birth of a Nation], rides to black subjugation. William Witney ends a 50-year career directing the Dramatics doing “What You See Is What You Get” [in Darktown Strutters]. I know what side I’m on.

—Quentin Tarantino, in conversation with Henry Louis Gates, in The Root

From the May-June 2013 Issue

Also in this issue

Let’s start with the obvious and agree that Tarantino was carried away by his disgust with racism and his lofty feelings about William Witney. Let’s give him the benefit of the doubt and assume that it’s been a while since he took a fresh look at Fort Apache (48) or Cheyenne Autumn (64) or—given the fact that he’s collapsing prejudices against Indians and African-Americans into one—Sergeant Rutledge (60). Let’s assume that such Witney titles as Drums of Fu Manchu and Jungle Girl are as racially enlightened as Tarantino claims Darktown Strutters to be. And let’s assume that, as he was soaring on the wings of his rhetoric, Tarantino forgot that Ford’s own ancestors were not Anglo-Saxon but Celtic, that they were not exactly welcomed with open arms when they started emigrating to this country in great numbers in the 1840s, that the memory of Anglo-Saxon oppression was considerably fresher in Ford’s lifetime than it is now (still pretty fresh back home), and that the Irish experience played no small part in his films.

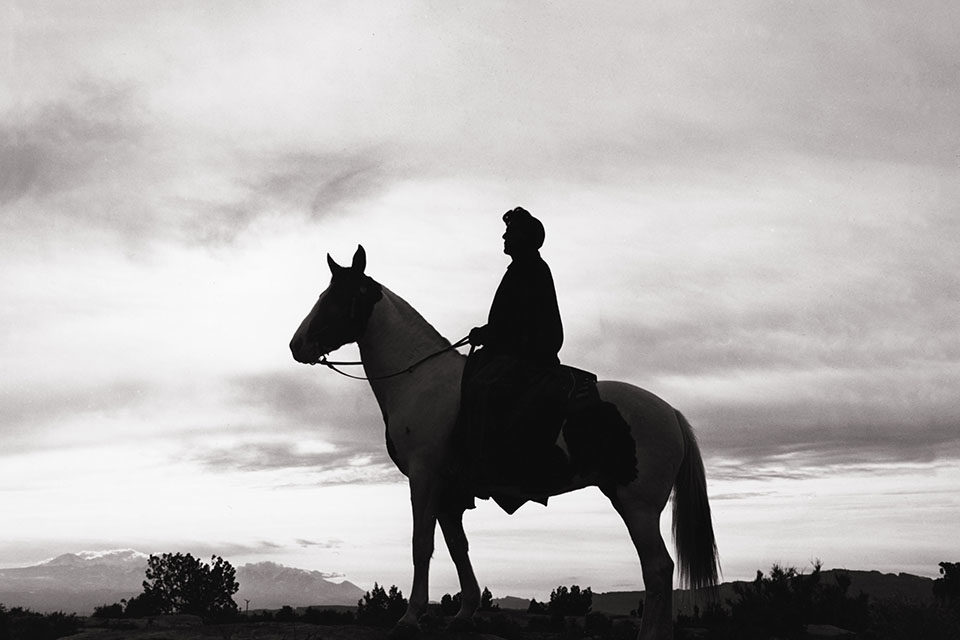

Ricardo Montalban in John Ford's Cheyennne Autumn (1964)

But let’s take a closer look at the part about Ford killing all those “faceless Indians.” First of all, the Indians in Ford’s films, while never as carefully drawn as the Indians in Delmer Daves’s films, are less “faceless” than they are in many other movies made by directors with only a fraction of Ford’s knowledge of the actual West. Secondly, what about all the other directors who killed so many more faceless Indians? What about Hawks (Red River), Walsh (They Died with Their Boots On, Distant Drums, Saskatchewan), Hathaway (The Thundering Herd, Ten Gentlemen from West Point), Vidor (The Texas Rangers, Northwest Passage), de Toth (Last of the Comanches), Mann (The Last Frontier), Tourneur (Canyon Passage), and Sherman (Comanche, War Arrow, The Battle at Apache Pass)? And what about all the lesser directors, the Lesley Selanders and Louis Kings and R.G. Springsteens and lower and lower down the pole? Does anyone actually believe that they each chose Western stories set during the Indian Wars because they unwittingly shared a burning desire to promote the superiority of Anglo-Saxon humanity? Or that William Witney laid down the law with Republic president Herbert Yates and unequivocally refused to make any films about the slaughter of Indians? While making it clear that the Chinese were another matter and that a Fu Manchu serial was okay? On the other hand, he seems to have made an exception for Santa Fe Passage, about an Indian scout played by John Payne who stands up to a murderous band of Kiowas.

Some of these directors wielded quite a bit of power, Hawks most of all. Some of them, like Witney, wielded none and were in no position to refuse an assignment. The fact that he didn’t wind up making that many movies featuring pitched battles between Anglo-Saxon cowboys or scouts or soldiers and hordes of Apaches or Cheyennes or Sioux, gunned down from behind the safety of rock formations or upended Conestoga wagons or on horseback, obviously has nothing to do with personal predilections and everything to do with the reality of slaving away on budgets that didn’t allow for the cost of feeding, housing, and paying 100 horse-riding extras and a couple of dozen stuntmen. Shadows of Tombstone (53) is more typical Witney fare and more typical of low-budget Westerns in general: a rancher catches a bandit who turns out to work for the corrupt sheriff and then decides to run for office himself with the help of the beautiful local newspaper owner.

In some of the above-mentioned cases, the battle with the Indians is nothing more than an episode in a Western saga, as in Red River. In Hathaway’s Ten Gentlemen from West Point, the raid on Tecumseh’s camp is the final step in the military education of the eponymous 10 cadets. In Vidor’s Northwest Passage, the massacre of an entire Abenaki village builds with a scary momentum that suggests (or suggested, to certain post–My Lai viewers) that the film itself was bursting through its own celebratory spirit of the pioneering ethos to reveal a throbbing inner core of American supremacist bloodlust. In Mann’s The Last Frontier and Walsh’s Saskatchewan, as in Ford’s Fort Apache, a hero with extensive knowledge of Indian ways and a respect for a particular Indian tribe (Sioux in the Mann, Cree in the Walsh, Apache in the Ford) comes into conflict with a commanding officer who lives long enough to see his arrogant attempt to assert the superiority of Anglo-Saxon humanity go down in flames. In certain films, the Indians are played by actual Indian actors, albeit often from the wrong tribe (as was the case in many Ford films). In others, including Daves’s enlightened Broken Arrow and Drum Beat, they are played by white actors like Jeff Chandler and Debra Paget and Charles Bronson. From a distance, it’s very easy to view the Western genre as a great abstract swirl of cowboys and Indians, the proud Cavalry vs. the mute savages, a long triumphal march of Anglo-Saxon humanity led by John Ford and John Wayne brought to a dead halt by The Sixties. Up close, one movie at a time, the picture is quite different. Similarly, the mental image of a film about the South at the turn of the century featuring Stepin Fetchit as the devoted manservant of a small-town judge sounds like the occasion for a satisfying round of righteous indignation, while the actual films Judge Priest (34) and The Sun Shines Bright (53) are something else again.

Why would Quentin Tarantino, of all people, buy into such a frozen, shopworn image of Ford and the pre-Sixties Western genre, an image that is now six decades old and more of an antique than anything Ford ever directed? Of the 12 sound Westerns Ford made between 1939 and 1964 (I don’t think that Tarantino is referring to the silents: we’re not talking about actual film history here, but a political construct from an earlier era built around the Cavalry trilogy), some have no significant action involving Indians at all, including My Darling Clementine (46)—unless you insist on counting its one drunken Indian—3 Godfathers (48), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (62). In Wagon Master (50), Ben Johnson is chased on horseback by a band of Navajo warriors, but when they see that he is traveling with Mormons, all hostilities cease—one oppressed people recognizes another. At the Navajo dance to which they’re invited, an outlaw who is hiding among the Mormons sexually assaults a squaw, and the Mormon elder has the man publicly flogged. Since no Indians, faceless or otherwise, are killed, I presume that this is not one of the films that Tarantino had in mind. In Fort Apache it’s Cochise and Geronimo, hardly faceless, who do most of the killing—yet within the framework of the film they are justified because their people have been corrupted by the local Indian agent and their agreements with the American government have been dishonored. In She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (49), in which tensions break out between the Indian agent and a rebel Arapaho leader, the final Seventh Cavalry raid on the Arapaho camp is bloodless and intended to avoid a massacre. Two Rode Together (61) is about the problems of returning white Comanche captives to their prejudiced families. In Sergeant Rutledge, the Ninth Cavalry tracks down and battles with a band of Mescaleros . . . but the Ninth Cavalry is all-black and the protagonist is its proudest sergeant, falsely accused of the rape and murder of a white girl—surely Tarantino could see his way to cutting this one a little slack. In essence, I think that we’re really talking about three movies: Stagecoach (39), in which the men on the eponymous vehicle defend themselves and the women aboard against a band of Apaches; Rio Grande (50), in which Apaches on a rampage are wiped out by the Cavalry on the Mexican side of the border; and The Searchers (56). More about that one later.

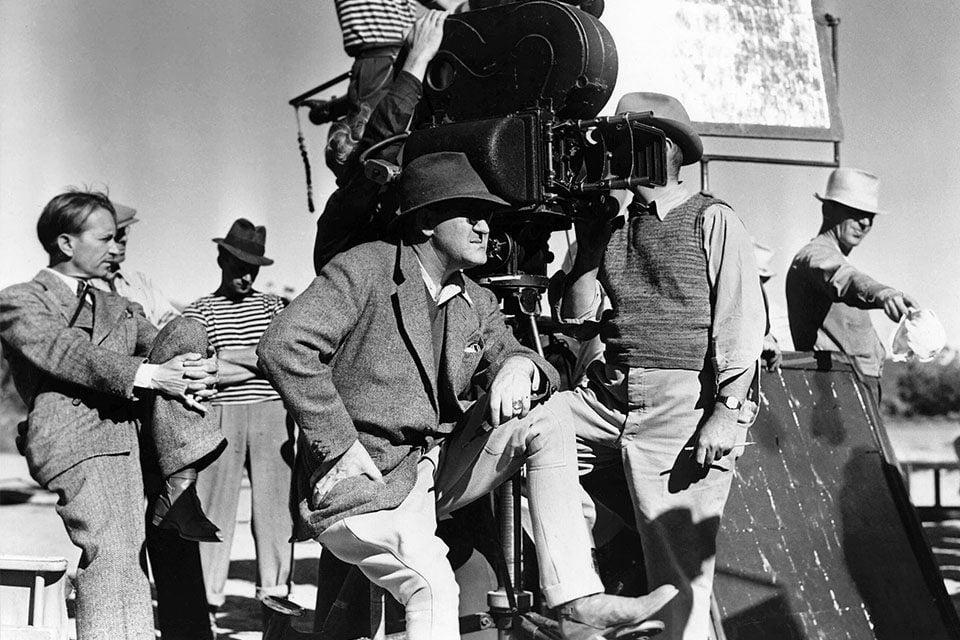

John Ford on the set of Stagecoach (1939)

The idea of the American West was always more a matter of solitude and space and the balance between individualism and community than a matter of conquest. Along with the city as theater of life in the Thirties or bourgeois existence as genteel prison in the Fifties, the idea belonged to no director or writer, and the culture breathed it long before the movies began. That the idea was built on the backs of indigenous Americans who were, in Ford’s own words, “cheated and robbed, killed, murdered, massacred and everything else,” was not exactly hidden from view, but relegated to the background of the story that the culture was telling itself through paintings and dime novels and traveling shows and, finally, movies—albeit never quite as comfortably as is now imagined. It’s curious that American culture and history are still so commonly viewed through a New Left prism, by means of which 1964 or thereabouts has become a Year Zero of political enlightenment; as a consequence, the preferred stance remains that of the outsider looking in, or in this case back, at a supposedly gullible and delusional pre-Sixties America. It’s certainly preferable to right-wing orthodoxy, but that’s hardly a compliment. The New Left is now very old but its rhetoric lives on, many times removed from its original context, and that rhetoric seems to have found a welcome home in film criticism.

Can we really afford to keep saying “them” instead of “us?” Is it useful to keep looking back at the past, disowning what we don’t like and attributing it to laughably failed versions of our perfectly enlightened selves? Should we really give ourselves the license to remake film history as we would like it to be by eliding certain details and amplifying others—in this case, selling The Birth of a Nation as the American equivalent of The Eternal Jew, equating a day of extra work with riding for the real Klan, elevating William Witney to King of the Underdogs and sweeping John Ford into the dustbin, and maintaining that the Blaxploitation genre was a model of African-American empowerment? Why do we keep insisting on the de-complication of history if not to justify our own tastes and abolish our discomforts? The Birth of a Nation is indeed a hair-raising experience, and its moments of visual poetry, as stirring as ever, are as close to its many truly repugnant passages as teeth are to lips, to paraphrase Mao. They always will be. Does that oblige us to pretend that the film wasn’t a beacon for every director of Ford’s generation and beyond, for fear that we might appear racist by doing otherwise? Griffith and Thomas Dixon, with assistance from Woodrow Wilson, helped to reinvigorate the real Klan. They did so unwittingly, not with a piece of propaganda but with a powerfully dynamic and romantic rendering of the “old South” of their elders that housed a racist deformation of history at its core—indeed, if they had been mere propagandists like Fritz Hippler or Veit Harlan, their film would never have had the effect that it did. That’s not splitting hairs, but the thorny, unwelcome, complicated truth. The question is, how do we live with it?

A scene from The Birth of a Nation (1915)

And how do we live with John Ford? Just as a great deal of energy once went into the domestication of The Birth of a Nation—for instance, James Agee’s contention that Griffith “went to almost preposterous lengths to be fair to the Negroes as he understood them, and he understood them as a good type of Southerner does”—so an equal amount has gone into smoothing out Ford, fashioning him as either a drunken-racist-militarist-jingoistic lout with a gift for making pretty pictures or a Brechtian political artist. If I have some sympathy for the latter position (and zero for the former), it still seems like a stretch. But as Raymond Durgnat might have put it, and as Jonathan Rosenbaum argued so eloquently in his 2004 appreciation of The Sun Shines Bright for Rouge, Ford wasn’t a great artist in spite of the contradictory imperatives of his films but because of them. His films don’t live apart from the shifts in American culture and the demands of the film industry, but in dialogue with them. Do those films provide the models of racial enlightenment that we expect today? Of course they don’t. On the other hand, they are far more nuanced and sophisticated in this regard than the streamlined commentaries that one reads about them, behaviorally, historically, and cinematically speaking, and the seeds of Ulzana’s Raid and Dead Man are already growing in Fort Apache and The Searchers. Is Ford’s vision “paternalistic?” I suppose it is (and that includes The Sun Shines Bright and Sergeant Rutledge), but the culture was paternalistic, and holding an artist working in a popular form to the standards of an activist or a statesman and condemning him for failing to escape the boundaries of his own moment is a fool’s game. Maybe it’s time to stop searching for moral perfection in artists.

The mistake has always been to look for the paternalistic, find it in Ford’s work, and then make the leap that it is merely so. If there’s another film artist who went deeper into the painful contradictions between solitude and community, or the fragility of human bonds and arrangements, I haven’t found one. To look at Stagecoach or Rio Grande or The Searchers and see absolutely nothing but evidence of the promotion of Anglo-Saxon superiority is to look away from cinema itself, I think. In Stagecoach and Rio Grande, the “Indians” are a Platonic ideal of the enemy—every age has one, one can find the same device employed throughout the history of drama, and in countless other Westerns. As for The Searchers, the film becomes knottier as the years go by. The passage with Jeffrey Hunter’s Comanche wife Look (Beulah Archuletta) is just as uncomfortable as the courtroom banjo hijinks in The Sun Shines Bright, particularly the moment when Hunter kicks her down a sandbank—but the comedy makes the sudden shift to relentless cruelty, and the later discovery of Look’s corpse at the site of a Cavalry massacre of the Comanches, that much more shocking.

Tarantino’s ill-chosen words more or less force a comparison between his recent films and Ford’s. As brilliant as much of Django Unchained and Inglourious Basterds are, they strike me as relatively straight-ahead experiences—there is nothing in either film to de-complicate; by contrast, one might spend a lifetime contemplating The Searchers or Wagon Master or Young Mr. Lincoln (39) and continually find new values, problems, and layers of feeling. And while Tarantino’s films are funny, inventive, and passionately serious about racial prejudice, there is absolutely no mystery in them—what you see really is what you get. Within the context of American cinema, Django is a bracing experience . . . until the moment that Christoph Waltz shoots Leonardo DiCaprio, turns to Jamie Foxx, and exclaims: “I’m sorry—I couldn’t resist.” The line reading is as perfect as the staging of the entire scene, but this is the very instant that the film shifts rhetorical gears and becomes yet another revenge fantasy—that makes five in a row. Is revenge really the motor of life? Or of cinema? Or are they interchangeable? Or whatever, as long as you know what side you’re on?

If Waltz’s admission of the irresistible impulse to take vengeance on the ignorantly powerful is the key line in Django Unchained, the key line in The Searchers, delivered in the first third of the film, is its polar opposite. As Jeffrey Hunter’s Martin and Harry Carey Jr.’s Brad prepare to join John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards on his quest to find his nieces, Mrs. Jorgensen (Olive Carey) takes Ethan aside and pleads with him: “Don’t let the boys waste their lives on vengeance.” Ford’s film is about the toll of vengeance on actual human beings, while Tarantino’s recent work is about the celebration of orgiastic vengeance as a symbolic correction of history. Ford’s film has had a vast and long-lasting effect on American cinema, while the impact of Tarantino’s film has, I suspect, already come and gone. But then, Ford only had the constraints of the studio system to cope with, his own inner conflicts aside, while Tarantino must contend with something far more insidious and difficult to pin down: the hyper-branded and anxiously self-defining world of popular culture, within which he is trying to be artist, grand entertainer, genius, connoisseur, critic, provocateur, and now repairman of history, all at once. It makes your head spin. And one day in the future, I suppose he might find himself wondering just what he had in mind when he so recklessly demeaned one of the greatest artists who ever stood behind a camera.

Editors’ Note: The print and original on-line version of this piece incorrectly identified Olive Carey’s character as Brad’s wife. The mistake has been corrected in the online version.

Kent Jones is Film Comment’s editor-at-large.

Visit our store for more from from 55 years of Film Comment.