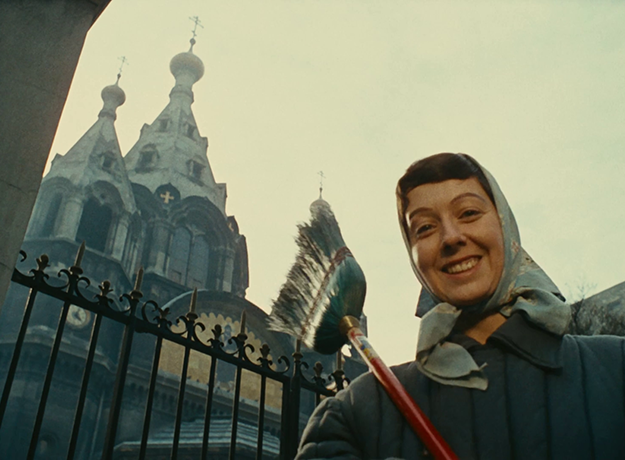

Letter from Siberia

“It’s pretty rare to be able to take a walk in an image of childhood.” These words from Chris Marker’s 1958 film-essay Letter from Siberia are echoed, later, in La Jetée, a film about “a man marked by an image from his childhood.” Both of these “images of childhood” are reprised and subtly modulated at the beginning of Sans soleil in the film’s opening “image of happiness”: three children on a road in Iceland. Between Letter and La Jetée lies Marker’s “lost period”—what one might call the childhood of his oeuvre. Maybe “childhood” is too precious a designation for what is, after all, early work, but it’s work that is more or less lost to us, orphaned from the back catalogue if not disowned by its creator. When the Cinémathèque Française presented a Marker retrospective in 1997, the director denied practicing any “retrospective self-censorship” in choosing 1962 (the year of both La Jetée and Le Joli mai) as his Year Zero. Rather, it was the case that Marker deemed this work to be merely “rudimentary” compared with later efforts. “Rudimentary” is a carefully chosen word, one that suggests “primitive” and “fundamental,” with this work representing the tyro efforts that contain all the tropes, tricks, and strategies, all the obsessions that will recur throughout the filmmaker’s career.

If the three long-form films that Marker made between 1958 and 1962—Letter from Siberia, Description of a Struggle (60) and Cuba Si (61)—have the legendary allure of “lost” works, what of the others? What of the shorts, such as Sunday in Peking (56)? What of the collaborations with Alain Resnais, such as Statues Also Die (59), which Marker and Resnais co-directed, or Toute la mémoire du monde (56) and Le Mystère de l’atelier quinze (57), to which Marker contributed commentaries? The fascination of these films doesn’t only reside in their invisibility. In them, one discovers the elements that remain central to Marker’s activities and that have always informed and run parallel to his filmmaking. It’s lately become fasionable to refer to Marker as a “multimedia artist,” particularly since he recently produced an Internet-themed feature film (Level Fivins), a CD-ROM, and a number of video installations. But this misses the fact that Marker was Multiple Media Man avant la lettre—active in publishing and as a writer and photographer prior to and throughout his film career. Letter and La Jetée are films, of course, but both also exist as books. The text of Letter was published in Commentaires 1 (61), which, with its companion volume Commentaires 2 (67), collected words and images from the films Marker had made between 1950 and 1966. Marker’s relationship with the publishing company Editions du Seuil dates back further still: to a photography-and-text collection called Coréenes (59), a critical monograph on the writer Jean Giradoux (52), a novel, Le Coeur net (The Tidy Heart, 49), as well as a long-standing and important role in designing the series of travel books “Petite Planete” in the Fifties, which, according to Guy Gauthier (the author of a recent French study on Marker’s work), “revitalized illustrated publishing in the Fifties.” Seen in the context, La Jetée was a project born not only from its director’s activities as a photographer but equally from his involvement in book design. And it, too, is also a book. Or rather, the photo-roman (as Marker described the film) became a ciné-roman in 1992, when the director produced from the still photographs and commentary text a further hybrid objet.

If Marker was seen to have innovated in his exploration of image/text relations on the printed page, this was equally true of his early filmmaking. It was André Bazin, who observed in a 1958 article, with Sunday in Peking, the filmmaker had “already profoundly transformed the customary relationship of the text to the image.” Bazin stated that Marker “brings to his films an absolutely new idea of montage, which I shall call ‘horizontal’ … Here, the image does not refer back to that which precedes it or to the one that follows, but laterally, to what is said about it.… Montage is made from the ear to the eye.” Bazin develops this formal insight into a description of Marker’s method by examining perhaps the most famous sequence in Letter. Over the same three shots of a street in which the Siberian city of Yalutsk—in which we see, consecutively, a bus, workers toiling on a road, and a local man glancing at the camera as he crosses its field of vision—runs three different commentaries. The first is a conventional Communist-era propaganda; the second, “Voice of America”-style misinformation; the third is “neutral in tone, but no more or less revealing for that. In this act of comically juxtaposing registers, Marker, according to Bazin, reveals that “impartiality is an illusion: the operation in which we participate is therefore precisely dialectical and consists of scanning the same image with three different intellectual rays and receiving back the echo.” In short, a philosophical question—“What do these images show?”—is posed with literary legerdemain. And Letter, in all its literariness, all its baggy epistolary diversity and travelogue-happy self-consciousness, is truly the model for many of the films that follow, all the way to Sans soleil, where the time-traveler (this time given a name, Sandor Krasna) writes to his anonymous female pen pal that he has “been around the world several times and now only banality still interests me.”

Sunday in Peking

Banality has a face and a name. You must make a friend of banality. In Sans soleil Marker’s surrogate-heteronym tracks it “with the relentlessness of a bounty hunter,” just as Marker himself has done throughout his career. Think of Le Joli mai and its verité vox-pops. Or the less well-known The Koumiko Mystery (65) for which Marker traveled to Tokyo ostensibly to film the 1964 Olympic Games and ended up making a portrait of a young Japanese woman, Koumiko Muraoka. Koumiko gives “banality” a face and a name and hence becomes the opposite of “exotic.” But then, perhaps “the exotic” is only the mask that banality wears, anyway.

Alert to the exotic, its lures and perils alike, Marker has invented for himself the personal of a voyager in multiple dimensions. Every continent-hopping travelogue is simultaneously a way of slicing through time; every destination is acknowledged as being already frozen in one image-repertoire or another. Take the “childhood image” of the Gates of Peking that opens Sunday in Peking, for example, over which Marker comments, “For 30 years in Paris, I’d been dreaming about Peking without knowing it” as he steps into the image from childhood and matches it against the territorial reality. It’s an image of the past set against a present that is itself in flux, and it’s often been noted that Marker’s travelogues privilege countries in moments of transformation: China under Maoism (Sunday in Peking), Siberia during a Soviet-promoted Five-Year Plan of industrialization and electrification (Letter from Siberia), Israel in its infancy (Description of a Struggle), Cuba attempting to consolidate Castro’s Revolution (Cuba Si). And while some of these films have the flavor of “Bulletins to the Brotherhood of Man” about them, engagé dispatches sent out in the spirit of international solidarity (in this respect, Marker the left-leaning Catholic humanist was very much of his generation), they also represent the development of a filmic language that would wrest the travelogue free from its taint of easeful Colonialist observation. And this is where Marker’s achievements come into their own and merit the tag of “greatness.”

Marker has explored and developed two of the most rudimentary aspects of film language: the look and the cut. “The look” is understood here as being both that of the camera itself (hence, the look of the filmmaker and, by extension, the look of the spectator) as well as “the look returned” (the reciprocal gaze of the person being filmed). It’s this look that becomes his modus operandi, his favored fetishized moment and whose motto comes in Sans soleil when, with a career’s worth of frustration behind him at cinema’s underemployment and misuse of this extraordinarily potent device, Krasna/Marker complains: “Have you ever heard of anything more stupid than what they teach at film school—not to look at the camera?” In my imagination, a young Marker-fixated video-artist is out there somewhere laboring over a found-footage opus that would be composed entirely of an assembly of all those eyes staring into the heart of Marker’s lens. In fact, Marker’s entire output is shot through with these moments that are lingered over and meditated upon. Cinema in general is described as l’imprimerie du regard (the “printing press of the look”) and Marker’s own cinema hymns “the magical function of the eye.” In this respect, he stays true to an effect of cinema’s own childhood that his alma mater, the French New Wave, actively exploited: the moment when a passerby glances into the camera’s lens and which the French film historian Jean-Pierre Jeancolas has named the “Feuillade effect” after the cinematic pioneer Louis Feuillade, whose own films, often shot on the streets of Paris, included such moments. When conventional fiction films capture these glances they come across as merely charming, naive, and unguarded reminders of primitive cinema. Marker explores them more probingly, aware that there is something magical at work here, something literally transporting in this contact between the camera eye and the human eye. The contact he seeks is less of a glance than a gaze (and even when it is only a glance, he lingers on it like a gaze) keen to establish that moment when two looks meet in a kind of equality, when the eye is, quite literally, “open.”

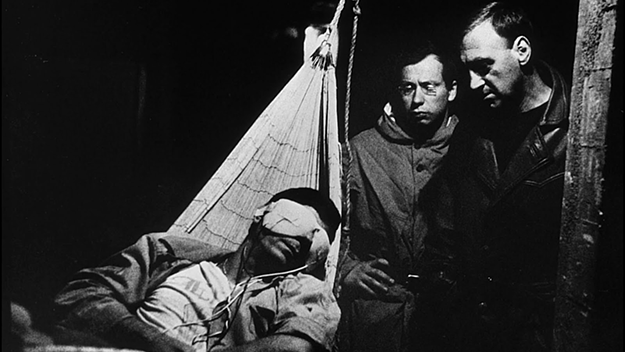

La Jetée

In La Jetée the opening eye becomes the emblem of our time. The significance of this moment in the film is emphasized by a brilliantly inventive, “rudimentary” special effect whose impact is worked up to through a refined, rhythmic panoply of cross-fades, superimpositions, and fades-to-black. A woman’s eyes open from sleep at 24 frames per second, movement animates the stills, and cinema is awoken from a photo-roman. But blink and you’ll miss it. It’s interesting to consider the way the photograph in La Jetée is associated both with death and reanimation, and to do so in the light of the first words of the commentary to If I Had Four Camels, a film made up entirely of the photographs taken in 26 countries between 1955 and 1965: “Photography is like hunting, it’s the instinct of the hunt without the desire to kill. It’s the hunt of angels.… One stalks, aims, shoots and—click! Rather than killing someone, you make them eternal.” It is into this “eternity” that the photograph delivers a landscape or a face, an eternity where time is stilled for memory to linger and reanimate it. This is what the time traveler does in La Jetée. Or, rather, it is what time has done to him and to the lost love of his memory. (Marker has spoken of La Jetée as his “remake” of Hitchcock’s Vertigo, a film about “impossible memory, insane memory.”) It is these words from La Jetée that best encapsulate the emblematic role of memory in Marker’s work: “Nothing distinguishes memories from ordinary moments. It is only later that they claim remembrance. By their scars.”

Childhood memories hit us all in the same spot, where imagination and remembering are truly indistinguishable. What gives La Jetée its force is the way it conflates childhood memory with the historical trauma of war. In a key essay on the film, Jean-Louis Schefer identifies “the memory of, or the kind of mnemonic damage, cause by war in our childhood: a primal consciousness of an era of planetary destruction which has lodged a soul within us, like a bullet or a piece of shrapnel that hit us and by chance reached a center where it could live on after having done no more than destroy a town or kill someone other than us.” Need one be reminded of how the time-traveler in La Jetée inhabited an historical context full of dread: the postwar legacy of barbarous inhumanity (wwii, the Holocaust, Hiroshima), domestic shame and strife (Algeria: torture, terrorism), and knife-edge atomic brinkmanship (the Cuban Missile Crisis). On one level, the film can be seen as having skillfully sidestepped the possible objections of the censors through its use of the science-fiction genre. After all, who was going to object to a black-and-white sci-fi photo-roman, even if its subject matter included torture and atomic devastation? Because, by the time he came to make La Jetée, censorship was no academic matter for Marker.

The heavy hand of the French state had already been brought to bear twice before, on Statues Also Die and Cuba Si. Statues, made with Alain Resnais, is a graceful but nonetheless piercing critique of colonialism in the guise of an arts documentary. “We find the picturesque where a member of the Black community sees the face of a culture” the commentary states, and the film gradually constructs an African cosmology from the “dead” statuary in museum displays of so-called primitive art. Statues remains a striking film, for the brilliance of Resnais’s camera, the polished irony of Marker’s commentary, and the supple sophistication of the ending. It is, as Marker describes it in Commentaires 1, an example of a “pamphlet-film” and its barely veiled polemical thrust was not missed by state censors who banned it for ten years before authorizing the release of a truncated version. Cuba Si, shot “at full tilt” in January 1961, was conceived, wrote Marker, “in order to oppose the monstrous wave of misinformation in the [French] press” over Castro’s revolution. The Cold War logic of the French state found its censorious alibi for refusing the film a distribution visa by invoking generic niceties; the film could not be described as a documentary because “it constituted an apology for the Castro regime.”

Sans soleil

A last word about “the cut” in Marker, the bit that strikes me as missing from Bazin’s anatomization of “lateral montage.” Marker uses his editing to traverse great stretches of time where years pass in the space of a step. Think of Sans soleil’s time-traveler who stumbles into the future as he tramps across Icelandic tundra. It strikes me that, in this understanding of the cut, Marker is close to the Soviets who, in the teens and Twenties, in cinema’s childhood, called editing “creative geography,” able to create a filmic space-time from discrete space-times. This is where Marker’s time-travelers really come into their own, an where Marker himself, “our unknown cosmonaut” as Jean Quéval christened him, endows cinema with a technical capacity that is intrinsic to it and that exceeds the simple repertoire of flashback/flashforward and in which time is understood as cinema’s true material.

Maybe we shouldn’t resent Marker’s “childhood” films being denied us. After all, obsessives are always deeply grateful for stuff that needs digging up in order to be rediscovered. But one can’t help wondering whether Marker’s example—his solitary wanderings with camera and pen, his exploration of the forms of essay, travelogue, and first-person filmmaking—is not now an example whose time has come around again. Mini dv cameras, desktop editing software, all these new technological tools are currently revitalizing first-person filmmaking. It would be a salutary realization for those exploring this form to understand that they are not the first to do so. That they are themselves children of an elusive, mercurial, quixotic father who, with a play of words for his name, with a speedy cut and the click of a shutter, has removed himself into another dimension, leaving the rest of us to make our own journeys, not so much following in his footsteps as traveling in a time machine of his design.