By Tom Paul in the November-December 2016 Issue

Art & Craft: High Fidelity

A sound designer reflects on what nonfiction sounds like

Filmmakers are not beholden to any concepts of what you can or cannot do when making a film. The medium is ours to invent and shape as we come up with new ideas. Regarding the 50 percent of the medium that is sound, as a sound designer, I have one rule: if it sounds good, it is good.

From the November-December 2016 Issue

Also in this issue

An example: a brilliant Brazilian director and friend, João Jardim, made a beautiful documentary in 2001 called Window of the Soul that he brought to me for the mix. The first scene is a close-up of a campfire. Brazilian sound designer Waldir Xavier used the sound of a babbling brook instead of fire. It was beautiful and poetic and evoked a feeling that can’t really be described. It set a slightly irreverent but, at the same time, delicious and inviting tone for the film.

Of course, when we are making something for distribution, there are standardized and very specific parameters that must be met. Beyond that, anything goes. Sound design ties the scenes of a film together, creating a cohesive environment that guides the viewer from scene to scene. When successful, it creates a space for the viewer to surrender to the film as it unfolds. Good sound in a film puts the viewer at ease, inspiring trust and confidence that the film is coming from a well-thought-out, measured place. It coaxes viewers into a receptive state for the film. Bad sound puts the viewer on edge, creates a constant apology from the film, and puts a layer of guardedness between the film and the audience. Good sound can elevate a film to the poetic and let its story shine through.

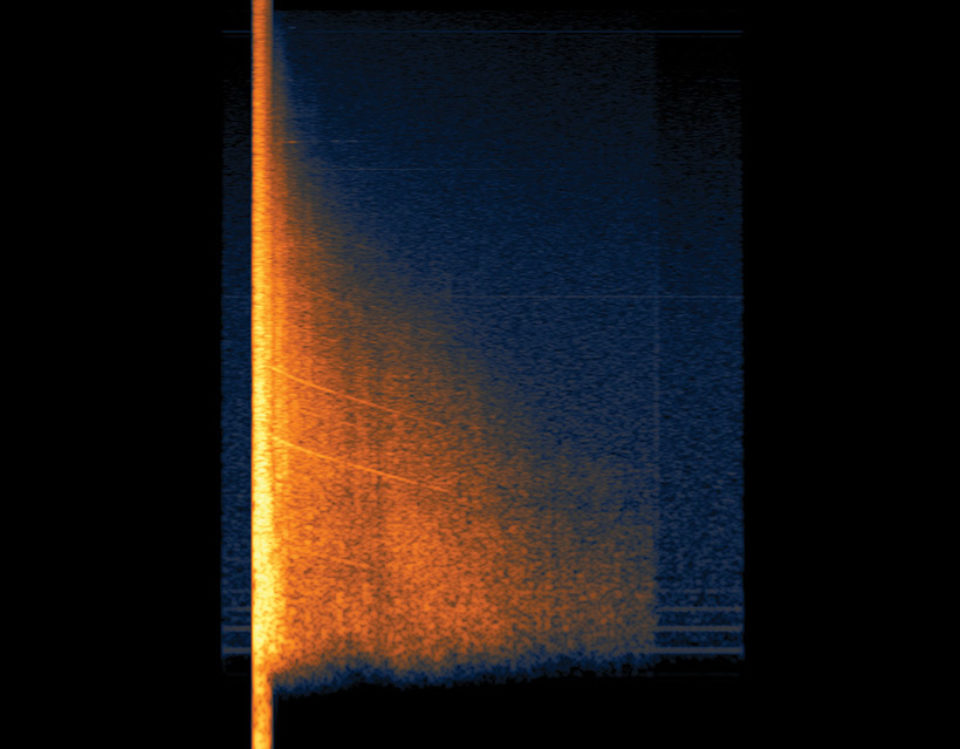

Gunshot “Crack”

But what is “good sound”? Good sound is confident sound. Deliberate sound. Delicate, detailed, and sensitive sound. It is the responsibility of the soundtrack to create a physical experience for the viewer, and to direct their attention, most often in subtle, or even subliminal, ways.

During production, there is relatively little need for creative discussion about the sound. The goal is to record it as accurately and completely as possible. In post, sound becomes more subjective, as the soundtrack is shaped around, and in support of, the narrative and the intention of the film. Both production sound and added sound, which are sometimes representational and sometimes abstract, are mixed with the score to create a soundtrack that tells a story and creates a feeling.

The audio post process starts with a spotting session. It is a full-day event, in which the director, the picture editor, the sound designer, and perhaps some of the sound editors get in a room together to conceive an approach to the film’s sound design. They go through the film shot by shot, and everything is discussed, from minute details about how to deal with problems in the production sound, to overarching concepts about how sound will function in the film. Ideas take shape. Locations are discussed. Seasons, time of day, and the type of feeling each scene should convey are all clarified.

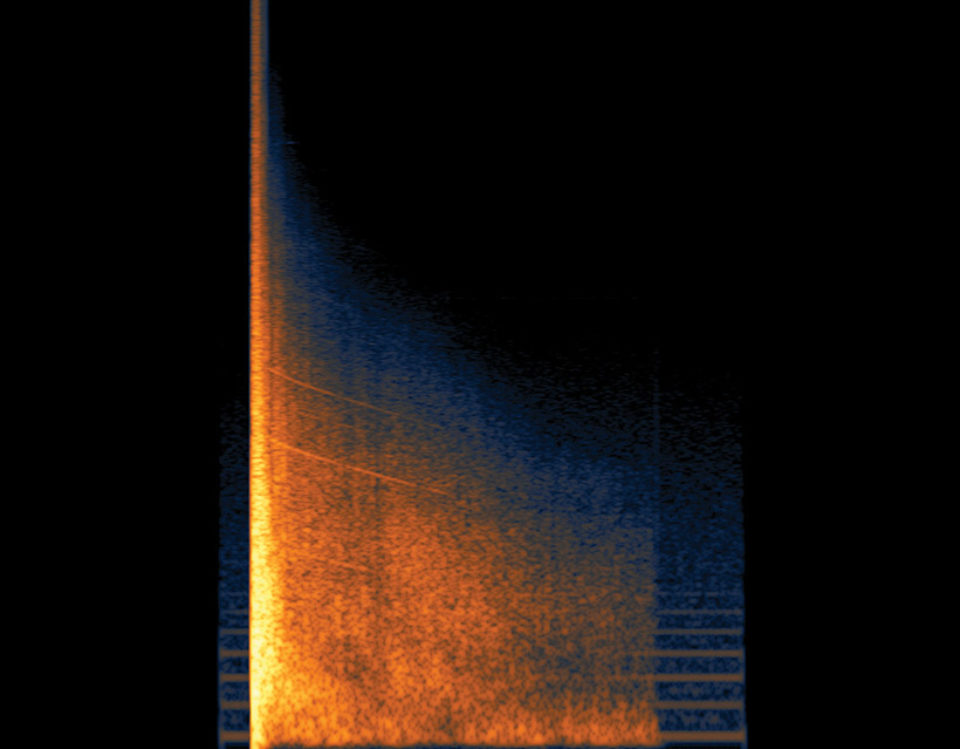

Gunshot “Meat”

After the spotting session, sound editors usually work alone, choosing sounds from the library, sculpting and layering the edit, and maybe even making embarrassing noises into a microphone, all in an effort to manifest the ideas discussed in the spotting session. When constructing the layers of sound in a scene, I am aware of the full spectrum of sound from low to high frequencies, across a range of loudness and that I am creating a complete sonic environment in which the viewer will experience the film. It feels something like interior design. We are building and decorating a sonic room for the viewer to sit in.

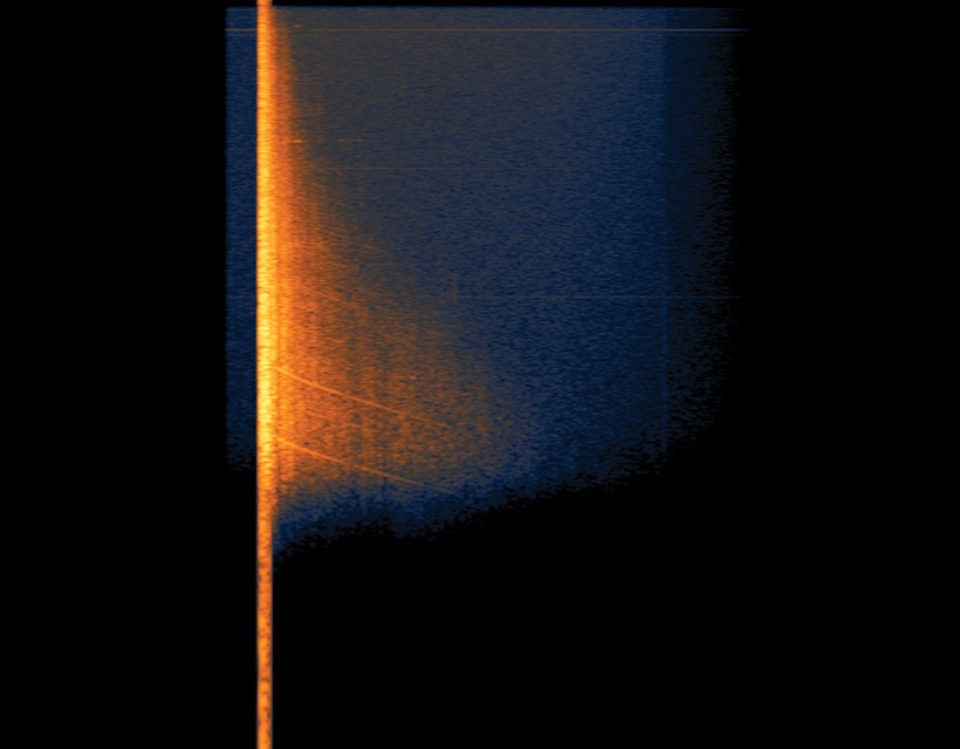

Multiple layers are often needed to create a sound. A typical edited gunshot sound may consist of three layers, sometimes up to six or more, each contributing a particular quality across a range of variables. One such variable is which portion of the frequency range each sound is best able to deliver, in order to create a balanced and complete sound, one that kicks the audience in the chest, feels substantial, and tickles the head, if that is what is wanted.

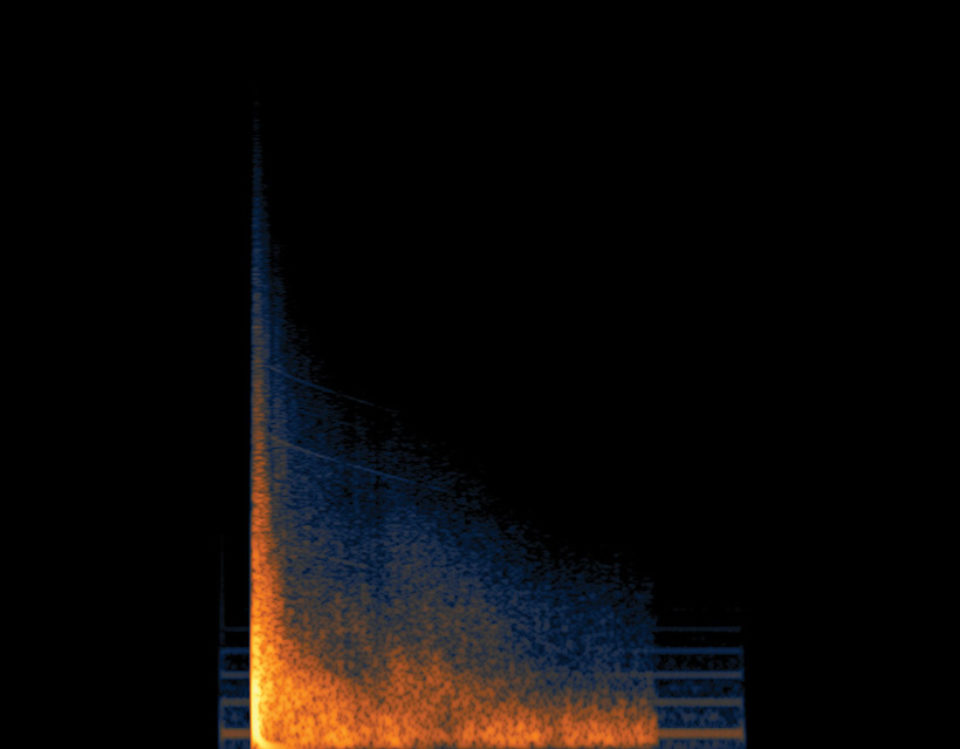

Important frequencies to include in a gunshot, for example, are “boom” (40-110 hertz); “meat” (400-1,400 hz); “crack” (2,500-10,000 hz); and “air” (15,000-20,000 hz). The edit might consist of a combination of gun recordings, each with different characteristics, as well as other non-gun sounds. A boom element may be derived from an explosion, or even a synthesizer; a crack may come from slamming two pieces of wood together, and so on. In the mix, having this separation allows a nearly infinite range of combinations and qualities to be achieved. I used this technique in Blue Caprice, based on the story of the “DC Sniper.” The gunshots were a character.

Gunshot “Air”

Sometimes the sound captured in a vérité shoot is better than anything that can be built in the studio. In Cartel Land, virtually all of the gunfire that we hear in the shootout scenes is simply production sound. Director Matt Heineman was recording in the field, often with ultra-high-quality Schoeps microphones. We had built layered sound FX, but in the mix, though they sounded inarguably “good,” we decided not to use them, as the actual vérité recordings packed a more emotional punch.

Occasionally, a director actually forbids the use of Foley and library sounds and mandates that we use only sounds that come from the production recordings. Zana Briski, one of the directors of Born Into Brothels, worked this way. Fortunately for us, and for the film, she was a passionate wild-sound recordist and she provided a rich collection of sounds from Calcutta that she herself had recorded.

Every sound designer has a personal library that grows and evolves over the years. I started out as a location sound recordist, traveling all over the world recording sound for documentary and narrative films. I have thousands of original recordings from those days. Each film project brings new additions to the library as well. Particle Fever, about the Large Hadron Collider and the discovery of the Higgs boson, required the creation of very abstract sound design and yielded a collection of new and unique sounds. I often mine the production tracks of a film for new sound effects. The location recordings for Sand Hogs, about miners who dig tunnels, contained a lot of very special sounds of enormous underground drills, explosives and other processes involved in the work.

Gunshot “Boom”

A relationship grows over the years between a sound designer and his or her library, with some sounds becoming “go to” favorites. We may see something on screen in the spotting session and know instantly which sound, among the hundreds of thousands in the library, is the right one to choose. A sound is chosen based on criterias of sync, accuracy, recording quality, and, quite significantly, mood. For example, if a director tells me that a scene should feel somber, I will have that criteria in my head as I look for a sound, such as a car driving by. I may audition five or 50 sounds, or however many it takes, until I find one that feels something like “somber.” Or maybe I find one that almost works, and I modify it. I may alter the pitch, the speed, the EQ (equalization), or treat it with anything from a mild to an extreme effect to make it feel right. Often a combination of sounds, especially sounds that have some tonal or pitch element to them, can be combined, according to the conventions of musical harmonic structure, creating an emotionally evocative effect, almost like a musical score.

Occasionally, at a Q&A after a screening, someone will ask a protesting question about adding “extra sounds” to a documentary, and what that means to the film’s journalistic integrity. I think that we need to let go of the concept that a documentary is, or can possibly be, objective. In the editing room, the act of choosing one shot over another, following one story line at the expense of another, or choosing to include one response from an interview instead of another, all make the filmmaker’s subjective viewpoint inescapable.

So, successful filmmaking becomes about trust. A successful film—and a successful sound design—inspires the viewer to trust it, and the filmmakers, to tell them the most important and relevant bits of the particular story they are experiencing, with healthy discrimination and integrity. The environment created by the sound design literally defines the world in which the viewer experiences the film. For me, as a sound designer, it is a great honor to have that responsibility.

Tom Paul is a two-time Emmy Award–winning sound designer who has worked on over 200 films including Weiner, The Square, and The Fog of War. He is a partner at Gigantic Post in New York.