Unstable Objects: FIDMarseille 2022

This article appeared in the July 26, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

A Woman Escapes (Sofia Bohdanowicz, Burak Çevik, and Blake Williams, 2022)

“The following is a story that is somewhat true” reads the handwritten title card that opens A Woman Escapes, one of the standout features at this year’s FIDMarseille. The line might be used to describe much of the slate at this year’s edition, which was a showcase for essay films, mid-length hybrid documentaries, and experiments in autofiction. The festival was inaugurated in 1989 as the International Documentary Festival of Marseille before changing its name in 2011 to the International Film Festival of Marseille—but doc-heads needn’t panic: with an international jury presided over by French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop, whose own practice straddles documentary and fiction, this year’s festival was full of films that played with notions of documentary form, authenticity, and duration. It makes sense that the top prize was awarded to Daniel Eisenberg’s The Unstable Object II, a boundary-pushing three-and-a-half-hour observational doc that doubles as an art installation, and which looks at different modes of production in factories across Germany, France, and Turkey.

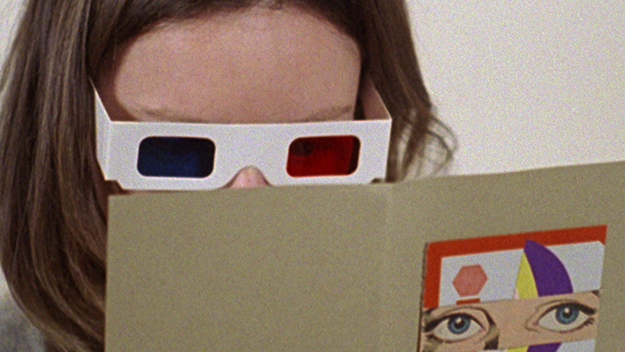

Co-directed by Sofia Bohdanowicz, Burak Çevik, and Blake Williams, A Woman Escapes is a collaborative work of autofiction—and possibly the world’s first 3D breakup movie. Fittingly, I watched it in the futuristic Cinéma Artplexe, a newly built multiplex that looks like a spaceship crash-landed on Marseille’s historic La Canebière. The film follows the newly heartbroken filmmaker Audrey Benac (Deragh Campbell) in Paris as her friends Burak and Blake attempt to lift her out of an emotional and creative funk through a series of video letters. Çevik and Williams shoot and narrate their own letters, while Bohdanowicz films Audrey in fuzzy-edged 16mm as the character wanders the apartment that belonged to her late friend, an astrologer named Juliane. Audrey is a kind of avatar for Bohdanowicz—she appears in four of the director’s other films, essayed each time by Campbell. (The character of Juliane is drawn from Bohdanowicz’s life, too—she was a real-life friend and collaborator who passed away shortly before the pandemic.)

Weak from grief, Audrey struggles to tend the rose boxes that line Juliane’s balcony, barely able to lift a metal watering can. So Blake mails her a small 3D camera, and encourages her to try a new perspective. His correspondence is rendered in stereoscope: he browses her neighborhood in Montmartre on Google Street View to feel close to her, the image glitching and warping when he zooms in too deep. He sends her a video letter about his professor mourning the video artist Nam June Paik, with Paik’s 1964 Zen for Film—in which light passes through a blank strip of film stock, exposing the marks and imperfections that accumulate each time it is played—becoming a visual metaphor for all the ways in which Audrey does move forward, even as she feels stuck in the mud of depression. Burak’s missives, shot in crisp digital 4K, betray a cheeky sense of humor: he sends her a video of a despondent dog that, like her, is unable to articulate its feelings. Throughout the film, hope appears in tactile stereoscopic images like roses that unexpectedly climb out of the screen, a cheerful beagle, and a billowing sheet of sheer organza. In a film about loss, these haptic moments feel like bursts of optimism.

Narimane Mari’s We had the day bonsoir—a tribute to her late partner, the painter Michel Haas—was also sparked by grief. To call the film an elegy, however, would be to mischaracterize its vibrancy. Sanguine from the outset, the film collages documentary snippets of Haas that teem with life. He wheezes with laughter while watching Charlie Chaplin fall about a boxing ring in City Lights; sings lustily to himself in his studio, feet filthy with paint; and bounds across a dry and rocky landscape as Mari drives alongside him. Mari insists on her lover’s dignity, her camera fixed on the artworks on the wall as the doctor tells Haas that palliative care is the next logical step for him. He shuffles in his sheets, his resistance audible. She turns her lens on a hanging basket in their apartment, green shoots sprouting beneath the plant’s decaying brown leaves. “Look, it grows back,” reads the subtitle that appears on screen. This defiant and joyful hour-long film deservedly won the top prize in the festival’s French Competition as well as the National Centre for Visual Arts award, which celebrates experimental filmmaking.

One of the most transfixing films I saw at FIDMarseille was tucked away in the festival’s “Other Gems” strand, which hosts world premieres and new restorations screening out of competition. Fall is the eighth feature from the prolific 23-year-old Russian filmmaker Vadim Kostrov, and like his previous “seasonal” films Summer and Winter, it takes place in his hometown, the industrial city of Nizhny Tagil. For 99 minutes, Kostrov’s mini-DV camera follows a latchkey kid in a yellow baseball cap — a version of Kostrov as a child, played by Vova Karetin, who also appeared in Summer — as he wanders the city and its suburbs alone.

“I hope the film puts you into a calm place,” the director said in his introduction—and indeed there is a soothing, ASMR quality to his slow cinema, with its textured, lo-fi long shots and ambient soundscape comprising the rustle of trees, the whir of cars, the happy chatter of children playing in the park. There is little drama, no dialogue, and a strange lack of human faces to lock into. Sometimes, Kostrov adopts the child’s point of view, but he never allows the viewer to get a good look at Karetin’s own face. Yet the longer I spent with this little boy, the more I started to notice his stride—purposeful but languorous, as though he were trying to slow down and eke out a little more time. In one lengthy sequence, he sits on a rock, dwarfed by a surrounding forest and looking out over the city as though perched on his very own Hollywood sign, the star of his own life. The 10 people who walked out of my screening, presumably fed up with waiting for something to happen, missed out on the film’s subtle, slow-building revelations.

Mini-DV is put to similarly atmospheric use in Lluís Galter’s Aftersun, a freaky mystery set in a holiday camp in Costa Brava and shot like a home movie. Three sisters sit poolside, rapt, as an older man tells them about a boy who disappeared at the very same camp 20 years ago. A man in a bear suit is staying in a camper nearby, a situation both funny and oddly threatening. Nothing bad happens, exactly, but there is the sense that innocence just might be at risk. Galter’s ironic use of Debussy’s twinkly, fairy-tale-esque “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun” underscores the dodginess hovering just outside the frame, as the girls spend the rest of the movie playing cards, sunbathing on the beach, and wandering through tall grass without their parents. In an interview, Galter explained that while a Swiss boy named René Henzig really did disappear in Sant Pere Pescador (where the film is set), his story and its protagonists are entirely invented. I was both impressed and unnerved by how specific both felt, as though they had been dredged up from a dream.

Simran Hans is a writer and film critic living in London.