Try to Imitate Others and Fail: An Afternoon with Bresson

This article appeared in the January 5, 2024 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

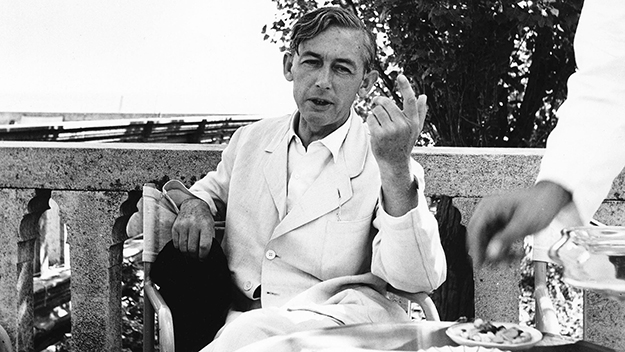

Robert Bresson in 1955

In 1979, at the end of my first year at NYU’s graduate film school, my faculty adviser suggested that Paris was the place for me to pursue my filmmaking dreams. She told me she had friends there who could help me out, and within weeks my apartment was sublet and I was on my way to France. I wasn’t sure if it was filmmaking or criticism I’d pursue once there, but both plans were equally unrealizable, since I had neither work papers nor any knowledge of French. I did, though, have something else driving me: the desire to meet some of the filmmakers I loved, above all Robert Bresson.

Shortly after arriving in Paris and settling into a chambre de bonne, I looked in a phone book, and there I found Bresson’s address. I wrote to him asking if I perhaps could meet with him. A few days later I received an envelope postmarked June 19, 1979, and addressed in an old man’s handwriting. The letter it contained read, in French:

Dear Sir: Thank you for your kind letter. I would be very happy to see you. Can you please call me in the morning or at lunchtime so that we can converse about a meeting.

Yours,

Robert Bresson

I called as requested, and a few days later I was seated facing Bresson in his living room on Quai Bourbon, on the Île Saint-Louis. In my memory, the principal source of light was Bresson’s shock of white hair.

When our meeting was done, I hurried home and carefully transcribed the contents of our conversation, which lasted a couple of hours. A few months after returning to the U.S., wanting to convert the notes into an article, I discovered that the notebook in which I’d transcribed Bresson’s words had disappeared. It remained lost for over 40 years. Recently, while going through a box filled with personal documents and left-wing newspapers and magazines from my youth, I found it. What follows is a report of our chat. Most of it was in English, though Bresson occasionally slipped into French. In the few weeks I’d been in France, I’d begun to pick up some of the language, so when he did revert to French, I was able to follow him.

***

As he does in his book, Notes on the Cinematograph (1975), Bresson stressed to me the importance of the ear—how much more it suggests than the eye, and how images should be replaced, when possible, by sounds. He told me a story that an ophthalmologist friend had told him, about a man who was blind from birth and who, when he regained his sight, wanted to be blind again. He was touched to hear that his book had impressed students in film school, and said he wanted to write a longer one but that he doesn’t have the time. He wanted to know about the quality of the translation, which I praised.1

He never goes to the movies, though he did see Straub and Huillet’s Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach (1968). He found it ugly and empty, and thought the music was badly played. I had read that Straub had worked as his assistant director, but Bresson denied that this had ever been the case, though Straub did come to see him from time to time. One of the reasons Bresson doesn’t go to see films is that he can’t stand the way they sound. He hates filmed theater and can’t sit through it. The minute you use a professional actor, you involve another medium, not just cinema. He can’t watch films in a foreign language (with subtitles, he says), because each word, each sound is important, and the subtitles take that away. Bresson doesn’t go to see his own films in theaters, because often when they’re projected, lines of dialogue are missing, which changes the film completely for him. He is in the process of trying to purchase all the prints of all of his films.

He shot his first film, Affaires publiques (1934), at a time when he was still going to the movies and seeing a film a day. No one gave him any advice, and he had no training; he just went out and made the film. He doesn’t count it as part of his oeuvre.2 He hadn’t met the actors in his first feature, Les Anges du péché (1943), before he began shooting, and even then he went about making films differently. He told the producer that either he would make the film his way or it wouldn’t get made at all. In making Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne (1945), he wanted to keep the spirit of Denis Diderot’s dialogue, which he loved, but even so he had problems writing the men’s dialogue. Jean Cocteau did it for him in 10 minutes. As a result, Bresson doesn’t find it to be a unified film, since parts of it are his work and parts are Cocteau’s. Diary of a Country Priest (1951) was a film made for hire, a project that he at first turned down. Upon reflection, he realized that it was an honor to make a film that would be so important.

Bresson stressed the role of memory—of personal memories—in his films. In Diary of a Country Priest, for example, he tried to recreate the light that fell on his childhood home, and the way he remembered people entering rooms. In Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), he was partly inspired by a young woman he saw standing on the riverside near one of the bridges over the Seine. She, like Marthe in the film, had for some reason removed her shoes. He was also inspired by the beauty of the bateaux mouches (tour boats) that go past his windows and the life on the Pont Neuf bridge, which he loves tremendously and where he loves to stroll. He had many problems while making the film, since the producer walked off with half the budget, causing him enormous difficulty in finding funds for the remainder of production. Four Nights was, Bresson said, the only one of his films that the critics didn’t like, and it was withdrawn after just two days from the theater at which it was showing on the Champs-Élysées. The film, he asserted, was given no publicity.

He casts his films by picking just anybody for a test. Then, after speaking to them on the phone, he decides if it’s worth seeing them in person (he can tell everything about a person, even the way they look, over the phone), and then tests as many as 60 people for a role. He applies a similar technique when he’s contacted by cinephiles. He never sees anyone who calls him directly, but instead invites those who write to him to call. When they do, Bresson can tell if it would be worth seeing them. As a result, he sees very few people.

He always uses postsynchronized sound. His films are often shot outdoors, and the recorded sound is unusable. Then he cuts the film into snippets of a sentence or two each, and, without projecting the film, gives an actor a line reading. They do as many takes as are necessary, and when he finally has what he wants, he projects the scene, and its sound and image are synced up. When he was shooting in black and white, he used to do 20 takes until he got something that was right. But color is too expensive for this process, so now he only does two or three takes, though many more takes are done of the line readings.

There were no projects he was unable to make, though it took 20 years for Lancelot du Lac (1974) to reach the screen. He is now working on a film about money, which will be shot in a year.3 He has prepared a film of the Book of Genesis from the creation until the Tower of Babel, which, he says, he will film in his own way. Bresson feels that short, inexpensive films are the only way to go for young directors, since they leave them free to control the finished work totally. He told me not to search for originality: “The thing to do is to try to imitate others and to fail.”

Formerly a painter, he doesn’t own a single one of his canvases (he was proud to say). He sold most of them to a German collector named Levy before the war, and doesn’t know what became of them. His mother lost the rest in the course of her moves. There’s not a single day in which he doesn’t want to paint, but he hasn’t the time or energy to both make films and paint. When he gives up making films (which will be soon), he intends to paint—nature, “of course.” He isn’t interested in abstract, intellectual painting. Rather, he wants to communicate his impressions, an intention that carries over to his films.

In editing, he stressed the importance of the shock created by the meeting of two images. He writes very detailed scripts, which he then puts in a drawer. He tries to discover something new when he gets to the set. He loves the cinema and thinks it is a great means of expression, but he is struck by the fact that so many of the people who come to see him view it simply as a way of making a living.

He hates much modern poetry because it strains after originality. He finds it “nul, vide” (useless, empty). Bresson didn’t know Pierre Klossowski’s writings when he used him as an actor in Au hasard Balthazar (1966). He doesn’t read any contemporary writers, and has never been much of a reader. He begins each day with two or three pages of a classic (Montaigne, Proust, Valéry, Pascal), which brings him joy and makes him able to face the day. He only works in the morning, and is finished once he’s eaten lunch. When I asked him how he can put down intellectual art when he’s adapted Dostoevsky and Georges Bernanos, he said, “Yes, but I did them in a very personal way.” He said that when he read Bernaros’s Mouchette he didn’t like the ending, but that as soon as he read it he knew he was going to film it. He knew of Godard’s intention to make a film of it, and said that Godard was going to do all kinds of crazy things with the book.

***

Bresson invited me to call again, but I didn’t for over a year. We spoke on the phone a few times, and he again told me to call when I was next in Paris so we could discuss my working on his next film. I called him in 1983, and he apologized and said that his crew for L’Argent was “archipleine”—totally full. This proved to be his final work.

Endnotes:

1. In fact, the translation, which I’ve since learned Bresson and his wife were very attached to, contains a mistake that falsifies the entire book. The edition then available, published by Urizen, bore the title Notes on Cinematography, and throughout the book the word “cinematography” is used to describe the cinema Bresson aims for. In fact, the correct translation is “cinematograph,” the translation now used by NYRB Classics for the title of its edition of the book. Unfortunately, every English-language version, including that of NYRB Classics, has maintained the incorrect word in the body of the text.

2. At the time I met Bresson, the film was thought lost. A print of Bresson’s sole attempt at slapstick was found in 1987 at the Cinémathèque Française.

3. Bresson seemed to be referring to L’Argent, which he didn’t make until 1983.

Mitchell Abidor is a historian and translator who has published over a dozen books. He is currently working on a biography of Victor Serge.