Present Tense: Tomboys

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

Tatum O’Neal in The Bad News Bears (Michael Ritchie, 1976)

“Laced with larceny…loaded with laughter! For 10% of the action, and a red Ferrari, she’d con her own grandmother.”

That’s the tagline on the poster for Disney’s 1977 film Candleshoe, starring Jodie Foster, David Niven and Helen Hayes. Foster appears on the poster as a towering figure in blue jeans and a T-shirt, cocky grin on her face. She was 15 years old at the time, and in the unique position of being a Disney child star and also an Oscar-nominated actress (for her performance in Scorsese’s Taxi Driver the year before). Candleshoe’s gleeful tagline could be chalked up to the 1970s-era vibe of malaise and cynicism filtering down into even G-rated movies. But Candleshoe is an example of another trend, a trend looked back upon fondly by those of us who were kids at the time: the trend of the tomboy.

Movies like Paper Moon, The Bad News Bears, Freaky Friday, Candleshoe, and 1980’s Times Square are the most well-remembered “tomboy films” of the era, with Jodie Foster and Tatum O’Neal as tomboy patron saints. Days of Heaven and Out of the Blue established Linda Manz’s tomboy bona fides. Little Darlings (1980) is another interesting entry, with Tomboy Goddess O’Neal, now older, segueing into playing the snooty rich girl, with a tough-talking chain-smoking Kristy McNichol in the “tomboy” role. Perhaps you’d have to have been a little kid at the time—and a little girl, in particular—to get how revelatory these figures were. I didn’t intellectualize why these movies spoke to me. I loved books about tomboys, too, like Harriet the Spy, or Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird, Jo March in Little Women, Frankie in Carson McCullers’ The Member of the Wedding. These characters were unbothered by convention and therefore aspirational. I was the only girl on my Little League team. I lived out my own Bad News Bears fantasy in real life. I had crushes on boys, but I loved even more so being pals with boys, and not being silly (as I saw it) about boys. I didn’t understand why Jo and Laurie in Little Women couldn’t just segue into an adult romance. Was something not transferable? These vague feelings, not really articulated, found expression and catharsis in watching all the great tomboy films.

But beyond that: the tomboy characters were fantastic and exciting! They were scrappy street urchins. They talked like gangsters. Sometimes they were actual criminals. They smoked cigarettes. They sassed authority figures, and when told to knock it off, they sassed even more. They flipped the world the bird. They were the smartest person in any room, even though they were between the ages of 9 and 14, and even though they were girls. Theirs was an ongoing act of civil disobedience against the limits imposed on girls, the idea that girls should behave one way, boys another. The 1970s tomboy refused to even recognize such a stupid system, stacked as it was against girls (even more so once their bodies started to develop, a reality they all seemed aware of in a hazy way).

Christopher Connelly and Jodie Foster in the television series Paper Moon (1974)

The “tomboy archetype” was not born in the 1970s, of course. She’s been around for centuries. When Shakespeare had his heroines dress up as boys, swashbuckling their way through a gender-bending forest, he knew what he was doing. Jo March in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women is the apotheosis of all things Tomboy, declaring disconsolately in the first pages of the book: “I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy, and it’s worse than ever now, for I’m dying to go and fight with papa, and I can only stay at home and knit like a poky old woman.” Tomboys fulfill a very powerful need, but they have transformed with the times, reflecting the concerns of any given era. Michelle Ann Abate’s fascinating study, Tomboy: A Literary and Cultural History, tracks the tomboy through American culture, showing how she has taken on different forms, with chapter titles showing her transformations: “The Tomboy Is Reinvented as the Exercise Enthusiast” or “The Tomboy Shifts from Feminist to Flapper.” Tomboys pop up through the timeline of literature, art, movies, before being submerged (or drowned, more like it) in the mainstream’s reassertion of traditional gender roles.

One of the unique aspects of the 1970s tomboy is how the formerly subversive went mainstream. Tomboyishness was the dominant model for little-girlhood for a brief glorious season. Promoted by Disney, no less! “Tomboy” as a term is not really in use anymore, and is now looped into things like gender fluidity and non-binary identities (Céline Sciamma’s first three films—Water Lilies, Tomboy, and Girlhood—examine gender identity at different stages of a girl’s life: childhood, pre-adolescence, and adolescence.) As long as the culture insists on telling girls whom they should aspire to be, tomboys—or whatever you want to call them—will be necessary.

The ’70s tomboy stands out because she was “laced with larceny.” She was not a particularly good kid. She was an outlaw. In Peter Bogdanovich’s Paper Moon, Tatum O’Neal’s Addie Pray is a sophisticated grifter. She’s a child anti-hero. The opening shots of Candleshoe (directed by Norman Tokar) introduce Casey (Foster) as the head of a gang of boys, playing Frisbee with a stolen hubcap, breaking up the basketball game of a rival gang, and eventually fleeing from the cops. Casey has been shuffled around the foster care system, taken in by people who want the welfare check. Casey is practically feral, with no sentimentality about her situation. When someone refers, in mournful tones, to her “deprived childhood,” she snaps, “I ain’t deprived. I’m delinquent. There’s a difference.” A hustler named Bundage (Leo McKern) comes to her with a proposition: a rich lady in England (Hayes) lives in a manor called Candleshoe, and Bundage has a tip that somewhere in Candleshoe is a treasure trove of Spanish doubloons. He needs Casey to claim to be the lady’s long-lost granddaughter, so she can infiltrate the house and find the treasure. Casey’s first question after she hears his pitch: “What’s in it for me?” She drives a hard bargain. Once inside Candleshoe, she befriends the butler Priory (Niven), and discovers that Lady St. Edmond is not rich at all: she is about to lose Candleshoe because of high taxes. On top of that, Lady St. Edmond has taken in a group of stray children, but Casey wants no part of the happy “found family” of Candleshoe. She just wants her cut of the action. She begins her secret quest to find the doubloons, declaring at one point, “The whole world’s a racket.”

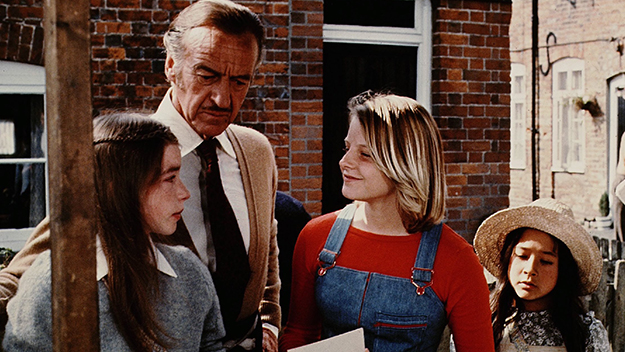

Candleshoe (Norman Tokar, 1977)

Little girls are often called upon to be inspirational, they are used symbolically, to touch our heart-strings. Casey is anti-inspirational. In the final scene she sheds a tear, and says, “That’s the first time I cried.” You believe her. Candleshoe is a romp, featuring a cast of eccentrics, with both Niven and Hayes giving very funny performances. But at the center of it is a swaggering 15-year-old girl, tough as nails, doing what she has to do to survive. Even more refreshing, Casey’s tomboyish-ness is not treated as a problem to be solved. There isn’t a scene, for example, where she puts on a dress and everyone gawks at how pretty she is. There isn’t a scene where we in the audience are “reassured” that Casey may be a tomboy but she isn’t a lesbian (a common moment in many tomboy tales, where any potential queer reading of the character is stifled). In Candleshoe, Casey is gloriously herself, to the end.

What happens to the tomboy after adolescence? The example of Jo March is not exactly encouraging. I have often wondered if the tomboy grew up to be a “Howard Hawks Woman,” those wisecracking dames freely operating in a man’s world, embodied by characters like Lauren Bacall in To Have and Have Not or Rosalind Russell in His Girl Friday. Jean Arthur in Only Angels Have Wings is an interesting case. You could look at that performance and say: “This is the story of a character in a Howard Hawks film trying to be a ‘Howard Hawks woman,’ and finding it very difficult.”

A wonderful addition to the tomboy movie library, and a film that looks at the question “What happens after adolescence?” in thought-provoking ways, is Gina Prince-Bythewood’s Love & Basketball, starring Sanaa Lathan and Omar Epps, as childhood friends who segue into a romance, bonded together through basketball. Monica’s mother (Alfre Woodard) pressures her to start acting like a lady, start caring about makeup and boys. At one point, her mother says, “I don’t know why I keep hoping you’ll grow out of this tomboy thing,” and Monica snaps, “I won’t. I’m a lesbian.” (Beautifully, this mother-daughter tension remains somewhat unresolved at the end.) Monica has a crush on her best friend Quincy (Epps), who lives next door. The two of them bonded as children over basketball and they still blow off steam playing one-on-one. But Quincy is a ladies’ man, and Monica doesn’t know how to compete.

Monica has internalized the world’s assessment of her: she’s a jock, therefore she’s not really a girl. Lathan bravely shows how easily Monica is hurt by rejection, how badly she behaves when threatened, how lonely she is. (Lathan understands loneliness on a profound level. In Something New, loneliness vibrates around her like a migraine aura.) Prince-Bythewood does not betray her tomboy lead character. Monica does have to change, although “change” does not mean acting more like a lady so her man will love her. Monica’s change is more challenging than that.

Kristen Stewart in Personal Shopper (Olivier Assayas, 2016)

The tomboy continues to transform herself in pop culture. Personal Shopper is not exactly a tomboy movie, but Kristen Stewart’s performance exists in such a fluid space it feels relevant: She’s boy-girl, femme-butch, neither/nor, simultaneously. The interest in Little Women is ongoing, because the book has been adapted to film so many times (Greta Gerwig’s the latest in a long line), and so the different versions reveal how the wider culture views Jo March’s tomboyish-ness, how much tomboyish-ness “we” can take. (Farran Smith Nehme’s 2016 essay about the film adaptations of Little Women is essential reading.)

Tomboys for me as a child did not represent not wanting to be a girl. It was about being free of the idea that girls liked dolls more than baseball, that girls are naturally sweet and sedate. You can’t be sedate when you’re sliding into third base. Tomboys are self-reliant. They demand 10 percent. Or, like Addie Pray, they demand $200. Sweet talk doesn’t work on them. They refuse self-pity. They’ll work it out for themselves.

In her poem “Often Rebuked,” Emily Bronte (called “stronger than a man” by her sister Charlotte), declares:

I’ll walk where my own nature would be leading:

It vexes me to choose another guide.

It is the anthem of the eccentric. It is the cultural outlaw’s declaration of independence from unwanted fetters, unasked-for assumptions. In a world in which girls are expected to mold themselves to other people’s expectations, the most powerful thing a girl can do is ask, like Casey in Candleshoe: “What’s in it for me, huh? What’s in it for me?”

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.