Present Tense: Nick Nolte

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

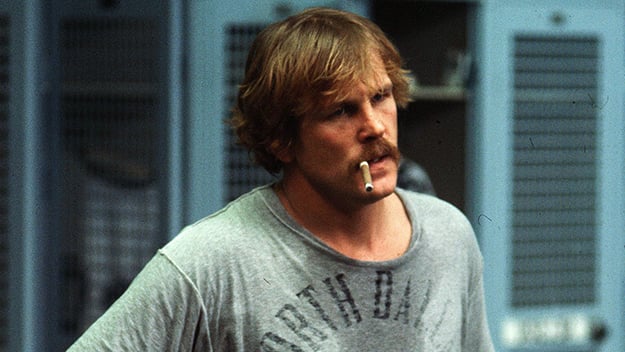

North Dallas Forty (Ted Kotcheff, 1979)

There is nothing comforting about Nick Nolte’s screen presence. He has often played men tormented by regrets, by pain so deep it can’t be acknowledged, by self-loathing. Nolte’s characters are often weighed down by the most horrible kind of self-knowledge. They are men who can’t just casually glance at themselves in the mirror to straighten their tie; no, for them, one glance and they are instantly unmasked. At times, Nolte almost twitches with comfortlessness, or, maybe more accurately, invests his energy in trying to hide his comfortlessness through bluster, rage, addiction, or a blinding humorous charm. Nick Nolte is a complicated man, and has lived a chaotic and rebellious life (his 2018 memoir was perfectly titled: Rebel: My Life Outside the Lines). In a 2016 interview with Indiewire, he spoke of Graves, his television series about a former American President who realizes after leaving office he has done more harm than good, and sets about to make amends. Nolte said, “[The character is] 75, I know he’s fucked up enough, no matter what he does, to have regrets. Things you would like to fix, things you would like to correct, they’re buried deep in all of us.”

Regret may seem like an old man’s game, but it’s really not. At any rate, Nolte came to it early. Nolte was old young. Gifted in sports, he played on the football team in high school, while simultaneously developing enough of a drinking problem to be kicked off the team. He went to a series of colleges, where he played football, baseball and basketball, but didn’t graduate due to poor grades. He was interested in acting by then. While he did study the craft, Nolte learned mostly by doing, appearing in regional theater productions all over the country. When he was busted in 1966 selling counterfeit draft cards, his career could have ended before it even began. He was given a heavy prison sentence (subsequently suspended) and the brou-haha meant he wasn’t allowed to serve in the Vietnam War, which, ironically, he had wanted to do. He frequently mentions his regret at not having served. Regret, again. It is a theme. He got intermittent work in television through the late 1960s and early 1970s, but it was slow going. The break came when he appeared in the 1976 mini-series adaptation of Irwin Shaw’s novel, Rich Man, Poor Man, where he was perfectly cast as the rebellious Tom Jordache. There’s something to be said for getting your big break when you’re 35, as opposed to 25. Both scenarios have their upsides, but Nolte “arrived” with miles of bumpy road behind him, as well as years of real-life experience and experience as an actor. He was ready.

In North Dallas Forty, the 1979 film based on Peter Gent’s brutally honest novel about professional football players, Nolte plays Phillip Elliott, a busted-up wide receiver with the North Dallas Bulls, creaky with injuries, and self-medicating constantly, popping pills, bed-hopping, drinking, and chain-smoking (while lifting weights). Phillip is a young man, relatively, but he is already a spectacle of near-total ruination. Everything in his body hurts. There’s a scene early on, at a wild party, where he is left alone at a table, and all of a sudden, his social self vanishes, and the bottom drops out in his eyes. And then, another bottom drops out. He empties out, and sits there, almost slack-jawed, far away inside himself. This is Nolte at his very best. His vulnerability has always been in stark contrast to his lumbering bulk.

Graves, Season 2, Episode 202: “In His Labyrinth”

There are other such moments in his career, moments where a character—invested in his social persona—drops it, and a chasm opens up. The aforementioned television series Graves starts with a closeup of Nolte staring at himself in the mirror. His face looks ravaged, like his insides are on the outside, and his eyes gleam out of the wreckage with icy-blue intensity. This is a man who has done much harm, and he is no longer able to live with himself. There’s the terrifying moment in Affliction (1997) where he stands in the middle of the street, arms flung out on both sides, his head flopped down on one of his shoulders. Cars beep at him. He stands so still it almost seems like it’s a freeze-frame, giving the moment a Gothic aspect. He’s a gargoyle, frozen in some grimace of unnameable horror.

Nolte is practiced at playing men who, on some level, refuse to know themselves. If you play an uncommunicative character, or an un-self-aware character, you don’t want to “cheat” and make the character more expressive or vulnerable than they would actually be. You have to be truthful. And Nolte is truthful. When playing a man who does not know himself, the prison he is in is airtight. This can manifest itself in sinister ways, as in his performance as corrupt racist cop Mike Brennan in Sidney Lumet’s Q and A. But then in Barbra Streisand’s Prince of Tides, his Tom Wingo (for which he was his nominated for an Oscar) cannot afford self-awareness, because if he took a second to reflect, all he would see was the trauma he endured as a child. Tom has set up his whole life—his whole personality—so that he never has to look at what happened to him. His already huge charm is in high gear in Prince of Tides, but it’s a tragic charm, because it refuses to admit loss and powerlessness. The scene where he finally breaks down into sobs is a masterpiece, mainly because Nolte is playing the character’s resistance to breaking down as strongly as he plays the breakdown itself.

Nolte takes risks. In Scorsese’s remake of Cape Fear, Nolte—so powerful physically—is completely believable as an emasculated man, in a hothouse-marriage made up of recriminations and blame. Lorenzo’s Oil is much better than it is given credit for, and Nolte—with thick Italian accent—plays a man who doggedly refuses to accept that “nothing can be done” for his sick son. In one scene, he is given the worst possible diagnosis, and Nolte is shown sliding down the stairs on his back, head bumping against each step, mouth open in an Edvard Munch-type scream, hand clutching his heart. It’s an astonishing bit of physical and emotional acting. His work is an example and a challenge to others. This is how deep it is possible to go.

Rosanna Arquette and Nick Nolte in New York Stories (Martin Scorsese/Francis Ford Coppola/Woody Allen, 1989)

One of his best performances is as the painter Lionel Dobie, in “Life Lessons,” Martin Scorsese’s “chapter” in the trilogy New York Stories. Dobie is a wreck of a man, living and working in a warehouse space, obsessed with his young assistant Paulette (Rosanna Arquette). It’s an excruciating portrayal of romantic and sexual obsession, up there with Travis Bickle’s neurotic fixations in Taxi Driver and Art Garfunkel’s tremendously unhinged behavior towards Theresa Russell in Nicolas Roeg’s Bad Timing. Lionel Dobie has tunnel vision where Paulette is concerned. He hovers. He stares. He makes a nuisance of himself. He is the quintessential Nice Guy(TM) creep. Not everyone’s emotional apparatus is created equal. Nolte is able to access his own depths, and what you get when you go as deep as Nolte does is the ugly stuff, the things you’re ashamed of, the behavior you hope no one ever sees. Actors need empathy in order to be able to play different characters. But there’s a difference between empathy and identification. With empathy, there is still some distance. With identification, there is none. Nolte works from identification.

This was never more true than in his Oscar-nominated performance in Warrior, as Paddy Conlon, whose alcoholism has resulted in years of estrangement from his two sons, Brendan (Joel Edgerton) and Tommy (Tom Hardy). Both Edgerton and Hardy do good work in Warrior, but—it must be said—Nolte obliterates them. The two of them are acting and Nolte is performing an exorcism. There’s a stunning scene where he falls off the wagon, but the brilliance of the performance is in the smaller moments, the way he endures Tommy’s rejection of him, knowing he has it coming. He calls out to Tommy at one point, “It’s okay, son!” and in it is the tragedy of his whole wasted life. He is heartbroken and ashamed. Nolte would make an amazing King Lear.

There’s something about Nick Nolte that reminds me of Herman Melville’s poem “The Coming Storm.” In 1865, shortly after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, Melville saw Sanford Gifford’s painting “A Coming Storm” in a New York museum. The painting shows the vivid shores of Lake George, with a black thundercloud rearing up on the right hand side. (A strange connection: Gifford’s painting was owned by Edwin Booth, famous Shakespearean actor brother of assassin-actor John Wilkes Booth.) Melville found the painting so intense he wrote “The Coming Storm” in response, closing with:

No utter surprise can come to him

Who reaches Shakespeare’s core;

That which we seek and shun is there—

Man’s final lore.

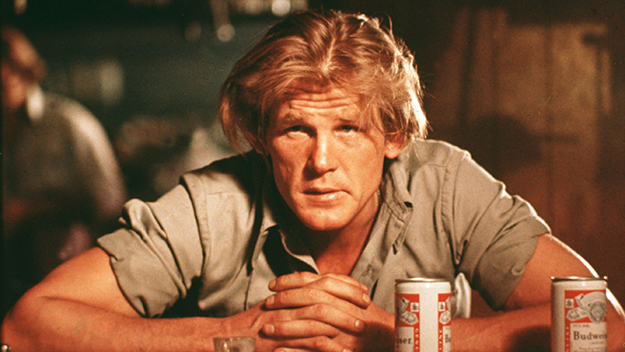

Who’ll Stop the Rain? (Karel Reisz, 1978)

Most actors are fine with showing “that which we seek.” We seek catharsis, we seek knowledge, we seek happiness and love. It takes a great actor to show us “that which we shun.” Nolte is all about the stuff that most of us try to shun, our capacity for ugliness and failure, our limitations.

Grizzled and battered by experience, Nolte’s emotional capacity remains gigantic. I think this is because of not only his familiarity with regret but his willingness to be with regret, to feel the accompanying shame and self-loathing, and then let us see it. Most humans do whatever they can—drink, drug, stay on Twitter all day long—to not have to feel those things, to avoid the lonely nights, described so perfectly by F. Scott Fitgerald in his essay on insomnia:

“—Waste and horror—what I might have been and done that is lost, spent, gone, dissipated, unrecapturable. I could have acted thus, refrained from this, been bold where I was timid, cautious where I was rash.”

Nolte knows those dark recesses of “waste and horror.” A “happy ending” for Nick Nolte will always be highly qualified. Every time he acts, he gives the gift of allowing us to be with “that which we seek and shun.”

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.