Objects of Desire

This article appeared in the October 26, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

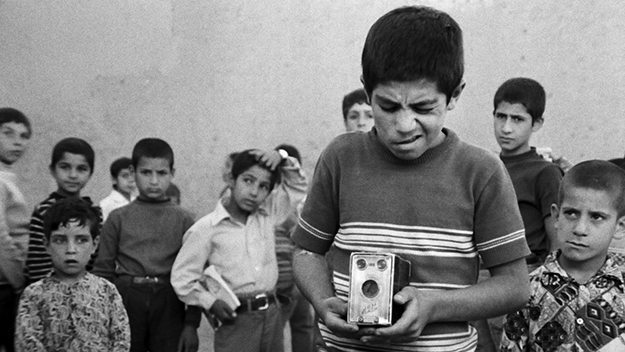

The Traveler (Abbas Kiarostami, 1974)

A cart loaded with fragile treasures jolts at high speed through steep, uneven streets. The opening scene of Downpour (1972), the first feature film by Bahram Beyzaie, depicts the arrival of a schoolteacher in the poor Tehran neighborhood where he has been sent to work. Packed with invention, wit, and breakneck energy, it is also a cinematic arrival for this filmmaker. The unloading of the cart amid a swarm of curious, meddling urchins becomes a playful fantasia of mirrored doubles, frames within frames, and a suddenly haunting procession of ancestors as the children carry their teacher’s family photos above their heads.

Restored from the sole surviving print and released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in 2020, the enchanting Downpour is one of the few prerevolutionary Iranian films readily accessible in the United States. This scarcity makes Iranian Cinema Before the Revolution, 1925-1979—a series playing at the Museum of Modern Art through November 27—a major event. The program, curated by filmmaker Ehsan Khoshbakht, boasts around 70 feature films and shorts, ranging from silent travelogues to 1950s melodramas and 1960s crime thrillers, but focusing most extensively on the Iranian New Wave of the 1970s, an explosion of radical creativity in the years leading up to the revolution of 1979. Many films in the series have been censored or banned in Iran (both before and after 1979) and only rarely screened in the United States. While the more recent work of Jafar Panahi, Asghar Farhadi, and the late Abbas Kiarostami have drawn worldwide attention to postrevolutionary Iranian cinema, pre-1979 films remain largely terra incognita, since the new government’s regulations (for instance, forbidding films that depict unveiled women) banished many movies from screens and drove their filmmakers into exile.

Beyzaie is represented in the series by four films, including recent restorations of two stunning, otherworldly visions: The Stranger and the Fog (1974) and The Ballad of Tara (1979). Combining Persian folklore and supernatural elements with lushly detailed naturalism, they also present bracingly feminist tributes to the fearlessness and resilience of women. Objects in these films—a bloodstained sickle, an ancient sword—hold cryptic, ominous power. In a very different key, fetishized objects are also at the center of two films by Amir Naderi, Harmonica (1973) and Waiting (1974), which opened the series in new restorations. Set in the director’s native southern Iran and inspired by his personal experiences, these two films are hallucinatory in their sunstruck radiance and immersive physicality.

Opening and closing amid the splash of teal-blue waves, Harmonica is as rambunctious and uninhibited as the pack of village boys it follows. It is also an incisive, funny, and caustic parable about how both power and desire corrupt: the boys’ obsession with a shiny Japanese harmonica that one of them receives as a gift begets an absurd pageant of humiliation and greed. In the sublime, almost wordless Waiting, the first object of desire is an exquisite, gold-rimmed glass bowl. An adolescent boy gazes entranced at the sun splintering on its diamond-like facets. His daily errand of taking the bowl to collect ice from a vendor becomes a ritual suffused with ecstatic mystery, centering on the henna-stained hand of an unseen woman that emerges from the narrow opening of a door to take the bowl and return it filled with tinkling chunks of ice. Waiting boldly pairs frenzied religious ceremonies with voluptuous sensuality, as the boy approaches the threshold of forbidden experience.

Cast largely with nonprofessional actors, these films were made under the auspices of Kanoon, the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, which also supported early films by Naderi’s friend and collaborator Abbas Kiarostami. Tasked with making movies for children, these ambitious young filmmakers instead turned out daring, complex, and personal films about children. Naderi wrote the story for Kiarostami’s Experience (1973), another portrait of adolescent yearning and disappointment. The boy in this film works in a photo shop, and his daily routines, menial tasks, and moments of joyful freedom in the city streets unfurl in a succession of elegant black-and-white compositions, often framing him in windows or mirrors. Experience is, among other things, a meditation on photography, also the subject of one of the best scenes in Kiarostami’s first feature, The Traveler (1974). In another tale of obsession, a boy named Qassem (Hassan Darabi) has his heart set on making a trip to Tehran to see a soccer match. One of his schemes to hustle the money he needs for the journey involves charging other schoolboys for taking their pictures, though he knows the camera he’s using is broken. He’s good at faking it, however, eliciting grins and poses that are immortalized not by his camera but by Kiarostami’s. Qassem is shameless about cheating, lying, and stealing, but his journey is so masterfully composed of agonized waiting, near-misses, exhilaration, and crushing disappointment that it is impossible not to become complicit in his monomania.

Launched in the 1960s by a generation of socially conscious and stylistically adventurous filmmakers who rejected the formulas of popular commercial genre cinema, the Iranian New Wave was intensely collaborative. Kiarostami designed the striking credit sequence for Masoud Kimiai’s Gheysar (1969), in which we see illustrations of Persian warriors that turn out to be tattoos on men’s arms and torsos. The story, tracking the title character’s quest to avenge the rape and suicide of his sister and the murder of his brother, is filled with patriarchal talk of honor and manhood, but the visual style is electrifying, with violent scenes (including a shower-stall murder that nods to Psycho) unleashing slashing storms of blurry motion and rapid cuts. Gheysar was a pivotal film in launching the New Wave, but even more consequential was Kimiai’s The Deer (1974), whose furious social critique and call for revolutionary action made it political dynamite. After its premiere, the Shah’s government forced the director to shoot a new ending in which the two main characters surrender to the police, and add dialogue that turned one of them into a bank robber instead of a radical. (MoMA will screen both the original and imposed endings.)

The film opens with Ghodrat (Faramarz Gharibian), wounded and carrying a suitcase full of cash, seeking out his old school friend Seyed, only to find that the once upstanding student has become a ravaged junkie, sunk so low that he pushes drugs to schoolboys in exchange for free heroin. Behrouz Vossoughi, the handsome, ultra-cool avenger of Gheysar, transformed himself physically to play this moral wreck. The heart of the film is the passionate bond between the men, and the loving rage with which Ghodrat exhorts his friend to stand up and fight back. Seyed works at a schlocky commercial theater, where his girlfriend acts in crude popular stage plays, portrayed as cheap, escapist entertainments. By contrast, the laundry-festooned courtyard of the tenement where Seyed lives is a riveting theater of poverty, injustice, and desperation.

Stylistically, there is a huge gulf between the volcanic emotion and kinetic energy of Kimiai’s films and the implacably slow, minimalist cinema of Sohrab Shahid Saless, with its muted colors and nearly mute heroes. But anger burns below the cool surface of Still Life (1974) and Far from Home (1975), both of which gaze unblinkingly at working men who are exploited, discarded, and above all ignored by callous economic systems. Filmed in Germany, Far from Home follows a Turkish guest worker through the numbing routine of operating a metal press in a factory, riding the metro, and living in cramped quarters among other immigrant men, deprived of both intimacy and privacy. That he can barely speak German condemns him to inarticulacy—though the elderly protagonist of Still Life, despite remaining in his homeland, is a man of equally few words.

Employed by the railway in what appears to be the precise middle of nowhere, Mohammed (Zadour Bonyadi) spends his life manually raising and lowering traffic barriers at a track crossing, rolling and smoking cigarettes, drinking tea, and eating silent meals with his wife, who painstakingly weaves traditional carpets that no one seems to want. We grow accustomed to repetitive routines and petty frustrations—in one scene, the aging wife spends some 10 minutes patiently trying to thread a needle. When Mohammed gets a letter impersonally informing him that he is henceforth “retired,” he doesn’t understand the term. The man who gives him the letter explains that it means he can now go have “fun”—another word that’s presumably not in his vocabulary.

Sullen skies brood over bedraggled landscapes, and the walls of the couple’s single room are blue, as though stained with sadness. But this austere film surprises with sly glints of deadpan humor and images of arresting beauty, like a shot of the old signalman looking down the tracks at the light of a disappearing train in the amethyst dusk. At the end, he stands in an empty room and peers at his reflection in a tarnished mirror, in a solitude beyond the reach of words.

From internationally recognized films like Still Life (which won the Silver Bear at the 1974 Berlinale) to truly obscure flicks like the cheap, sensational genre movies surveyed in Khoshbakht’s essay collage filmfarsi (2019), the MoMA series demonstrates both the fragility and resilience of cinema. Although the revolution of 1979 marked a rupture in Iranian film history, a constant through line before and after that moment has been artists’ ability, in the face of overwhelming restrictions and political pressures, to continue to make passionately original and honest films. Now, they only need to be seen.

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy. She has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere, and wrote the Phantom Light column for Film Comment.