Interview: Yervant Gianikian

In February 2018, the Italian artist and filmmaker Angela Ricci Lucchi passed away following over 40 years of politically charged moving image work with her longtime partner and collaborator Yervant Gianikian. With their radical use of archival imagery—concerning oft-overlooked instances of 20th-century violence—the duo were pioneers of a form of essayistic, montage-based filmmaking that subjected found materials to an assortment of rephotography and extra-sensory effects. As evident in such landmark works as From the Pole to the Equator (1987), comprised of repurposed footage of colonial expansion originally shot by the Italian filmmaker Luca Comerio, or a series of “scented films” that paired the couple’s frequently troubling imagery with a variety of soothing fragrances, the pair skillfully worked to interrogate all aspects of the medium.

In the time since Ricci Lucchi’s death, Gianikian has embarked on a more personal journey through the couple’s own archives. Angela’s Diaries is a thus far two-part tribute to their working relationship in which Gianikian combines footage of the duo’s personal and professional lives with corresponding excerpts from Ricci Lucchi’s handwritten notebooks and images of her luminous watercolor sketches. In my report for Film Comment from the 2019 International Film Festival Rotterdam, I described the series’ first entry, Angela’s Diaries: Two Filmmakers (2018), as both “a primer on this sorely under-recognized duo and an exquisite work of personal-poetic nonfiction.” The follow-up, Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two, continues the excavation but pivots from the earlier film’s focus on the couple’s home life and European travels to their extended tour through the U.S. in the early ’80s (with stops at a variety of underground film organizations in New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco) and a more recent, eye-opening trip to Jerusalem. Across both films, a vision of life, love, community, and art emerges that’s impossibly tender—even inspiring.

Following the presentation of Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two at IFFR 2020, Gianikian and I began an email exchange about this unique ongoing project, its symbolic resonance, and how, moving forward, we may be forced to rethink notions of the cinematic experience.

In the first scene of Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two there’s an interview with a man who speaks about the “cellar” where you and Angela kept your archival footage. Can you tell me a little about this cellar?

The cellar is a symbol. It is the basement of the soul. It is a metaphor for our research through frames and archives, and the reimagining of each which is at the heart of our work. Our “cellar,” in this case, alludes to the inner space made of images that will emerge again, which tell of the violence of the 20th century. The materials seen in our films and those not seen are part of an archive project that I promised Angela that I would carry on.

Is there an actual physical place where you and Angela stored footage over the years?

All our private films and video are in our flat in Milan, where we live and work with our analytic camera.

Can you expand on this idea of the analytic camera?

For us, “analytic” refers to the process of examining and re-filming frame by frame the archive materials themselves. This approach allows us to descend into the depth of the film frame, to hone in on details, and to intervene on the speed and colors of the image. We used to bring home film materials that we had discovered in our warehouse and work with them through this analytical process. In the second chapter of Angela’s Diaries, for example, I used some sequences from our film Karagoez-Catalogue 9.5 (1979-81), which comprises materials concerning Jerusalem before World War I, during the Ottoman period, that we originally worked with in this way.

Can you talk a bit about embarking on a second chapter in this project? I know you’re now referring to it as a diptych, but was it always conceived as a multi-part work?

Even while making the first Angela’s Diaries, I still didn’t know I would make a second part. The second Angela’s Diaries arises from the urgency of revisiting our world of past and present, and our political and historical commitment. The possibility of making a third part of the film is inherent in the power of the materials collected throughout our lives: the frames of the archive, the diaries, the readings, the drawings, the watercolors. The need to narrate violence is strong. For me, among other fundamental questions of the work, it is central to give Angela a voice again. And this means first and foremost using her writings as a map and compass of mine and our time.

Can you tell me a little bit about Angela’s knack and passion for documenting your everyday lives? Based on the amount of footage in just these two films, you two always seemed to be filming or taking photographs. Was this something you and her discussed? And had you (or her) ever revisited any of this footage before beginning work on these films?

Angela loved taking pictures with a 35mm instant flash camera. Sometimes when necessary she used the video camera or 8mm, Super 8mm, or a 16mm Kodachrome camera. She almost always drew and wrote in her diaries what we saw at home or on the road. I was usually the one filming. Daily life was the action of filming everyday. It was an act that came naturally to us. We almost never reviewed our private films. Sometimes, while working, we would decide together what we thought was important to say. For example, during the war in the Balkans: it was while in the studio that we filmed the archive material related to war with our 16mm analytic camera that became From the Pole to the Equator. We always had a video or film camera ready to use at home or while traveling.

The first section of the film documents your travels around the U.S. in the ’80s. There’s some incredible footage of the experimental film communities in various cities on the West Coast during that era—Los Angeles in particular. Can you talk about forging and maintaining these relationships over the years, and how they brought you to places all over the world? I’m also curious if you have any remembrances about this time spent in the U.S.: the people, the venues (many of which are gone), the cities in general?

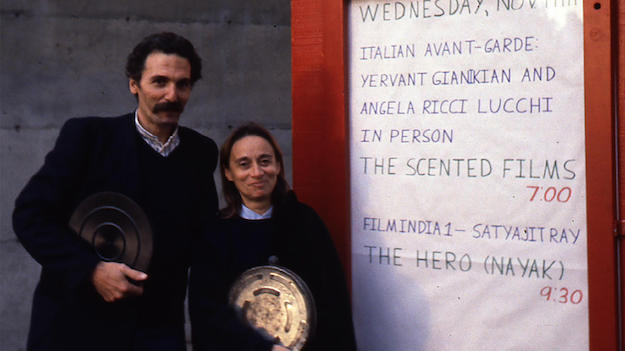

Through the thousands of frames in Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two our parallel diary emerges: Angela’s writing and my images. To tell of my impressions of those places and encounters today, beyond the film, means digging and relying on words. For example, I remember perfectly well that in 1979 we had been invited to the Third International Avant-Garde film festival in London, at the National Film Theatre, where we showed our “scented films” for the first time abroad.

We had brought some pictures of the South Tyrolean toys for the occasion, recovered in the places where Gustav Mahler had composed “Song of the Earth.” And we also had with us the images filmed at the Lombroso Museum of Criminology in Turin. Cesare Lombroso’s work has always impressed me. That time we were hosted in London in a room where four festival guests and a cat slept. Our perfumed film had a great reception. At the screening there were many filmmakers that we didn’t know, like Larry Gottheim, Janis Crystal Lipzin, Grahame Weinbren, and Roberta Friedman. Soon after, Jonas Mekas invited us to New York and Anthology Film Archives, and Janis wrote a nice text about our scented films that appeared in Cinema News [a bi-monthly magazine published by the Foundation for Art in Cinema].

We arrived in New York City at 7 p.m. and Angela had a very high fever. We went to a doctor; Jonas and I were very worried. He telephoned us continuously in the house we were staying in on Canal Street, very near Anthology. Despite Angela’s status we managed to make that important screening. Mekas said: “The movies are good, I never got bored.” Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote about it in the Soho News. In the meantime, Terry Cannon, perhaps through Jonas, organized a screening at L.A., at his Filmforum in Pasadena and another at the Cinematheque in San Francisco. At the Los Angeles airport we received a nice surprise when Roberta Friedman picked us up.

There were many people in attendance for our scented films screening at Pasadena Filmforum—there were even Armenians in the audience. One of them said: “Yervant, I have not smelled Armenia.” There were people in the audience even from San Diego! Terry was astonished. We lived with Terry and his wife Mary for a bit. This began a life-long correspondence with Los Angeles. Through them we discovered Venice, Hollywood, Beverly Hills… The color of the sea and the light were surprising to us. The flavors of Mexican and Japanese cuisine were also a surprise. Mary took care of Angela, who did not speak English. They spoke to us in French. We promised to meet again.

One thing that Angela did not mention in her/our journals during this time is that we rented a car and went to Montebello to find Aristakes Djianikian, my father’s cousin. He had fled Iran just before Komeini’s advent. His daughter had gone to pick him up in Tehran after he was widowed. I had seen him as a child in the Eastern Alps where my parents lived. He was sick and my father treated him. He was the confectioner of the Shah of Persia. It was a short and exciting meeting. He was surprised at my visit; like me, he had tears in his eyes. I recorded some footage of him. He lived in a beautiful house with a central patio. He was surrounded by his grandchildren.

After our visit to L.A. we rented a Datsun without automatic transmission, and we made the drive up the coast for San Francisco. We stopped in Big Sur, at Henry Miller’s bar, as Terry and Mary had suggested. In San Francisco, we met friends, then went on tours in Chinatown. We stayed with Jeffrey Skoller and Stephy Beroes, who gave us the beautiful series of postcards of the attack on President Ronald Reagan that appear in Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two. The screening at the San Francisco Cinematheque went very well. With Carmen Vigil and new friends we celebrated at the sea on July 4th. It was an unforgettable afternoon.

You mentioned earlier that you and Angela never looked at your footage. Can you tell me what it was like when you saw some of these images for the first time? I imagine it was emotional. Did you already have an idea that you wanted to make a film from this material, or did you only realize that once you began to look at it?

After Angela’s departure I immediately had the feeling to continue our work together. I had never looked at the materials we shot, but I had precise memories of having filmed with Angela: our private and family events, and also our work related to violence and the archive. At the same time as I was watching and rediscovering the footage, I immediately began exploring Angela’s diaries (written mostly in black Chinese notebooks with red corners), and her drawing albums, which contain drawn and written diaries along with long rolls of watercolor sketches. Some new things emerged from her final writings and drawings: her time on the Gothic Line [a German defensive line of the Italian Campaign of World War II] as a young girl, in the same places described by Rossellini in Paisà (1946); her time in art school in the early ’60s with Oskar Kokoschka in Salzburg, pages all about him, Dresden, and South Tyrol; the summer house of Gustav Mahler, his love for Alma Mahler, and him making a doll that looked just like her—the artist’s obsession; Angela’s “crazy kids” in a school for special needs children and her decision to give up art to work for the community and help these kids, only to return with even greater energy to our work together.

How did you go about deciding what footage you wanted to include in each film? Did it depend on matching the images with the material in the diaries, so there could be a correspondence between the two? And how did you go about structuring the film around these episodes from your lives?

I started looking at all the materials I had at home and making copies of them. As I watched, I took note of the hundreds of hours of video in various formats, and of films in various formats. As far as films are concerned, I had high-definition digitalization of the 8mm, Super 8, 16mm, and 35mm footage. In March 2018 I began to think about how I intended to do the first Angela’s Diaries. In that month I began to rummage in her written diaries, notebooks, bound booklets, drawn albums (rolls from four meters to 18 meters long and 75 cm high) to copy the parts that were relevant, to mark those that could possibly serve me. I had the feeling that I was still working with her, as we always had over the years—sensing, somehow, that we were continuing the work together.

On the basis of what I was discovering in her private diaries, I filled notebooks with descriptions of the film materials made by us both together, those that related to the diaries. It was a long catalogue of filmed images. What I was seeing seemed new to me, even though we had been the ones to shoot the scenes of our lives. I was looking for the correspondence between the filmed images and the handwritten words of Angela. I structured the two films following some recent and not-so-recent moments in our life as artists and filmmakers: public presentations of our work shown in museums, such as our “Non Non Non” exhibition at Hangar Bicocca in 2012; our installations at the Venice Art Biennales in 2001 and 2015; our great retrospective at the 2015 Beaubourg; and our six-channel, 400-minute Journey to Russia installation at Documenta 14 in 2017, our longest work on the Russian avant-garde, which we had started in 1989.

Much of the first film documents our travels to search various archives, mixed with images of our private life between our home in Milan and the countryside in Piedmont where we keep our personal archive. With Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two I wanted to remember our American travels, especially the two-month tour of 1981 we just discussed. There was a great humanity in the filmmakers community who supported us during the trip, a tour where we sometimes felt lost, and during which Angela was sick. It was important for us to document the great commitment and mission of this community, which we saw while traveling with our films, and which helped keep alive an era of independent cinema.

We filmed all the people we met on the tour, all the groups linked to the American avant-garde who gathered around our screenings. We recorded all the cinemas and screens where we showed our films. Pasadena’s Filmforum was in a former bank, the safe at the entrance and the old dark wooden doors were still in evidence. Outside L.A. we photographed some of the ancient historical cinemas: the El Rey, the Gordon, the Alcazar Theatre in Carpinteria. I also inserted some sequences of the ‘scented films’ that we were showing during this time: Cesare Lombroso: Scent of Carnation (1976), made in the Turin museum of Lombroso; parts from our first 9.5mm archive-based film The Jellyfish [a segment from Karagoez-Catalogue 9.5, filmed in the Oceanographic Museum in Monaco circa 1910]; and Essence d’Absynthe (1981), a primitive erotic film.

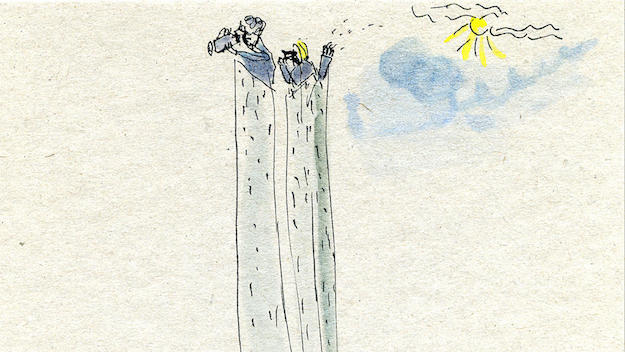

Chapter Two also features footage from two retrospectives at MoMA commissioned by William Sloan and Mary Lea Bandy. During the first, in 2000, Angela made a watercolor of us and all the guests at the museum restaurant. During that visit we also ate with Bill and his wife in the top floor restaurant of the Twin Towers. Angela made a color drawing of the two of us atop the towers as we filmed, which I discovered while researching the material for Angela’s Diaries—you see it in the film. (Angela always made watercolors of the places we didn’t film or photograph, thus filling in what was missing from our diaries.) On September 12, 2001, Bill sent us a dramatic email of what had happened to him on September 11.

The 2009 MoMA retrospective closes the American part of Chapter Two. We opened the exhibition with our film about Nazi toys, Ghiro Ghiro Tondo (2007). It also featured sequences from our WWI film On the Heights All Is Peace (1999), with Austrian and Italian materials from Luca Comerio’s original negatives, and a scene of the stray children in Soviet Russia from our film Oh! Man (2004). (Mary Lea Bandy wanted to inaugurate the new MoMA with Oh! Man, which she saw in Cannes in 2004, but political reasons kept her from succeeding.) In the harsh winter of 2009 Bill and Gwen took us to their favorite Japanese restaurant in New York. Looking at this footage was my first time seeing these melancholy images of our two old friends.

Were you surprised by any of the other footage you came across?

There were many surprises along the way. I was constantly surprised by what came out of the videos that I was rediscovering. It was all inextricably linked to Angela’s diaries, which in turn duly recounted and explained the public and private events that happened in the filming. A curious example: the footage in Moscow from August 1993, when we were searching for archival documentary materials on Austrian WWI prisoners in Russia. To my amazement, I came across footage shot in the apartment we had rented, in which a group of Azeri engineers reappear at dinner, singing a song of the Don Cossacks at the top of their lungs. (This footage appears in Chapter One.) That experience sort of sums up the Russian situation after the fall of communism.

To quote from Angela’s diaries: “A driver is waiting for us, he is an ex-colonel, reservist, and psychologist with the Red Army: Yuri. Our landlady, Tatiana, also sees to our meals. She is from Baku, a Russian literature teacher, and is always present. She supports Boris Yeltsin and is nostalgic about pre-revolutionary tsarist Russia. We will have dinners inviting lots of unknown guests over the next few days. In fact, the first evening, we zoomed straight from the airport to a large table of guests from Baku . . . We will discover later that our expensive daily boarding fee is funding this stream of dinner guests, the landlady’s friends. Our fellow diners are practicing Marxists, who don’t renounce their faith. It’s very different here from Saint-Petersburg’s cultured society, with filmmakers, writers, and poets we’ve met. We feel uneasy. We want to see as much of the archives as we can and leave as soon as possible. Yuri takes us to the military archive, where we noticed a bullet hole in his Lada’s windscreen.”

One other surprise: In Chapter Two, shortly after the start, the Italian comic actor Walter Chiari appears, who was the main actor in Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima (1951), with Anna Magnani. He also plays the part of “Silence” in Orson Welles’ Chimes at Midnight (1966), and in the same year acted in Michael Powell’s They’re a Weird Mob. In 1987, Chiari wanted to accompany us to Armenia, on a bizarre journey which is recounted a bit in Chapter One. This is the scene with the smoke in the glass of wine. It was surprising for Ava to have to drink a glass filled with wine and cigarette smoke. But Ava and Walter ended up having a romance from 1954 until 1958. It was the beginning of the notion of the paparazzi, cf. La Dolce Vita (1960), by Fellini.

Can you tell me a bit about the Jerusalem footage in the second half of the film? After spending much of the movie detailing your travels in America, it seems like a fairly political gesture to shift to the Middle East.

This section is our 10-day diary in the heart of the un-restrainable decline and gradual disappearance of the Christians of the East due to tensions and war: religious tourism, pilgrimages, its changes (e.g. absence of rich countries). Some had been traveling on foot for six months. Two things in Angela’s diaries upset me: first, the trip to Jerusalem in 2007, where we were on Easter holiday to film the religious ceremonies of the Christians of the East. While there we shot a considerable amount of materials on Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, and Coptic Orthodox Ethiopians, and we had prepared ourselves by reading a multitude of ancient and recent texts on the Crusades, while also collecting a lot of iconographic material—primitive images of Ottoman Jerusalem. Angela’s diary of this trip painfully revealed to me the reasons we never completed the film. The title of the last section of Angela’s Diaries: Chapter Two is “Gothic Line,” which comes from a diary entry Angela wrote in 2017 that recounts the history of her family on the front line of the Second World War, when she was just a little girl. This text, which is read in the film by poet Lucrezia Lerro, is accompanied by a 10 meters long scroll of watercolors that collects all the elements of these family memories as they relate to WWII. The drawings and colors of the war are thus images seen by a little bambina who reconstructs the lost memory of events.

The other upsetting thing concerns the initial scenes of the film, when Enrico Ghezzi, the critic who describes our path in the first scene of the film, which we discussed earlier, shows the physical self-destruction and decomposition of some nitrate material—scenes from our film From the Pole to the Equator. Ten years after we made the film I opened a box of the original nitrate flammable materials used for this film, which was about WWI, and I saw that the 35mm film was almost completely decayed. We made a film about it—a sort of report on this discovery called Transparencies (1998). Jean-Luc Godard used some of these parts, and also parts of the train sequence in From the Pole to the Equator (without asking permission) in The Image Book (2018).

Since we began this correspondence in January, a lot has changed in the world. I’m wondering if you can reflect a bit on what a global pandemic such as COVID-19 might mean for the future of cinema? So much of Angela’s Diaries concerns community and friendship amongst peers and fellow cinephiles. Do you think we can regain what’s been lost during this pandemic?

It would be nice to be able to go back to the times of community and friendship between peers and cinephiles described in Angela Diaries: Chapter Two. At the moment this is unthinkable with the global pandemic. For the future of cinema, are we moving toward the solitary spectator? After all, most of the film festivals are currently streaming films for individual viewers in their homes. I remember the advent of family cinema, when in 1922 Charles Pathé marketed the very small 9.5 Pathé Baby projectors together with a series of films, fiction and documentaries, for the wealthy bourgeoisie. And then later there was Stan Brakhage, who was shipping for a few dollars some of his 8mm films, to those who asked for them. He even managed to make contact copies at home—another prophetic example. But I hope we return to the common vision of shared experience and collectivity. If, however, the pandemic persists, one may have to think of a new cinematographic vision, a new architecture of the projected image.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is a member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.