Interview: Sofia Bohdanowicz & Deragh Campbell

In Sofia Bohdanowicz’s first feature Never Eat Alone (2016), actress Deragh Campbell plays Audrey, a young woman who helps her grandmother try and reconnect with an ex-lover. Based partly on Bohdanowicz herself, the Audrey character would reappear in the director’s subsequent short film Veslemøy’s Song (2018), in which Campbell searches the New York Public Library for a rare recording of a song by Kathleen Parlow, a music instructor who taught violin to Bohdanowicz’s grandfather. Returning to Audrey for a third time in MS Slavic 7, Bohdanowicz’s latest feature—this one co-directed with Campbell—again finds the Toronto-based filmmaker exploring her family history through a fictionalized framework that draws equally from the archive as it does the well of firsthand experience.

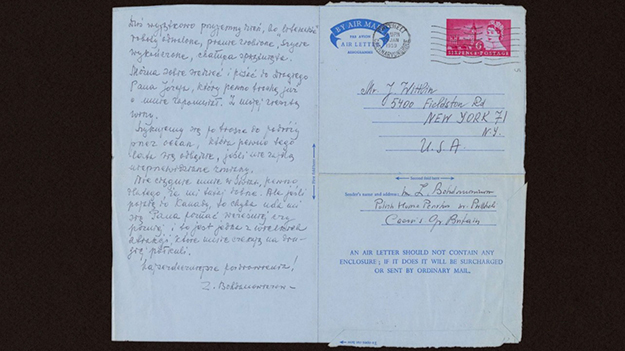

The film opens as Audrey sets off from Toronto to Cambridge to research letters sent by her great-grandmother, a Polish poet, to author Józef Wittlin while the two lived in exile in North America. These letters, written by Bohdanowicz’s real-life great-grandmother Zofia Bohdanowiczowa, form the backbone of the story; seen variously on the page, translated on screen as subtitles, or projected on the wall of Harvard’s Houghton Library (the film’s title refers to the reference number of the correspondence), the words and their material record become a powerful conduit of memories and emotions. As she reflects each evening on the letters and their heartfelt declarations, Audrey appears impelled to reconcile the courage at the heart of the correspondence with her own unspoken melancholy. In flashback, she attends an anniversary celebration, where her and her aunt (Elizabeth Rucker) fight over her role as the literary executor of the estate, a role we see Audrey take to with curiosity and desire. With quiet resolve and empathy, so too do Bohdanowicz and Campbell investigate Audrey’s longing; together they’ve cultivated a character that at this point can’t simply be read as a surrogate (if it ever could), but as a complex and ever-evolving figure in her own right. Through her, Bohdanowicz and Campbell manage to open a space for thought and introspection that precious few films afford.

Following the premiere of MS Slavic 7 in the Forum section at the 69th Berlinale, Bohdanowicz and Campbell sat down to discuss the biographical inspirations behind the film, the co-direction process, the evolution of the Audrey character, and, for an actress, the strange experience of playing a version of your director on screen. MS Slavic 7 screens in New Directors/New Films on March 30 and April 1.

How aware of Zofia’s life story were you before you began working on this film? She’s your great-grandmother, but were you familiar with her history before digging into these poems?

Sofia Bohdanowicz: Yes, fairly familiar. Like you said, she’s my great-grandmother—I’m named after her. Zofia was a poet who was ousted from Poland during World War II. She was living in Vilnius and then had to flee because the Russian Red Army and the Germans were taking over. So she lived throughout Europe, having fled during the war, and ended up in North Africa and eventually Wales. At that point my grandfather, Andrej, wanted to move to Toronto because as Polish people working in the U.K. they were discriminated against. So they came to Toronto to find work and settled there. Zofia loved the countryside—she loved living in Wales and wrote a lot of really beautiful poetry there, but then when she came to Toronto she had a really hard time acclimatizing to an urban setting. She wrote a series of poems that have been collected in an anthology of Polish poets living in Canada after the war, and in it I found a series of poems that she wrote about living in Toronto. I based a short film, Dundas Street [2012], on one of these poems, which is about coming to Toronto as an immigrant and living close to a slaughterhouse. There were lots of smells and sounds and things that she wasn’t used to. And her husband died within eight months of coming to Canada, so that was really hard. I’ve made five short films based on her work, so I’m pretty familiar with her poetry. The reason why I started making films based on her work is that even though it’s decades later—she was writing these poems in the ’60s, and I unfortunately never got to meet her—I could still find myself identifying with her words and how she relates to the city. And because I’m named after her, I kind of feel this pressure, or weight, or like I’m this keeper of some kind of historical flame. And with regards to this film, she isn’t as recognized as Józef Wittlin, so it’s important for me to get her work and her history out there as well.

How and when did you come across the letters we see in the film?

SB: I was just Googling her name. That’s actually how I found her poem “Dundas Street.” I like to do a lot of snooping. I found her name in an online archive and saw that there were 25 letters that she had written to this man named Józef Wittlin, and his name was familiar because in that anthology that I was talking about she had written a poem about him and him coming to Toronto to meet her. They had only met once and she wrote this poem about them walking together in High Park.

Deragh Campbell: Which is the poem at the beginning of the film.

SB: Yes, “In Silence.” And in that same holding is a letter from Hannah Arendt, which is really interesting. I got Harvard to scan the letters and the Polish Consulate to translate them, and once I had the translations I realized how rich they were and from there I started talking to Deragh about them.

At what point did you two realize that Audrey would be an ongoing character, and one used to continue to explore Sofia’s history?

SB: I found the letters really interesting, and knew I wanted to utilize them, but Deragh came to me and pitched the concept.

DC: I think that we had two separate goals: one, through the structure of the film, to sort of separate the image of the letters from the material itself; and then from there to deconstruct Audrey’s thoughts about the letters, all to give the audience different access points to this information. So you have the image of the letters, you have Audrey’s reactions, and then eventually you’re able to read the translations and hear a recital of them. So we knew we wanted to have different ways of presenting the narrative within and through the letters. But I think with Audrey we wanted to develop this character to find out a little bit more about her, what was driving her. Because she’s a little bit mysterious. She has this avid curiosity but you’re a little unsure—like, she’s always alone, and she’s curious, but we don’t know exactly where this curiosity comes from, if it’s an impulse or something else. We wanted to spend more time with Audrey and dive into her psychology a bit more, and so I think through this you really see, especially in the monologues, how much is at stake for her—you see her move through extreme excitement when she has an idea and then you see her become really dejected when she isn’t able to articulate herself. I think she’s a person that can feel extraordinarily isolated from other people, and so connecting with this work of her great-grandmother’s—much like Sofia was saying before—is a necessity for her to feel like a person.

And it was your idea to readopt the character after Never Eat Alone?

DC: I think we always talked about Audrey continuing on. I’m not sure when that happened.

SB: We actually shot MS Slavic 7 before Veslemøy’s Song. Veslemøy’s Song came out first but that’s just because it was a lot easier to cut together, obviously, while MS Slavic 7 has taken a lot longer. But we had just such a smooth and alchemic working relationship, and I just keep continuing to find interesting stories on the maternal and paternal sides of my families. It just seems like such an interesting and rewarding vehicle to use and to continue developing this character with Deragh, because she gives so much as an actor. Before this film she gave herself a reading list, and she was planning all of the different outfits that she would wear on different days in the archive. It’s all kind of beyond what an actor usually offers on a project, which is why the film evolved into a co-direction. Because I realized that she had a lot of the answers—when we were editing especially but throughout the shooting—ones that I didn’t have, which was really interesting and really exciting. But we like the idea—you know, like Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel series. You kind of just make another film and there’s no recognition of the past, though she’s still the same person. And we have other films planned for this character. We’re not bored of it yet.

How did the co-direction process play out? Was there a division of duties on set?

DC: It always co-written and co-produced, but on set Sofia was the director and I was the actor. Also, Sofia was shooting it and doing sound.

SB: I had a Tascam around my neck. It was pretty funny.

DC: Yeah, it was just the two of us. I was actor and art department [laughs].

SB: And Calvin [Thomas]—our producer—came in to give us a hand from time to time, but Deragh was always there to chime in and make sure that the concept was sound and we were always on the same page. I think that’s what’s really great about working together is that we don’t have a lot of ego—it’s never like, “I’m right, you’re wrong.” It’s about making the right decision for the project so that it can be better. When I sit down to edit a film I usually know where it should go, and I remember editing the first 20 minutes of this film together for Deragh and presenting it to her and she was like, “I think some of this works, but some of it doesn’t.” When I did that first pass I was like, “Oh my God, I don’t know if this is going to work. Did we do all of this work for naught?” That’s how it always feels when you start editing a film, but Deragh offered to sit down with me once or twice a week and edit with me and it was then that I realized that she had been a very natural collaborator all along and had a lot of those answers that a director has. So that’s when we decided that the film would be a co-direction.

DC: I think too in the way that we work together it’s always about deciding what’s best for the project, not about defending an idea because it’s your idea. It’s interesting that the idea of giving up ownership was always a necessary part of the process.

SB: Yeah, it’s always a very easy thing. It’s not difficult and I guess that’s why we continue to work together, because we have lots of things that we like developing together and it just kind of flows very easily, more so than it has been working with other people.

It definitely seems like the character is leaving more and more of an authorial stamp on the projects, which I gather is a result of Deragh’s contributions.

SB: Yeah, she would swoop in when I was unsure, and I would swoop in when she was unsure. It was a really nice process.

At what point did the anniversary party plot line came into it play? Was that in the script from beginning, or did that develop as you realized that Audrey’s journey might need an additional dimension?

SB: Deragh had already pitched the main idea, about a literary executor working in an archive, looking at her great-grandmother’s letters. But then my great-aunt and -uncle’s 60th wedding anniversary happened to be that June, and we were shooting in July. It was at the Polish Combatants Hall in Toronto, which is this well-known Polish hall that’s really intense, with a beautiful stage and a red velvet curtain. So I asked my great-aunt and -uncle, “Can I bring my friend Deragh and also film some things?” I told them I’d film the party, but I also just sneakily filmed Deragh as she sat down with my family at the head table beside my parents. There’s actually a shot in the film with my dad videoing the stage behind Deragh and she just kind of seamlessly fit right in. At that point we weren’t entirely sure about the full structure of the film, but what I did was got her to have different reactions to things, to speeches, and I just shot as much as we could. I had her sit in different places in the bar looking happy, looking sad, clapping, interacting with people. I knew it would be useful for the film, but I didn’t know at that time how useful it would be. What was funny about doing that was that when we completed the film and we knew that it was going to screen at the Berlinale, we had to get in touch with everyone who was at the party and tell them I had been filming them. But that’s why all that footage is so natural. It ended up being very rich. Once we developed the film some more we decided to go back to the Polish Combatants Hall an extra day to shoot all of those scenes with Elizabeth Rucker as Audrey’s aunt.

Once you looked at it you felt like it maybe needed another dramatic element?

DC: A dramatic element, yeah. Or we just needed a scenario to justify the different places we were in. But thank goodness we did get that footage at the Polish Combatants Hall. It would’ve been so much more complicated to represent the three generations. Showing Audrey with her family and having her bring that psychological pressure into the presence of the letters hopefully shows a bit more of what’s motivating her.

SB: It was an interesting way to build a kind of tension in the film. We shot a lot and we had a concept, but the arc was really developed with us editing together. One thing we wanted to explore is that within family history there are people that are like, “Yeah, it’s family. It’s inherent. Who cares.” And then there are some people that really care about it. But when someone dies and there’s an estate, everyone’s all of a sudden interested, and jealousy can arise. As far as Audrey and her aunt are concerned, I think Audrey is a little entitled. She’s been given this position as a literary executor, she’s not really sure where she wants to go in life, and maybe her aunt feels a little left out and threatened because her mother has passed away and didn’t give that title to her. Also I think Audrey has this attitude that just because she cares about this stuff more that she owns it more, but that actually isn’t true. Something else that we discovered is that Audrey embodies a kind of self-doubt, like when you’re trying to build something creatively, and especially with regards to filmmaking. When you say, “I’m going to be a filmmaker, I’m going to make films,” there’s no one that hires you. You kind of appoint yourself to that role. And there are a lot of levels of self-doubt to that. Like, who’s going to pay me? Can I actually do this? I feel like in a lot of ways that the character mimics the psychological wars that you have with yourself when you’re trying to self-actualize. So she really has two purposes.

Deragh, as an actor, can you tell me a bit about how you approach a character that at least on some level is a representation of the director you’re working with?

DC: I think that Audrey certainly began as a stand-in for Sofia. In Never Eat Alone it was in a very direct way. That was me acting as Sofia in interactions with her grandmother—her living grandmother.

SB: Grandmother on the maternal side, because MS Slavic 7 is a film that’s about the paternal side. I can draw you a family tree later… [Laughs]

DC: It’s funny because in Veslemøy’s Song you can see my face on Audrey’s passport, but with her name, Audrey Benac, and Sofia’s information. [Laughs] But it became very literal, this identity fusion. I see a lot of myself in Audrey. I grew up with successful artist parents and I think I always thought of myself as an artist without really having done anything. There was a point in time when I realized I hadn’t really developed the discipline to really start and finish something. I think Audrey has this desire to learn and perhaps build something, but when she encounters the aunt and the aunt more or less says that she’s silly and she’s a child, that Audrey for the first time is like, “You know what? I’m not going to just stay with an idea. I’m going to stick to this and I’m going to put forth the work in order to produce something.” She visits the letters, she thinks about the letters, and she’s able to draw conclusions from them. In a weird way I think that’s a feat of strength, you know? Elect to do something and then go and do it without anyone asking you to do it. I don’t know exactly where that willpower comes from.

SB: Yeah, it’s this moment where she’s learning how to assert herself. She’s finding her voice and that’s very much a part of being on an artistic journey or trying to self-actualize. Not only do you have self-doubt but you have people that are telling you, “Are you sure?” Or maybe that you can’t or you shouldn’t do that.

DC: And also you’re saying that to yourself, probably.

SB: Yeah.

DC: Like, is that something that’s worth doing? Sometimes I’ll give up on something pretty quickly because it’s very hard for me to continue to feel that it’s meaningful. You need a certain perseverance to move through doubt and move through thinking something is kind of meaningless to hopefully arrive at a more complicated and nuanced meaning.

Was there a certain point for you, Sofia, that you knew you had given this character over to Deragh?

SB: I think from the get-go. Even in Never Eat Alone, Audrey is such an amalgam of different family members. At first when I was pitching the idea of having someone play me or a version of me in that film to Calvin, I was like, “Can I do that? Is that weird or is that very vain?” But then I started to think of this character as someone who was built out of different family members. She has my cousin Audrey’s name; the apartment she lives in [in Never Eat Alone] is my cousin Grace’s bachelor apartment; and she wears a lot of my family members’ clothing. But also in MS Slavic 7, there’s a part where she’s wearing a scarf and holding a purse—that scarf and purse belong to my maternal grandmother. And she’s holding Zofia’s cigarette case. I guess I see it as a tool or a way to tell stories that are personal to me. But what I find to be really exciting is how Deragh takes the family history and the things that I present to her so seriously. It’s such a beautiful thing. I see it as a gift. I remember when Deragh and Marius Sibiga—the actor who plays the translator—came in and I had made this document of different of people that my great-grandmother had mentioned in these letters and different ideas that I had and they were both referencing them and I was so unbelievably touched by how much they care and how much they bring to the table. And as far as Deragh is concerned, as an actor she’s just so incredibly sensitive and open that—and has good taste, too, so there’s never been a moment when I’ve been like, “That’s not right,” or whatever. The performance has always come to her so naturally and I think that’s a lot of the reason why Never Eat Alone worked, why Veslemøy’s Song worked, because she can insert herself in all these kinds of situations with an open mind and an open heart. It’s true!

DC: I never had an acting teacher but I saw an acting coach once who gave me some advice: that in order to lose self-consciousness in your body and not be stuck in your own head you just really need to focus on the other person, the other performer, or in this case you really need to focus on the material. And so to me that’s the only way you can actually have any pleasure in acting, is if you’re not in your head, if you’re not thinking about what you’re looking like. You actually do have to immerse yourself completely. And I think Sofia is such a nonjudgmental and open director that you don’t have this dialogue with yourself about whether you’re failing or succeeding at giving her what you want. You’re actually able to just focus on what’s in front of you, which I think is why, when I look at Audrey, she actually has way more of my mannerisms than I think any other character I’ve seen me play. And I think it’s because I was so relaxed.

SB: Yeah, I think that really took off in MS Slavic 7, more so than ever.

DC: Yeah, I know, my face just like… moves so much.

SB: Yeah! And also in those monologue scenes it was a challenging situation. We were shooting in Union Restaurant in Toronto. My friend manages the restaurant and he told us it would be completely shut down when we shot, but it wasn’t. He was letting people come in for coffee in the morning because I think people saw that the door was open and he’s such a generous guy that he was like, “Sure, come in for a coffee!” But because we were imposing and not paying we felt rude being like, “Can you stop letting people come in and drink coffee?” And it was really hard for Deragh because it was just the two of us, and she was sitting in this corner, trying to like…

DC: Talk to myself.

SB: Yeah, deliver these monologues and, for me, as someone who’s sitting there directing her I was like, “How do I protect her but also get this scene?” There was no way to put up a wall or get those people out of there, so we just had to do it. But then we saw how it brought this realness and this interesting tension. Because if you were actually doing that in a restaurant by yourself, it would be kind of awkward or difficult.

DC: It was kind of good to have distractions. Sometimes it looks like Audrey is frustrated about what she’s talking about but it’s just frustration from the sound of an espresso machine. [Laughs]

SB: But it worked with the trajectory of the film because we were open to the variables and we let it happen.

Was the manner in which Audrey delivers these monologues, where she’s talking to herself while looking off screen, written into the script?

SB: Some things were part of the original concept and some were found in editing. The monologues being shot that way were part of the original, proposed idea. That was all Deragh in this three-day, three-shot thing, all shot from the same angle.

DC: Yep. And for me, the monologues, or at least the original conception of the monologues, was a way of making visible—or I guess in this case making audible—Audrey’s thought process. I think of it almost as her notes being read aloud, which is why she has the notebook open in front of her. But then things like the subtitles appearing in the first archive scene, or the excerpts of the translations appearing in the third archive scene, these were things that we discovered along the way. We had amazing note sessions with some Toronto filmmaking friends. Those archive scenes were originally going to be silent—there was going to be no information. And people said to us that the story in the letters is so interesting that we have to find a way to represent the words more throughout, because otherwise you weren’t going to know the narrative in the letters at all until the recital in the bed at the end of the film. So we needed to find a device to make the narrative more present. For a while we thought about doing a voiceover…

SB: We tried! We got someone to do a Polish voiceover, but it didn’t work. She sounded like the voice of God, or like the voice of my great-grandmother who is still around. [Laughs] It was too cheesy.

DC: It was cheesy and once the subtitles were included it was even worse, because they’re out of sync with what Audrey’s doing. It’s supposed to be almost like the letters are speaking for themselves. I think that’s a nice way to represent the presence of both Zofia and Audrey.

SB: Yeah, like the weight or the history is there, but you’re not fully absorbing it. It’s around, it’s in the air, but it’s not something that you’re fully understanding yet. Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster does that in her films. She shoots a lot of things where she goes to certain spaces and she tells stories with subtitles and I really like that. Her films were the first I saw that used subtitles that way. So this was another way of doing that. I like the idea of the subtitles being the presence of this character’s great-grandmother, whose essence is around, but she isn’t fully open and isn’t fully connecting to her yet.

DC: Yeah, the desire to understand but not being able to. I think to me the tragedy of anything is knowing that information is there and that understanding is possible but not being quite able to get at it.

Sofia, can you talk a little about your work’s relationship with nonfiction? Of course we talked about the anniversary party and how that grew out of real life. But as far as drawing upon your family history, do you consider how you apply this history as strictly fictional, or is it something in between, or maybe something else entirely?

SB: That’s a great question. I think there’s a lot of truth in this character and the situation that I’ve crafted. But for me it definitely is fiction. There are lots of autobiography in there. When I first wanted to be a filmmaker I didn’t really know where my starting place would be. I tried to make a film in film school and it was awful, just terrible. I really wanted to make work that meant something to me, that was personal, that came of me, and that came through reading my great-grandmother’s work. Like I mentioned, my first short film, Dundas Street—which I co-directed with a friend of mine, Joanna Durkalec—was based on one of her poems, and for the first time I felt like I had something profound to say or to explore. But it wasn’t easy to get there.

Someone asked me in a Q&A the other day if I resented my parents’ generation and why I wanted to explore my grandparents’ history. I think it was just this really natural thing where my parents’ parents, they suffered trauma from the war, and they wanted their kids to have solid jobs. For my Polish grandmother on my dad’s side, all she ever wanted was for us to sit down, to eat food, to know who my best friend at school was and what my favorite topic was—that kind of stuff. She just wanted to make sure that everyone was fed and clothed and okay, and I think as a result my parents, who had artistic inclinations, got very formal jobs as teachers, as well as secondary jobs. My parents wanted that same kind of stability for me because that’s how they were taught. And there’s nothing wrong with that. I don’t resent my parents but they were always like, “If you want to be a filmmaker, it’s probably best if that’s a hobby.” Meaning, you know, that I should get a real job, something that pays well. It doesn’t come out of a place where they think I can’t or that I shouldn’t be an artist, or that they don’t think I’m a person of worth or that I don’t have something to say. It comes from a place where I think they want to protect me, and I think that makes it really hard. Because you want your parents to approve of what you’re doing. You want your family to approve of what you’re setting out to do in life, you want that stamp of approval.

But I think that based on everyone’s history, the way that you’re supported might not be the way you want to be supported. For me to find my voice as a filmmaker, and to be able to find what interests me, I’m very lucky that I have a really interesting family history to draw on, a history that offers me ways to explore and talk about the past. And I think that this film was a way of talking about how family history and ancestry can really impact who you are today without you even realizing it.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.