Interview: Roberto Minervini

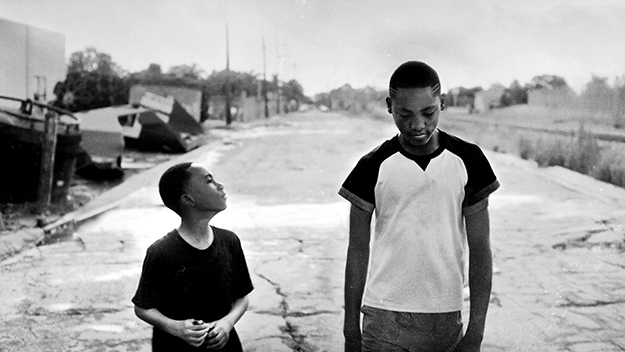

Images from What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? (Roberto Minervini, 2018)

The title of Roberto Minervini’s documentary refers to a 19th-century spiritual, but might as well have been spoken aloud by his resilient Louisiana and Mississippi subjects. What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? looks partly at two young brothers and at steadfast members of the New Black Panther Party as they canvass and protest, but its central, inspiring, and heart-wrenching personality has to be Judy Hill. She’s the proprietor of a bar that may go under, tough-love listener to many, and a survivor herself of so much, as we learn.

Outspoken yet also strong enough to be vulnerable in her openness, Hill has experienced the ravages of drug addiction and yet still draws upon reserves of strength to comfort others. As shown most recently by The Other Side (2015), Minervini has a particular talent for reaching the full emotional depths of the people he meets and brings before the camera, and Hill is no exception, commanding the screen whether holding forth behind the bar or baring her soul to commiserate with a stranger mired in the life. You could call the candor he elicits confessional in its forthrightness and sense of unburdening, if the term didn’t imply in turn a voyeurism that isn’t the case.

Minervini films Hill at home with her mother, at work with friends, and around town, in high-contrast black-and-white that attaches both a raw immediacy and a stringent beauty to the images. Part of the skill to his portraiture here is that no one turns into a generalized emblem for greater experience, even as hard truths about race, poverty, and the steep challenge (and cost) of political change all emerge. Not as dramatic in structure as the bifurcated The Other Side, the film’s triptych spans innocence and experience, with the renewed efforts of the Panthers toward justice amounting to a laboratory for theory and practice (whether going door-to-door raising awareness, or holding the line in protests over police killings).

Fashioned out of the long takes resulting from generally keeping the digital camera rolling, What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? acknowledges the performance inherent to human existence, whether it’s Hill’s striving to stay afloat and put on a brave face, or the children’s learning how to face the perceptions that lurk in the world at large, or the alternately radical and conventional activism of the Panthers. Instead of fashioning these experiences into pat dramas, Minervini collapses the distance between the audience and the people who appear on screen.

The film finally hits theaters on August 16. Eric Hynes sat down with Minervini at the Toronto International Film Festival last year to discuss the film and the director’s remarkable ability to bring hard truths to the screen.—Nicolas Rapold

How did you decide on this story and how did you find the characters that are featured in the film? You say that recent events in American history, such as particularly gruesome police shootings and the general climate of fear in the States inspired you.

It was a difficult time in America, especially in the South. I decided to go into uncharted territories—African-American territories in the South. So I went to New Orleans first, which is just a five hour drive from Houston, Texas, which is where I live. I was searching for people to talk to, really, that’s the starting point. It’s the way that I approach new projects: I start meeting people, and then those people lead me to others, into their world, opening the door to other communities. And that’s exactly what happened with this film. It took me a few months until I found Judy’s bar, and I started hanging out there until I met her. She was the catalyst, the one who introduced me to all the others. The kids in the film—their uncle lives in the apartment above the bar. And Judy is a Mardi Gras Queen. So that’s how it began. It took me around eight months to realize that I should work with her. At first I was just focused on meeting people and I started filming them equally, in terms of time, until I realized that Judy was emerging as a character. I’ve previously discussed the reason why I thought that was the right moment to do a film on Americans of color, and it was very difficult, for me, especially to establish trust. It’s something that is established at a human level and so it transcends everything else, even issues related to politics, race, class. For me, to confront myself as a white European with the reality that I was witnessing, there was a constant rebound effect, a regurgitation of my own condition and beliefs, of my stereotypes about Black America that were crushed.

I would like to ask you about the cinematography—as far as I understand, you were manning the camera from time to time. What was the process of shooting for this project like?

I always use one camera, one lens, and it’s hand-held for ease of usage and movement. There are two operators, me and Diego, we never use cuts so we just pass the camera between each other’s shoulders. The approach is the same for all my films. Not having any cuts is very important to me. Usually when I begin to shoot, I expect a performance to begin, and since I shoot a lot of faces—especially in this film, where there are a lot of close-ups—it’s important to have an uninterrupted shot.

Since you mentioned being in a process of challenging your own beliefs and prejudices throughout, how did this impact the shooting and editing phase?

Considering the long shots and close-ups, in the editing phase—well, what I do is, I never review the footage, not one single shot. That would inevitably affect me and I would start building a story in my mind, and I don’t want that, because then I would start to try to manipulate the organic flow that was in front of me, to fictionalize it, and all that. I have to be very careful and aware of the fact that I am there, that I am very dangerous, that I could ruin everything. So the more I sabotage myself, the better it is for the film. And I have a bad memory, anyway, but which is great in this sense.

But that’s what I do. I don’t review the footage and I give everything to the editor, Marie-Helene Dozo, who is a very good friend, I worked with her on all my films throughout my career. She works alone for some months, editing without any sort of guidance from me. Sometimes I can’t resist the temptation to send her an e-mail in which I say that I see a story in a certain part, but she, she knows me very well so she doesn’t even pay attention to those. She builds her own stories, and since she watches the footage before I do, she sort of can do whatever kind of outline she wants to, sequences in the timeline. Then we get together, for three to five months, and she stays at my house in Houston while we work. We don’t use studios to have a convivial approach, and since Marie-Helene is European and has never lived in the US, this is where things get a bit complicated.

The film holds a mirror to many prejudices and preconceived notions, opinions about the people we see. So, editing it, we try to fight against that. It’s a very deep and cathartic conversation that we have about these issues. But, again, this is not about avoiding prejudice; there is no way of escaping myself. It’s about presenting a work that is the product of a collaboration with the characters and my own learning process, a very experiential process about people, places, their issues and lives. It’s a middle-of-the-road picture presented by a white guy who is learning about the struggle of black America. It’s my own take, rather, my own experience. So we focused on that—giving the audience a feeling of what my experience has been.

What Are You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire is certainly your most political film. However, all of your films are set in the South of the United States, set in Texas and Louisiana. What attracts you to these spaces, to stories of people who live in these areas?

The first four films are tied to each-other, linked, even in the sense of community ties—because there are real life links between the characters. The Other Side (2015), my previous film, was linked to the films of the Texas Trilogy through the figure of the bull rider’s sister. This one [What Are You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire] is a complete departure from my comfort zone, which is people in places that I’m already familiar with. It’s me venturing off into uncharted territories. Since I was attempting to make a film—I didn’t yet know if I was going to succeed—I intended to film African-Americans and their struggles, but I didn’t want to film the ghettos from Houston, that I already knew. I wanted to make a leap, relocate into a context with no safety net, running away from the comfort of my sofa and my house and the feeling of familiarity. I needed all of this to dissolve and to feel completely unfamiliar, so that I could be completely open to a new experience. Vulnerable, scared, a heightened sense of presence and open to listening. Things seem unattainable and unmanageable from there, which I think is a really good place to be. That’s why I ended up in New Orleans, which a very difficult place to navigate if you’re outside the French Quarter. Places one doesn’t usually go to, especially not at night.

That was the only way of doing it—to feed off that fear, to keep it alive, to always stay uncomfortable, so that I’m present, to have a heightened perception and be open. If I get comfortable, then I feel confident and so I’m no longer that attentive. Maybe it’s the human condition, so I try to go the other way around.

In your films, especially in the preceding films, I found an intimate portrait of people who are generally marginalized in society—ex-convicts, drug users, ultra-religious people. People who are generally caricatured, especially in urban, (upper) middle-class circles. You take these sketches and you fill them in, you give them dimension. Is this a conscious part of your approach?

Yes. There are many things to say—I don’t want to sound pedantic, but maybe we need to be careful and rephrase the labels that we use to talk about people, like “minority” or “underbelly.” I also use these words, because Hollywood is so capable of making films about the true statistic minority, which is the one percent, the wealthy, and to normalize that image. Many people think that is America, through these films—but that’s the America of the rich. Numerically speaking, the “underbelly”—those are tens, tens of millions of people. So, when you’re stereotyping them, you’re talking about 40 million people. The magnitude of those who are disenfranchised, of those who struggle, is so big and impactful that I feel it’s my duty to go and shed some light on it, since, as a filmgoer, I don’t see a lot of this stuff, so I want to contribute.

And the other reason is, I come from a blue-collar background and I like to get acquainted and in touch with people whose knowledge is generally empirical. Life taught them some stuff. That’s how I get comfortable. The course of this job, which pushes you to be intellectually performative, it tires me. I had to study really hard to be here, and it’s a lot of work, conscious work that is not one bit spontaneous. For me, to finally just be with people and relate at a different level, and learn from them on top of it, it’s really what I want. I have an affinity for people, for learning from them, things from their own experience. Which is a beautiful thing—they learned it on their own skin and didn’t read it anywhere.

And that’s why, when I got there, I got immediately involved with a bull rider, hence the bull riding scenes. And I never jumped on a bull—no way!—but it was fascinating. I don’t know how to shoot. I don’t have a gun. But somebody teaching me what it means across two hours, in a Texas forest, with animals around you making noises and pointing flashlights at them… my sofa is much better (I keep on going back to this Freudian sofa!), but there is something very primordial in it, which is a part of me and that I miss. I know it sounds a little romantic, but it’s true, though. I would go insane if I just lived in this performative realm, I would lose my mind. What cinema has done to me, has pushed me to become is a performer. And I can’t sustain living in the performance realm. So I’m really drawn to people and when that happens I take the hat off, let the book out of my hand, and get down to something else. And that’s sanity, to me. Or, at the least the combination of these two is sanity.

There is a sensation of closeness that permeates your body of work—which you achieve by visual means, by always being very close to the characters, but also by portraying very intimate moments in your characters’ lives—sex scenes, meaningful discussions, Kammerspiel-like moments. How do you gain this close access?

I take things step by step, but I never really plan on something else, like being distant. It was really not a choice. I’d rather see a project or a particular relationship die out than step back and change the way I want to work. The positive outcomes of the films worked out just fine for both sides. The people engaged with me and the closeness and felt nurtured, protected—and I felt the same way. A lot of the stories in these four or five films are sustained invisibly by stories that are not featured, because they were failures. I wasn’t able to sustain that closeness, that intimacy, or they didn’t want to have me there anymore. Many reasons.

But for me it has never really been an option. There has never been an alternative strategy, or aesthetics, I never even though of that. And now it’s become something familiar. I couldn’t function in a film otherwise. Even as a human being, I wouldn’t be able to function without being very open and close. It would be something that would drive me insane. I’m drawn to people even if I don’t need that, and for me that’s the beginning of a loving and functional relationship.

That’s pretty much why I do it—how, I don’t know. If I’m working on a film right now and already talked about this, I would probably find someone who is willing to try, to go through this with me and then I would get close with the camera. And that’s how I achieve it. There’s no secret to it—except the fact that I truly believe in what I am saying, and I care. The films are a testament to what I do and how I do it.

There is an interesting tendency in your body of films—you started out with fiction films, which are of course inspired by Neo-realistic, Bazinian values, such as nonprofessional actors who are tied to the locations where the films are shot. And as time goes by, you shake off the fictional and achieve a pure documentary form. Usually it goes the other way around, with many filmmakers.

It’s not conscious—I was talking to a friend of mine about the importance of not forgetting. Whatever I do is in the context of an art form, a context of expression. And as an artist, I want to choose new forms of expressing, communicating stories, new aesthetics and approaches. In the beginning, I didn’t set off to emulate a style—not even the Neo-realists, even though I admire them, I would rather say I come from an experimental background. I was working on screenplays and, on the road, I met people and I was drawn to them, and I felt that their stories were way better than what I had written. So I just started fearfully ditching parts of the script and letting their stories come in instead.

That progressed from one project to another, I gained experience until I got courage and, for my third film [Stop the Pounding Heart, 2013], I didn’t write anything. And I went through that and it was hell. It was awful. I cried every other day because I thought I didn’t know how to do anything, or how to finish it. It was like a tantrum, but then after these crises I understood that I’m onto something. Fear and innovation go hand in hand.

Now I’m already thinking on how to continue, to be honest, because after this film I want to continue exploring new forms of telling similar stories. I’m drawn to people and to real story, but not only to this. I haven’t changed the way I shoot, except the camera movements. There’s a need for me to remind myself that I am also trying to be an artist too, which is a thing that something I forget sometimes. I don’t know where this will lead me to—I need to reflect on where I want to go to, but again, I feel scared, like, “What am I going to do?” If I make fiction then boom, people will be like “What happened to the great documentarian?” So yes, I’m scared, but if I’m scared, again, maybe I’m onto something. I’m terrified of fiction, I’m sweating while I’m saying this, and so maybe it’s time for me to do it. Fear is a good thing.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and curator of film at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.