Deep Focus: Daniel Isn’t Real

Images from Daniel Isn’t Real (Adam Egypt Mortimer, 2019)

Daniel Isn’t Real, director Adam Egypt Mortimer’s febrile, erratic phantasmagoria, centers on a troubled college freshman named Luke Nightingale (Miles Robbins), his schizophrenic mother, Claire (Mary Stuart Masterson), and his fear that he’s turning out to be as delusional as his mom. The issue hinges on the title character: his imaginary friend turned fiend (Patrick Schwarzenegger). In the prologue, Luke is five years old (and played by Griffin Robert Faulkner) when a madman rampages through a neighboring café shooting a rifle. The equally young Daniel (Nathan Reid) pops up next to Luke as he stares at the killer’s blood-spattered corpse. Claire, her illness managed, can’t see Daniel—only Luke can. But she’s glad Luke has a buddy in make-believe—that is, until Daniel grinds her meds together and almost kills her with an overdose. She orders Luke to lock him up in his grandmother’s waist-high Victorian dollhouse, then drapes it with a blanket. Fifteen years later, Claire veers into a downward spiral and campus life freaks Luke out. His post-Freudian psychotherapist, Dr. Braun (Chukwudi Iwuj), advises him to unleash his imagination to counter late adolescent anxieties. So Luke frees Daniel. What’s a near matricide between friends?

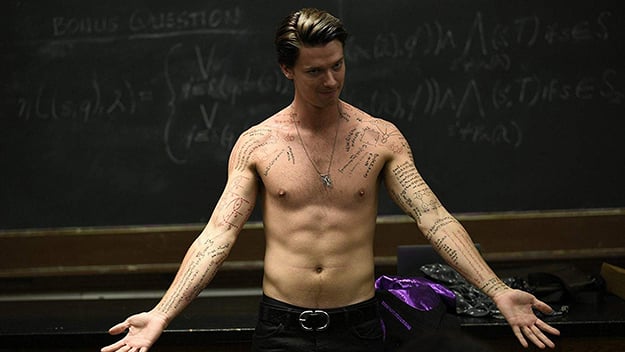

Cowritten by Mortimer and Brian De Leeuw, the movie takes its central conflicts from De Leeuw’s 2009 novel, In This Way I was Saved. We think we’re watching a Jekyll-and-Hyde case stripped of chemical potions. Shaggy, woebegone Luke welcomes Daniel back as a hip know-it-all with slicked-back hair who can help him surmount any obstacle. Daniel seems to be totally on Team Luke. When Luke struggles over equations during a test in logic class, Daniel peels off his shirt to reveal the answers tattooed on his body. After all, Luke alone can see him. Socially, Daniel serves as Luke’s invisible wingman, propelling him past his shyness and insecurity with women. Soon, though, Luke recoils at Daniel’s sadistic manipulations and perversity, especially after Daniel pushes him into a sexual relationship with campus hipster Sophie (Hanna Marks), despite his true love for bohemian artist Cassie (Sasha Lane). The movie turns into Luke Agonistes. As Daniel makes outrageous demands that draw Luke into mayhem, Luke worries that Daniel represents the vicious side of his own true self.

What connects us to the movie is curiosity rather than suspense. Mortimer injects escalating shock effects into the intriguing notion that schizoid personalities could be victims of paranormal parasites. As Mortimer enlarges the context with visions of a galactic vortex and a skeletal incubus with a rake growing out of his head, we suspect that Daniel Isn’t Real will become a tale of demonic possession. We wonder: Is Luke the host for an evil “shadow” archetype? At its most likable, this film is very Jung at heart.

When Luke and Daniel first go to Cassie’s studio, her conceptual art is laughable, but her traditional portrait of her dad shows promise. First-time director Mortimer has the opposite talents. His concepts are more involving than the flesh-and-bone scenes. The movie takes incidents deftly prepared for in the novel, such as a trip into the university’s steam tunnels, overheats them in a garish, often crimson haze, then disposes of them, sloppily. Daniel beats up Luke’s lunkish roommate and singes the philistine’s face on the tunnels’ scalding pipes. But we don’t learn whether Luke gets threatened with expulsion or indicted for assault. (The novel uses the steam tunnels as the setting for a jolting homicide.) Mortimer fails to establish any baseline reality. The action turns increasingly fantasia-like. The movie wants to be a smart, scary thrill-ride but never gets on track emotionally.

DeLeeuw tells the book à la Patricia Highsmith, from the sociopathic shape-changer’s point of view. In the movie, DeLeeuw and Mortimer generally opt for Luke’s perspective. But without Daniel egging him on, he’s got zero personality. We overhear a photography teacher say that what’s crucial to a photo is the relationship between the shooter and the subject. Luke later explains to Daniel that he’s taken up this craft as a way to get to know people. We can’t share in Luke’s deepening empathy when all the director gives us is audiovisual motifs.

The script speckles the narrative with micro-themes that Mortimer drops into the action as if with a pipette. He hopes they’ll lend color and fiber to his melodramatic personae. But they feel second- or third-hand. The movie’s allusions to everything from William Blake’s poetry to Fight Club grow tiresome. At one point, Cassie and Luke (and Daniel) romp through a bookstore after hours, flipping through favorite volumes while recalling passages from memory. Some are too blunt, as with Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. Others are pretentious, like this passage from John Berger’s Ways of Seeing: “To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognized for oneself.” This is an awfully high-toned observation for a lowdown film about a gory, cosmic kind of identity theft.

Mortimer’s visual eclecticism does keep things lively. His team comes up with unsettling face-melding effects. And he pulls off the story’s high point of Grand Guignol: Daniel’s literal invasion of Luke, starting with him stretching Luke’s jaws “as wide as they would go.” At times, Mortimer recalls Guillermo Del Toro, not merely in his Boschian grotesquerie, but also in his skill at reviving antique horror tropes. The dollhouse windows flash with eerie conniptions of color.

Jagged dramaturgy and hyperactive montages in the manner of Darren Aronofsky (Pi, Requiem for a Dream) unfortunately undercut most of his actors. Masterson can be touching as Claire, but Schwarzenegger parodies connoisseurish cool as Daniel. He merges face and posture into one giant smirk. As Luke, Robbins intersperses self-consciously sensitive, inchoate emotions with sweating panic and the occasional malevolent grin after Daniel takes him over. As Cassie, Lane at least conveys Mortimer’s notion that identity crises are an essential part of teenage or twenty-something life. She asks Luke, “Do you ever feel like you have no idea of who you really are?” The problem is, the audience doesn’t know who he really is, either.

The movie is at its most assured and entertaining when it welcomes Dr. Braun into the ranks of cinema shrinks who doubt the power of their patients’ demons. Iwuji delivers a witty portrait of a man too confident and urbane for his own good. He dives into Exorcist-like activity with a Tibetan singing bowl that can bring “clarity to the mind,” and a dagger that can “pierce illusions”—as long as the illusions don’t strike first. Braun underestimates Luke’s inner wild child. When Braun carries his exotic tools in his doctor’s kit on a haunted-house call, it’s as if he’s bringing a knife to a psychic gunfight.

Braun boasts that he looks beyond Western medicine for solutions to mental problems. At that moment we know he’s as doomed as the shrink in Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People who calls the title creatures products of an “overworked imagination.” Whenever Iwuji is onscreen, Daniel Isn’t Real allows us to savor classic horror-movie hubris.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.