Deep Focus: Bleak Street

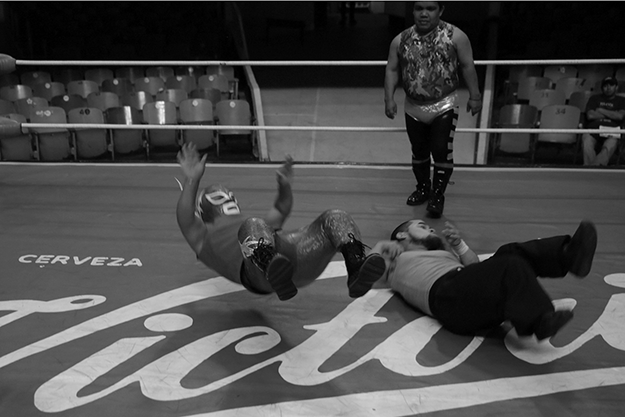

Set in Mexico City’s lowest depths, where sun gets strained through frayed awnings and ramshackle staircases, Arturo Ripstein’s Bleak Street is the grimiest kitchen-sink movie imaginable. Most of the characters live without kitchens or sinks, and they wash up in basins by the street or with communal rooftop taps near a tenement’s water pipes. What’s supposed to give the film a magnetic charge is the real-life mayhem at its core. Ripstein details the events leading up to the accidental killing of two little-people wrestlers—“mini-luchadores”—by a couple of prostitutes in a rent-by-the-hour hotel. Bleak Street is a true crime movie: the double murder occurred in 2009 and was reported across the world. (“Two midget wrestlers died after a drink-fuelled night with hookers,” proclaimed Rupert Murdoch’s Sun.)

This movie depends on your prior knowledge of the ending. Unless you realize going in that the sex workers kill the wrestlers with an overdose of knockout drops (eyedrops that they mix into drinks), there’s nothing to hold you in your seat. True crime films like this one promise to teach you exactly how some violent or scandalous calamity went down. But Bleak Street’s disclosures are not shocking or revealing enough to carry a full-length movie. (They were covered in an episode of Tabloid With Jerry Springer.) Ripstein and his screenwriter (and wife) Paz Alicia Garciadiego package a cavalcade of stunted lives with flimsy evocations of underclass desperation and doom-tinged fate.

Bleak Street arrives on these shores with art-house fanfare. In his six-decade career, Ripstein has been called the most influential Mexican director of all time and an heir to the psychological boldness and absurdist truth-telling of Luis Buñuel. (Ripstein assisted, uncredited, on Buñuel’s 1962 The Exterminating Angel.) But his self-conscious craftsmanship in Bleak Street is the opposite of Buñuel’s fleet, trenchant style. Ripstein wraps up his tough love for marginalized people in overwrought irony and chiaroscuro. It’s too slow and oddly picturesque—the illegitimate child of Edward Hopper’s lonely cityscapes and German expressionism. Even the most public places seem under-populated while solitary spots look as stark as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.

Ripstein’s North American popularity has been tied to the true crime genre. His biggest previous hit was a remake of the American fact-based cult film The Honeymoon Killers (69), Deep Crimson (96), which won a rave from Roger Ebert and is still available on Hulu. But it pales by comparison with the original. What makes The Honeymoon Killers a bizarre classic is the way its one-time director, Leonard Kastle, stumbles into the filmmaking equivalent of tabloid narrative. Watching it doesn’t remind you of other movies, but of thumbing through police-blotter magazines at old city newsstands. Kastle wants everything to be equally factual and titillating: the high-pitched naturalistic acting, the “unblinking” black-and-white visuals, and the straight-ahead progression of the plot, from obese, lovelorn nurse Martha Beck (Shirley Stoler) getting her claws into slick yet needy con-man Ray Fernandez (Tony Lo Bianco) to the clumsy, grotesque murders of her fellow lonely-hearts club correspondents. When the Criterion Collection released the film on DVD, the cover art mimicked the back pages of pulps and big city tabloids, with ads for cheap loans, private-eye certifications, and mail-order diplomas surrounding the title and description of the movie. The design brings back the combination of excitement and fear that lurid murder tales evoked in Fifties/Sixties suburban kids (like me). The movie makes that era’s split between urban and suburban America explicit: it veers into its most ominous deadpan turns after “Latin from Manhattan” Fernandez buys Beck her dream house and they invade the suburbia of Valley Stream, Long Island.

When Ripstein takes on the Beck-Fernandez story in Deep Crimson, it connects to none of those authentic associations, because he smothers it in pseudo art. He shoots his warped romance in a dried-blood, carmine palette, with the tone of black-comic opera. The compulsive over-eater anti-heroine becomes a parody of grand passion as she and her lover splice their fates in killings instead of arias. Confidently made, Deep Crimson has found a sizable U.S. audience. But apart from a factual subplot or two that Kastle didn’t include (like Beck being so crazy for Fernandez that she gives up her two children) and an increased focus on Fernandez’s machismo and hairpiece fetish, Ripstein uncovers little new in the atrocity-streaked story. It feels like a distant replay. Transplanted from its native culture, the tawdry tale loses resonance and gains only an exotic, extremist curiosity value.

In Bleak Street, Ripstein returns to true crime in a more austere form. He injects his chronicle of wrestlers and hookers in a-day-or-two-in-the-life formula. We meet the twin wrestlers, “Little Death” (Juan Francisco Longoria) and “Little AK” (Guillermo Lopez), as they leave their respective wives and baby daughters on the morning of a fight and head to their mother’s house for her blessing. As Little Death and Little AK, they are not just wrestlers in their own right, but also the mascots or shadows of full-size wrestlers who are also called, of course, Death and AK. Outside of the ring, Little Death and Little AK are the only little people in their family circle. The wrestlers view themselves as “Lilliputian gladiators.” They harmonize with the hookers on a bawdy ditty about “midgets” without self-consciousness and with ribald glee.

Their profession completely defines these mini-luchadores. They are afflicted with bullying machismo and a kinky identical-twin closeness that extends to sexual foursomes. (Little Death repeatedly beats his wife, and veteran sex workers raise eyebrows at their dual bedroom antics.) Little Death and Little AK never remove their demonic Mexican wrestling masks, not even at home. Their father is their manager, though he’s too drunk to follow through on basic tasks, like giving Death the proper wrestling gloves. Their mother venerates but also exploits them by controlling their purse strings. After she blesses them again at dinner, she gives them just enough money to pay a couple of aging prostitutes for a party. When the whores drug and fleece them, the women can’t believe what a small bounty these guys won in the ring.

Ripstein’s vision of fate is a pulp cliché; he sees it as a prism of cascading coincidences. When the wrestlers’ mother declares that her twins will always be together, she helps seal their destiny. So do the old hookers when they partner up and decide to brush off their knockout-drug scam just when the two mini-luchadores go looking for a good time.

At times, Ripstein appears to be playing a guessing game with the audience—how low do you think this story can go? The prostitutes lead lives that are far more constricted than the grapplers’. Adela (Patricia Reyes Spindola), who tattooed a sexy angel on her haunch in order to appear hip and youthful, must still give up her street corner to a younger woman. And she supplements her increasingly skimpy streetwalking with panhandling. Her partner in mendicancy is an ancient, immobile, and insensible roommate who might be her mother, but Adela just calls her “the old woman” as she lashes her to a wooden cart. Adela’s friend, Dora (Nora Velazquez), carries her own bag of woes. Her ungrateful teenage daughter Jezebel (Greta Cervantes) embraces a boy on the roof, while her cross-dressing husband Max (Alejandro Suarez) bends her own work clothes out of shape while cheating with a man.

There’s nothing light or playful about Ripstein’s sensibility. He adopts a static, tableau style. It’s as if he wants audiences to take a prolonged look at relationships that, unfortunately, don’t grow any more profound the longer you observe them. Adela says she can’t afford diapers for the old woman and jokes that going commando is healthy for aeration; she periodically blinds the old woman by covering her head in rags. Yet Adela also embraces her from behind, recalling the servant comforting the cancer-ridden woman in the key image from Bergman’s Cries and Whispers. Sadly, you can’t tell whether this striking image is homage or parody.

In passing, Ripstein conveys how difficult it can be for the Lilliputian gladiators and their larger partners to work together. Little AK tells Little Death to stand up to Death as an equal. But Death and AK feel that the little wrestlers are the ones with an advantage: the mini-luchadores know that they move audiences, precisely because they are diminutive. Even the richest sidelight gets caught in Ripstein’s heavy narrative machinery. His dramatic method is to declare an idea in explicit dialogue, then confirm it in action a half-hour later. So at the climax, a pharmacy worker comes forward to identify the hookers who bought the lethal eye-drops because the wrestlers moved her. They were, she tells a cop, so small.

You could write a PhD thesis—and someone, somewhere, probably is—on Ripstein’s use of mirror images. Not only do Little Death and Little AK reflect their bigger namesakes, they are also always checking out themselves in mirrors. Their personae give them firmer identities than anyone else in their picture; we see the others crumble in reflections. The wrestlers’ grief-stricken mother disintegrates as she reaches for a snapshot of her boys that’s tucked into a wardrobe mirror, and we witness the humiliation of Dora wrestling with her lingerie-snatching husband via the floor mirror in her cramped apartment.

These shots made through a glass darkly, like the movie’s entire, oracular visual idiom, provide only an illusion of meaning or poetry or depth. The director comes off as habit-bound or fatigued as his characters. So Bleak Street ends up mostly just reflections in a bloodshot eye.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.