Deep Focus: The BFG and Life, Animated

The BFG

Roald Dahl’s big idea for The BFG, as he noted in his “Ideas Book” years earlier, was to explore “the man who captured and kept in bottles—Ideas from the brain—Thoughts—Pieces of knowledge—Jokes—I saw them thrashing around furiously in their jars.” But when Dahl finally got down to writing the book, these captive ideas, thoughts, pieces of knowledge, and jokes turned into dreams. The dream catcher became the Big Friendly Giant, the non-cannibalistic runt in a colony of man-eating giants who roam across the globe at night, looking for juicy “human beans.” In the early 1980s, when Dahl was at the start of a final stretch of genius that produced The Witches and Matilda, the novelist instinctively knew that an idea as ethereal as dream-catching needed primal ballast. So he came up with a surefire hook: the BFG kidnaps a girl named Sophie from an orphanage simply because she looks at him. He’s sure she’ll give away his existence, and that the usual heedless authorities “will be putting me in the zoo with all the jiggyraffes and crocadowndillies.” Once Sophie sees what the BFG is really up to—brightening children’s lives by breathing dreams into their heads at night—the two form a fast friendship. They team up to defeat the monsters that bully the BFG in Giant Country, and even get a lot of help from Her Majesty the Queen.

Dahl recognized that with the wacky effrontery of this setup, his novel could support pages of riffs on children’s dreams—such as, “I HAS A PET BEE THAT MAKES ROCK AND ROLL MUSIK WHEN IT FLIES”—as well as vaudevillian routines on the giants’ favorite tastes in human beans, like the humongous Bloodbottler stating: “I is very fond indeed of English schoolchiddlers. They has a nice inky-booky flavor.” As you can tell from just these quotes, the book is a Lear-y wonder of nonsense talk. “Words is such a twitch-tickling problem for me all my life,” laments the BFG. And why wouldn’t they be? To learn how to read and write, he constantly re-read Nicholas Nickleby (by “Dahl’s Chickens,” aka Charles Dickens). He and his fellow giants talk only in “gobblefunk.“ For readers, this dialect is a joy: “chatbags,” for example, is certainly an improvement over “chatterboxes.” And there’s a wild comical synesthesia to such gobblefunk nouns as “snozzcumber,” the repulsive gourd that is the basis of the BFG’s diet; “frobscottle,” the BFG’s delicious carbonated drink, distinguished by bubbles that fizz downward, not upward; and “whizzpoppers,” the titanic bursts of flatulence that accompany guzzling frobscottle.

Steven Spielberg gets a lot of that humor and invention into his super-deluxe 3-D movie version of The BFG, starring young Ruby Barnhill as Sophie and Mark Rylance in an ace motion-capture performance as the BFG. From the start, the director scales the production to Spielbergian heights: in the book, the orphanage is in a small village, but in the movie it’s in a pop-up book rendition of 1982 London, with a rowdy pub and a wood-paneled bookstore within sight of Sophie’s communal bedroom. Spielberg is at his best in these early scenes. He knows how to keep the action ominous and playful as the spindly giant, carrying an elongated trumpet and an old-fashioned suitcase, leaps mysteriously along the streets at 3 a.m., and, using his dark cloak as camouflage, seems to melt into urban nooks and crannies. The shots of the BFG’s hand approaching Sophie’s bed and snatching her, like the later ones of him extending it in friendship, for protection, recall the scary/lovable hand shots in John Guillermin’s underrated King Kong. When the BFG knots Sophie’s quilt into a hobo bag and hops from one rock tower to another across some unnamed sea and into the wild, the movie brims over with magic and anticipation.

The BFG

Once they enter the BFG’s cave, the movie begins to feel becalmed. The getting-to-know-you scenes are static, uninspired. It seems that Spielberg and his gifted screenwriter, the late Melissa Mathison (Kundun, The Black Stallion), who forged a classic partnership on E.T., are striving to achieve a poignancy that isn’t there and isn’t necessary anyway.

When reading The BFG, we never question why Dahl wrote the book: he communicates his writer-entertainer’s delight in giving a performance. (My own first impression of Dahl came from watching his 1961 TV show, Way Out, a sci-fi/fantasy anthology that briefly preceded The Twilight Zone on CBS. He delivered sardonic introductions on subjects such as the use of ground tiger’s whiskers as a murder weapon.) As Spielberg continually adds shades of E.T. and Elliott, especially Sophie and the BFG touching fingers, we do wonder why he wanted to adapt this book. Dahl’s The BFG is an uninhibited frolic with a pungent subtext about an orphan girl bonding with an oddball surrogate dad. (The final chapter states: “She loved him as she would a father.”) Spielberg turns the subtext into text, then inflates it. We have no problem accepting that Sophie would warm up to the BFG once she knows he is no “cannybully.” He is delightful, and in his own rustic, antic way he does speak beautifully. But the filmmakers keep doling out dollops of sweetness and pathos, which blunt Dahl’s sharp whimsy. When the movie’s BFG reads aloud from Nicholas Nickleby, he chooses this self-loathing passage: “He felt as though the light were a reproach, and shrunk involuntarily from the day as if he were some foul and hideous thing.” Generally, Spielberg packs the frame with so much amusing clutter that he detracts from Rylance’s witty, emotional line readings. The “gobblefunk” is beguiling but our eyes and ears can handle only a fraction of the daffiness. Despite the restrained pace, the result is audiovisual overload.

Dahl’s cheeky sensibility still permeates much of the action, including the byplay among the giants, notably Jemaine Clement as the imposing yet stupid Fleshlumpeater and Bill Hader as Bloodbottler, his cannier sidekick. The film’s mid-section does contain a few startling images, like a sleeping giant suddenly emerging from a blanket of turf that covers him head to toe. But a virtuoso slapstick setpiece of giants toying with full-size cars as if they were Hot Wheels and the BFG a crash mannequin goes on too long and fizzles out. Likewise, our heroes’ journey to Dream Country is gorgeous but prosaic. The dreams fly by in abstract blurs; even the best of them, “the golden phizzwizard,” zips around like a second-hand Tinker Bell. The film doesn’t come fully to life until they reach Buckingham Palace. Here Spielberg’s talents for mocking clichés and choreographing farce rise and shine. Penelope Wilton, as the Queen, Rebecca Hall as her handmaid, and Rafe Spall as her butler are wonderful because they share a style of droll, knowing dignity. (After magnificently playing the sensible, middle-class Isobel Crawley for 52 episodes of Downton Abbey, this time out Wilton revels in being a queen.) Nothing leaves the Queen and her retinue nonplussed, including an epic bout of whizzpopping.

Life, Animated

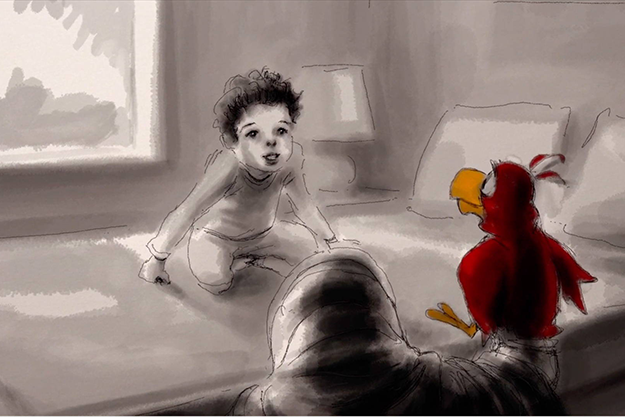

Roger Ross Williams’s documentary Life, Animated, also opening this week, is far more transporting than The BFG. Inspired by Ron Suskind’s book Life, Animated: A Story of Sidekicks, Heroes, and Autism, it’s a clear-eyed chronicle of how Suskind’s younger son, Owen, was diagnosed with autism at age 3, then forged his own understanding of the world and his place in it via immersing himself in traditional, hand-drawn Disney cartoon features. What could have been a case-study movie is as full of surprises and twists as any thriller. It contains heartbreaking, empowering episodes that aren’t in Suskind’s 2014 memoir, since it draws on years of home movies and on Williams’s footage of Owen’s life at age 23, after Suskind wrote that book. Owen, his brother Walt, and his parents, Ron and Cornelia, come into focus as textured, full-bodied characters, doing their imaginative, empathic best while confronting their limits honestly. Remarkably, Owen taught himself to read and to write by watching cartoon credits, and he began to converse with his family and to express his own emotions by using lines he learned memorizing Disney. He scripts his own Disney-like scenario, Land of the Lost Sidekicks, featuring sidekicks from Disney movies, with Owen as their protector. The villain has one key superpower: the ability to fog the sidekicks’ minds. Williams gets the Mac Guff animation house to render it in a broad, colorful, appealingly un-slick style. Though Owen’s achievements are extraordinary, the film demonstrates that there are things Disney cartoons can’t teach: full self-sufficiency and satisfying adult sexual relationships.

In Suskind’s book, he notes that Owen has campaigned to bring back hand-drawn cartoons. Owen doesn’t respond as deeply or as subtly to computer animation. Suskind theorizes that the digital work done at Pixar is less exaggerated and more lifelike than Pinocchio or Dumbo or Aladdin or The Lion King, and thus more challenging for Owen. I’d like to think that Owen’s preference for old-fashioned cartooning derives from something more intangible: the presence of the human hand in the act of creation. (I think it’s something we can feel even in writers who compose their work in longhand, like Dennis Potter and Pauline Kael.)

Throughout The BFG, I kept flashing back to illustrator Quentin Blake’s sprightly, whimsical, cartoon-like drawings and appreciating how they complement Dahl’s nimble prose. To his credit, Spielberg made a point of mixing exquisitely wrought sets and props with virtual reality, but the resulting look is weightier and far less spirited than Blake’s. When Spielberg makes films from the inside out, as he did with E.T., his presence can be intuited in every brushstroke. In a super-production like The BFG, he’s more like a ringmaster/impresario than an artist, and his vaunted “sense of wonder” feels in places like something drawn out of a fraying bag of tricks.

Michael Sragow is a contributing editor to FILM COMMENT and writes its Deep Focus column. He is a member of the National Society of Film Critics and the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. He also curates “The Moviegoer” at the Library of America website.