Cities and Exiles: In the Last Days of the City and Art of the Real x 2

In the Last Days of the City

A film about trying to make a film, Tamer El Said’s In the Last Days of the City (2016) feels at once impressionistic and monumental, a drifting collage of fragments that amounts to something singular and fully realized. As a mesmerizing, turbulent portrait of Cairo on the cusp of the Arab Spring, it gestures toward the “city symphony” genre, which goes back to Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927), Alberto Cavalcanti’s Rien Que Les Heures (Nothing But Time, 1926), and Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929), attempts to capture the texture and soul of a metropolis with a camera. More personal and less celebratory than these jazz age experiments—if also less alienated than Ben Maddow’s The Savage Eye (1960) or Chantal Akerman’s News from Home (1977)—its tone is elegiac, at once tender and frustrated. El Said’s film confronts the impossibility of imposing order on the chaos and noise of a big city or tying up the unraveling strands of a life. Even more piercingly, it expresses the anguish of loving impossible cities: places that batter their inhabitants with war, violence, political or religious oppression, yet keep a hold on them with beauty, memory, an ineffable sense of belonging.

“I don’t know if it’s something I love or I hate,” the young filmmaker Khalid (Khalid Abdalla) says of Cairo. “All I know is I want to film it.” His ambivalence and uncertain yearning suffuse the whole project, which weaves together scenes from Khalid’s life with pieces of his unnamed and unfinished film—fleeting glimpses of street life and snippets of interviews, often shot in such tight close-up that we see only parts of faces. Sometimes it is unclear what we are watching until the scene freezes, speeds up, or repeats, as Khalid and a collaborator edit the footage on a computer. Both the man and his work seem clouded by the same melancholy indecisiveness, and graced by the same vulnerable delicacy. In recurring scenes, the handsome, introverted Khalid visits his dying mother in the hospital, feeding her slices of apple and questioning her about why she covers her hair; he broods about Laila (Laila Samy), a former girlfriend who has decided to leave the country; he prepares to move out of his flat, and in a subplot tinged with mordant humor, visits apartments with a real estate agent. One has chickens roosting in it; one is in a building with an elevator that starts playing recorded Islamic prayers when they enter.

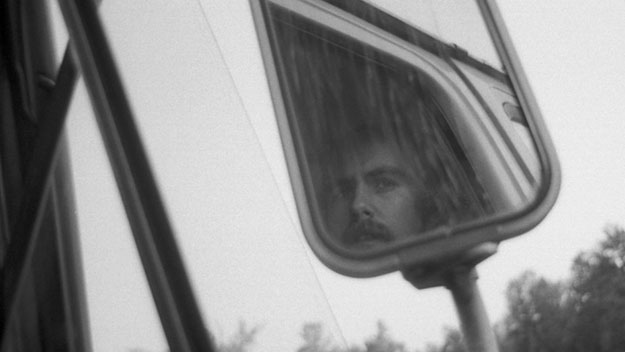

Meanwhile, the protests in Tahrir Square gather strength, with chanting crowds calling for the downfall of Hosni Mubarak. (In the Last Days was shot over the course of 2009 and 2010.) In every taxi cab and café, radios or TVs drone on about Mubarak, about the Africa Cup soccer games, about bombings in Iraq, unrest in Yemen. Khalid seems disconnected from these events, his reactions muted and questionable. He photographs a demonstrator being savagely beaten and hauled away in a truck, and he disturbingly shoots from his window a man attacking a woman, getting the footage rather than intervening. “Watching is not living,” he is warned by one of his interview subjects, an acting teacher, but his frequent positioning near windows frames him as fundamentally an observer.

In the Last Days of the City

A joyful break from this sense of isolation and futility comes with the reunion between Khalid and three visiting filmmaker friends: the Lebanese Bassem (Bassem Fayad, the DP for In the Last Days of the City) and two Iraqis, Hassan (Hayder Helo), who still lives in Baghdad, and Tarek (Basim Hajar), who now lives as a refugee in Berlin. We meet them first at a post-screening panel—where, Bassem points out, the subject is supposed to be cinema but all the talk is about politics. Over the course of the night, the four friends talk at an outdoor café, then on a rooftop above Tahrir Square, where they swig beers surrounded by glowing LED billboards and the thrum of traffic.

Their conversation parses out the film’s deepest concerns, with eloquent speeches rising naturally from a warm, spontaneous flow of affectionate teasing and bickering. The men talk about their cities as friends, as whores, as image machines. Tarek and Hassan argue passionately about leaving versus staying in Baghdad; one calls the city “something I can carry with me,” the other says it is “a moment—you feel it and then it goes. I can’t live outside it.” With poetic intensity and compelling bluntness, they talk about living with war: about a mother sending her child out on an errand and casually instructing her not to step on the dead body; about watching a corpse in a truck dripping blood down the street; about how the constant threat of death makes people appreciate even the simplest actions of everyday life more intensely.

Finally, at daybreak, the four careen through the empty streets in the open back of a truck, aiming a camera up at elegant, ochre-colored, Ottoman-era buildings in the dreamlike haze of dawn. As they part, Khalid’s friends promise to send him footage from their own cities for his film, and these video diaries become another strand in the cinematic braid. Hassan’s images of Baghdad take in rubble and fires and doves and children, an old calligrapher at work and a tranquil view of a river in the old-gold dusk. Bassem recounts stories of his childhood over cool, blue-gray, rain-streaked views of a seaside promenade near Beirut. For once, there is a good reason for the conspicuously hand-held quality of much of the footage—we are meant to be conscious of seeing the world siphoned through the digital eyes of these small, lightweight machines to which the men are so attached.

In the Last Days of the City

The meditative vignettes of Beirut and Baghdad contrast with the overwhelming visual density and constant motion of Cairo: street vendors and beggars and colorful storefronts picked out momentarily from the surging, jostling crowds, all drenched in a syrupy, apricot light. But this boisterous energy and rich sensuality clash with hints of repression and danger. Signs on walls admonish, “Thou shalt not look at women,” but the camera looks very pointedly at a group of voluptuous, naked female mannequins being arranged in a store window. A veiled wife refuses to let Khalid and the agent in to see a prospective apartment because there’s no man at home. On his computer, Khalid watches old footage he shot of Laila, her face filling the screen, a white flower behind her ear. When he asks her what she wants most, she says that she would like to travel, “Because I want to kiss you in the street.” In the vaguely menacing crescendo of crowds—celebrating an Africa Cup victory or protesting the government—there is a sense of pent-up energy on the verge of exploding.

But in the end, the overwhelming impression created by this restless collage is a sense of loss: of homes, lovers, parents, and friends; of identity, safety, and certainty. It is all summed up in gorgeous yet deeply sad sequence of an old building being demolished, walls crashing down and stones crumbling into powder. Workmen stop to look through photographs they’ve found, then rip them up and toss them away. The effort to find cohesion in fragments, to hear silence amid noise, is essential to city life, and perhaps to all modern life. Each image on screen—Hassan’s footage of candles floating in the river, or Laila with a white flower in her hair—is both something salvaged, and a symbol of something lost.

“I don’t know where the film starts and my life ends,” director El Said has said. Though Khalid shares the name of Egyptian-British actor (and co-producer) Khalid Abdalla, he is in many ways a directorial alter ego—his on-screen apartment was El Said’s own. The multi-year struggle to finance and complete In the Last Days of the City mirrors the plight of the film-within-a-film, adding further layers to the confusion between reality and cinema. The New York premiere of In the Last Days of the City coincides with the 2018 edition of Art of the Real, a showcase of “nonfiction and hybrid filmmaking,” and several titles in the series make good companion pieces.

Central Airport THF

In Karim Aïnouz’s exquisite Central Airport THF, refugees from the Middle East live in a surreal limbo in Berlin’s disused Tempelhof airport. The film’s use of wide-screen space and attention to the power of architecture—cavernous, majestic hangars, often framed in extreme long-shots—counterpoint its humane focus on the migrants’ day-to-day experience. It creates an immersive sense of a place that is—like every airport—no place. That the building was erected by Hitler as a symbol of German might is an irony that scarcely needs underlining. The huge, bombastic spaces have been divided up into a warren of white cubicles affording families a modicum of privacy. Everything is spotlessly clean and orderly, and the German and immigrant workers who assist the refugees through a maze of bureaucratic paperwork and medical screenings are unfailingly patient and kind, yet the cold impersonality of the setting, the dislocation and the total idleness to which the inhabitants are reduced, are chilling. Waiting, some for years, to get their “status” so they can leave the airport and restart their lives, these people truly have “nothing but time.”

Central Airport movingly follows Ibrahim, an 18-year-old Syrian boy separated from his family, over the course of a year. He and other characters speak longingly of their homes, their villages, the verbal pictures contrasting starkly with the images on screen—concrete hallways, makeshift bunks, fluorescent-lit cafeterias, young men huddling on benches outside the hangars smoking cigarettes or water pipes. “My memories of home are vanishing more and more,” Ibrahim admits. The heated arguments of In the Last Days of the City between Hassan and Tarek, over risking one’s life to stay in Baghdad or accepting exile in Berlin, make more sense once you see how mercilessly the migrant experience uproots and dispossesses.

Making films as a way to understand the messiness of history, to make sense of displacement and loss, also drives The Image You Missed, Donal Foreman’s cinematic conversation with his late father, whom he hardly knew. Arthur MacCaig was an Irish-American filmmaker who was drawn to Belfast, making a number of documentaries about the Troubles, the violent conflict between Republicans and Loyalists in Northern Ireland. Foreman deploys film and video footage from his father’s archive, along with photographs and letters read in voiceover. While speaking as a son to the father who largely avoided contact with him, he also speaks as a filmmaker to a filmmaker, analyzing the two men’s very different attitudes towards politics, cinema, and Ireland. He concludes, ultimately, that these disagreements have much to do with changing times; his father lived in an era when it was still possible to believe in armed struggle and revolution, and to make films with a clear-cut ideological stance, while Foreman feels this is no longer valid. He includes some footage he shot at the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York, and speaks of his frustration: “There were too many cameras, too many images.”

The Image You Missed

But, as the film’s title suggests, the 21st-century glut of images still leaves us hungry, unsatisfied. (“Cairo has such images,” Bassem marvels in In the Last Days of the City. “No other city has so many images.” But Khalid looks out over the seething city and laments, “There’s something I can’t capture in all this.”) Foreman hunts for elusive glimpses of his father in the archive; at one point he pieces together a montage of photos that takes Arthur from birth to death in a minute, and serves only to accentuate his absence and unknowable-ness. But by watching the films Arthur MacCaig made, we can see what he saw, and what he wanted to show: Belfast as a city, like Beirut or Baghdad, that is not just a headline and a daily body count, but a place where children play in the grey, grim streets, where people shop and ride buses and go about their lives under huge, colorful murals honoring the IRA’s martyrs and cause. For MacCaig and Foreman, as for El Said and his collaborators, the boundaries between the personal and the political are as blurry as those between cinema and reality. Watching may not be living, but for some people, filming is life.

The Image You Missed and Central Airport THF screen as part of Art of the Real at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy, and has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere.