By Vivian Sobchack in the November-December 2014 Issue

Time Passages

Do not go gentle into that good night

Intimate space and exterior space keep encouraging each other, as it were, in their growth . . . It is through their “immensity” that these two kinds of space . . . blend . . . and become identical.

—Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

From the November-December 2014 Issue

Also in this issue

The title of Christopher Nolan’s extraordinarily ambitious science-fiction film Interstellar is three-dimensionally flat and far less descriptive than it should be. Pointing only to exterior space and distant stars, it obscures the film’s more urgent interest in the fourth dimension of time and the foreshortened future of life on our own planet. Outwardly focused only on the immensity of the cosmos, it also ignores the film’s inward focus on the immensity of intimate space as it is lived in intense love and irrevocable loss by an earthly—and time-bound—human family. Finally, given its empirically neutral tone, it conveys nothing of the film’s heart-rending affect and moral gravity, which, “encouraging each other in their growth,” expand individual anxieties about the future of one’s own children into collective responsibility for the future of others. In sum, suggesting just another science-fiction blockbuster set in outer space and full of special effects rather than ideas, the title is an annunciation hardly worthy of the complex multidimensionality of the film itself.

Interstellar, however, is full of ideas as well as wondrous imagery. Indeed, it weaves an intricate fabric of three-dimensional space, fourth-dimensional time, and a cross-dimensional gravity that enfolds—and blends—cosmic and intimate immensity to transform what, in other hands than Nolan’s, would have likely been a comfortably predictable variation of a long-familiar science-fiction plot about our—and our planet’s—impending extinction. Set in the near future, Interstellar’s action is motivated by the exhaustion of an Earth that is rapidly turning into a polluted dust-bowl incapable of sustaining its slowly starving and increasingly ill population. It is then fueled by a decimated NASA’s exploratory and obstacle-filled mission into deep space and through a wormhole that, folding space in on itself, will, it is hoped, also become a “time machine,” making it possible to find a habitable new home planet in an otherwise unreachable distant galaxy. In the crew’s search, there are, of course, increasing complications—both cosmic and human.

Nolan, however, makes this familiar trajectory wonderfully strange and intellectually compelling by imaginatively directing it into and through a wormhole of his own design. Fully aware that cinema is, itself, a time machine, he has expanded—and compounded—the relativity of space-time and its effects by layering them in the multiple dimensions not only of Interstellar’s narrative but also of the film’s overall structure and its immersive mise en scène. Simultaneously, all three play out the tension between “intimate” and “exterior” space-time and, in the film’s moving final third, resolve—by unifying—their different immensities and seemingly incompatible values.

At the narrative level, this resolution occurs in two plot threads—one personal, the other cosmic. Immense in its intensity, the personal thread ultimately reconciles a widowed father, Cooper (Matthew McConaughey), the eventual leader of the interstellar mission, and his earth-bound daughter, Murphy (played at different ages by Mackenzie Foy, Jessica Chastain, and Ellen Burstyn), after a decades-long and emotionally fraught separation in both space and time. Central to the plot, with humanity’s future hanging in the balance, the cosmic thread is also about reconciliation, and the desperate need for a unified theory of quantum gravity. Again accomplished in the film’s last third, this reconciliation occurs not in theory but through experience, and resolves fundamental incompatibilities between Einstein’s geometrical description of the relative structure of space-time and quantum physics’ mathematical description of the particle- and wave-like behavior of both subatomic and macroscopic physical matter.

However, these are not merely parallel narratives in which one thread is substantially unnecessary and subordinated to the other. Here, in contrast to most science-fiction action films, the personal dramas of the main characters do not function merely to humanize—and provide occasional relief from—the genre’s primary emphasis on scientific exposition; a depopulated, if spectacular, outer space; and the technological operations of a completely unrelated mission. As penned by Nolan and his brother Jonathan, both the intimate and the cosmic narrative threads are absolutely essential to each other. Thus, spanning an extraordinary visualization of two varieties of (dare I pun?) “relative” time, the familial reconciliation enables not only the theoretical but also the practical resolution of interstellar space travel—and, quite literally, at the very same time, the actual unity of supposed theoretical incompatibilities allows father and daughter to communicate across what seem incommensurable dimensions of space. Their cosmically distanced yet intimate reunion produces a myriad of possible futures, in one of which they will come together once again.

In this regard, perhaps the spatiotemporal rule most important to Interstellar’s personal narrative is drawn from Einstein’s work on the effects of gravity and mass on the dilation and contraction of time. It has long been recognized that time dilates and “passes” more slowly in the gravitational field of astronomical bodies of greater mass than those with lesser. Thus, before he leaves for outer space, promising his 10-year-old daughter Murphy that he will come back, Cooper tells her: “Time is going to change for us.” For him, “it’s going to move more slowly,” so that when he returns they “may even be the same age.” Later in the film, on a massive planet where every hour equals seven years on Earth, we can feel Cooper’s anguish at the botched heroics of crew member Brand (Anne Hathaway) as he tells her she has cost them all “decades.”

Interstellar’s cosmic narrative also draws its rules from contemporary astrophysics, and particularly the work of theoretical physicist Kip Thorne (credited as one of the film’s executive producers). His research and calculations have primarily addressed the spatiotemporal properties of wormholes, black holes, and relativistic gravity and its “waves,” and their likely effects on physical matter. (Each phenomenon is spectacularly visualized in the film.) Also relevant to the scientific credibility of the narrative’s temporal trajectory and resolution, Thorne’s work suggests that the frequently polarized behavior of quantum fields makes “backward” time travel impossible—and thus disallows not only the completely circular closure of space-time but also the long-popular science-fiction conceit of traveling back in time to alter the past and thus change a catastrophic future. He says nothing specific, however, about whether it is possible to revisit the present—a temporal paradox that has particular significance to both the logic and great poignancy of the film’s final third, which keeps father and daughter apart and yet brings them together across what seems an infinite hall not of mirrors, but of time. However, Thorne has also calculated that the passage of “simple” masses through a wormhole or black hole would make the very notion of temporal paradox meaningless since multiple permutations of time would exist simultaneously and all would be equally possible and true.

Uncharacteristically, but appropriately, Nolan has chosen to contain and clarify these multidimensional scientific puzzles as well as the film’s central but spatially and temporally fractured father-daughter relationship in a classically constructed narrative served by traditional continuity editing. Thus, bracketed between a temporally ambiguous prologue and a heart-breaking yet hopeful epilogue, the film has three acts (as they’re called in the trade). While each advances the plot toward its resolution, all are spatially and temporally different.

The first is completely earthbound and set in the near future—although its mise en scène clearly evokes historical associations with the dust bowl of the Great Depression, it also points to contemporary climate change and the looming threat of similar conditions today. From the beginning, we are immersed in a world that is fully and concretely realized. Nolan, bless him, has chosen once again to shoot on film, build sets rather than use green screen, and employ as little CGI as possible—a tall order for a science-fiction narrative located, in its long second act, in deep space. The result, however, is a rich, textured, and lived-in realism that, by comparison, is lacking in the film’s outer space sequences.

This grounded first act, however, primarily takes place on a deceptively green family farm with neatly sprawling cornfields, where we meet the Cooper family at breakfast, sit in on a parent-teacher conference about the occupational prospects of Cooper’s teenage son and particularly beloved young daughter, watch an azure sky obliterated by a massive dust storm, and learn, through small but surprising “futuristic” details casually placed in an otherwise familiar mise en scène, and in passing dialogue rather than exposition, that there are no longer any scholarships for college or diagnostic MRIs; that NASA and the space program are long gone and discredited, but drones are common; that there is widespread pollution and cancer; and, most significantly; that Earth is running out of food (albeit not engineers and television screens), and mass starvation is literally on the horizon, where black clouds of smoke billow from the burning of the very last crop of okra so as to make way for more corn.

This acceptance of life as usual in the face of an increasingly hostile environment contracts time, foreshortening and eventually foreclosing the possibility of a terrestrial future. Indeed, once an engineer and NASA pilot but now a much-needed farmer, Cooper decries the collective loss of hope and can-do pioneer spirit with tag-line dialogue that has appeared in almost all the film’s trailers: “We used to look up at the sky and wonder at our place in the stars. Now we just look down and worry about our place in the dirt.” However, in a hidden NASA facility, whose rural location has been discovered by Cooper and Murphy under strange circumstances, the tone becomes urgent (if, as often occurs with the genre’s scientists, increasingly didactic). A space mission to find a new home is secretly in the works and planned by astrophysicist Dr. Brown (Michael Caine), who tells Cooper: “We’re not meant to save the world, we’re meant to leave it.” By the first act’s end, to Murphy’s great despair—and anger—at her impending abandonment, her father has been recruited as the mission’s leader.

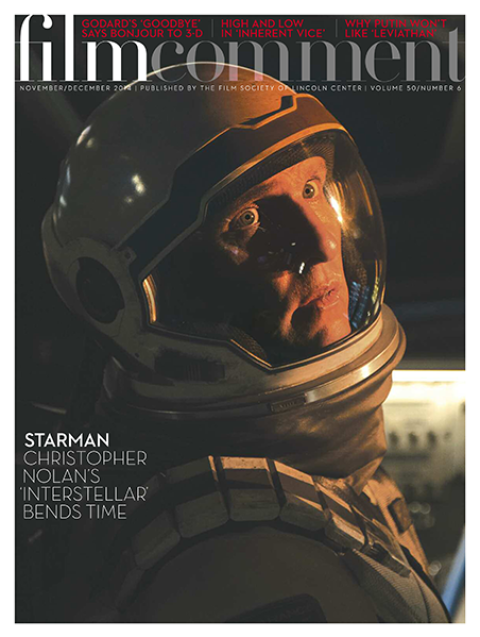

The rich and deep texture of the first act’s world begins to flatten in the NASA facility, where the emphasis is abstractly on the future of the human species rather than affectively, as Cooper would have it, on the human family. The imagery also moves from the concrete grit and dust of hardscrabble human existence to, well, actual concrete, and towering and gleaming rocketry. Unfortunately, this comparative flatness pervades the film’s second act (as well as its title), and certainly has something to do with CGI and a lot to do with our familiarity with narrative and visual science-fiction conventions. Indeed, despite Nolan’s best efforts and good science, it may be easier to find new habitable planets than new things to do in movies set in outer space, and easier to avoid asteroids than generic clichés or references to iconic science-fiction films. Indeed, after mission lift-off, the second act’s first major opportunity for spectacle—the ship’s passage through the wormhole—is thus a dazzlingly kinetic light-show reflected on Cooper’s helmet as our only point of spatial reference, which, not surprisingly, recalls the Star Gate sequence in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (reported to be number one on Nolan’s top 10 list of favorite films).

Since we’ve seen it all already but for small variants (however spectacularly big on screen), the genre’s visual and narrative novelty has become more limited in outer space than if, as Nolan’s first act proves, it had remained on Earth. Thus, however likely to be Interstellar’s biggest attraction, the film’s second act tends to substitute obligatory generic spectacle and action for textural substance and textual depth. However, to Nolan’s great credit, narrative attention keeps returning to Cooper, and to his—and the film’s—awareness of time’s irrevocable passage, whatever its relative elasticity.

As the ship travels toward planets in a distant solar system, time slows as gravitational forces increase. The effects on the crew as well as on those at home are made powerfully and poignantly explicit through a series of video communications transmitted to the crew from Earth. Over a dilated and hence brief period of time on the ship, to a crew that looks much as they did when they boarded, the videos from home show what seem to be rapidly aging loved ones (a grown-up Murphy and her older brother Tom, played here by Casey Affleck), all of whom report on family illnesses, deaths both natural (Cooper’s father-in-law) and cancerous (Cooper’s young grandson), and increasing terrestrial misery.

Nolan also uses parallel editing between Murphy on Earth and Cooper in space to compound this temporal disparity, which becomes even greater when the crew reaches its destination and begins exploration of two potentially habitable planets. As spectacle and action accelerate, Cooper, always thinking of home and his promise to return to Murphy, experiences time’s extraordinary plenitude as a great and terrible loss. Indeed, after barely escaping from an uninhabitable planet of mammoth tidal waves, he calculates with bitter exactitude that the “slightly” delayed stay there lasted, in Earth time, 23 years and 4 months. As the spectacle- and action-packed second act ends, the ship’s communication systems have been severely damaged, and any chance of returning home also seems remote. Desperate to relay their research data and news of a significant discovery back to Earth, the plan is to move closer to a nearby black hole and take advantage of the gravitational waves around it. However, now with little to lose and possibly everything to gain from its mysteries, Cooper separates from the ship in one of its modules and intentionally lets gravity pull it into the black hole.

In contrast to its second act, the third act of Interstellar is strikingly original, narratively mind-bending, and visually stunning. Here the film reaches an emotional and intellectual climax that brings together the disparate dimensions and incompatible temporalities of an earthly home and a distant cosmos. At once separating and yet conjoining intimate space and exterior space is the wall-length bookcase in what was once 10-year-old Murphy’s farmhouse bedroom. Standing there in front of the books years ago, she and Cooper had pondered a set of strange patterns made by the dust on the floor, a message from what she had called a “ghost” that led them to the hidden NASA facility and everything that followed to their present moment. Now a grown woman possibly older than her astronaut father, Murphy is a scientist still working on the unresolved problems of interstellar travel, the solutions to which would ensure the future of her own—and the Earth’s very last—generation.

Visiting the family farm before it is abandoned, and drawn to her old bedroom, on the earthly interior side of the bookcase, Murphy moves among childhood possessions. On the cosmic exterior side of the bookcase is space-suited Cooper. He has first fallen into and now floats in a space-time whose initially abstract geometry has slowly taken the form of a multilayered and infinite multiplication of Murphy’s bookcase and bedroom. Catching himself at one bookcase and instance, Cooper looks from behind the books on a shelf both at his daughter in her present and as a young child in his—or is it her?—past. In tears at the sight of Murphy, who seems to sense the presence of what she used to call her “ghost,” Cooper desperately tries to communicate the data that will save her and a multitude of others, but he cannot do so directly. Suffice it to say, that with great ingenuity (and without “spoilers”), he eventually finds an indirect way to do so—and one in which Murphy realizes that the “ghost” is her father. Throughout this temporally complex and emotionally intense climax, the earthly and cosmic remain infinitely separated yet are also intimately connected. Indeed, there are no temporal paradoxes here because multiple pasts, presents, and futures are all seen as both simultaneous and true.

Thus, even if astrophysics tells us it is impossible to revisit the past to change the future, what this stunning and mind-bending sequence reveals is something, in fact, quite simple: it is certainly possible to alter whatever present we happen to presently occupy. Brought together across different spatial dimensions of the same present—one, the intimate interior of an earthly bedroom, and the other, the infinite exteriority of the cosmos—there will now be a future for Cooper and Murphy, as there will be for their larger human family. And so, in the epilogue, in quite different spatial and temporal circumstances—and in the flesh—father and daughter will meet once again in what Nolan renders as a fully realized, if mortal, future.

The immense urgency that fuels the temporal themes of Nolan’s ravishingly beautiful and philosophically profound film also resonates in lines from Dylan Thomas’s greatest poem, “Do not go gentle into that good night,” which, spoken in dialogue and voiceover several times, serve as both the narrative’s commentary and chorus. However, the poem’s exhortation to “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” seems directed less at the film’s characters than at its present audience. Indeed, Interstellar’s call to action urges all of us watching in our own dying light to do more than passively resign ourselves to imminent extinction.