Coolie

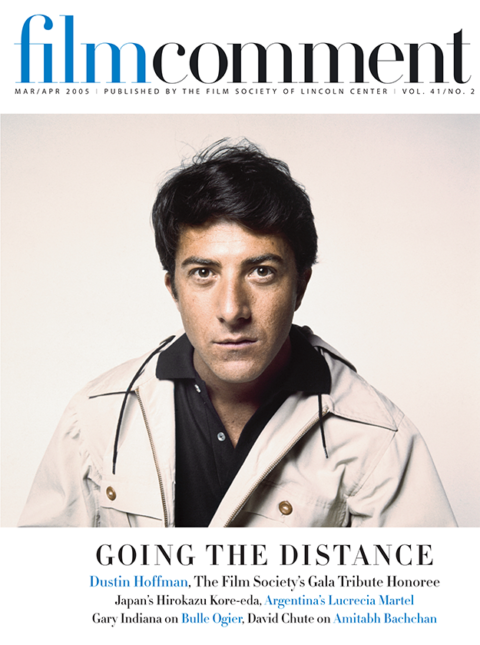

I love watching Amitabh Bachchan dance. Which is not to suggest that the most durable star in the history of Hindi cinema is celebrated for his fancy footwork. In fact, apart from his undoubted acting chops and the sheer force of his brooding masculine charisma, he is most fervently admired for his verbal gifts: the sonorous baritone that makes all his setpiece speeches sound like Mosaic proclamations, and the flair for mimicry he exploits as one of the first Bollywood actors to adopt authentic Bombay street slang in his gangster roles. Bachchan is also one of the few Bollywood stars who has occasionally recorded his own playback tracks. In contrast, Bachchan’s typical terpsichorean style is about as basic as it gets, a sort of blue-eyed Punjabi variant on one of Zorba the Greek’s “hoop-hah” strut ‘n’ shrug routines. But when he dances, Amitabh Bachchan is a great actor. Decked out in what looks like a gaucho outfit in Don (78), prancing and preening next to the staggering Zeenat Aman (India’s answer to Claudia Cardinale), he looks less like a performer working through a carefully choreographed routine than a man enjoying himself, and enjoying life.

It is well known that when Bachchan tried to trade up to acting in the late Sixties from his job as a shipping company executive he was at first dismissed by producers as “too thin and too tall.” It was probably no accident that in his early films he is often shown slumped over tables or sitting behind desks, playing brooding young poets and doctors, roles that echoed his own patrician upbringing as the son of the famous Hindi poet Harivansh Rai Bachchan. At 6’3″, however, Bachchan is not really all that tall by American standards. He doesn’t tower over his strapping co-star Dharmendra in Ramesh Sippy’s Sholay (Flames, 75), the groundbreaking “curry Western” that confirmed his arrival as a new kind of superstar, a disaffected Angry Young Man who takes the law into his own hands. But with his short-waisted, long-legged physique he can look downright gangly, and when strategically photographed he becomes an honorary giant.

Trishul

Bachchan has a classic standing-tall entrance in Yash Chopra’s Trishul (Trident, 78), using his cigarette to light a fuse and then sauntering calmly away as a mountainside erupts behind him. The script for Trishul was one of several, beginning with Zanjeer (The Chain) in 1973, in which the writing team of Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar (aka Salim-Javed) originated the Angry Young Man persona. The image owes something to Clint Eastwood, obviously, but the Bachchan hero (who is almost always named Vijay, Hindi for “Victor,” the victorious one) is not a classic loner in the Hollywood cowboy mold. As the critic Vinay Lal points out in his essay “The Impossibility of the Outsider in the Modern Hindi Film,” the loner in his pure form is a type unknown to Bollywood. In order to seem at least vaguely relevant and plausible to an Indian audience the Bombay hero has to be firmly enmeshed in a network of family and social ties. Trishul‘s Vijay isn’t a generalized existential rebel but a man with a mission, setting out systematically to destroy his own father (Sanjeev Kumar), a megalomaniac industrialist, in a highly entertaining series of sharp-practice business deals. This violation of a taboo has a distinct subversive appeal in its own right, but in Bollywood terms it can only be justified as a response to an even greater violation: Vijay is out to avenge his sainted mother (Waheeda Rehman), who was abandoned, unwed and pregnant, so that her fiancŽ (Vijay’s dad) could marry up into a rich family. This betrayal lays the groundwork for the financial empire his son attempts to destroy. To honor one imperative of his duty as a good son, Vijay must violate another, a contradiction he chews over obsessively in a series of setpiece speeches.

Zanjeer

It has been suggested that even when Bachchan was playing proletarian characters he always walked “with the posture of an aristocrat.” What is often most thrilling about his confrontations with authority is not so much his physical courage as his easy assumption of equality: this guy never feels outclassed. “You see a certain grace about that character,” suggests Akhtar. “So many other actors have tried to ape Amitabh, but they’ve failed. Because they don’t have the sophistication and the tehzeeb [culture] that he grew up with. As an actor, Amitabh’s anger was never ugly. Other actors mix anger with arrogance. Amitabh’s anger was mixed with hurt and tears . . . But I’m afraid that in later pictures even Amitabh developed that arrogance.” (Kabir, Nasreen Muni. Talking Pictures: Conversations on Hindi Cinema with Javed Akhtar. New Delhi: Oxford University Press: 1999.)

By the mid-Eighties this subtly inflected screen image had devolved into a subaltern superhero myth in pictures like Coolie (83) and Mard (He-Man, 85), garish big-budget cartoons aimed squarely at the groundlings. The Bachchan heroes in these films don’t have to tear themselves in two in a fruitless bid to find a place in the world because they aren’t really worldly beings. They are proletarian demi-gods, the sweat-stained masters of all they survey. We can tell that Allah looks with favor upon Bachchan’s Iqbal in Coolie because this Muslim railway porter is assisted in his quest for justice by a magical animal, a gorgeous falcon that dive-bombs the labor leader’s sneering enemies. And in Mard Bachchan’s mother-fixated tongawalla (cart driver) leads the oppressed masses to victory with the help of both a deus ex machina dog and a superintelligent horse.

Coolie

These films are perhaps best viewed today as comedies, and it seems unlikely that all of the humor was inadvertent: Bachchan’s performances in them have an unmistakable glint of irony, and, like director Manmohan Desai, he seems to have thrown himself into them mostly as a lark, only a few steps removed from the intercommunal vaudeville of their earlier Amar Akbar Anthony (77). On the other hand, it’s possible that an element of cynical calculation came into play in terms of their impact on the mass audience. This was also the period, after all, in which Bachchan was elected to India’s Parliament as a Congress Party candidate from his hometown of Allahabad, and the films do somewhat resemble the flat-out mythologicals that helped confer an aura of godlike infallibility upon the South Indian actor-politicians M.G. Ramachandran and N.T. Rama Rao (see Film Comment, May/June 1987).

Within even the worst of his movies Bachchan remains an honorable performer, and in his best roles he leaves his superstardom at the door. In Ramesh Sippy’s Shakti (Power, 82), which was made only a year before the rabble-rousing Coolie, Bachchan worked earnestly to serve a project in which he was bound to be overshadowed by his legendary co-star, Dilip Kumar, a revered veteran of the Golden Age and one of Bollywood’s all-time greatest actors. In Salim-Javed’s script, Bachchan’s Vijay is the son of a rigidly dutiful police inspector, an unbending Father India figure who refused to negotiate with the ganglord (the late Amrish Puri) who kidnapped Vijay when he was a child. The boy managed to escape on his own only because another member of the gang (Dalip Talil) took pity on him and looked the other way. As an adult, Vijay goes to work for this man, who is now a notorious smuggler—”The man who saved me,” he tells his outraged father, “when you were willing to let me die for the sake of the law.”

Shakti is the most nuanced and lacerating of the Angry Young Man films, because the pivotal conflict is located not outside the hero, in the realm of plot mechanics, but within: “The only person I am afraid of is myself.” Bachchan seems to deliberately damp down his trademark fiery acting style in order to harmonize with Kumar’s understated naturalism, and he has some lovely courtly romantic interludes with New Cinema icon Smita Patil. But while the film won several Filmfare (India’s Oscars) awards, including Best Screenplay, it was not a commercial success – in part, it seems, because it did not give Indian moviegoers the sort of iconic Bachchan they had come to expect. “In spite of being a megastar,” Akhtar says, “[Amitabh] did not let his stardom come in the way of playing the son. And he played the son and looked submissive, or passive, or frightened, or intimidated – as a son should look in front of a powerful father. He showed that he’s an actor first, then a star.” (Kabir, 66-67.)

Namak Halaal

But if Amitabh Bachchan the man could at times have made better use of his fame, a couple of other things need to be said: Bachchan has never gone in for the jingoistic Hindu nationalism favored by action stars such as Manoj Kumar in the Seventies and Sunny Deol since the Nineties. He has played Muslim and Christian characters in several films, and at the peak of his almost unimaginable popularity he was not all that protective of his glowering heroic image, alternating action roles with high-stepping comedies like Namak Halaal (82) or moody middlebrow romances such as Yash Chopra’s Kabhi Kabhie (76) and Silsila (81). He may not have been pro-active in the modern manner in terms of developing projects for himself, but he does seem to have been open to almost any kind of good role that came his way.

The mid-Eighties marked the pinnacle of Bachchan’s superhuman stardom: news of his near-fatal accident in 1982 on the set of Coolie brought the country to a standstill. But his Olympian eminence proved short-lived: he was implicated (falsely) in the Bofors bribery scandal that crippled the post-Emergency government of his childhood friend Rajiv Gandhi, and the yellow press turned against him. The situation looked even more dire when a high-profile multimedia production company launched in the mid-Nineties, Amitabh Bachchan Corporation Ltd. (ABCL), was done in by a series of commercial miscalculations. Most of his Nineties films were not successful, which seemed to confirm the widespread suspicion that Bachchan was a spent force. He was not easy to replace: in the mid-Nineties it took all three of The Three Khans (Aamir, Shah Rukh, and Salman) to fill the vacuum created when The Big B dropped off the A List.

Bachchan was able to work his way back into the limelight toward the end of the decade with a run that, when first announced, sounded like a comedown prompted by financial desperation: appearing as the host on Kaun Banega Karorepati,the Indian version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? And then, in the steamroller hits of the first phase of his comeback, such as Aditya Chopra’s Mohabbatein (Loves, 00) and Karan Johar’s Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham (Sometimes Happy, Sometimes Sad, 01), Bachchan reinvented himself as an imposing patriarchal figurehead of Hindu Family Values. A new generation of Indian moviegoers saluted his screen image by shouting out not quotations from his movies but his popular catchphrase as a TV quizmaster, “Lock kiya jaye?” (“Close the computer?”)

Mohabbatein

A throwaway shot early in Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham drew affectionate chuckles from the mostly-NRI (Non Resident Indian) crowd when I saw the movie in Los Angeles: Bachchan’s real-life wife Jaya standing on a chair to adjust her husband’s necktie. The effect depends on a number of factors in addition to the star’s famous height. It plays upon the Indian public’s sense of the Bachchans as one of Bollywood’s most durable couples, and upon the affection due to Jaya herself as a performer, a diminutive firecracker whose headstrong teenage characters in the Hrishikesh Muhkerjee films Guddi (71) and Mili (75) brought a recognizable type of modern, urban woman to the Hindi screen for the first time. Jaya and Amitabh met when he played a strong second-fiddle role in Mili, at which point she was much the bigger draw. But by 1999, one year after their 25th anniversary, Amitabh had been certified as the most popular movie star of all time in an online poll conducted by the BBC—a feat that was trumped, at least for me, when he became the first and only Indian actor memorialized in wax at Madame Tussaud’s in London.

Cynics might suggest that Bachchan looked like a wax dummy in some of his post-comeback films. In more than a few of them he seems to have been cast mostly for his nostalgia value, stuffed and mounted on a pedestal. But in the best of them, as the rigid headmaster of an exclusive men’s college in Mohabbatein, he looks more like something carved from granite. Bachchan clearly works hard to serve writer-director Aditya Chopra’s conception of his character, Narayan Shankar, as a man so stiffened by disappointment that he’s virtually immobile. In dramatic terms, after all, that’s exactly what Shankar is: an immovable object for obstreperous co-star Shah Rukh Khan to hurl himself against. It actually works for the movie that Bachchan looks like a strange visitor from another era, the ne plus ultra of all the stern father figures his Vijay characters rebelled against in the Seventies.

Over the past few years, and against all odds, Bachchan has managed to build upon his initial comeback status as a serviceable senior character actor. He is once again, in his sixties, a major leading man, a feat that is certainly rare enough in the annals of world cinema to be noteworthy. The lobby of a major NRI movie palace like the Naz 8, near California’s “Little India” in Artesia, seems to exist in a Seventies time warp: half of the coming attractions posters carry the Big B’s glowering image. Many of these roles look like middle-aged “veteran” versions of character types he has been embodying all his life: conflicted criminals in Kaante (Thorns, 03) and Boom (04), flawed honest cops seeking redemption in Khakee (03) and Dev (04), and patriotic military icons in Lakshya (Objective, 04) and Deewaar (Wall, 04). But these days he plays even these hyper-masculine roles as men close to his own age, happily long-married patriarchs with grown children. Perhaps this is the upside of living in a traditional society – that people who would long since have been put out to pasture in the West can still be seen as the “author backed” subject of the narrative.

Lakshya

His charisma is sorely needed, as no one in the current crop of younger actors has anything like Amitabh Bachchan’s moral authority, which is the grown-up distillation of his youthful anger. When the New Cinema stalwart Govind Nihalani (Ardh Satya/Half Truth, 83) made Dev, his Bollywood exposé of political complicity in communal violence, there was really only one viable choice for the voice-of-reason title role, an honest policeman fending off both Muslim and Hindu demagogues. Meanwhile, the Three Khans seem to have skipped over the seething Bachchan persona altogether in their search for role models, harking all the way back to the Shammi Kapoor hip-swivelers of the Fifties and Sixties who cajoled and schemed and danced their way to comfortable happy endings. And in a period in which the typical Bollywood blockbuster is designed to reassure the rising Indian middle class, the younger males (Vivek Oberoi, John Abraham, Arjun Rampal) are well-groomed good sons in expensive sweaters. In his best latter-day vehicles Bachchan relishes dispensing fatherly advice to these whelps, and to our delight, he is dancing again. In Yash Chopra’s Veer-Zaara (04) he is an irrepressibly affirmative role model. He almost single-handedly redeems Sameer Karnik’s formulaic Kyun! Ho Gaya Na… (Well! There You Are…, 04) with a high-stepping comic turn as a compulsive practical joker, the puckish deus ex machina in a blocked romance.

In Mohabbatein, Shah Rukh Khan, as a warmhearted music teacher, predictably wins his running battle with Bachchan’s harsh task-master, who has turned his back on the possibility of love and happiness. But in the film’s final sequence Khan still feels compelled to bend over and touch the feet of this literally monumental figure. Although Amitabh Bachchan’s prodigious stature is now (as it has always been) partly an optical illusion, it can’t be denied that in his sunset years he looks mightier than ever.