By Rachel Rosen in the March-April 2000 Issue

On Solid Ground

Sundance documentaries

Amidst the usual frenzy of the Sundance Film Festival, this year’s documentary competition felt like an oasis. Featuring less flashy subject matter and filmmaking, the section had a more dignified air than in recent years. Content dictated form; filmmakers generously gave voice to subjects without calling attention to themselves. Formal experimentation gave way to raw emotion, and the combination of weightier topics and skillful construction made for one of the most substantive selections in recent memory. Even The Eyes of Tammy Faye, a portrait of the former Mrs. Jim Bakker—narrated by drag queen RuPaul, and featuring chapter headings announced by a pair of hand-puppets—turned out to be more than the expected camp extravaganza, providing insight and perspective on a woman whose name usually evokes little more than an image of smeared mascara.

From the March-April 2000 Issue

Also in this issue

Throughout the documentary competition, issues of family dominated. The most devastating portrait of kin was Just, Melvin, James Ronald Whitney’s story of the steady ruination of his family by his grandfather’s acts of abuse, incest, and violence. The filmmaker’s missteps, among them overwrought voiceovers echoing quotes from interviews, are washed away by the swift current of the story and balanced by the family members’ nonplused perspective on their ravaged lives.

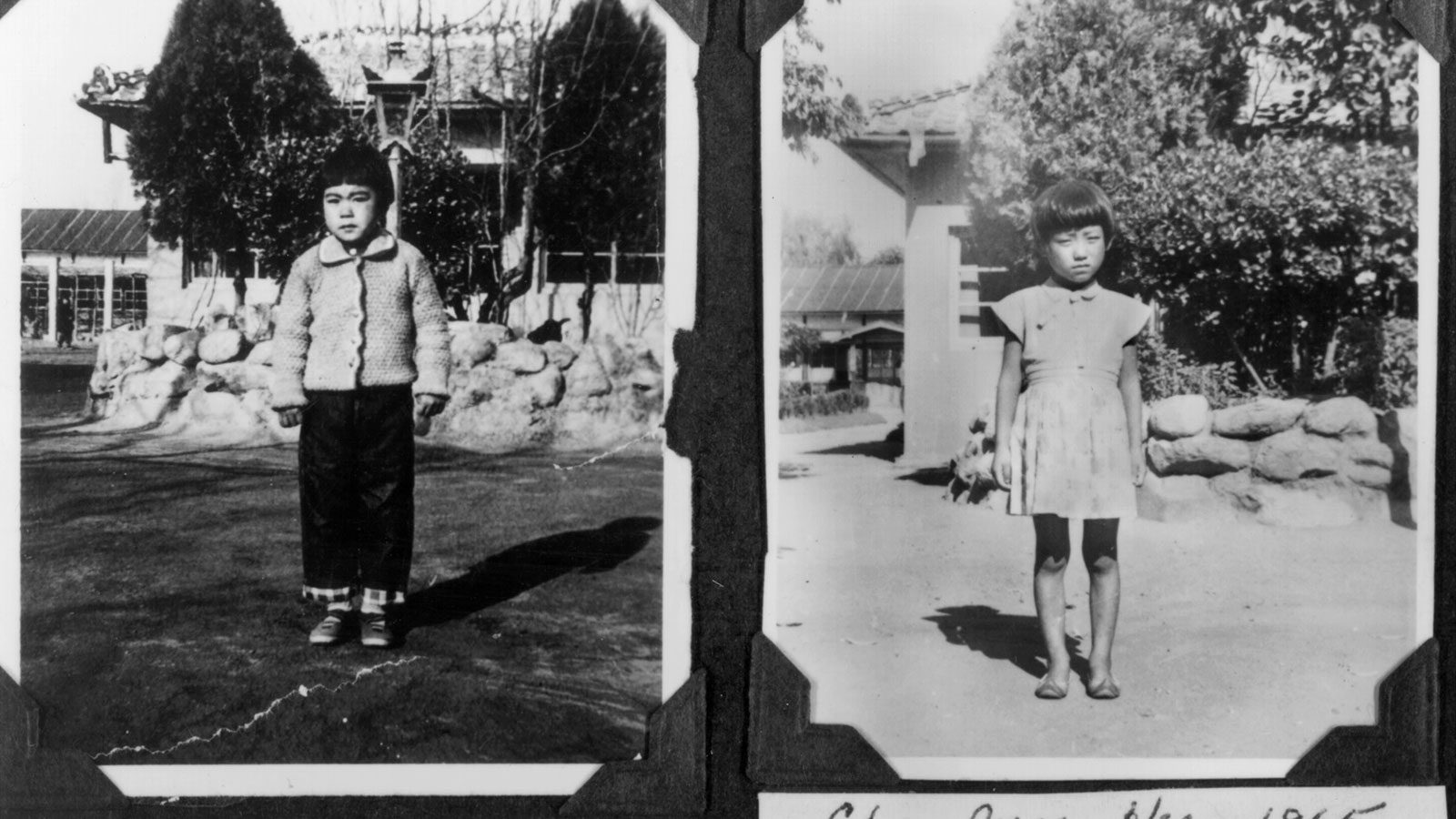

Another affecting exploration of personal ties, Deann Borshay’s First Person Plural, examines the filmmaker’s history as a Korean-born adoptee of an American family. Borshay’s discovery that her past is not what she thought, and that she has two families, raises questions of whether and how she can really belong to either one. The thought-provoking Sound and Fury uses one extended family to explore the issues surrounding the controversial cochlear implant, a revolutionary procedure that can enhance hearing in the deaf and allow for more natural speech. Success in acquiring verbal skills by deaf children appears to come at the expense of American Sign Language; many in the deaf community think that the implant threatens American Sign Language and the culture of its users. It is a familiar conflict of assimilation vs. cultural pride and self-acceptance, striking because deafness is more often recognized as a disability than a culture. The film is serviceably constructed, but the filmmakers’ biggest triumph was finding the family that is their focus. Two brothers of hearing parents, Peter and Chris Artinian, face difficult decisions about their children. Peter is deaf, and is a committed advocate of deaf culture, but his 6-year-old daughter Heather has developed a curiosity about the world of sound, from bird calls to crashing cars, and a desire to communicate more easily with hearing people. Chris and his wife Mari face the disapproval of Mari’s deaf parents when they decide in favor of an implant for their deaf baby. This one family, filled with intelligent, passionate personalities, enlivens every aspect of the issue.

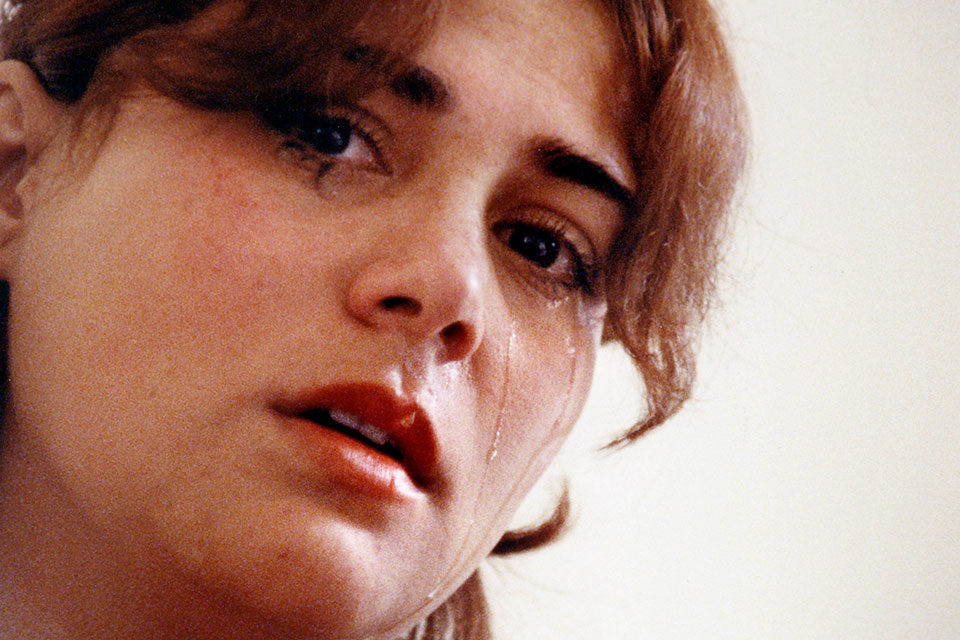

Well-Founded Fear

Superb craftsmanship could be found outside the family sphere in Well-Founded Fear, which focuses on the interview process that applicants for political asylum undergo with the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service in order to establish that they face danger or persecution if deported back to their countries. By putting this procedure under a merciless microscope, Shari Robertson and Michael Camerini raise questions about the entire refugee system. Well-Founded Fear has great empathy for its subjects on both sides of the process, from the applicants—victims of fear and bad advice, forced to relive horrifying and humiliating situations (unlike therapists, not all asylum officers supply tissue for their sobbing visitors)—and the immigration officers themselves, well-meaning government employees doing their best to cope with overwhelming responsibility and few verifiable facts.

For some officers, the slope from healthy skepticism to cynicism and mistrust is as slippery as a Park City ski run. The directors use a mix of interviews and beautifully shot observational footage to tell the story seamlessly. Narration and titles clarify factual points, and the filmmakers leave their questions audible when it is most expedient. They don’t comment overtly on the matter, but their subtitling of official interviews provides devastating evidence of the precarious dependence of the applicants on interpreters, and the damage that can be done by bad translation. Their varied method falters only in the epilogue, in which some applicants receive more detailed treatment than others, for reasons unclear, and in their use of lyrical images in a framing device involving the Statue of Liberty, a ferry ride, and water. This symbolic imagery seems superfluous when reality is so engrossing. As with most of this year’s documentaries, the strengths of the film were in more concrete places.