I am grateful to Roger Ebert for responding to my article in the spirit in which I wrote it, as the opening of a civilized debate. We agree more than we differ, but that won’t keep me from picking a few spats.

I do watch Siskel & Ebert & the Movies, and I watch it for the reasons most people do: to see the clips and enjoy the wrassling. I think the program has other merits, and said so in a sentence of my original article that didn’t make it into type: “Sometimes the show does good: in spotlighting foreign and independent films, and in raising issues like censorship and letterboxing.” The stars’ recent excoriation of the MPAA’s X rating was salutary to the max.

I don’t see Fox’s banning of Judith Crist as “the single most influential event in the history of modern newspaper film reviewing.” (If so, what are we to make of Fox’s brief banning of Siskel and Ebert this spring?) After all, 1963 was the year of Andrew Sarris’ “American Cinema” rankings in Film Culture, of Pauline Kael’s gnarly brilliance in Film Quarterly, and, on the mass-media front, of Time‘s “Film Generation” story, with a photo of Polanski’s Knife in the Water on the cover. Those events surely influenced readers and editors at least as much as Fox’s Crist-killing.

Whatever the causes, one result is clear. We now have more, and more knowledgeable, movie critics in the big slots (though some local reviewers have lost their jobs to make way for famous syndicated scribes like Roger Ebert). But we have less exciting movies to write about. And, as Ebert suggests, less excited moviegoers. “Serious discussion of good movies is no longer a part of most students’ undergraduate experience,” Ebert says. Go further: it’s hardly part of anyone’s experience. Popular taste, even sophisticated popular taste, is cramped and conservative—especially as it relates to film. TV critics can help persuade 40 million Americans to savor the supreme weirdness of David Lynch’s Twin Peaks. Movie critics can’t get a tenth of that number into the theater for any quirky independent or foreign film.

Not long ago, after I panned the popular film Pretty Woman in Time, readers barraged me with the overripe fruit of their scorn. “Please find someone,” a correspondent wrote, “whose tastes are at least similar to a majority of the people who pay to see movies.” Perhaps another swatch that didn’t make it into my original FILM COMMENT article will answer this reader. “The presumption is spectacular: that a critic’s prejudices are supposed to reflect and anticipate the prejudices of every potential moviegoer. In this view we’re not analysts, we’re handicappers—not John Madden but Jimmy the Greek.”

The only solution, if a critic is both to speak his own mind and act as a bellwether of audience whim, is to write about a film: “It stinks. You’ll love it.” That’s still presumptuous. How do I know who’ll love a movie? And who is “you” anyway? I’m not speaking to one reader, whose tastes I know intimately. My job isn’t to predict what movies are going to be popular; that’s what studio executives are paid for. And it isn’t, primarily, meant as a consumer service. It’s to enlighten the reader through my knowledge of movies and entertain him with my play of language. Which is what I try to do at Time and FILM COMMENT.

Ebert writes about the straitjacket of space at Time; he even took the trouble to compare the word-count of my shorter reviews with the verbiage expended on Siskel & Ebert. But space isn’t the only dominatrix. Yes, S&E devoted more words on their show to Blue Steel than I did in Time. And still, I’d argue, they had less to say. Their discussion was pretty much limited to whether the film was a good or bad representative of the cop genre. Matters of style, of Kathryn Bigelow’s fine directorial hand, of Ron Silver’s hyperkinetic, antirealistic acting—the matters that mattered in Blue Steel—were ignored. In my 267 Time words, you would find those issues addressed. You’d just have to bring your magnifying glass.

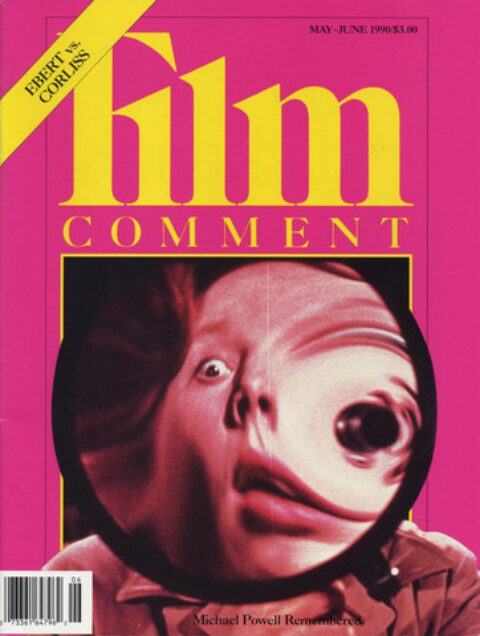

When I came to Time, in 1980, I knew that the job offered different restrictions (of space) and rewards (of exposure) from my stints at New Times and SoHo News. One thing that made the tradeoff attractive was knowing that at FILM COMMENT (where I’ve hung on in some editorial capacity or other for two decades now) I could continue to write at length on film issues and, just as important, assign others to write. Pretty good twin perks, which, I am assured by the magazine’s current editor, will continue. So my critics piece is not a “farewell article”; I’ll be at least as much a presence for Jameson’s FILM COMMENT as I was for Jacobson’s.

Does this splitting of my work—into writing reviews for Time and criticism, if you will, for FILM COMMENT—trigger a “mid-career crisis”? Well, I’ve had my share, though more at the Film Society of Lincoln Center than at Time. In a more general sense, I do accept Ebert’s argument. I might even ask: “Have critics lost touch with movies?… I suspect that we, no matter what our ages, have reached a midlife crisis, a menopausal anomie…. We are beyond being shocked or impressed. The thrill of discovery is gone.” In fact, I did raise these questions, in just those words, in a 1986 FILM COMMENT article that eventually got around to considering Out of Africa. One of the pleasures of writing for this magazine is that you can take forever getting to the point, and then discover that the “forever” is the point.

On Tom Cruise, the facts are simple: The relevant Time editors and I saw Born on the Fourth of July, thought the movie and especially Cruise’s performance were worthy of cover consideration, sold the idea to Time‘s managing editor, and received the star’s cooperation for the interview that is usually part of such a profile. (We got no window of exclusivity, nor did we ask for one.) Cruise didn’t tell us to do the story, and we might well have done it even if he had declined to participate. (We nearly came to that last year, when a proposed cover subject said he was too busy for us. “Let’s do the cover anyway;’ said our managing editor, who is famously unwilling to be dicked around by publicists. To me he added, “I’d rather read what you have to say about him than what he has to say about himself.”)

Time, in other words, was not in Cruise’s control. It ran whom it damn well pleased on the cover—as it used to do, as it still does. And I wrote what I damn well pleased: a mixed review of the film encased in an assessment of Cruise’s career. I’d summarize the piece on Cruise and Fourth of July as “liked him, wasn’t crazy about it.” Maybe the vivid prose in my lead reads like flackery to Ebert, but the flacks don’t always take it that way. They know that a Time cover does not guarantee a favorable review. In cover stories I’ve knocked Field of Dreams, Fatal Attraction, and the movies of Nastassja Kinski and Bette Midler. Our Mississippi Burning cover included a sidebar (not by me) lambasting the film as a Hollywood whitewash.

Pretty brave, eh? Naaah. As Ebert indicates, the publicists of these films cared less about what Time’s critics said than that their clients got on the cover. They were interested in the quantity, not the quality, of the coverage. That’s why they send pix to Time and clips to Siskel & Ebert; it’s all free publicity. That may even be why some magazines employ some film critics. One respected periodical recently hired a reviewer known mainly for his effusive blurbmongering. Howcum? The consensus belief: the writer’s quotes get the magazine’s name in movie ads. Devising copy for the publicity machine need not be a despicable craft (I still treasure USA Today critic Mike Clark’s appraisal of some forgettable actioner: “Makes Rambo look like Rambeau”), but it’s not what I’d put first on my job application.

For Roger Ebert, that function is even more confining. Ads usually yoke him to Siskel, Siamese-twin style, and quote him not with an adjective but with a thumb. I’ll bet that, sometimes, he’d like it to be a finger.

As for Last Year at Marienbad, by the way, I give it a 10+.