By Sheila O'Malley in the January-February 2018 Issue

Love, After a Fashion

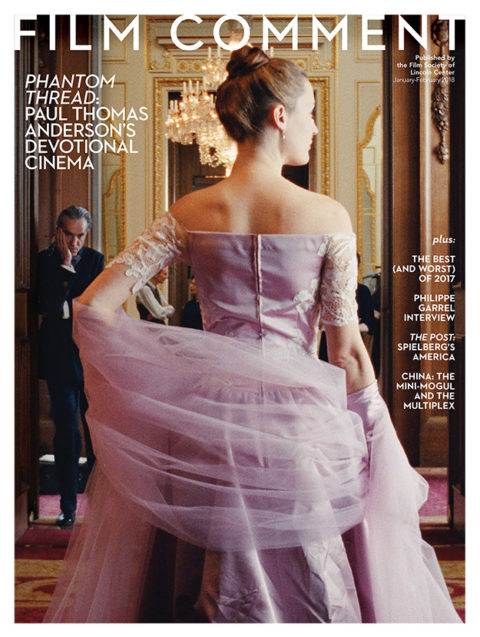

With elegant force, Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread curls round an ineffable, unstable romantic attention without which life is unlivable

I have always had to have clothes made for me because of my unusual shape—broad shoulders, narrow hips . . . I can see if something goes wrong during the making. And I stop it. I have no fur coat. I haven’t the courage anymore. This one isn’t mine. Balenciaga sent this over because he thought it was cold.”

—Marlene Dietrich, interview with The Observer, 1960

In the middle of George Cukor’s 1939 film The Women, the ladies attend a fashion show. As Sibyl Harris welcomes the audience, the camera slowly pulls back, showing the palatial room, the women chattering, knitting, hungrily waiting for the clothes to appear. The Women is in black and white, but the fashion show—featuring smiling models playing tennis, tossing around a beach ball, and feeding monkeys at the zoo, all while wearing gorgeous clothes designed by Adrian—is in vivid Technicolor. The reds, blues, and whites gleam off the screen. The film stops in its tracks for a full five minutes to allow the audience time to indulge their tactile responses to fabric and colors and shapes. Cukor doesn’t bury the lede: most people enjoy looking at beautiful people wearing beautiful clothes. That’s reason enough for the display. Such sequences—along with musical numbers (there’s always a chanteuse-in-a-nightclub scene)—were common in the “women’s pictures,” musicals, and even dramas of the era. There was no embarrassment about the convention at the time, and why should there be? Women are avid moviegoers, then and now. Fashion shows were (among other things) an act of generosity on the part of the filmmakers and studios: “We know who you are out there in the dark. We’ll make sure you get your money’s worth.”

From the January-February 2018 Issue

Also in this issue

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, Phantom Thread, a portrait of a fictional fashion designer in the couture scene of 1955 London, indulges in similar revels, placing the film firmly in the tradition of the melodramatic women’s pictures of the 1940s: it’s filled with achingly vivid close-ups (Anderson also shot the film) of shining colored threads, needles piercing thick fabric, rough-edged hand-sewn labels, intricate lace patterns, and rich cloth falling in sculptural folds. As with The Women, fashion isn’t necessarily the point of the film, but fashion focuses the energy of every character like a particularly single-minded prism. Pooh-poohing the importance of fashion in this world would be like saying “It’s only a game” to football fans on Super Bowl Sunday.

The film was co-written by Anderson and Day-Lewis over a number of years spent obsessing on the topic (Day-Lewis goes uncredited), and is, in part, a fascinating character study of a fastidious solitary man devoted to the creation of the graceful silhouettes in his mind’s eye. Successful obsessives are usually reclusive creatures. What happens when a person like that falls in love? Can a person like that fall in love? What is the difference between love and aesthetic appreciation? Can you be a muse and also have needs of your own?

Reynolds Woodcock (Day-Lewis) runs his fashion line out of his London townhouse, where every morning a staff of women line up outside the door in the pre-dawn light, waiting to be let inside to climb up the narrow staircases to their lofty perches around the mannequins and seamstress tables. Running Woodcock’s affairs like a tightly wound, extremely expensive watch, is his sister Cyril (Lesley Manville), whose dark-fitted suits cut a terrifying swath through the house, her black heels clacking on marbled floors. As fearsome as Cyril is, the relationship with her brother is one of tender silent accord, her ESP tendrils anticipating his moods. He refers to her, fondly, as “my old so-and-so.” In an early scene, Reynolds admits to Cyril, out of nowhere, in one of his moments of disarming openness, “I have an unsettled feeling based on nothing I can put my finger on.” He is haunted by the memory of his long-dead beloved mother. When he speaks of her, his voice gets soft and tender, his eyes float to a faraway space of memory. The loss is still extremely close. He is the stereotypical Great Man with work to do and Cyril makes sure he has the physical and mental space for it, even and including breaking up with his periodic love interests for him.

Into this duo enters Alma (Vicky Krieps), a clumsy girl with flushed cheeks who catches Woodcock’s appreciative eye when she waits on his table in the hotel restaurant of an isolated seaside town. (Flashes of James Joyce meeting Nora Barnacle—who would become one of the most famous muses of the 20th century—when she was a waitress in Dublin’s Finn’s Hotel). Woodcock is captivated by Alma. She, in turn, is flattered by how he looks at her. Even what she considers to be her flaws are assets in his eyes: “You have no breasts,” he says to her, in what could be construed (understandably) as a devastating indictment. “I know. I’m sorry,” she says. “You’re perfect,” is his flat reply. (This exchange takes place during their first date, which includes an impromptu dress fitting.) The lines blur between a Pygmalion/muse arrangement and something more intimate when Alma moves into the London townhouse, splitting her role as artist’s model and girlfriend. The inseparable Reynolds and Cyril must now admit a third, and, as everyone knows, three’s a crowd. A clear reference point for Phantom Thread is Hitchcock’s 1940 film Rebecca, in which a young naïve woman (Joan Fontaine) marries a widower (Laurence Olivier), who is still in thrall to his perfect dead wife, Rebecca. The antagonistic housekeeper of the home, Mrs. Danvers (Judith Anderson), lets the new Mrs. de Winter know in no uncertain terms that Rebecca will never be dethroned.

Cyril keeps an eagle eye on the development of the relationship, waiting for the inevitable moment when she will be called upon to intervene. The situation would be intolerable to a more conventional or easily cowed woman, but Alma is not conventional, nor is she easily cowed. She is, if anything, stranger and more eccentric—more driven—than Reynolds. On the surface, her campaign to enter the inner sanctum of not just his house but his heart may sound like clichéd, even retro, material: the woman teaches the reticent man the glories of love. Audience members may want to intervene and tell Alma to forget this guy, find a man who will reciprocate. But Alma has other plans. She senses his sadness, senses his loneliness is so complete as to be absolute. How she goes about breaking him down is so “out there” it’s almost as radical as the frogs raining from the sky in Anderson’s Magnolia. Alma, at first glance a simple and easily flattered woman, reveals a will as intractable as Cyril’s. Cyril and Reynolds have met their match.

To the deep credit of both Day-Lewis and newcomer Krieps, this love story reverberates with real feeling, emotions ricocheting off the claustrophobic walls. The characters’ arguments splutter, overlap, in ways that feel wholly unscripted. We don’t argue with one another in perfect sentences. Anderson generously gives scenes lots of space for behavior, listening and talking, pauses. Unlike other clichéd Great Men Humanized by Love narratives, Phantom Thread maintains its sense of humor (the film is very funny), its suspicion of shallow catharses, and its respect for the individualism of the characters.

Phantom Thread comes a decade after the fruitful collaboration of Paul Thomas Anderson and Daniel Day-Lewis in the robber-baron epic There Will Be Blood, adapted from Oil!, the novel by Upton Sinclair (with the triumphant ghost of famous muckraking journalist Ida Tarbell as its guiding spirit). There Will Be Blood won two Oscars (for Day-Lewis and for Robert Elswit’s cinematography). In the Q&A following the screening of Phantom Thread at the Directors Guild of America in New York, Anderson mentioned his desire to work with Day-Lewis again after There Will Be Blood, and through a series of fits and starts they came up with the idea of doing a film about a couture designer in 1950s London, at a time when the country was hauling itself out of the austerity conditions of World War II. The two were inspired partially by flamboyant designer Charles James, whose gowns (or “creations”) were described by Virginia Woolf as “diabolical, and geometrically perfect.” But the primary inspiration was Basque-born Cristóbal Balenciaga, a reclusive genius called “the master of us all” by Christian Dior. (“The Master of Us All” is the title of a 2014 book about Balenciaga, required reading for everyone involved in Phantom Thread.) In an interview with Film Comment, Mark Bridges, who has designed the costumes for all of Anderson’s films (and was nominated for an Oscar for Inherent Vice), described the daunting scope of the costuming for Phantom Thread, a film about clothes: “We had to decide what are the designs of the couturier that is Daniel’s character. Are his looks like Norman Hartnell? Hardy Amies? Or is it our own thing? What level of success is he? Is he a Balenciaga? Or a John Cavanagh?” Elsewhere Bridges has said that Anderson “wanted to connect things that happened in Reynolds and Alma’s relationship and turn them into couture garments, so you can see that he’s autobiographical in some of his creations.”

And so it is Alma—not Woodcock’s splendid “creations”—who inhabits the center of the film, gathering her strength for an assault on the fortress that is the House of Woodcock. “I am trying to love him the way I want to,” she declares to the horrified Cyril. Over the course of the film we see what it is that Alma loves in Reynolds. Day-Lewis’s work is grounded in an extremely specific emotional reality. It is not a “flashy” part, like Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood. Day-Lewis is subdued, pained, interior, with breathtaking moments of openness. Reynolds is not malignantly cruel. He is a brilliant man with emotional limitations. There are vestiges of the classic screwball formula in Phantom Thread, where a workaholic nerd (like Cary Grant in Bringing Up Baby) is overrun by a free-spirited dame who will not take no for an answer.

Anderson’s is a versatile and inquisitive mind. His work is firmly rooted in technique, his awe-inspired response to Max Ophüls’s camerawork in The Earrings of Madame de… showing his awareness of the integral connection of form to story. Phantom Thread has a forbidding kind of beauty, with cold morning light falling through the windows on the trio’s faces during awkward “family” breakfasts. As the film moves into Reynolds’s work spaces in the upper stories, the light gets warmer, softer: it is where he feels most at home. Occasionally, Anderson uses dissolves between scenes, a throwback to the unembarrassed melodramatic films in the era in which Phantom Thread takes place. Frequent Anderson collaborator Jonny Greenwood composed the emotionally and orchestrally intricate score that weaves itself through scenes, a constant presence, tying sequences together and intensifying the atmosphere in that already intense house.

Paul Thomas Anderson is one of the few heirs to Robert Altman, that master of sprawling ensemble films. (Altman handpicked Anderson as his proxy during the filming of A Prairie Home Companion, in case he became too ill to continue.) Unlike the orchestral Boogie Nights and Magnolia, Phantom Thread is a chamber piece, featuring three instruments. There are only a couple of scenes outside the townhouse. It is a hermetically sealed world, where Alma tries to throw open the windows. Following on the heels of the gorgeously paranoid Inherent Vice, where the action careens around all of Los Angeles County, Phantom Thread is intimate, quiet, cramped, relying heavily on the interdynamics of the three strong-willed main characters and their push-pull shared power struggles. The character arcs have been set up with meticulous care.

In reflecting on Anderson’s body of work, with all of the memorable scenes in his films—dazzling multi-character, multi-location sequences tied together by music, or stunning two-person face-offs (the staring contest between Philip Seymour Hoffman and Joaquin Phoenix in The Master comes to mind)—his romantic scenes inhabit some kind of sweet spot, tender as a bruise on an apple. Loving someone is easy. Being loved is tremendously difficult for Anderson’s characters. There’s the heart-stopping final scene of Magnolia, featuring John C. Reilly talking so quietly to Melora Walters that we cannot hear what he says, but we know his unconditional acceptance of her is literally changing her life. There’s the entirety of Punch-Drunk Love, where Adam Sandler’s tormented Barry joins the rest of humanity—finally—through the experience of being loved. In Inherent Vice, there’s a piercingly bittersweet flashback where Doc (Phoenix) and Shasta (Katherine Waterston) run barefoot through the rain, searching for a drug dealer’s apartment, all to the strains of Neil Young’s “Journey Through the Past.” It is a sequence so joyful it breaks your heart, because it takes place in the past, and the past is gone. In Paul Thomas Anderson’s work, love can be—quite literally—a miracle. People are scarred by life, their emotional resilience decimated by disappointments and neglect. But sometimes love is offered and, as Blanche DuBois says, famously, in A Streetcar Named Desire: “Sometimes—there’s God—so quickly!” That’s the redemptive romantic journey of Phantom Thread, where Reynolds says to Alma at one point that she may very well keep his “sour heart from choking.”

There can be no “happily ever after,” not really, not for this pair. But all is not lost: like the Elvis Presley song says, “True love travels on a gravel road.” The road in Phantom Thread, in direct contrast to the exquisite garments floating through immaculate rooms, is distinctly bumpy. The trajectory of this unique romance has the same tenuous crescendo of the final paragraph of Annie Proulx’s The Shipping News, a similar story of two people, holed up in their cumulative hurts, who—without seeking it out—are changed by love, by being loved:

Water may be older than light, diamonds crack in hot goat’s blood, mountaintops give off cold fire, forests appear in mid-ocean, it may happen that a crab is caught with the shadow of a hand on its back, and that the wind be imprisoned in a bit of knotted string. And it may be that love sometimes occurs without pain or misery.

It may not be, too. It could go either way. With Reynolds and Alma, nothing is a done deal.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other places including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.