By Howard Hampton in the May-June 2017 Issue

Blank Generation

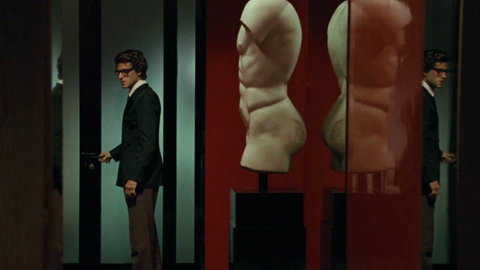

In Bertrand Bonello’s perfectly unsettling Paris-set thriller Nocturama, young terrorists find that the forces of destruction and consumption hold equal power

It’s after midnight in Paris. Following a cluster of terrorist attacks, a clean-cut young man (Finnegan Oldfield) slips away from his department store sanctuary to take a quick look around. A few police cars speed by; a helicopter buzzes overhead. (A roof-level shot offers a bird’s-eye view of a different feather: unmoored lantern balloons float upward, like a flock of mini-UFOs or decorative drones.)

From the May-June 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

The man strolls past a burning car and finds a young woman sitting on a bicycle. He asks what she’s heard. She says the authorities have leads but nobody’s claimed responsibility. It was bound to happen, the girl repeats somnolently—“and now it has.” Her shrug conveys a formidable mixture of acceptance and apathy. “Some people are overjoyed. And then you see others crying…” Her fatalism suggests a blanker revision of Doris Day’s “Que Sera, Sera”: “Whatever will burn, will burn / The future’s not ours…”

The anodyne-looking, multicultural, vacuum-packed terroristas in Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama represent a delicate, desiccated balance of nihilism and naïveté. Baby-faced bomb-setters who in the same breath know too much and absolutely nothing, they’re as much the offspring of a one-night stand between The Devil, Probably and The Breakfast Club as the muted, milquetoast afterbirths of La Chinoise or The Third Generation. Photogenic and unprepossessing as an MTV France ad campaign, this death-bent mild bunch is as oblivious, unformed, and devoid of character as the mannequins in that department store where they attempt to crash overnight.

Launching with a postcard-majestic aerial view of the city, Nocturama translates the antiquated splendor of an urban grid that has evolved over centuries into a Ground Zero bull’s-eye. Broken into day and night sections, the movie is by day a painstaking timeline that juxtaposes the hopscotching propulsiveness of a procedural thriller (when, where, how, but only a few trailing breadcrumbs of why) against the awkward, play-acting details of nervous kids attempting to execute a highly coordinated series of destructive acts.

Metro maps, station signs, landmarks, and time stamps are regularly displayed, as all the while Bonello assimilates simultaneous perspectives and temporal backtracking with diagrammatic precision. Small uninflected activities—a boy photographing some putty-like substance plastered on a subway corridor wall, the cell members ditching cell phones in trash cans—take on incremental significance. The director is scrupulous about maintaining our spatial bearings even while gradually undercutting our mental ones. In the tick-tock movements of the film’s early Paris Metro sequences, where members of the group assemble, prepare, fidget, and disperse along different routes, there are intermittent soundtrack bursts of a burbling Tangerine Dream-y pulse. (Like John Carpenter, whose Assault on Precinct 13 informs the conclusion of the film, Bonello composes his own electronic scores.)

The movie’s adamant, Google-Earthly focus on time, place, and looping continuity will suddenly dissolve into a world shorn of a past: a train emerges from the underground into a glassy metallic cityscape that could be Los Angeles or any other handsome, depersonalized 21st-century Metropolis. Objectivity can feel like the core of Nocturama’s central nervous system, but at night ritualistic dream-images crop up that deviate into mordancy: a ghost/hallucination casually recounts his death; a child-terrorist dons a golden mask; Hamza Meziani’s introverted, sheepish Yacine commandeers an upscale go-cart and weaves a Shining path through merchandise aisles. Tailing these average specimens/subjects with his camera (a signature breathing-down-their-necks move of Bonello’s), the movie plays off their youthful inconspicuousness: their improbability as perpetrators lends an extra layer of ambiguity, and exasperation, to their acts.

These rookie robo-guerrillas go about prepping and primping with indecipherable resolve. Laure Valentinelli’s Sarah is an especially impenetrable presence: wearing the constant sullen expression of a deposed teen queen (a leatherette Marie Antoinette), she plods through the movie leaving a perfume of curdled entitlement, faraway cat-eyes staring off into space. Martin Petit-Guyot, as the haughty André, who uses his connections to infiltrate the Ministry of the Interior, is pure M. Petit-Bourgeois Anarchist. Possibly cast for his funny resemblance to The Devil, Probably’s Antoine Monnier, his André suggests that film’s all-negating Charles if he’d gotten a civil servant haircut and a minor attitude adjustment, from suicidal to homicidal.

Elsewhere, Manal Issa’s jumpy, open-faced Sabrina has checked into a hotel and is surveilling the Joan of Arc statue she’s going to set on fire, with an ultra-banal music video playing on television (“Champs-Élysées,” a dopey Franco-rap song whose “I don’t give a shit” refrain and vacuously diverse posse is dryly refracted in the film itself). Confronted with anything unanticipated (like genuine, as opposed to theoretical, violence), our youth platoon’s composure starts to falter: the synchronized blasts go off as planned, but there’s an elliptically presented, shots-fired confrontation with a security guard; one of the kids steps into traffic and is hit by a car. Little missteps begin to add up as they make their ways, a few huffing and hyperventilating, to their rendezvous.

For the interior, night section of the film, Bonello assembles the whole group, Avengers-like (or -Lite), to wait out the storm after-hours in the store’s deserted showrooms. There, he fixes the conspirators inside a disjunctive, elegant bubble: outside time, trapped in an anxious, fractious Exterminating Angel sleepover. Grimly frolicking or aimlessly wandering, they try on designer clothes, boom Willow Smith’s “Whip My Hair” through Bang & Olufsen speakers (“She was 10 when she sang this. Seen the video? It’s totally sick!” “Who cares? Check out the sound. It’s awesome, huh?”), arrange dolls, bicker after Oldfield’s David invites a homeless couple inside to join them for a late supper (only one of about a dozen daft moves on their parts), and gawk at news footage of their city-stopping handiwork on silent banks of flat-screens. “We did what we had to do.”

Having laid out the attacks in studious, tenaciously neutral fashion, Bonello turns on a more assertive sardonicism here. (I nearly typed “sadism”—there is more than a touch of that, too.) His stranded sitting ducks are set up in a neat row, killing time and kidding themselves in a gilded shooting gallery. (In the last act, a heavily armored team of police—or soldiers—will of course storm in and pick them off, like popping bubbles, one clean shot at a time.) Within the tense, efficiently demarcated confines of this luxe commercial space (the same building was also a memorable location in Leos Carax’s equally noctura-riffic Holy Motors), the director can give militant nonentities enough rope to get lost, act tough, play dumb, and gradually start to realize the hopelessness of their cornered position. Best of show: Yacine coming face to faceless with a dummy wearing the exact same outfit he’s put on.

Bonello can’t resist repeating this doppelgänger gag later, for undue emphasis, but given the dicey nature of the subject matter, its affectless tenor, and his pointedly abstract treatment of terror, this spot of heavy-handedness may not be a bad idea. (He was editing the film right when the Bataclan attack occurred.) Everything in the movie’s route to this point is bound up in multiple meanings/interpretations/effects of vainness, misdirection, disintegration, socially mediated posing, and above all diversion.

Nocturama deals with terrorism through a very well-thought-out maze of smoke and mirrors. It’s problematic on purpose (mostly), not intended as a portrait of real-world terrorists but an allegory of nihilism and decadence. (André offers the closest thing to the logic behind the attacks while talking about gaming the university exam process: “civilization is the condition for the downfall of civilization.”) The emergence of globalized anti-belief systems has essentially rendered ideologies as mere pretexts, rationalizations, or hollowed-out excuses. The act of terror becomes the ultimate Selfie. (What did the suicide bomber say the split second after he pushed the detonator? “Look Ma, no hands!”)

The director inserts one showstopper, jaw-dropping “cinematic” moment here, practically an outtake from his dizzyingly accomplished and self-divided Saint Laurent: dissolution blown up to a fragi-comic euphoria, the better to plunge into a reverie of exhaustion and decay. Yacine descends a flight of stairs wearing a ton of lipstick and a goofy grin, breaking out of his shell to lip-synch Shirley Bassey’s grander-than-grandiose “My Way” for his dumbfounded comrades. Parodying, or channeling, the bearded Eurovision singer Conchita Wurst, he provokes delight, discomfort, and amazement. His tour de force is still in progress when there’s a brutal cutaway to the outside of the building and the sound of approaching sirens; then Bonello cuts right back to the brash, gesticulating lad. It’s a history of hubris and folly in less time than it takes to boil an egg.

What’s principally stimulating in Bonello is his basic lack of self-censoring mechanisms, and his fearless leaps from one movie to the next. This cool drink of cyanide comes after the fashion-drunk heights and depths of Saint Laurent; before that came a period prostitution piece (House of Tolerance, 2011) and the Rivette-ing descent into the idea of pleasure-as- battlefield in On War (2008, a fox/rabbit-hole of a film muddily mucking about with cults, sex, death, aborted rebirth, and Mathieu Amalric reenacting Apocalypse Now all by his lonesome). That in turn followed Tiresia (2003), a film that took the notion of the aesthete as mythopoeic figure about as far as you could this side of the unrecorded Jerry Lewis/Jean Cocteau collaboration, The Day the Poet Cried. Which in some tortured way had sprung from the head of The Pornographer (2001), with Jean-Pierre Léaud phenomenal as the title auteur, occupying a charmed, magnetic marginality somewhere between shaman and rank hack.

House of Tolerance houses the most Bonello paradoxes: using a fin de siècle brothel as an all-purpose canvas, it evolves from a beautiful compendium of painting-like shots and exquisitely dishabille prostitutes-as-artist’s-models (cf. Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, Munch), passing through a primer on the brothel as enterprise and institution, into a last dance with ravage and ruin. It arrives at the intellectual equivalent of one of those John Woo standoffs—except instead of guns-at-heads, think Flowers of Shanghai wielded by Buñuel, with art, commerce, sexual exploitation, and bourgeois hypocrisy all facing off in a thorny, unresolved bouquet. Nocturama skirts the same biting-off-more-than-it-can-digest overload, but the difference is that he doesn’t shape its characters, or rather “types,” along such familiarly rounded lines and emotional beats. Bonello’s one-from-Fifth-Column-A, one-from-Fifth-Column-B (-C-D-Etc.) approach emphasizes their narrow delusionality: they’re as much revolutionaries as a “kept woman” is “independent.”

Not a lot of working directors have found as many ways to break the cycle of comfortable self-congratulation and cultivated, custom-fitted seriousness. Bonello gives the impression of a solid, eccentric carpenter who never wants to raze the same façade twice, and takes the greatest satisfaction in dumping ice water on the righteous, the pursed-lipped, and the lachrymose. He’s always at his best invoking cosseted worlds plastered with posters, to-do-hickeys, speechless refuseniks, semi-conscious activities, blind-leading-blind-proclivities, mummified corpses, and brand recognition: if you can watch Saint Laurent and not be reminded of both Saint Warhol and Saint Godard as fellow players in the brand-name game, then you may just be a candidate for his next edition of the Champagne Bucket Challenge. Sometimes recalcitrant as director, Bonello breaks up monotony and portentousness with an unexpected cut or framing device or movement (a slow pan that speeds up suddenly, or a character—“I’m giving up. Everyone makes films”—taking a pratfall while making a decisive exit).

The more you engage with Bonello’s swirl of abstract unease and close-in observation, the more that tension is defined as a sense of far-flung doubt, absurdity, second thoughts, anxieties of impotence, incapacity, fraud, and denial. Fashion and art exist in a weird orbit of distance and envy, gravity and ephemerality. Radical chic has been a dependable organizing principle of postmodern consciousness: throw in post-politics and random terror and the mix becomes more piercing, dissatisfying, and destabilizing. Yet still stuck between a past that isn’t what it used to be and a future that’s shaping up like a bad reboot of every pissant dystopian disasterdrome of the past 50 years, he doesn’t offer any airtight escape hatch: decay is programmed into the sublime.

Nocturama taps into something topsy-turvy that has been gaining traction in the world since before the turn of the century. Bits and pieces, little premonitions or preparations, have been scattered throughout Bonello’s movies. On War’s coffin showroom scene was one; that film’s psychodrama war games and conspiratorial shadow society might be a sketch for the insensible actions of Nocturama’s toy soldiers. (And the scene where the police race past Amalric’s Bertrand on their way to an undisclosed emergency feels like a dry run.) Affluence and excess in Saint Laurent ping-ponged off “current events”—the uprisings of May ’68 split-screened with runway models, or when the Baader-Meinhof Group’s capture provokes Yves’s lover to suggest throwing a solidarity party. As far back as The Pornographer, Bonello shows a slap-hapless bunch of second-string radicals groping to reconstitute the revolution—with silence as their manifesto. Better mimes than bombs (or for that matter, memes), but another cause that was lost before it even began.

Bonello’s work has struggled with how to break through from the cordoned-off realm of art into a meaningful way of life. The elusive road to transcendence is booby-trapped with so many improvised explosive devices, and the best-laid fantasies or dreamlands can go wildly, bleakly awry. It would be tragic, really, if it weren’t so gravely and calmly absurd. His overarching theme—or less grandly and more precisely, intuition—is of how the prospect of revolution gave way to a devastating, culture-wide devolution. His penchant for the dynamics involved in the attraction of opposites (creativity vs. creative self-destruction) serves Nocturama well: the spectacle of ideas and passions wearing or burning out, reduced to rhetorical gestures, diminishing returns, media Optics, and weaponized banality. In light of the film’s implications, I can visualize Kendall Jenner switching from Pepsi spokesmodel to ISIS recruiter—swapping one social spectacle for the other.

There is no turning back the clock, no resurrecting the Paris Commune as a pop-up War-Front. The bridges to or from 1968’s collective experiment/delirium have all been burned. Imagination may not be dead but it’s losing a lot of blood. Which way is up, or forward? Unintended consequences are the one sure thing going—and if movies have anything at all to teach us, it’s how tangled, ambivalent, contradictory, and conflicted people’s motives, desires, and intentions can be.

For epigones of division and destruction, it’s all a game of Terror Roulette: spin the violence wheel and watch what happens. In a society at the end of its collective rope or on the verge of a mass nervous breakdown, it hardly matters whether Neoliberalism, modernity, secular depravity, or multiculturalism is the target. The movie’s inadvertent kamikazes realize far too late that there’s no win-win for them here, not even a funeral-pyrrhic victory. The only thing that’s left is to set in motion a string of calamities that will culminate in a global “lose-lose” result.

Somehow the road from Weekend père led to the drab-bag doorstep of a Young Adult world, watching infantilized gamers of all ages play at “deconstructing the administrative state” or take up “Resistance” (complete with fashion-statement hats—way niftier than that darn prole cap of Lenin’s!). There’s a big question Bonello’s too tactful (not wanting to bruise the feelings of his financiers, I’m sure) to address, though it’s surely implicit in every frame of the final reel right down to the “Help me” cry over the interjected flames. Namely, on the international Terror Roulette wheel, how soon until bombers of whatever yellow stripe—Islamist, Hindi, far-leftist, alt-rightist—pick a movie theater for their next venue? Maybe even one, you know, showing Nocturama. Then this film will have given a truly new meaning to the term, “Target Demographic.”

Closer Look: Nocturama is opening in the summer.

Howard Hampton frequently writes about organized chaos for Film Comment.