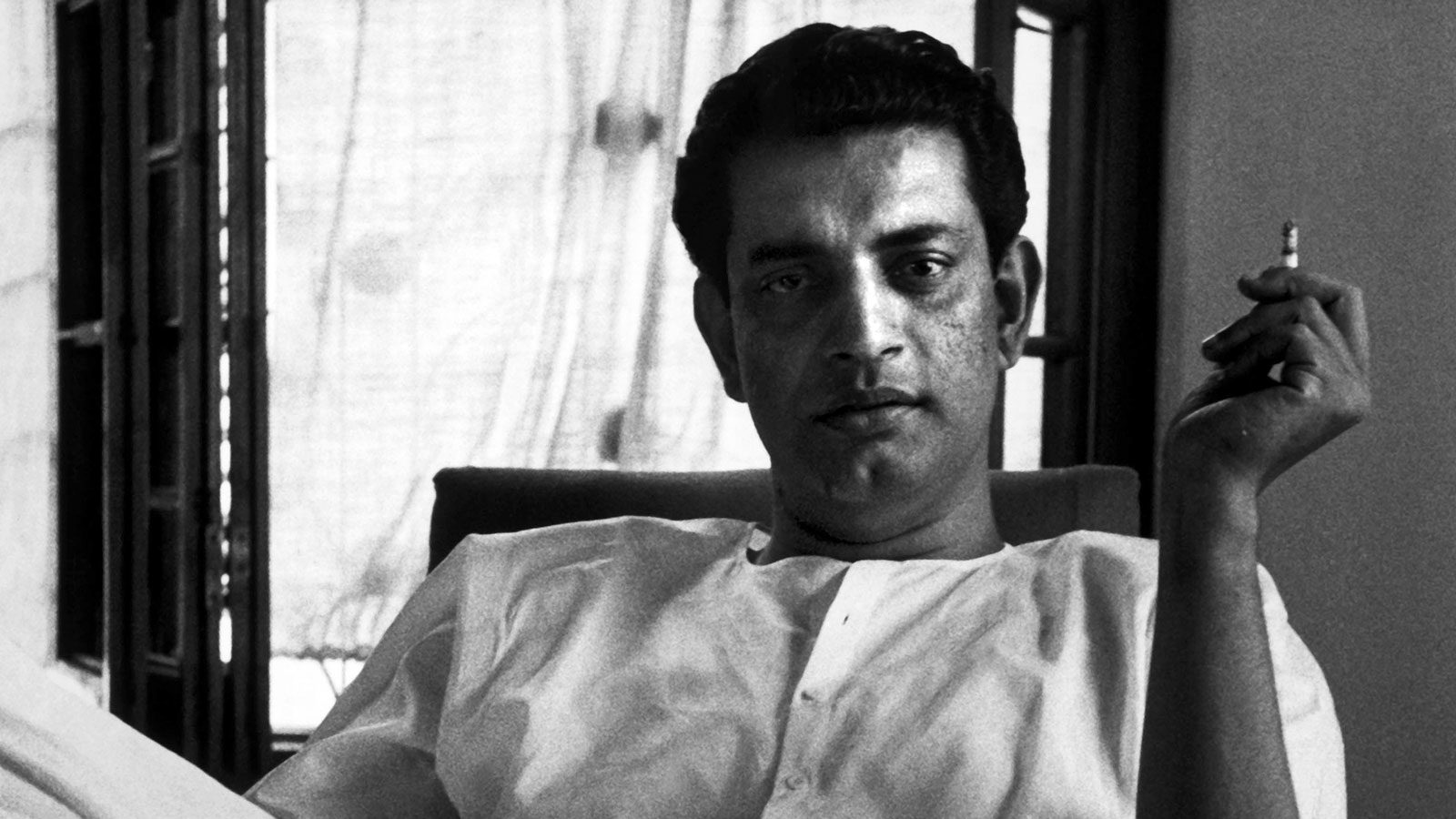

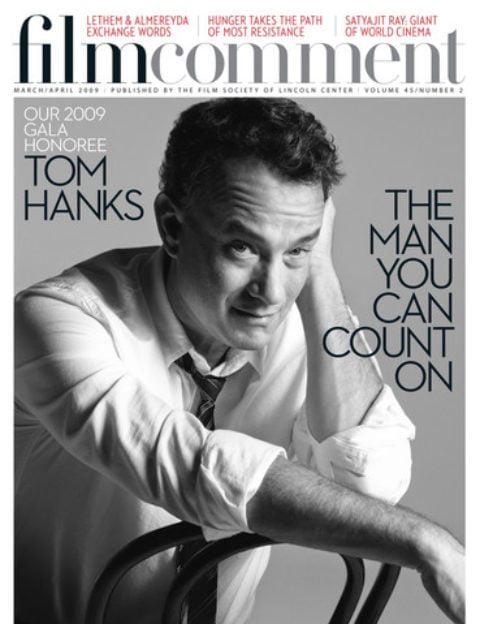

By Nicolas Rapold in the March-April 2009 Issue

Master of the House

A giant of world cinema’s golden age, Satyajit Ray held up a mirror to Bengal’s middle class

Before he hit the ground running in 1955 with Pather Panchali, Satyajit Ray made his living designing tea-biscuit wrappers and bookjackets. When he turned to filmmaking, he also fashioned his own posters, but his general knack for prefatory visuals shined in his eloquent credit sequences. The best—a prologue in miniature—precedes The Music Room (58), a study in noble folly about a fading zamindar in Thirties Bengal. A slow zoom takes in a lustrous chandelier suspended in a void, accompanied on the soundtrack by a virtuosic instrumental drone. Eye and ear are mesmerized, yet the lush baroque texture evokes decay—the perfect overture to the film’s spectacle of an aristocrat bankrupting himself through his overindulgence in private chamber concerts.

From the March-April 2009 Issue

Also in this issue

The Music Room came as a necessary deep breath after the success of Pather Panchali (aka Song of the Little Road). Ray had first encountered Bibhutibhushan Banerjee’s Apu novels when he was assigned them to design in the Forties, and the result was an almost cosmically timely debut. Echoing the éclat of Rashomon a few years earlier, Pather Panchali represented the triumphant discovery of another cinema and with its rural village setting, another world. Critics agreed: here was India’s Renoir and Bengal’s neorealist counterpart. In retrospect, as a cinephile and a well-developed independent talent with no professional apprenticeship, he even seemed to anticipate the French New Wave. Tags were affixed—“humanist” above all, “lyrical,” “Chekhovian”—and another giant was bagged for the canon. (“The kind of statement you come across is: Satyajit Ray is Chekhovian. Nothing more than that, there’s no actual elaborating on that statement,” Ray sighed in a 1972 interview.)

Per one Indian critic, writing shortly after Ray’s death in 1992, the wide-eyed praise evinced a bit of “orientalist phantasy,” especially given Pather Panchali’s unreconstructed village setting. It could be forgotten that Apu and his sister were played by Calcutta students, that the brokebacked toothless Auntie was a veteran stage actress, or that the film’s sense of authenticity derived from Banerjee’s firsthand experiences, not Ray’s. If any standard rap—or wrapper—on Ray has obscured the work itself, it might be the claim of universalism, as if Apu were simply Antoine Doinel avant la lettre. Yet, for one thing, as others have also observed, the domestic dramas that dominate his oeuvre are rooted in the specific struggles of the middle class at various stages in post-Independence India’s development. And, moreover, countless cultural details, especially in Ray’s often exacting production design and profuse textual quotation, are lost on most Western viewers. (A panchali, for example, is a genre of popular scripture, read musically by rural women not unlike Apu’s mother; as for the credits of Pather, they imitate ancient calligraphic script, handwritten by Ray on coarse paper.)

The World of Apu

But beyond that, a pattern emerges that’s as stark as the qualities that have led to the now clichéd label of humanism: in film after film he presents a series of contemplative intellectuals and aesthetes who stubbornly follow a different path, or simply waver. Their behavior often clashes with practical realities, and Ray is invested in observing the tensions caused by their ideals as well as the pleasures they afford. The tendency starts with Apu’s father, a poor brahmin who’s cheerfully insouciant about pressing a local landowner for his wages, even as his wife frets about money and maintaining a modicum of self-respect. “Who cares? I’m a poet and a playwright,” he says with a smile. He schools young Apu in reading and writing, and the guava does not fall far from the tree: in Aparajito (56), the boy’s smarts land him a scholarship in Calcutta after his father dies, and at the start of The World of Apu (59), our hero—well-educated, unemployed, and writing a novel—is sidetracking his landlord with bon mots. Later, like a character written into a new plot, the rootless Apu unexpectedly marries a friend’s cousin (Sharmila Tagore) when her intended groom proves to be insane. When she dies in childbirth, Apu exiles himself and leaves the child to relatives. Only later, after an almost mystical scene in which he scatters the pages of his autobiographical novel into a ravine, does he work his way around to accepting fatherhood and life in general.

The little detail of Apu’s learning to read from his father must have held special charm for Ray, himself the descendant of a line of versatile artists. His father was a beloved writer of nonsense rhymes, an illustrator, and innovative printer; he died when Ray was two. Equally gifted, his grandfather wrote music, and launched a printing press and a children’s magazine, Sandesh, which Ray would revive in 1961. In that same year, the filmmaker started composing his own scores. The overwhelming majority of his scripts were literary adaptations, many of them from works by Rabindranath Tagore. The multitalented Ray family, like the influential Tagore clan, was in the spirit of the 19th-century Bengali renaissance, a period of East-West cultural ferment spurred by the emergence of a burgeoning educated class.

One of Ray’s best films, Charulata (64), is set during this era, circa 1880, in a well-appointed house (featuring a printing press under the same roof, as in Ray’s childhood home). In an atmosphere of oppressive languor, young literary-minded Charu (Madhabi Mukherjee) idles away without children, her affectionate husband nonetheless occupied with publishing a political newspaper downstairs. (Credit sequence: Charu embroidering in close-up, stitch by painstaking stitch.) The husband invites his poet younger cousin Amal (Soumitra Chatterjee, who played the adult Apu) to stay, and Ray sets into motion a volatile pair-up: the mutual attraction of two like-minded restless spirits, one bound by marriage and gender, the other sympathetic but feeling the guilt of a devoted relative.

Charulata

Ray’s feel for domestic spaces creates a housebound lyricism. Charu languishes in the grand bedroom, down a portico, and in the garden out back, agonizing over the to-and-froing Amal, who playfully recites poetry. A game of cards with another in-law, lazing on a great Victorian four-poster, trails away in torpor. All Ray’s films bear the sensitive ear of a composer; his indoor scenes are usually filled out by the living color of someone chanting outside or the sound of traffic. Here, Charu keenly attends to the sound of drumming in the street, then picks out its source with her opera glasses. On the structural level, Ray’s comment to Georges Sadoul—“I thought endlessly of Mozart while making the film”—underlines the alchemical, shifting movement between Charu and Amal’s literary and amorous passions. In a final series of freeze-frames, husband and wife are transfixed on the brink of joining hands and reconciling, as the Bengali script of the words “The Broken Nest”—the title of Rabindranath Tagore’s source novel—appears on screen.

Ray worked repeatedly with certain actors, and partly attributed his annual output in the Sixties to a desire to keep his crew together. Although Mukherjee worked for Ray less frequently than Tagore, all her performances are memorable. In The Big City (63), as a Calcutta housewife who starts selling appliances door to door to support her cozy, thrifty household, Mukherjee contributes another portrait of a woman finding fulfillment outside traditional roles (and outside the house), with the intriguing foil of a mixed-race co-worker who is snubbed by their Bengali boss. The wife’s newfound avidity (“I don’t feel tired even after working all day!”) ruffles her clerk husband, but Ray closes on a note of optimism for this modern, urban family who are making do in novel ways.

That forward-looking conclusion is a characteristic strength of Ray’s best dramas: impasses become plausible opportunities for reinvention. But it’s by no means the rule, and he can wring just as much impact out of endings that leave characters one note short of resolution. In “The Postmaster,” the first tale in his triptych Teen Kanya (61), a Calcuttan (Anil Chatterjee) becomes the one-man post office in a village and idly takes his wispy servant girl under his wing, but after a bout of malaria, hurriedly resigns. Hurt, the girl walks on by when he offers her cash as he departs, to his crestfallen surprise. Likewise, in The Coward (65), yet another urbanite (a screenwriter no less, played by Soumitra Chatterjee) crashes with a tea planter when his car breaks down—only to learn that the loudmouth’s wife is his ex-girlfriend (Mukherjee). This twist on Ray’s wandering outsider motif—the commitment-averse artist losing his university sweetheart to a businessman—spirals into flashback-ridden obsessive regret and ends with the protagonist receiving a parting passive-aggressive jab from her at the train station.

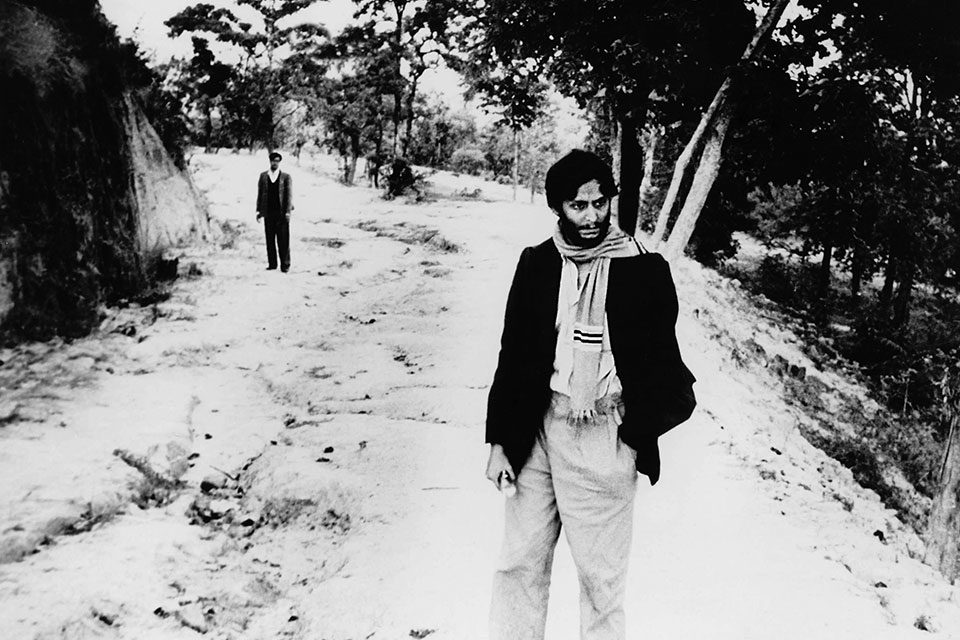

The Adversary

Against the backdrop of a nation maturing after the zero hour of independence in 1947, generational tensions are another concern of Ray’s. Two minor characters in The Big City respectively embody forward-looking self-sufficiency and the burden of historical debt: Mukherjee’s studious, spunky daughter will no doubt follow her mother’s lead with gusto, whereas her lottery-playing grandfather is a retired schoolteacher who cadges freebies from his former students, now doctors and lawyers. Ray also refracted his sociopolitical surroundings through the viewpoints of young, capable men finding their feet. The big city revisited, The Middleman (75) presents curdled dreams of success to convey Ray’s disgust with corruption (the film opened the same year Prime Minister Indira Gandhi exercised new powers by decree under the State of Emergency). A fresh graduate—the only one in an opening examination sequence who isn’t flagrantly cheating—gives up on further study to enter the shady trade of brokering goods. The story spirals queasily down streets plastered with signs and graffiti, as the beginner businessman is ensnared by a sleazy middleman/procurer, leading to one of Ray’s strangest tableaus: a kindly mother pimping for her daughters in a living room overlooked by a huge photo of puppies.

In The Adversary (70), Ray’s predilection for stalled intellectuals leads to a familiar-feeling portrait of restive alienation. The discontent of young, brooding-browed Siddhartha (Dhritiman Chatterjee), who quits med school when his father dies, supplies the impetus for this partly subjective, dilatory film, which is punctuated with flashbacks to an idealized childhood. The father’s death, which opens the film, is visualized in negative; at the end, an infernal wait for a job interview triggers a fantasy of the room lined with skeletons. Ray is less persuasive, perhaps less comfortable here, but Siddhartha’s nostalgic leanings and protectiveness toward his liberated sister and bomb-thrower brother do suggest the director’s attachment to prerogatives and tradition at a time of personal and political strife. True to his classicist cast, Ray mainly reaches for obtrusive flourishes to convey psychological distress, with often schematic results. The Hero (66) gave a cresting movie star (played by big-name Bengali actor Uttam Kumar) similar flashbacks and even a skeleton vision, but to less effect than, say, the resourceful mise en scène of Days and Nights in the Forest (69), about a country jaunt by four young cityfolk.

Engagé critics wished that Ray would adopt more “committed” politics, presumably implying that he wasn’t filming enough Marxist ferment, but he did not avoid difficult subjects. Distant Thunder (73), part of a loose political trilogy with The Adversary and Company Limited (71), revisited the village setting of the Apu saga under grim wartime circumstances: the Bengal famine of 1943 amidst food rationing by the British Army. Here the domestic struggles and diminished status of Ray’s rural brahmin protagonist are used to underline the social upheaval that comes in the wake of catastrophe. Nature’s beauty—trees, lilies, butterflies, filmed in robust color—becomes jarring; the lake where his vivacious wife formerly delighted in swimming is now trawled for pond snails by desperate villagers. Marred by a subplot about a scarred kiln owner offering sex in exchange for rice, the film ends on a rousing, magazine-ready picture of the Indian nation as a united family, framed in silhouette against the horizon.

The Chess Players

But in some ways Ray’s boldest work came much earlier, in the full flush of his new prestige, with the uncanny Devi (60), set in 1860 and far ahead of its own time. Thirteen-year-old Sharmila Tagore (Apu’s wife one year earlier) plays Doyamoyee, a girl whose father decides she is the incarnation of Kali. Almost overnight her role switches from happily doting daughter to an idol mobbed by worshippers, beset by the clamor of bells and chanting. Ray lays bare a practice of hysterical religious veneration, and focuses on Tagore’s dismal, demure expressions, capturing her alarm over this attention and her panic at effectively “disappearing” as a human being. (He gets at similar feelings of entrapment in the tomboy married off in “Samapti” from the Teen Kanya tales.) With prolonged close-ups Ray also subtly questions the metaphysics of apprehending the divine. As for Doyamoyee, she goes mad, fleeing her recently returned university-educated husband (and everyone else) and vanishing into the misty countryside, traversing the frame diagonally in one of Ray’s most striking shots.

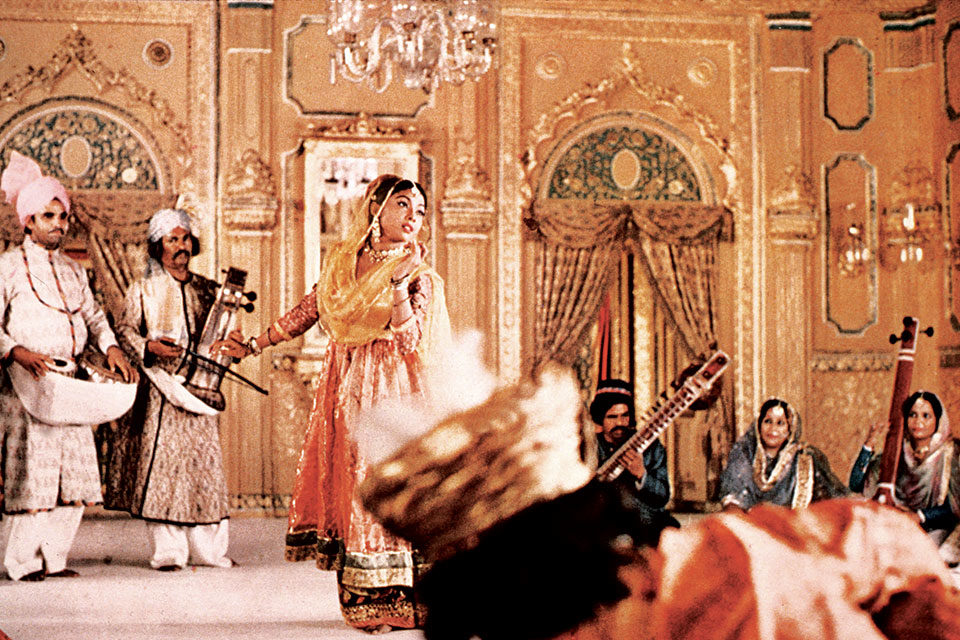

The glorious color production The Chess Players (77), the director’s most expensive and his first in Hindi and Urdu, is also set in the mid-19th century, but Ray brings a kinder eye to the obsessions on display. Two tales run in gently ironic parallel: British General Outram (Richard Attenborough) schemes to annex the kingdom of terminal aesthete Wajid Ali Shah (Amjad Khan); meanwhile, two Lucknowi landowners (Sanjeev Kumar and Saeed Jaffrey) become addicted to chess. Rejected by many Indian distributors, this strange affair, like an Oliveira elegy on civilization, grants the full nobility and blithe aestheticism of the cultured, effeminate Wajid, with cutaways to the charmingly single-minded chess players, who strategize in microcosm as their society changes around them. At a moment when he preferred disengagement from the present, Ray followed up with The Elephant God (78), a playful mystery featuring the hero of a series of detective novels he had written since 1965. (Ray was also beloved as a children’s author and illustrator in India, and his 1968 musical adventure The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha, replete with multitiered dance routines, enjoyed great popularity.)

Thirty-five years after Pather Panchali, Ray made his final film, The Stranger (91), about a forgotten uncle who reappears after 35 years of travels in the West. He is enigmatic and playfully polemical, and his niece’s husband suspects he is a fraud; in their conversation he defends his open-minded, world-embracing views and his admiration for unmodernized “tribals.” At the end, when the matter of a family inheritance comes to a head, it emerges that it is the family that is being tested, not the prodigal uncle. Somewhere between a stock eccentric in a children’s book and a walking artistic valediction, here is Ray’s perennial thoughtful protagonist allowed to live his entire life without the hard turn toward practicality. Rather than becoming a man set adrift, he perhaps embodies Ray’s own serene perception: “You don’t have to show many things in a film,” Ray once said, quoted his critical touchstone Renoir, “but you have to be very careful to show only the right things.” More often than not, Ray did just that.