By Eric Hynes in the May-June 2017 Issue

Make It Real: Living Proof

Melding screening and performance, filmmakers like Travis Wilkerson search for new paths to intimacy and spontaneity

The director introduces the film as the director often does, keeping the preamble to a minimum before slinking away. The lights go down. The screen fires up. And then the director comes right back out again, sitting at a desk a few feet from where he’d just addressed the audience. And he stays there, minimally lit and intermittently vocal, but always visible. He’s part of the show, a live three-dimensional stage presence accompanying the recorded, two-dimensional images projected behind.

From the May-June 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

When Travis Wilkerson presented Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun? at Sundance in January and True/False in March, his live theatrical show was anomalous among a slate of prerecorded documentaries. Yet it’s part of a tradition of live screenings that stretches back to the origins of cinema, when the mechanical act of projection was conspicuously present and clamorously audible, and the film space itself was a vestige of, if not synonymous with, the theater. In a cinema, screenings tacitly take place in the present tense of the screening room, while the spectator is persuaded into the space and time of the projected image. But there are also cinematic events in which the room and the present moment are emphasized, and in which the projected image is a component feature rather than the sole transporting focus of a live piece.

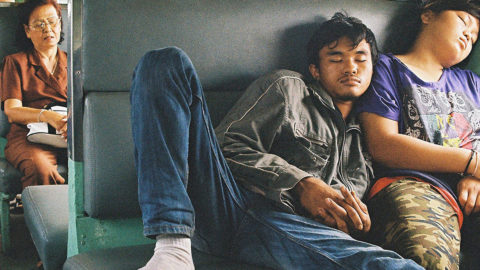

Wilkerson is among several artists creating works for the live realm that incorporate or intersect with documentary, a hybridized practice that itself elasticizes between intimacy and distance, lecture-like presentation and confessional multimedia monologue. Also at Sundance this year, Terence Nance debuted a two-part piece extraordinarily entitled 18 Black Girls/Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the Singularity and Are Thus Spiritual Machines: $X in an Edition of $97 Quadrillion, in which the director didn’t give a speaking performance but rather conducted live Google searches of “one-year-old black boy,” “two-year-old black boy,” and so on, clicking through results until age 18, before reprising the endeavor for “girl” searches. As with strictly cinematic nonfiction, there’s a base-level engagement with factual reality in these theatrical pieces, after which anything goes.

18 Black Girls/Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the Singularity and Are Thus Spiritual Machines: $X in an Edition of $97 Quadrillion

Befitting the inherent ambiguities of such a presentation, in terms of form, time tense, and audience orientation, Wilkerson’s latest piece manages to be both inward and outward facing, intensely reflective and intently performed. The piece sees the leftist, socially progressive filmmaker (An Injury to One, Machine Gun or Typewriter?) interrogating the troubling strain of racism in his own family history. He quickly sets sights on his late maternal great-grandfather, S.E. Branch, who ran a general store in Alabama, and once shot and killed a supposed intruder, a local black man named Bill Spann. Wilkerson dually investigates the details of the killing and the backstories of his relatives—none of it very pretty—motivated by both a detective’s tenacity and a white man’s wholly justified guilt. Long stretches of the work are entirely screen-based, with audio from talking-head interviews silencing the onstage director for extended periods, while at other times brief extant 8mm clips of Branch are replayed over and over, each repetition another underline beneath Wilkerson’s angered and mortified text.

One can imagine a prerecorded version of the piece, since image, music, and voiceover text are precisely cued and synced throughout (i.e., it’s well-edited). Indeed, Wilkerson’s physical presence seems less crucial to the form of the piece than to the spirit of it. More than a mining of the director’s ugly family history, it’s closer to a public exorcism, in which Wilkerson personally owns up to the sins of his kin while symbolically standing in for the sins of his country and race. Formally, the live component might be elective; morally, it’s essential.

Wilkerson’s grave, oft-seething stage manner contrasts with that of Sam Green, a well-traveled live documentary practitioner who takes a more conversational and ingratiating tack. Like Wilkerson’s, much of Green’s work invites the audience into his process, leading us into archival searches and down frustrating and fascinating dead ends. Yet his are less evidentiary investigations than collaborative research projects—curious flips through old telephone books, left turns into Americana. While Green has also made traditional documentaries (The Weather Underground), his stage work exhibits a dexterous commitment to a third dimension. His manner, tone, and rhetorical tendencies summon radio storytellers, while his visualizations shift from sidecar (photographs and slides) to driver’s seat (clips, scenes, full-audio interviews). There’s also a live music component, which was in full effect at a recent series of shows co-hosted by his musician/animator/filmmaker brother Brent Green at Brooklyn Academy of Music. Though everything’s been composed, practiced, and refined, there’s a pleasingly imperfect quality to the act, with rough edges of Green’s spoken words brushing against his images, and a band of musicians both responding to and propelling him in turn.

Sam Green performance

Considering their theatricality, it’s hard to imagine Green’s pieces working as prerecorded shorts (he’s refrained from producing any, and even from recording his live act). His piece on Louis Armstrong’s private tapes, which he did as a TED Talk in 2015, is so good it could probably work in any form, and yet its climax crucially involves the becalmed director persuading spectators to transport themselves across space and time to join a drunk and sated Armstrong in the wee small hours of a private evening. Collectively willful displacement is the key. Deeper meaning gets catalyzed in the spectator.

It’s as if a documentary had been pulled apart and is being re-synced for us in the room, except there’s no original document to dismantle, no original film to remix as theater. These documentaries are in their native, if unconventional state. In addition to being a collaborating player, Green’s band is a synecdoche for how these various elements make music together. Individually they’re fine, but the art, and its value as documentary, activates when they’re in concert with each other and the audience.

Live music plays an even more crucial role in Jem Cohen’s theatrical experimentations, which have been an ongoing sideline for the director of Instrument and Museum Hours for many years. At a recent show of short films at 22 Boerum Place in Brooklyn, a majestically non-renovated, high-vaulted-ceilinged venue for the arts organization Issue Project Room, Cohen systematically treated sound and picture as elements with unstable, even inverse associations. An outfit comprised of guitarist Guy Picciotto, lutist George Xylouris, and drummer Jim White stood to the left of a large screen faced by spectators haphazardly clustered in folding chairs. The first short, comprised of decades-old 8mm footage of Coney Island edited in-camera, was presented without sound, while the second, a deadpan set of impressions recorded this past January at the Presidential inauguration in D.C., introduced scant live music to prerecorded sound. Ensuing pieces pursued different dynamics between picture and music—from aggressive to recessive scoring, supportive and contrapuntal—as the shorts, most made specifically for this live format, varied from abstracted cityscapes to a surprisingly ominous family film. A final section removed moving images entirely so that only music remained.

Cohen doesn’t front for his work the way green and Wilkerson do, instead choosing to manipulate sound levels from the back of the room. Thus the show more closely evoked, depending on the piece, early silent cinema presentations or rock ’n’ roll stage projections (a form Cohen knows well from collaborations with R.E.M. and Fugazi). Yet the entire design of the evening evidenced his probing artistry, as the films pushed music into unexpected places, and both music and film thwarted passive receptivity in the audience. While non-narrative, the footage was all snatched from unscripted life, and presented in an analogously unscripted, and similarly semi-controlled, setting.

For that final, film-free song, a single light shone behind and from below the musicians. With chairs all facing front, you had to rotate your head back, and accept the gaze of the rest of the room, to even notice that dramatic, elongated shadows of the trio danced against the high ceiling of the room. Suddenly it was a pre-cinematic shadow play, cast not against a screen but across peeling paint and a chandelier high above, an elemental visual creation for which there would be no record, no playback. Toggling between physical forms and their shadows cast above, a film developed in your head—edited in-camera, as it were—leaving one mindful of others authoring their own. Something real was happening in the room, and it required no less than the full room, with its sounds, images, architectural dimensions, and mindfully empowered spectators, to achieve the art, and fully realize the moment.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and associate film curator at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.