By Harlan Jacobson in the September-October 1988 Issue

Interview: Martin Scorsese

The director on his passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ

Two guys, tough guys, sit in the waiting room of Martin Scorsese’s Manhattan offices. Are they auditioning for Scorsese’s forthcoming Mafia movie? Are they a pair of Willem Dafoe’s roustabout apostles? No. They are not even waiting to see the director of The Last Temptation of Christ. They are waiting to see anyone who wants to see Scorsese. Lew Wasserman may have been depicted as a Christ killer, but his company only distributes the movie. Scorsese made it. And have people made threats? In a generous, full-disclosure interview of more than two hours, this is the one question he is reluctant to answer. “Well, let’s say there are a lot of people around. Privacy is gone, and everyone is very careful.”

From the September-October 1988 Issue

Also in this issue

Very careful, and very open. Those attitudes marked both Scorsese’s ballsy adaptation of the Nikos Kazantzakis novel and his conversation with me, a week after The Last Temptation’s opening. ABC News’s Person of the Week was happy to discuss the film with someone who had logged as much time with the priests and nuns as he had. And to explain how personal and universal—how, even, paramount—was his quest to make this picture.

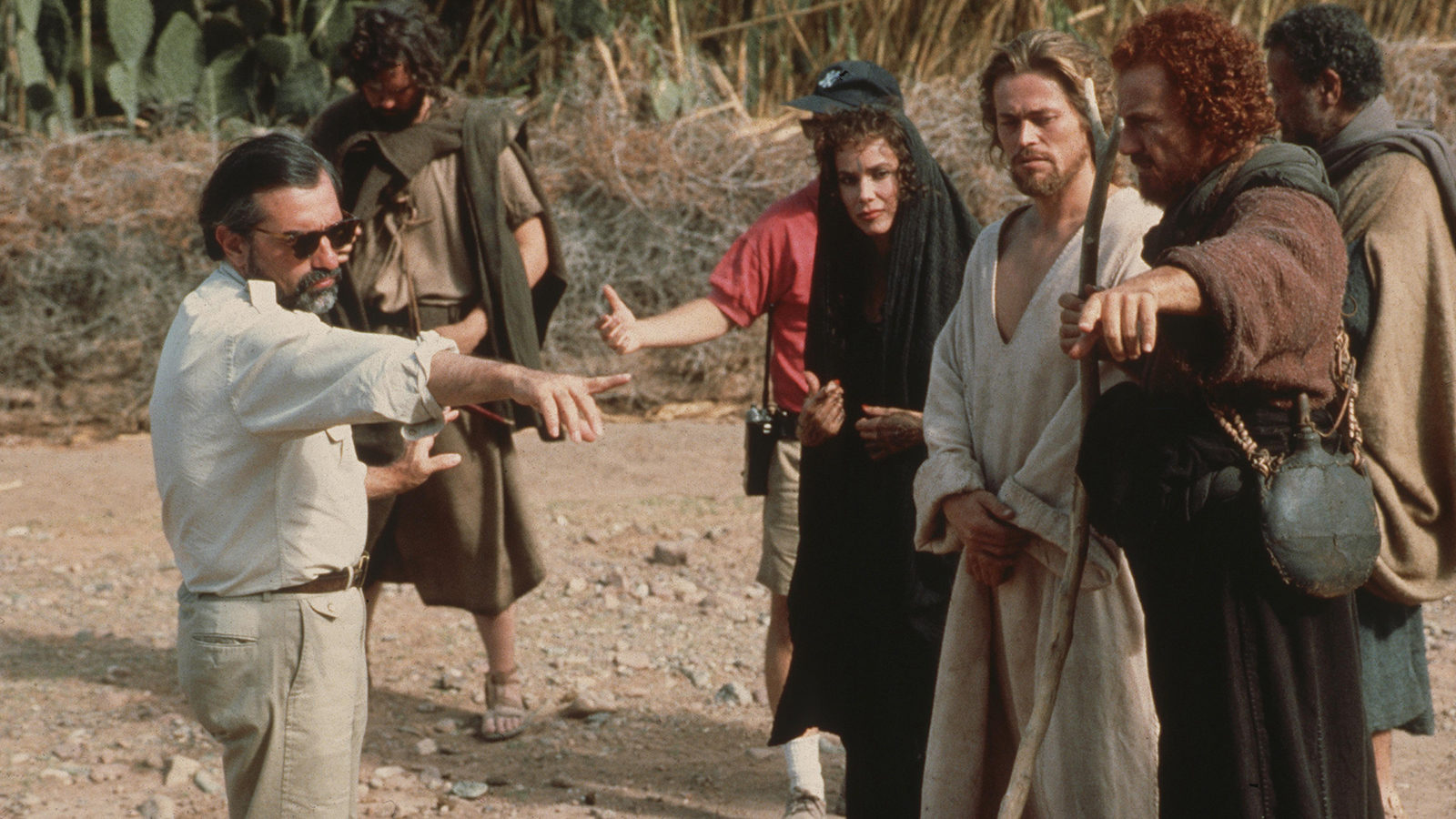

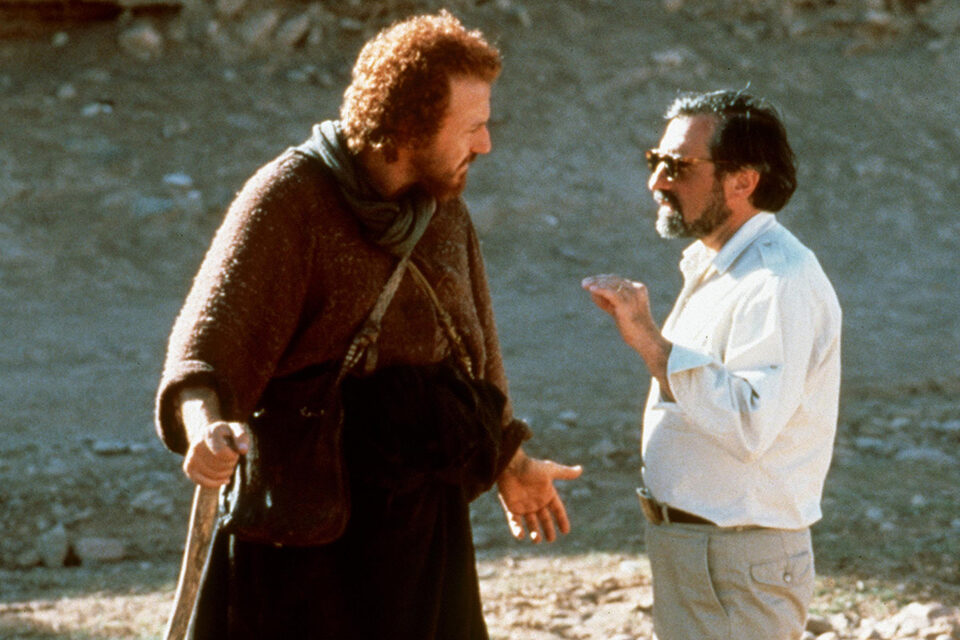

Harvey Keitel and Martin Scorsese on the set of The Last Temptation Of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988)

Was your family religious?

My parents grew up Americans, Italian-Americans. Their idea was survival; my father went to work when he was nine years old; there was hardly room to sleep; you had to fight, you literally had to fight with your brothers and sisters for food and attention; if you got into trouble, you had to know enough to stay on the streets for two nights. It was survival. And I don’t think the church figured into their life that much. Italian-Italian Catholics, like my assistant Rafael Donato, who says, “We’re really pagans. Pagans in the good sense. We enjoy life, we put the church in a certain perspective.” My parents were able to do that. When the church wanted to delve into personal lives, how many children they should have, my parents shied away from that. They figured that wasn’t any of the priest’s business. I was the one who took the church seriously. My grandmother was the one who had the pOrtrait of the Sacred Heart. Also the niche with the statue of the Virgin Mary grinding the snake under her foot. Also the beautiful, gigantic crucifix over the bed, with Jesus in brass and the palms from Palm Sunday draped over the crossbal: And remember when you’d go into church and you’d see Jesus on the cross? And he’s bleeding from the wound on his side? And there’s this angel below him with a cup? And the blood is dripping into the cup? The most precious blood! A great title for a film: Most Precious Blood.

The scene where Jesus returns from his first temptations in the desert to open his robes and pull out his heart is right from that iconography.

Actually, that scene, which was not in the Kazantzakis book, was written by Paul Schrader, a Dutch Calvinist, and it was kind of nudged to me as Catholic. He also wanted to show that the supematural and the natural exist on the same plane. But we were doing that all along. He wanted to show the angel at the end tuming into a gargoyle, and slithering off a table. I leveled that all out. I wanted it to be like when I was growing up, and my grandparents and parents and aunts would tell me stories—ghost stories—that took place right in our apartment. The supematural and the natural on the same plane. Only here you’re dealing wi th the messiah. So if a snake goes by, the snake is going to talk. In voice over. Don’t even try to do Francis the Talking Mule. Or Leo the Talking Lion. Forget it! It’s Harvey Keitel’s voice, or mine, saying, “Do you recognize me? I’m your heart.”

So when we got to do the Sacred Heart scene, here’s what I thought was more important. You have these guys bickering all the time, just like in the gospels. It’s all there: “I’m the one, I’m the one, I’m gonna sit next to him when the Kingdom of Heaven comes. I’ll be at his right hand.” “No, I’m gonna be at his right hand!” Hysterical sturn So they’re all bickering, and Judas is being a pain, as usual. And then Jesus shows up, and it’s party solidarity. It’s the Democratic convention, everybody getting together. Unity. And it’s his presence is shining so strong at that moment that they have to be unified behind him. Then again, you could say that the apostles are seeing him just back from the desert, with the light from the campfire, and the music around, and the glow behind his head, just a little touch of De Mille. It could be mass hallucination, mass hypnosis. We don’t know. It’s a symbol to bring them all together—especially Judas, who kisses his feet and says, “Adonai!” All of a sudden Jesus is God? Wait a second! Yes—Judas needs this. So do the others, to be convinced that this is the man.

Is this Jesus God, or a man who thinks he’s God?

He’s God. He’s not deluded. I think Kazantzakis thought that, I think the movie says that, and I know I believe that. The beauty of Kazantzakis’ concept is that Jesus has to put up with everything we go through, all the doubts and fears and anger. He made me feel like he’s sinning—but he’s not sinning, he’s just human. As well as divine. And he has to deal with all this double, triple guilt on the cross. That’s the way I directed it, and that’s what I wanted, because my own religious feelings are the same. I do a lot of thinking about it, at lot of questioning, a lot of doubting, and then some good feeling. A lot of good feeling. And then a lot more questioning, thinking, doubting!

This Jesus is also a mortifier of the flesh, like the medieval flagellants and mystics.

I think mortification of the flesh is important. I don’t mean that you have to go around Whipping yourself, but disciplining is important. This kind of movie, on a $6 million budget, that’s a discipline. When you’re in Morocco, and the sun’s going down, and the generator’s breaking, and the actor’s wig is coming off, and you know you don’t have $26 million and the 10,000 extras like Bertolucci—that’s discipline. You design it another kind of way. Except that, as [Cinematographer] Michael Ballhaus would tell me whenever I got depressed, “That’s the way this picture has to be made.”

You know, the Roman soldiers who surround the temple, at the end? Just five. Same five guys. They were also the guys who were rioting when Jesus starts throwing things. And they were the Levites who come down the stairs, and also the guys who go up the stairs against the Levites! Five gvys from Italy. We had twelve uniforms, but we couldn’t afford the other seven stunt men. So it’s a strong punishment.

And the “fantasy” or “hallucination” that Jesus has at the end of the film, it’s really a diabolical temptation?

Exactly. You know, the one sexual thing the priest told Catholic boys they could not be held responsible for was nocturnal emission. It was like an involuntary fantasy. And with Jesus it’s the same thing. How can you hold him responsible for this fantasy? Of course, Catholic boys were taught that, if you entertained fantasy for a while, it became an occasion of sin. That’s another good title for a movie: Occasion of Sin!

The Last Temptation Of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988)

Your apostles, they don’t speak like the holy figures we’ve heard in other biblical epics. They speak like characters from a Martin Scorsese picture.

Schrader said this to me: “Unless you have them speaking in ancient Aramaic with subtitles, whoever stands behind the camera is going to be doing his ’wrong’ idea of the dialogue of the time. You’ll do your wrong idea. I’d do my wrong idea. Twenty years ago George Stevens did his wrong idea.” And he’s right. But I did want to break away from the sound of the old biblical epics, to make the dialogue plainer, more contemporary. That’s mainly what Jay Cocks and I did the last six drafts of the script. We rewrote 80 percent of the dialogue, arguing over every word. Jesus says to Judas, “You have the harder job.” “Job?” Is that the right word, the simplest, the most effective? Make it more immediate, so people have a sense of who these guys were, not out of a book or a painting, but as if they lived and spoke right now.

The accents do that too. The apostles, most of them, were tough guys who worked with their hands. Peter, the fisherman, was like a rough guy from the docks; he had a Brooklyn accent. Vic Argo, who played Peter, would walk around the set with a cigar in his mouth all the time. And when it was time to shoot, he’d say to me, “I have to lose the cigar, right?”

And the bad guys, Satan and the Romans, they have British accents.

Anyone from the outside is going to sound different. And anyone in authority should have a British accent. It sounds authoritative to American ears. Just as any British actor is supposed to be better than any American actor. Don’t they tend to win the Oscars, just for sounding British? I love British actors, and I love American actors, but there’s a reverse-snobbism thing there. Also, the British empire was a lot like the Roman empire. They occupied America, and a lot of other places, just like the Romans occupied Judaea.

When people in theaters hear these accents, do they giggle at the wrong time?

Some critics called the movie unintentionally funny, but Jay and I don’t think so. Sometimes what’s said is serious, sometimes it’s ironic, and sometimes it’s meant to be funny. One of the elements we kept from the book is that Lazarus never quite heals properly. I mean, the guy’s been dead for three days. Forget it, he’s a little dull! That’s why Harry Dean Stanton [Saul] says, “How’re ya feelin’?” It’s all done with a sense of humor. And if you see it with an audience, they’re going with it. They’re laughing hysterically at the cast-the-first-stone scene with Zebbedee, where Jesus says, ’’Take this rock—mine’s bigger.” An audience picks up on it. They pick up on it as a story. As a movie.

Jay Cocks went to the first public showing at the Ziegfeld in New York, and there were two black ladies behind him saying, “Hallelujah!” and ’’That’s the way He said it!” And when the last temptation comes on, they say, “Oh my God, no! No!” And when he gets back on the cross: “It was a dream! It was a dream!” Which is exactly the way it should be.

The film has certainly made a lot of people think, for the first time in a long time, about Jesus and his message of love. You didn’t mean to be, primarily, a bringer of the Word.

No, but I’ve always taken that word—the idea of love—very seriously. It may not be a stylish thing these days to say you’re a believer, especially to say it so often in the papers, as I’ve been saying it. But I really think Jesus had the right idea. I don’t know how you do it. I guess it has to start with you, and then your children, your wife, your parents, friends, business associates—you start branching out a little bit, it starts to spread, until you create a kind of conglomerate of love. But it’s hard. That’s why Judas’ line in the movie gets a great laugh: “The other day you said, ’A man slaps you, tum the other cheek.’ I don’t like that!” Who does!? We agree with you, Judas. How do you do it?

The Last Temptation Of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988)

Barbara Hershey, who plays Magdalene, gave you a copy of The Last Temptation of Christ in 1972. Did you read it then and know immediately you wanted to make a movie of it?

No! It took me six years to finish it! I’d pick it up, put it down, reread it, be enveloped by the beautiful language of it, then realize I couldn’t shoot the language. I read most of if after Taxi Driver [in 1976] and then finished it while I was visiting the Taviani Brothers on the set of The Meadow in October 1978. And that’s when I realized that this was for me. I’d often thought about doing a documentary on the Gospel—but Pasolini did that.

Paul wrote two drafts of the script, and Paramount backed us. Boris Leven, the production designer, made a trip to Morocco and Israel, scouting locations, working out a look for the film—all those arches!—and making beautiful sketches. It was great, because he was one of the first people who made me conscious of design in films when I was a kid. My family didn’t go to the theater, so I’d never seen theater design. Then I saw The Silver Chalice in 1954, and it was the first time I’d seen a movie presentation of theatrical design, something that wasn’t supposed to be quite real. I’d seen movies with dream sequences, but nothing like this, where the whole film was done in an obvious style. And here we were 30 years later making another biblical epic. It’s such a shame Boris died before Last Temptation got made, but a lot of what he did survives in the film.

By now it’s 1983. And the budget is starring to climb from $12 million to 13 to? 16, and the shooting schedule is getting longer, and we’re going to shoot in Israel, where we’re a day-and-a-halfs flight from Hollywood if anything goes wrong, and they’re not exactly crazy about the casting—Aidan Quinn they could accept as Jesus, but some of the others made them nervous. And then the religious protests started, and a theater chain said it wouldn’t show the movie. Well, if you have a picture that’s pretty expensive by now, and you’re not sure it’s going to be profitable, and you can’t show it in a lot of theaters, and you’re getting flak from organized groups. . . .

So they dropped it. Then Jack Lang, the French Minister of Culture, tried to help finance it with government money. And there was a big storm over that, over there. Meanwhile, my agent, Harry Ufland, kept shopping it around to other studios. He kept the idea alive, he kept my hope alive, for three years. That’s why he’s listed on the credits as executive producer. He was great. But he was involved with other projects. Then I got Mike Ovitz in January of 1987, and within three months we had a deal at Universal.

Kind of ironic, since Universal has this rep as the black suits and black hearts of the movie business.

I never thought I could make a movie like this for a place like Universal. They represented a certain kind of filmmaking. But from the moment I met Tom Pollock and Sid Sheinberg, I felt a new attitude, a new openness. I’ve never felt such support from any studio. They never said change one thing. They made suggestions; everybody made suggestions. And they knew it was a hard sell. But from the very first screening of the three-hour cut, they were moved, they were teary-eyed, they just loved it. I just hope they get through everything. But the toughness you used to hear about Universal against filmmakers, that’s how tough they’re being in defense of this movie. The more they get slapped, the more they hit back.

Maybe they fought harder because of the charge that the film would fan the flames of anti-semitism.

Of all the things that come out: anti-semitic! I was totally shocked by this tum. I couldn’t believe it. I mean, if they have problems with a businessman trying to make money, then he’s a “businessman”! He’s not “Jewish.” It’s disgusting. Obviously it just shows them for what they are. And even Rev. Hymers later apologized for his tactics.

But the whole point of the movie is that nobody is to blame, not even the Romans. It’s all part of the plan. Otherwise, it’s insane. I mean, the Jewish people give us God, and we persecute them for 2000 years for it!

At least the controversy helped bring your film to a wider audience.

I do hope the controversy doesn’t keep this movie from being shown on cable. When even Bravo, the very best cable channel, buckles under to 30 or 40 protest letters and withdraws Godard’s Hail Mary from its schedule, you have to be concerned about the life of your movie. You have to be concerned about a lot of things when that happens.

The Last Temptation Of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988)

Between 1983, when Paramount passed on the project, and ’87, when Universal said go, you made two other films that might be called commissioned projects.

After The Last Temptation was cancelled in ’83, I had to get myself back in shape. Work out. And this was working out. First After Hours, on a small scale. The idea was that I should be able, if Last Temptation ever came along again, to make it like After Hours, because that’s all the money I’m gonna get for it.

Then the question was: Are you going to survive as a Hollywood filmmaker? Because even though I live in New York, I’m a “Hollywood director.” Then again, even when I try to make a Hollywood film, there’s something in me that says, “Go the other way.” With The Color of Money, working with two big stars, we tried to make a Hollywood movie. Or rather, I tried to make one of my pictures, but with a Hollywood star: Paul Newman. That was mainly making a film about an American icon. That’s what I zeroed in on. I’m mean, Paul’s face! You know, I’m always trying to get the camera to move fast enough into an actor’s face—a combination of zoom and fast track—without killing him! Well, in The Color of Money there’s the first time Paul sees Tom Cruise and says, ’’That kid’s got a dynamite break,” and turns around and the camera comes flying into his face. Anyway, that night, we looked at the rushes and saw four takes of this and said, “That man’s gonna go places! He’s got a face!”

But it was always Work in Progress, to try to get to make Last Temptation. And now that Last Temptation is finally done, I’ll be doing another movie about the difficulty of defining love. It’s one of three New York Stories; Francis Coppola and Woody Allen are doing the other two. Richard Price has written the script for me, based on something I’ve been thinking about for maybe 15 years. It tells the end of an affair between a famous painter, about 50, and his young assistant, whom he uses as a subject for his work. It’s based on the diaries of Anna Polina, one of Dostoevsky’s students. It begins at the end of the affair and goes to the very end of the affair. The dialogue is very snappy, because Richard has that touch, but basically it’s about a guy’s relationship to his work and the people around him. Is he able to love? Is he a loving person? Is this his idea of love? And if so, is it valid?

And then I’ll do a gangster picture, Wise Guy. I’ll be going back to my roots—it’s a real assault on these two guys living it up. And I’ll be working on style again. The breaking up of style, the breaking up of structure—of that traditional structure of movies. I like to look at that kind of movie; I don’t like to do them. I get bored.

In a way, it must be hard not to get bored, now that you’ve achieved this film that has obsessed you for so long.

I’d like to take a year off from my more personal projects and do a Hollywood genre film, with a good script, some wonderful actors. You learn craft. Every time you go on the set, even though you plan everything before, you realize how little you know. Or maybe I’ve just forgotten! The guys on the set ask, “What do we do now? Should we pan him over?” “I don’t know, I’ll probably lose it in the cutting anyway.” So what I’m doing now is thinking fast—I’ve always talked fast, but now I’m thinking fast. Always editing in my head: compression, compression, compression. Of course, I’ve just made a movie that’s two hours and 40 minutes!

I get stuck in between the European films of the ’40s, ’50s, and early ’60s and the American films. And I don’t know. I don’t know if I belong anywhere. I just try what appeals to me. And to get the money from America—which is very hard to do and stay within the system. I’m so glad Last Temptation was financed in Hollywood, that it’s an American movie, that an American studio was willing to take the flak. And I would like to do a movie with widescreen and a couple thousand extras, if I could keep my interest going. My everyday interest. Because I don’t enjoy shooting movies. There’s too many people around, too many things to go wrong, too many personalities, and you have to be very… rational. I don’t like being rational. I don’t like being held back.

The Last Temptation Of Christ (Martin Scorsese, 1988)

Answer a few points of contention, if you will. Some people, seeing the early scene in Mary Magdalene’s brothel, think that Jesus is watching Magdalene perform in a sex show.

Jesus and the other men are not voyeurs. They’re waiting, they’re not really watching. Some of them are playing games; two black guys are talking; Jesus is waiting. Magdala was a major crossroads for caravans, merchants would meet there. And when you were in Magdala, the thing do to was to go see Mary. But the point of the scene was to show the proximity of sexuality to Jesus, the occasion of sin. Jesus must have seen a naked woman—must have. So why couldn’t we show that? And I wanted to show the barbarism of the time, the degradation to Mary. It’s better that the door is open. Better there is no door. The scene isn’t done for titillation; it’s to show the pain on her face, the compassion Jesus has for her as he fights his sexual desire for her. He’s always wanted her.

At the last supper, Jesus says, “Take this and drink this, because this is my blood.” And when the cup is passed to Peter, he tastes blood.

That’s the miracle of transubstantiation. And in a movie you have to see it. Blood is very important in the church. Blood is the life force, the essence, the sacrifice. And in a movie you have to see it. In practically every culture, human sacrifice is very important, very widespread. When I was in Jerusalem, Teddy Kollek, the mayor, showed me the Valley of Gehenna, where the Philistines sacrificed their children.

The last temptation is one of a long, normal, and still basically sinless life. Except that Jesus commits adultery with Mary’s sister Martha.

I don’t know that it’s adultery. It might have been polygamy. There is some evidence of a Hebrew law at the time regarding polygamy for the sake of propagation of the race. But remember again, this is the Devil doing fancy footwork. “You can have whatever you want. And look, I’m sorry about what happened to Mary Magdalene. Really sorry, won’t happen again. In fact, this time, take two! You need more than one—take two!”

In the Gospels, does Jesus know from the beginning that he’s God?

Maybe, maybe not. There are hints both ways. In Matthew, the first time you see Jesus, he’s being baptised by John~ and God’s voice comes out and says, “This is my beloved son in whom I am well pleased.” But I think that was more to emphasize Jesus over John the Baptist. Because John was the one getting all the attention. I mean, this man had a presentation! He knew how to draw the crowds. But except in Luke’s gospel, where the twelve-year-old Jesus is presented to the elders, the question of when Jesus knew he was divine is cloaked in mystery. So we’re not saying this is the truth, we’re just saying it’s fascinating, it’s so dramatic, to have the guy make a choice. As if he could make a choice—I mean, if he’s two natures in one, he has no choice. But the beauty is that it gives the impression of choice. And eventually he has to say, “Take me back, Father.” It’s wonderful.

The final words of the movie—Jesus’s final words—have baffled translators for centuries. How did you decide which words to use?

Very hard to translate and get the power and the meaning. “It is finished.” “It is completed.” “It’s over.” Can’t use that—too Roy Orbison. What was the translation we were taught in Catholic school? “It is consummated.” The Kazantzakis book used “It is accomplished.” Because Jesus had accomplished a task, accomplished a goal. I shot three different versions. What I wanted was a sense ofJesus at the end of the temptation begging his Father, “Please, if it isn’t too late, if the train hasn’t left, please, can I get back on, I wanna get on!” And now he’s made it back on the cross and he’s son of jumping up and down saying, “We did it! We did it! I thought for one second I wasn’tgonna make it—but Ididit Ididit Ididit!”

So how do you feel after a decade of trying to get this temptation on film?

I thought for one second I wasn’t gonna make it. But Ididit Ididit Ididit!