By Patrick McGilligan in the July-August 1988 Issue

Interview: Dean Stockwell

An in-depth conversation with the protean actor, retracing his career from MGM kid to unlikely, oddball comeback

In his book Negative Space, critic Manny Farber writes about Hollywood sideliners, screen players whose fringe characterizations can stand out, like raisins in rice, whether in good, bad, or in-between movies. “Standing at a tangent to the story and appraising the tide in which their fellow actors are floating or drowning,” Farber says, “they serve as stabilizers—and as a critique of the movie.”

One of our best professional sideliners, nowadays, happens to be Dean Stockwell.

Born of show business troupers (his father, the publicity notes invariably mention, was the voice of Prince Charming in Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), Stockwell has had a long, intermittent, richly varied and at times climactic career. The first stage of that career was as a popular, ambiguous, glittering-eyed juvenile performer at MGM in the late Forties and early Fifties. By the time Stockwell was 15, he had acted in some 22 movies, including such pick-of-the-lot properties as Anchors Aweigh, Gentleman’s Agreement, Kim and (on loan-out to RKO) Joseph Losey’s allegorical The Boy with Green Hair.

Stockwell makes no bones about detesting the MGM experience, then as now. After finishing high school at the studio, the teenaged Stockwell quit acting, enrolled at Berkeley, dropped out, then, after shearing his trademark tousled hair, roamed the United States for roughly five years.

Hardscrabbling persuaded him that acting was maybe not the worst way to make a living. Back in harness, as a young leading man Stockwell acted in programmers, until he was cast as one of the two killers in Compulsion on Broadway, which led to his repeating the role in the film version, and other stellar performances during a flurry of motion picture activity in the late Fifties and early Sixties. For Compulsion and for his emoting in the screen adaptation of Long Day’s Journey Into Night, Stockwell received (“shared cast”) Best Actor honors at the Cannes Film Festival.

But Stockwell was still unhappy with acting, with society, and with himself. He was married, for two years, to actress Millie Perkins. He abandoned acting again, embraced the Sixties, and recreated, sex- and drug-wise, legendarily. When he was not keeping company with Beat Generation artists and intellectuals, he was hanging out in Topanga Canyon with Jack Nicholson, Neil Young, Eric Clapton, and longtime pal Dennis Hopper, with whom he has often worked.

By the time Stockwell had opted for a second comeback, the parts, for a middle-aged renegade child actor with an out-there reputation, had dried up. In the Seventies, Stockwell’s moodily offbeat presence could be glimpsed more reliably in dinner theater and episodic television than in the obscure films he made that were barely released. This nowhere period was capped by such projects as co-writing and co-directing Neil Young’s anti-nuke rock-and-roll comedy Human Highway, and by Stockwell’s bit as an Anglo military advisor in the Oscar-nominated Nicaraguan feature, Alsina and the Condor.

Again, Stockwell was discouraged. After meeting his wife, Joy Marchenko, at Cannes, a place with a lucky association for him, he decided to quit films yet a third time, to move to Santa Fe and to take up the sure thing of real estate. In 1983, the following advertisement was placed in the trades: “Dean Stockwell will help you with all your real estate needs in the new center of creative energy.” A telephone number in Santa Fe, New Mexico was listed.

Fortunately for moviegoers, fate intervened, in the persons of David Lynch, who cast Stockwell as the fiendish Dr. Yueh in the science fiction extravaganza Dune, and German director Wim Wenders, for whom Stockwell played the common-sensical brother of drifter Harry Dean Stanton in Paris, Texas, which won the grand prize at Cannes in 1984. Needless to add, the actor never did sell any real estate.

Since Paris, Texas it is clear that Stockwell is in the midst of an improbable and fecund third comeback in his career. The roles have included the pansexual weirdo who lip-syncs Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” in the den of iniquity in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and the hardbitten career soldier of Francis Coppola’s Gardens of Stone; memorable quick-fixes in To Live and Die in L.A. and Beverly Hills Cop II; and upcoming (this summer) pivotal roles in Jonathan Demme’s Married to the Mob and Francis Coppola’s Tucker, in which Stockwell plays none other than Howard Hughes. (“Surprisingly, I look a lot like him!”)

Manny Farber also writes about “centered” acting, which entails “deep projection of character,” as opposed to an “uncontrolled, spilling over quality.”

It is this “centeredness,” this uncompromising revelation of a faceted self, which has made Dean complicit with audiences, and a boon to filmmakers, for 40 years. In silly business like 1968’s Psych-Out, with Jack Nicholson fronting an acid rock band in the heyday of Haight-Ashbury, Dean’s eerily tranquil characterization (and the sacrificial death of his character) provides the only authenticity in what was, even at the time, a garbled timepiece. In Blue Velvet, his thoroughly oddball performance as Ben provides a sideliner’s window onto the edged surrealism of the rest of the movie.

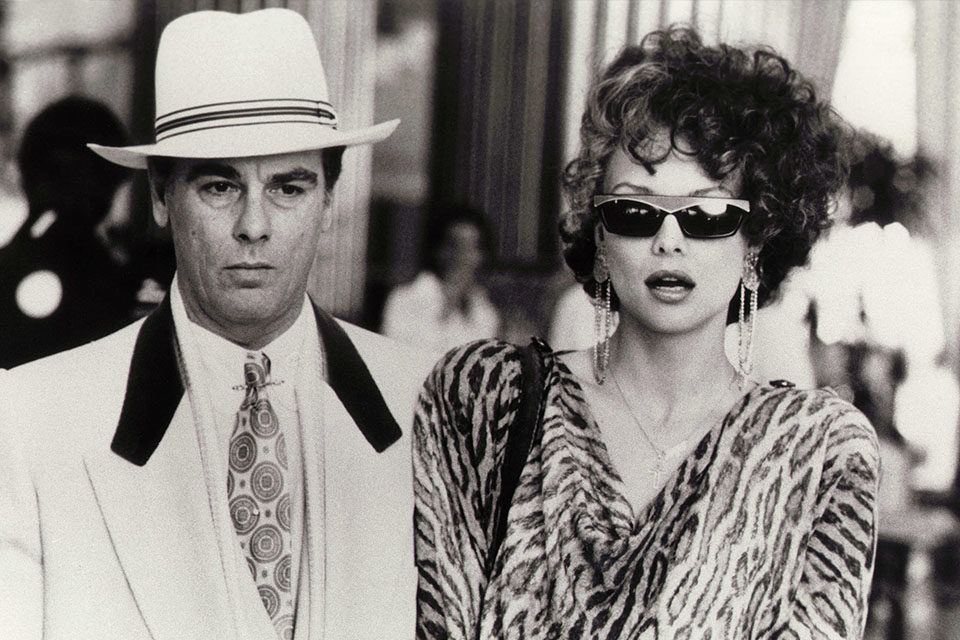

Stockwell’s resurgent joy in acting is found in the range, the looseness and the vitality of the parts in the Eighties. In director Demme’s new picture, Stockwell takes a rare leap at comedy as the cold-blooded, loose-zippered Mafioso Tony “The Tiger” Russo. It is a sly, full-bodied, captivating performance, the kind the Motion Picture Academy remembers come statuette-time. It may be misinterpreted as a way-out departure, whereas, like everything else he has ever done, it is very Dean.

When we met at a chic restaurant in Santa Monica, Stockwell was still recovering from an all-nighter of filming Dennis Hopper’s latest (with rockers Neil Young and Bob Dylan in the cast). He, was wearing blue jeans, cowboy boots, turquoise jewelry. He chainsmoked during lunch. An unlit cigar dangled in his shirtpocket for afterwards.

Did it help you as an actor that your parents were professionals in the business, and presumably role models? Does your acting approach come out of the home at all? Or does it come out of being honed at MGM?

Well, my father [Broadway actor Harry Stockwell] wasn’t there. My parents had split up by the time I was six, so he was not a role model at all. My mother [Betty Veronica Stockwell] had given up her career, which was as a dancer-singer-comedienne in vaudeville and “George White’s Scandals”—that type of thing. So her career really had very little bearing on the type of thing I was doing. I was the first film actor in my family per se. My home and my environment was MGM.

I don’t think working at MGM influenced me, as far as my acting goes, at all. I think that my acting was strictly intuitive, from the beginning, and has always remained that way. I resisted any attempts by anyone to assist me. Even when I first started acting, when I was six or seven, I always knew, when I was doing a scene, if it was right. I don’t know how I knew, but I knew.

How did you think about acting, as a boy, when you thought about it at all?

When it’s intuitive, that’s a bypassing, really, of the thought process. It’s a source that’s just prior to or more original than the thought process. When I did think about it, I thought about it in terms of honesty or truth or self, or how I would react, how I would feel, what I would do, and what I would say.

Did MGM have acting coaches and classes in which you were constantly worked over?

They had an in-house acting coach for years, named Lillian Burns… I used to have to go into her office and I hated it. I felt it was just such a waste of time. I had to sit there while she took the script and read the role and cried and laughed and did all this shit, while I just sat and nodded and wanted to get the hell out of there. That was my only coaching.

You talk about MGM in such measured terms. What was the upside of being there, for so many years, when you were growing up?

Well, the only upside that I can really tell you about pertains to where I am now, many, many years later. I have a profession that I’m more comfortable with, that I’m proficient at, and which I need to support my family—my two children and my beautiful wife. I have no idea what I would have done—I might have been a lawyer, I might have been an artist, I might have been a physicist. Who knows? But at the time, when I was a child, I didn’t see any benefits, and in retrospect, I don’t see any benefits now.

You were unhappy at the time?

A great deal of my childhood was not there for me, because I was working. I was doing two, three pictures a year, and in between I was going to school on the lot. It was the full-bloom fruition of the motion picture industry. It represented the pot of gold for most people who were striving to achieve this big payoff of fame, glamour, and money. There was a lot of pressure to succeed. A lot of demands were placed on me that should not be placed on a child, at all, ever.

When you look back on those pictures at MGM, do they give you any gratification at all, after all these years? Or do you experience a different kind of twinge?

Some of them do give me gratification, in retrospect. But the ones I appreciate now, or have some affection for now, I also appreciated to some degree at that time. Occasionally a picture like The Boy with Green Hair came along. The war was all around us, constantly, so I took that film very seriously, very purposefully. I felt a certain sense of pride in that film and I still feel good about it. A lot of people involved in that film were blacklisted, including the director, Joseph Losey. It was my first radical film project [laughs].

You stopped acting altogether after high school and dropped out of show business for roughly five years. Why?

Well, I desperately needed to get out of the whole thing. I didn’t really formulate it in my head that I had to find myself or see the world, I only had to get away from MGM.

I used a different name—my real first name, which is Robert—and I cut all my hair off. I had to earn whatever money I lived on. I was doing a lot of odd jobs in California and New York. By the time I was 20 or 21 it became clear that I had no tools to go into any profession. My education was poor at best because it was geared towards accommodating the work. There were only three hours of school a day, which was constantly interrupted by having to go in and do the shots. I had to re-teach myself to read later on.

So I thought I would try acting again, and contacted my agency, MCA. I got a little part on a religious show in New York that paid me $150, which got me back to L.A. I did a number of live television dramas, a couple of stupid movies, and then in part through a friend, or a lover as it were, a wonderful actress named Janice Rule, I was cast in Compulsion for Broadway.

Compulsion legitimized you all over again in the film industry, and you appeared in Long Day’s Journey Into Night and Sons and Lovers. But during the early Sixties, you accepted few parts and only those, it seems, which made demands of you.

Yeah. I was turning a lot of things down. I was making my own career decisions, as I am now, and I wasn’t finding things that appealed to me. I wasn’t going in a specific direction. I just analyzed and reacted to whatever material came along. Ironically, I couldn’t give myself any credit. I would denigrate my own accomplishments.

I read that you destroyed your best acting prizes from the Cannes Film Festival for Compulsion and Long Day’s Journey.

Yeah, one drunken night I threw them into the fireplace. They were scrolls. At the moment it happened—I vaguely recall it—I remember thinking that the scrolls that Cannes provided for the prix de masculin were ugly, stupid-looking things. But in a deeper sense they reflected my resentment: Poor Dean!

You went to some acting classes during this period.

I went to some classes around town, and I went once with some people to the Actor’s Studio in New York. Lee Strasberg was conducting something, and I walked out after about 15 minutes. I thought it was horrendous. I was going to classes, to be perfectly frank, looking to get laid.

You were not at all insecure about your acting?

No. And I didn’t like the classes. I did not like that highly critical atmosphere which is damaging to an actor’s sensibility.

How did the Sixties affect you?

In a very positive way, I think. It certainly looked, for a long time, as though the Sixties affected my career in a devastating way. For anyone who was there, who remembers it, it was a profound time that stretched clear around the world: of enlightenment, of awareness, of a critical view of society. The flower children and the love-ins, the Beatles, were the childhood I didn’t have.

So I quit working. I told my agent I wasn’t going to work for three years and I didn’t. I just participated in that and I loved it.

The sexual aspects of the Sixties I found incredibly positive. When I arrived at puberty, sexual mores were very rigid and unreasonable. It was frustrating. When it opened up, I found it to be very beneficial.

Can you extrapolate what it is about having gone through the Sixties that has changed or deepened your approach to acting?

Nothing has deepened my approach. The approach was always deep because it was always intuitive, and intuition is a very deep part of the self. Very mysterious. The approach remains constant throughout. But the instrument of the self becomes more rich and varied as it experiences life. The Sixties were the richest and most varied experiences that I had, so I unhesitatingly say that they had a very positive effect on my work now.

When you returned to acting, in the late Sixties and early Seventies, it must have seemed like a time warp, with all the old studio moguls dead or dying, and the studio systems changed and in disarray.

I was very happy that all of it was disappearing. Independent filmmaking allowed more freedom of expression, more diverse talents to emerge. The films made today are as good or better than those made in the classic days of Hollywood. There are a lot of lousy movies being made now, but also a helluva lot more experimentation.

But you also had trouble landing parts.

All through the Seventies I couldn’t get arrested half the time. I was averaging $10,000 a year in income.

Were you going in for a lot of readings?

Yeah. But I never got a job I read for in my life. Never. So I don’t read anymore. Sometimes I’d ask a producer or director I knew if they’d check around and find out if there’s a bad rap on me, or if I was on a modern-day version of a blacklist, or what.

Did you have a reputation for being difficult on the set?

No. Never. I’m a total professional. The only filmmaker I ever had a problem with was Henry Jaglom.

Dean Stockwell and Michelle Pfeiffer in Married to the Mob (Jonathan Demme, 1988).

Nowadays you gravitate toward the offbeat, fringe material.

Strangely, the gravitation works not from me to that material, but from that material to me. The only project I sought myself was Dune.

Why is that?

I knew you were going to ask that!

Let’s talk about some of those cutting-edge directors. What about Dennis Hopper, with whom you’ve now worked twice, and with whom you are now filming another picture. He has been your close friend since the Fifties. Is it a case of him starting a sentence, and you finishing it?

Sometimes it can be like that, yeah.

How would you characterize Dennis as a director?

Number one, it’s a job. The fact that it’s Dennis’ project makes it a wonderful job. Because Dennis is at the top of the talent side today, as a focused filmmaker and as an actor. He doesn’t work with any formula. He is knowledgeable about film history. He is very respectful of all the great filmmakers who have preceded him. He has learned from all of them. But he creates a fresh film each time. It always has Dennis’ stamp on it.

What does he do to help you as an actor?

He leaves me alone. If a director leaves me alone, I do my best work.

David Lynch?

David and Dennis share a certain facet of their vision—although I’m not sure either one would agree with me. Both of them have at least a streak of surrealism in their souls, and I have always been very partial to surrealist art, to surrealist thought, to surrealist being. I think Blue Velvet is surrealistic, and Dennis’ film is definitely surrealistic-and a great movie, incidentally. In Colors there is very little surrealism, but it’s there, if you know Dennis.

How do you prepare for your roles?

When I first read the material, nine times out of ten what I am going to do with it falls into place at the first reading. Or at least 80 percent of it does. The remaining 20 percent falls into place by itself over a period of time prior to when I start shooting.

How do you feel about rehearsals?

I hate rehearsals. I have always hated rehearsals. You have to do it out of respect to the director, the other actors and the material, sometimes. When it comes to, say, a piece like Long Day’s Journey Into Night, which was taking a play verbatim and translating it onto the screen, you have to rehearse a lot. I have found ways to rehearse positively now. But I would still rather not do it.

It goes stale for you in rehearsals?

No. It’s just a waste of time for me. I don’t like to do what I do unless the camera is rolling. Any good film actor has to be able to do ten takes of something and to get very close to hitting what he is after each time, but it is always going to be a little bit different. I hate the idea of doing something, knowing it is right on, and that it is rehearsal.

Do you think of yourself, these days, as having a certain persona, in terms of what you give off on screen, the connections you are making with the audience?

I think about that quite a bit. Because I think there’s a certain point in the life of an artist when his work begins to communicate most fully. I seem to be approaching the height of my communicative powers now. I find I am able to do less and communicate more with greater ease than ever before. I feel almost a sense of power about acting, now.

The new role, in Jonathan Demme’ s Married to the Mob, is a very playful one for you—you are teasing the audience as well as the character—and the performance is less intense than what we have seen in Blue Velvet or Gardens of Stone.

No character has ever come to me as clearly, as easily, and as fully as Tony “The Tiger.” It was almost as though I had done it before in another life. I don’t know whether it is because I’m half-Italian, or that I’ve never had the opportunity to do this type of role before-a woman-chasing, amoral, top dog Don. But I just lit up the minute I read it and I didn’t have to touch it. There! Solid. Completely.

But I get the idea that, in Married to the Mob at least, acting isn’t work any longer, it’s fun for you.

It should be fun. It wasn’t for years and years and years. Now, in this third stage of my career, all that has completely turned around and good luck is still with me. Now, I am finally able to enjoy it.