By Jonathan Romney in the November-December 2017 Issue

Inner Voice

French-Senegalese filmmaker Alain Gomis expands upon his ambiguous cinema of experience and identity with Félicité, the story of a Kinshasa singer in crisis

The title of Alain Gomis’s feature Félicité is also the name of its heroine—or rather, it isn’t quite. Late in the film, we discover that the Congolese singer played by Véro Tshanda Beya Mputu nearly died as a child; when she recovered, her grateful family replaced her African birth name with a French word for joy. Mputu’s usually solemn, sometimes unreadably absent expression seems to express anything but joy; perhaps one reason is that Félicité’s name leaves the character stranded between cultures, between her African identity and a borrowed word from a European colonial power.

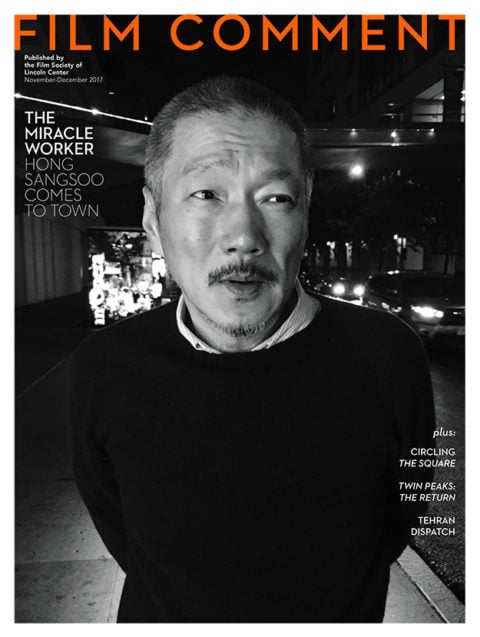

From the November-December 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

Félicité may be Alain Gomis’s least overtly political film, but this French-Senegalese director has consistently explored themes of hybrid identity in the post-colonial world. The title of his first feature, L’Afrance (2001), says it all: the film addresses the experience of inhabiting a place, or a state of being, that is neither la France nor l’Afrique, yet is somehow (soul-destroyingly? or invigoratingly?) both at once.

The same African-European cultural dialectic plays out in Félicité both in text (with dialogue in French and Lingala, the film also contains a quotation from Novalis’s poem Hymns to the Night) and in music, with on-screen performances from Kinshasa band Kasai Allstars and the Kinshasa Symphony Orchestra playing the haunting compositions of Estonian “holy minimalist” Arvo Pärt.

Félicité is ostensibly a realist narrative about an independent single mother struggling to get by in tough times. Félicité is self-possessed but also wary of the world and of time-wasting men such as Tabu (the charismatic Papi Mpaka), a bullish lothario and drunk who is cock of the walk at the local club, but a shy, gauche presence when he comes to fix Félicité’s fridge. Crisis comes when Félicité’s teenage son is injured in a traffic accident. She heads out in search of the money she needs for his care, vigorously chasing debts and, in one hair-raising scene, talking her way into the house of a local potentate. She gets bodily dragged out, stands up to face the man, is knocked down again, and leaves the house battered—but with money in her pocket.

Félicité

All this takes place against a quasi-documentary backdrop, as the camera (the DP is French stalwart Céline Bozon) cruises Kinshasa’s streets, squares, and suburbs, sometimes piling into abrupt action, such as a bloody tussle in a crowd. At other moments, the film is harder to classify, with Gomis disrupting his ostensibly realist textures. Music sequences interrupt the action, as Félicité and Kasai Allstars take the stage to play their turbo-powered dance music, driven by guitar and vibrantly distorted thumb piano. More perplexingly, there is no narrative motivation in Gomis showing us the orchestra, and later a choir and soprano soloist, as they perform Pärt. In addition, the Pärt pieces (among them, “Fratres” and an extract from the choral “Seven Magnificat Antiphons”) accompany segments of an eerie night sequence running through the film: in barely penetrable darkness, Félicité explores a forest, wades across a river, and eventually encounters a solitary okapi (something like a miniature zebra-striped giraffe), which then magically appears in an empty dance club. Whether these episodes signify a dream, a mystical oasis away from Félicité’s daytime turbulence, or an Orpheus-like venture into the spirit world in search of her comatose son’s soul, they make Félicité more richly alluring than a straightforward urban chronicle.

Born and raised in France, Gomis identifies himself in his official bio as “Franco-Bissau Guinean-Senegalese.” He studied art history and film at the Sorbonne, and has listed Eisenstein, Murnau, Tarkovsky, and Vigo among his influences, with the Senegalese innovator Djibril Diop Mambéty as his hero among African directors; he also received early encouragement from Burkinabé maestro Idrissa Ouedraogo.

Gomis’s earlier films were more elusive in their fragmented style and their mixing of narrative, artistic allusion, and political debate. They feature characters who were not French-born like him, but African visitors who find Europe too much a magnet, or a prison, to easily leave. In his short Whirlwinds (1999), hero Ousmane wants to return to Senegal, and chides his friends for criticizing the mother country: their excuse, he says, for staying in France. There are other reasons for staying: an African dandy grins to camera, showing off his Kenzo shoes and Issey Miyake shirt. “I’m not at home here,” Ousmane complains, but Gomis cuts to footage of a Paris demonstration by African immigrants: “Our home is here,” reads a placard. Whirlwinds mixes such juxtapositions with scenes of overt political debate. In the end, Ousmane rips up his ticket home—but does that mark defeat, or victory over his indecision?

L’Afrance

Confidently expanding on Whirlwinds, L’Afrance is itself a whirlwind of narrative and discursive fragments. Like the short, it quotes the 1961 Senegalese novel Ambiguous Adventure by Cheikh Hamidou Kane, whose protagonist Samba Diallo visits Paris only to find himself caught between two cultures, and finally kills himself because he is “lost… hybrid.” L’Afrance’s El Hadj (Djolof Mbengue) is in a similar position: he’s working on a politics thesis, living with other exiles in student housing, and dating a white woman (Delphine Zingg). He believes it’s essential to return and support one’s country, but he’s held back by the new life he has discovered in France. Manhandled by cops when his residence permit expires, El Hadj nevertheless does all he can to stick around, working on a building site, then getting involved in the traffic of false passports. He’s proud of his specific identity—“I’m tired of being un black,” he complains, “I’m Senegalese.” But he knows how fragile identity is. A co-worker recalls that on his return to Senegal, people there treated him as an outsider; estranged from his origins, he saw Senegal “as if in a film.”

That sounds like the worst kind of alienation; yet from a filmmaker’s point of view, seeing the world like a movie might offer a kind of redemption, or a way of apprehending life in all its contradiction. Consequently L’Afrance barrels restlessly from narrative fragment to fragment, its rough-edged realist shooting style sometimes giving way to a more expressionist language, like the long, still opening shot of El Hadj’s blank, dreamy face as liquid, apparently blood, drips onto him from above.

Less cogent but hugely inventive, Andalucia (2007) is effectively a replay of L’Afrance in a picaresque comic mode, this time with a North African hero, Yacine, played by lanky Samir Guesmi (a supporting player in L’Afrance and one of this century’s most visible faces in French cinema). Outsider intellectual, romantic hero, and anguished clown, Yacine is seen variously working as a playleader and a tour coach guide, doling out soup to the homeless and—in one farcical episode—donning a powdered wig as an extra in a heritage movie (“Fucking French cinema!”). His Algerian family lives in France, but his father has converted to Christianity, following a vision of St. Augustine (himself, of course, North African). Even more breakneck than L’Afrance, Andalucia follows Yacine through assorted adventures and romantic interludes, including one with a Chilean circus acrobat.

Andalucia

The seeming lack of coherence in Yacine’s life motivates the “whirlwind” approach to editing, the abrupt leaps into crisis: he’s suddenly seen, without explanation, smashing up a jewelry store. Finally, things arrive at a dreamlike order. A Spanish woman in the street tells Yacine to go to Toledo: sure enough, he now walks spellbound through various cities in Spain, as if searching for himself. And he finds himself—or his near likenesses, the emaciated, distinctly Maghrebin faces in El Greco’s portraits. Surrounded by Moorish architecture, he has landed in a similar hybrid space to that suggested by the title of L’Afrance—a Spain that is part Europe, part Islamic North Africa.

Gomis shifts into an entirely different mode in the parable-like Today (aka Tey, 2012)—for my money his finest achievement. Its premise is simple: the Everyman hero wakes up knowing that this will be his last day on earth. Satché, played by U.S. poet and rapper Saul Williams, wakes in his parents’ home in a middle-class neighborhood of Dakar. He finds friends and family gathered to pay tribute, showering him with praise—and then with merciless criticism. Still, this being a sort of birthday in negative, he’s treated like a king (“No one must waste his time today”) as he walks through Dakar on a last victory lap.

Satché truly comes alive now, soaking up the sights, sounds, and vibrations of Dakar—like Félicité, Today is a city symphony—as if for the very first time. But his day is also a leave-taking and a reckoning. He hangs out with his male buddies and best friend Sélé (L’Afrance lead and Today’s co-writer Djolof Mbengue); then he visits his former mistress Nella (Aïssa Maïga), an elegant modern art gallerist who first plays hide-and-seek with him, then coolly taunts him. Satché eventually arrives late for an official town hall ceremony in his honor, mercifully missing the speeches; in a beautiful, oddly comic shot, hundreds of discarded plastic cups from the reception rattle across an empty courtyard.

Today

Throughout, Gomis proceeds with minimal dialogue, in stark contrast to the debate-heavy L’Afrance. At times resembling a dance movie, Today—shot by Céline Sciamma collaborator Crystel Fournier—centers on Williams’s body, his easy, loping gait, and his candidly open features. At certain times, Williams’s Satché will grin radiantly, reveling in what’s around him; at others, his face seems heavy, laden with the weight of an entire life. It’s an audaciously counterintuitive move to cast a man associated with hyper-fluid verbal energy in a film so much about silence.

Toward the end comes an eruption of the real in its rawest aspect, bringing a documentary edge to this parable: a montage shows us a woman railing against shortages (“We’ve had enough—especially the women”), a host of other people protesting against the status quo, then one of those sudden bursts of violence that are a constant, either directly or in TV footage, in Gomis’s work. Here, it’s a demonstration followed by a police baton charge—the context being the political unrest that would lead to the unseating of Senegal’s president Abdoulaye Wade in April 2012 (shortly after Today’s Berlin premiere).

After this explosive interlude, Today ends with a gentle, seemingly anticlimactic, yet audaciously poetic coda. Satché comes home to a cool reception from his wife Rama (Anisia Uzeyman). He plays with their two young children, and a series of fragmentary images fill the screen: Satché’s eyes in extreme close-up, a spider on a tree, Rama in slow motion, water on a child’s face. Satché and Rama make love—today, or in his memory?—before, with evening drawing in, they sit in the yard talking (we don’t hear what they’re saying). Then Gomis executes a magical coup de cinéma: as night finally falls, the two children, now fully grown, walk past their parents and leave the house.

Félicité

In contrast to Today’s otherworldly drift, Félicité returns to Gomis’s earlier, harsher tones, but also offers something new—a female perspective. That’s not entirely unprecedented for him: the 2003 short Little Light is a charming vignette of childhood, of awakening philosophical awareness in a young girl (Assy Fall) as she measures the fleetingly glimpsed textures of her daily life in Senegal against her fantasies of a polar ice floe seen in a picture book. Félicité, though, stands as a corrective to the earlier viewpoint of the films’ male characters—as in Whirlwinds’s conversation about the comparative advantages of sleeping with white or black women. Men in Félicité are often appalling or ridiculous—the brutally dismissive grandee, the ex who is completely unconcerned with helping their son and can only berate her for her pride. Félicité has her autonomy and her artistry to keep her going—the intensity of Mputu’s onstage singing is mesmerizingly authoritative—but eventually, she also has love.

This proves to be a humorous, adversarial form of tough love with erratic blowhard Tabu, as she mocks his clownish arrogance (“I’m greater than all the stars,” he declares) and he courts her with improbably poetic compliments (“Your face… like an armored car”). It’s a love that will clearly be charged with conflict and yet, we sense, will be on her terms. At the end of the film, Tabu leaves the club with another woman, but Félicité walks into his bedroom and calmly boots her rival out. This might seem a dubious sort of happy ending, but for the ironically named Félicité—who until this moment has known the sufferings of a female Job—it’s as good as it gets.

Read our interview with Gomis.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.