Once upon a time, back in the mid-seventies, Thomson was that rarest of rarities, an intelligent enthusiast, at once better-read and hipper than his auteurist brethren. That early enthusiasm, so different from the highly readable disengagement of his later writing, feels like a burst of sunshine as you come upon the largely unchanged entries on Cary Grant or Howard Hawks or Max Ophüls. But the distanced skepticism that eventually crystallized out of the early rapture is pretty questionable. From a purely rational standpoint, it’s astonishing that someone so intelligent is still peddling outdated notions about the vulgarity of the medium or cinema’s inferiority to literature, and doubly astonishing is the fact that he’s getting away with it. He’s worked up a devilishly artful act, an endless shadowboxing match with the standard clichés of cinema-as-Dream-Factory, which is merely the minor-key flip side of AFI 100 Best lists or $50 coffee-table editions of George Hurrell photographs. Thomson’s writing is to official movie culture what American Beauty was to American life: a sly celebration in the guise of a piercing critique. He has written a plum role for himself as the charismatic skeptic, the Dr. Johnson of Movie. Which allows him to slip and slide all over the place. A little vamping here? An error in fact there? Who cares when movies are the stuff that dreams are made of, and we’re all dreaming together.

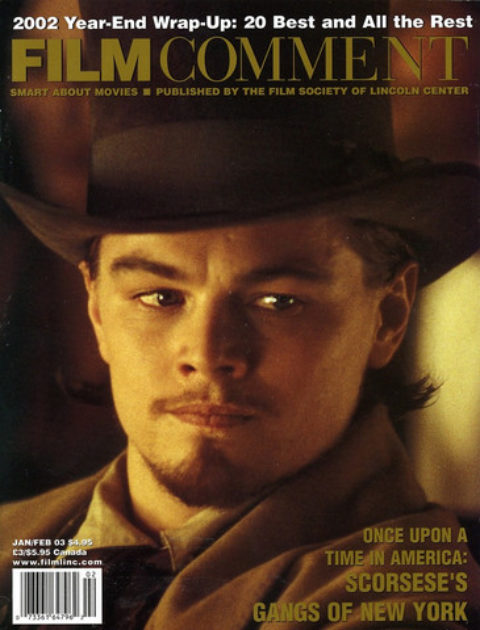

You can read the complete version of this article in the January/February print edition of Film Comment.