Sundance Dispatch #1

Manchester by the Sea

The Sundance Film Festival has always existed as a bit of an escape. An escape, for 10 days, from the more traditional, often conventional, movies that draw the majority of moviegoers to multiplexes. Along the road to its prominence as the premier festival for new American film, particularly in the Nineties, films from this casual festival—staged mostly in makeshift movie theaters in Park City, Utah—have punctured the traditional distribution system to find wider audiences.

Big corporate brands joined the fray over the past 15 years, and today the festival can be on the one hand easygoing yet, on the other, overcrowded and ostentatious. Recently, some of its films (such as Boyhood and Whiplash) have gone on to win Oscars, raising the stakes and the expectations for the annual event. So each January nearly a thousand journalists and many more thousand industry types crowd in to see (movies) and be seen (at parties).

For longtime fans of Sundance who keep coming back for more, though, the festival retains an essential element of surprise—and of discovery. It remains a place to find a fresh crop of films and filmmakers at the start of every year.

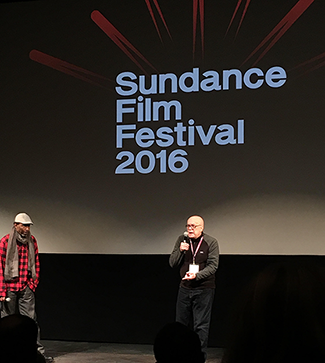

Festival founder Robert Redford, on the opening day of the event here, underscored the fest’s independent spirit and emphasis on diversity but also warned of ongoing challenges.

“Independent film is not in a good place,” Redford said during his annual press conference inside the intimate Egyptian Theatre on the town’s tiny Main Street. He noted the persistent challenges of raising money to make movies and then securing meaningful distribution in an increasingly digital, on-demand universe. “It survives because it has value,” he added, “but it’s always been tough.”

Film Hawk

Sundance’s other “Bob” was also in the spotlight on its opening weekend. Nearly 80 years old, indie film producer and consultant Bob Hawk has been a fixture at this festival, and within the indie community, for decades. Credited with discovering Kevin Smith, Ed Burns, and other Nineties indie filmmakers, the always enthusiastic figure has been a champion and mentor to many for the lifespan of modern American independent filmmaking.

On Sunday, he was celebrated with the screening of a new documentary about him, JJ Garvine and Tai Parquet’s Film Hawk. It is a sincere, rough-around-the-edges portrait of an instrumental figure who still struggles to make ends meet as he devotes time and expertise to nurture creativity among those he cares about. The scrappy doc depicts the early days of a gay kid from New Jersey escaping to San Francisco where he influences early queer cinema before hitting the depths of depression and nearly taking his own life in the Nineties. Since then, Hawk has sacrificed fame and fortune to pursue projects that matter to him. His efforts have paid off big time for many of his friends and clients.

“For me, Bob is a mentor,” Sundance Festival head John Cooper declared, his voice cracking and tears appearing on his face as he introduced the early-morning premiere screening. “He taught me that film has many faces. Sundance would not be the same without Bob’s influence.”

“This man is my hero, my fucking legend,” Kevin Smith chimed in, holding the microphone alongside the emotional Cooper. The two men were the first of many who said they wouldn’t be where they are without him.

After a standing ovation welcomed Hawk to the stage following the screening, he shared a few insights and warned filmmakers in the audience to check their reasons for getting into independent film.

Money shouldn’t drive the indie community, Hawk warned. “That cannot be the motivation. You have to measure the success of what you create by its impact on other people.”

A former programming advisor to the festival, Hawk has helped countless indie filmmakers gain attention here over the decades. Today, Sundance organizers sift through some 12,000 submissions before locking a lineup of about 120 features and some 75 shorts.

On this edition’s opening weekend, Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea was an immediate hit among critics and insiders. In a year that featured new work by veterans such as Whit Stillman (Love & Friendship) and Todd Solondz (Wiener-Dog), Manchester by the Sea is a film that most seemed swiftly to agree would achieve wider acclaim throughout the coming year.

Love & Friendship

At this festival, if attendees don’t quickly concur that one or two films will travel, cynicism can take root. And so it was, in the opening days, that some folks complained that a few Sundance 2016 films were just too weird.

“Some attendees, especially distributors seeking potential hits, are complaining that this year’s festival has fallen too deep into the art house rabbit hole,” The New York Times reported this weekend. Well, the same complaint emerged a couple of years ago, but a few years before that, observers were grousing that the festival had become too mainstream.

An unlikely superstar on the opening weekend was the late Christine Chubbuck, the Sarasota TV journalist who killed herself on the air more than 40 years ago. Perhaps because she did so at a rural station and the videotape of the broadcast went missing, her story has almost entered the realm of myth, and the legend also persisted, inaccurately, that it inspired Paddy Chayefsky’s screenplay for Sidney Lumet’s Network.* The lead character in that film was an angry TV network newsman; Chubbuck was soon largely forgotten.

At Sundance this year, her story is powerfully portrayed by not one but two actresses: Rebecca Hall in Christine, the third feature film by Antonio Campos (Afterschool, Simon Killer); and Kate Lyn Sheil in Kate Plays Christine, a new documentary by Robert Greene (Actress, Fake It So Real, Kati with an I).

“In keeping with Channel 40’s policy of bringing you the latest in blood and guts, and in living color, you’re going to see another first: an attempted suicide,” Chubbuck said as she sat at the anchor desk on that July afternoon in 1974, before pulling a gun from her purse, placing it at the base of her skull, and pulling the trigger.

Christine

In the somber and superbly crafted Christine, Campos steadily reveals Chubbuck’s solitary life and mental challenges, building toward the dramatic moment. Greene’s insightful and ingeniously conceived Kate Plays Christine opens with a glimpse of the staged scene and then follows Kate Lyn Sheil as she travels to Florida to investigate Chubbuck’s life and meticulously prepare herself to portray the woman in her final moments.

“I knew that making a movie about Christine Chubbuck would be a difficult task for me,” Sheil told me in an interview this weekend. “[But] I do think that Christine Chubbuck is a fascinating character. To explore the life of a woman who is a bit of a mystery is perhaps unsolvable . . . but she was a complicated and driven woman who decided to end her own life. In fictional films I am drawn to characters like that, and observing her as a real person, I was drawn to her story.”

Sheil’s efforts to embody Chubbuck offer Greene an opportunity to establish a window onto the creative instinct. The cumulative effect of watching Kate Plays Christine, observing an actress’s “process” and being titillated by the sensational story at its core, is both disconcerting and mysterious. By the time it reaches its unnerving conclusion, the documentary has expertly opened up inquiries into gun control, mental stability, media criticism, and gender issues, as well as voyeurism and the very nature of performance.

Kate Plays Christine

“The movie is about Christine Chubbuck, but simultaneously it’s about the process of creating something out of nothing,” Sheil elaborated. “And that, I think, is why it’s so difficult to explain. The initial conjuring, of creating something out of nothing, is a very amorphous and personal thing that is hard to explain.”

Campos’s Christine addresses many of the same topics, perhaps from a slightly safer—yet no less profound—distance.

Rebecca Hall explained, during a post-screening Q&A over the weekend, that she studied depression and also watched video footage of Chubbuck. Ultimately, however, she explained that she had to let go of these links to the real woman so that she could imagine how the character might feel.

“It was a lot of absorbing and sitting on it, and slowly she arrived,” Hall said at the Q&A.

Asked whether she’d heard about the other Sundance film that features an actress trying to make sense of Christine Chubbuck, Hall said that she only learned about Sheil’s movie when the Sundance lineup was announced last month.

“I’d like to see it,” she added.

The Sundance Film Festival continues through Sunday, January 31. Eugene Hernandez will be filing additional dispatches from the festival later this week.

* Correction courtesy of Dave Itzkoff of The New York Times, the author of Mad as Hell: The Making of Network and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies. Itzkoff explains: “The chronology just doesn’t work. Chayefsky started writing Network as early as Dec. 1973, having decided that his anchorman character would have a crack-up on air and threaten to kill himself. Chubbock died in the summer of 1974. It’s an eerie coincidence but in no way inspired his writing.”