Rotterdam 2019 Dispatch

Present.Perfect. (Shengze Zhu, 2019)

Roughly coinciding with the industrial behemoths Sundance and Berlinale, the International Film Festival Rotterdam can sometimes seem lost in the shuffle, too aesthetically and culturally distant from the red carpets at the Berlinale Palast and the Canada Goose-clad hype-orgy at Park City and yet not quite far enough. Rotterdam has the unenviable task of competing for world and international premieres with Berlinale and Sundance, a state of affairs that finds their programmers jockeying for titles with the Berlinale’s Forum and Panorama sections (which have been exceptionally strong the past few years, likely due to an influx of films that would’ve otherwise opted for Rotterdam). Rotterdam has proven a formidable festival context for seeing new and recent experimental cinema, art exhibitions related to cinema, and the odd interesting restoration or revival, and it’s this combination of programming strains that comprises the festival’s key distinguishing trait, the reason for its enduring relevance within an increasingly crowded film festival marketplace.

But first, a word about the winner of this year’s Tiger Award (the festival’s main competition’s top prize), Shengze Zhu’s Present.Perfect. A stark formal departure from her previous film, the tableau-heavy family chronicle Another Year (2016), Present.Perfect. is a consummately contemporary take on the found footage documentary. Culled from over 800 hours of material, the film captures the world of Chinese live-streaming, the internet practice by which performers (“anchors”) use their webcams to record themselves just kind of doing whatever they feel like, and responding to questions and comments from the members of their unseen audience. Digital spectators can send the anchors cash-valued online gifts, in effect transforming this medium for self-expression and social connection into a potential source of income. But Zhu focuses largely on marginalized, disabled, or eccentric figures. The cast of anchors we spend time with include a chain-smoking burn victim, a hilariously bored single-mother seamstress, a sort of willfully inept street dancer, a man with hormone growth deficiency, and a handful of others. Zhu’s decision to use the live-stream footage rather than traditional interviews opens up a new space within which to consider Chinese society: she enables us to spend time with people who, in various ways, have been left behind by the nation’s swelling economy, earning money by performing as themselves through their testimony and reacting to questions put to them by strangers. A politics forms within the gaps between the various subjects that we encounter, yielding a portrait of China at-this-very-second that is as allusive as it is curiously engrossing.

Monument (Jagoda Szelc, 2018)

Just as surprising from an entirely different angle, Monument, the sophomore feature by Polish director Jagoda Szelc, is surely the year’s great anti-internship movie. Set at a hotel that is welcoming a new crop of young summer interns, the film inexorably tracks their escalating madness under crummy working conditions and the faint vibe that something witchy is afoot. Their manager cuts a figure like Joan Bennett in Suspiria with Robyn’s haircut, and her hardcore humorlessness and fascistic approach to supervising the interns—hovering over them as they perform their routines like an especially perverse drill sergeant—signal that this won’t end well for our proletarian coeds. Szelc renders the proceedings with maximum punchiness and, thankfully, refuses to ground the interns’ collective descent in the supernatural. A film thick with unsettling atmosphere and visual ideas, Monument makes one newly anxious to go on whatever bad trip Szelc concocts next.

Memento Stella (Takashi Makino, 2018)

The latest by Japanese experimental filmmaker Takashi Makino, Memento Stella, marked probably the festival’s most pleasant surprise: an arresting, hourlong abstract work, it screened in one of Rotterdam’s venue’s IMAX theaters, and the result was predictably mesmerizing. Accompanied by a score by the Dutch musician Reinier van Houdt, Memento Stella is comprised of some vast number of superimposed images, sometimes flirting with figuration (one can faintly detect rippling water, possibly the froth of the ocean, and a lateral movement past structures suggesting a drive down an urban street) but more often than not contenting itself to drown in the specks of visual data as they flit into view for a half an instant before vanishing just as quickly. The film’s title and Makino’s artist statement in the program suggest a concern with the celestial, but the effect was altogether more like being bombarded by some cryptic luminescence while straining to grasp an indeterminate yet cherished object just beyond reach. That is to say, it was quite beautiful, and the IMAX certainly didn’t hurt Makino’s bid to obtain a viewing experience pitched somewhere between the sea and the stars.

Dimanche (Fabrice Aragno, 1998)

The festival’s shorts programs and exhibitions were the more or less agreed-upon highlights of this year’s edition. The Swiss filmmaker and frequent Godard collaborator Fabrice Aragno was on hand to present a selection of his own short film. Aragno, the cinematographer of Film Socialisme, Goodbye to Language and, most recently, The Image Book (which he also produced), showed a 35mm print of his own graduation short, Dimanche (1998), a breezy, gorgeously shot vignette concerning a couple going their separate ways amid a long delay at a border crossing while on their way back from some weekend retreat. The program then raced ahead to the present, and his engagement with JLG: Locked in the Whirlwind (2014), an associative essay-film that bears out the influence of Godardian thought, tracking a hat motif across a selection of classic Hollywood films in the analytical style of Histoire(s) du cinema (1989-99); Promenade dans Le gai savoir (2017), in which Godard’s own Le gai savoir (1969) receives the same sort of treatment, with a particular emphasis on how language functions to elucidate and obscure within the context of an artwork that itself takes the status of language under capitalism as one of its primary subjects; and Suite lacustre, a new, almost diaristic work shot on a boat on a Swiss lake, contrasting the warmth of human presence (in part through a return to an updated take on the hand motif from The Image Book, relocated from the abyss of film history to a low-lit bar in the present day) with the overwhelming immensity of nature. All in all, the program didn’t try very hard to make the case for Aragno as a figure whose solo work can be seen as occupying a distinct territory from that of his work with Godard—but then, why should it? Aragno has gravitated toward and then pushed Godard’s work in new directions, crucially participating in and supplementing what may still be the most audacious ongoing artistic project in cinema.

Pelourinho, They Don’t Really Care About Us (Akosua Adoma Owusu, 2019)

A few quick words on some of the other standout short works that premiered in Rotterdam: James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s latest, This Action Lies, builds upon the Duchampian foundation laid by his last short, Indefinite Pitch (2016), pairing still images of what appears to be a styrofoam cup of coffee perched on a stool with a confessional monologue that unspools on the soundtrack, examining the act of apologizing, the ontology of cinema, the metaphysics of observation, fatherhood, and a host of other topics across 30-some heady minutes. This Action Lies functions nicely as a sort of summary of the prolific Wilkins’s oeuvre to date, reorganizing his preoccupations (cinema, money, the everyday) while pointing ahead to potential new directions for the restless iconoclast. At one point in the film, Wilkins characterizes his approach, pace Jean-Paul Sartre, as “searching for a method”; this search has only grown in its vitality as he has found new (and often humorous) ways to reveal cinema’s myriad aporia. Likewise, Akosua Adoma Owusu’s Pelourinho, They Don’t Really Care About Us adopts a similarly meditative tone in its synthesis of historiography and travelogue. Taking as its point of departure a 1927 letter from W.E.B. Du Bois to the American embassy in Brazil, Owusu traces a connection from the plight of African American travelers in Brazil in the first half of the 20th-century to her present-day experience of the streets and architecture of Salvador, vibrantly captured in Super-8mm. She integrates footage from the Spike Lee–directed music video for Michael Jackson’s “They Don’t Really Care About Us” (1996), also shot in the Pelourinho section of Salvador, teasing out the underlying social tension of her presence. That video’s production was famously maligned by the Brazilian government, who were concerned that Jackson and Lee would shine too bright a light on rampant poverty in Salvador and Rio de Janeiro (though the cities’ residents were all too happy to serve as MJ’s extras), and the shoot itself was a massive spectacle that required over a thousand policemen to seal off the favelas being used as its locations. A multilayered reflection on what it means to be treated like a foreigner both at home and abroad, the visually sumptuous Pelourinho, They Don’t Really Care About Us prompts us to consider the enduring inequality known by blacks in the U.S. and Brazil alike and what an artistic intervention against it might look like.

Mal-Fekata (Hasabie Kidanu, 2017)

The festival’s lone celluloid-only group program, “The Skin Is the Film” abounded with material delights, from Esther Urlus’s texturally rich study for a battle (partly developed in horse urine, natch), to Hasabie Kidanu’s collage-like approach to low-key city-symphonizing in Mal-Fekata (a spellbinding confluence of 16mm images shot in her native Addis Ababa, Ethiopia), to Gautam Valluri’s Midnight Orange, which recalls Gregory Markopoulos in its rhythmic exploration of the architecture of the Paigah family’s tombs in Hyderabad, India. But the cake was likely taken by Luis Macias’s dual-projector performance, the eyes empty and the pupils burning with rage and desire, an imageless, silent, and totally singular experience in which Macias himself burned the emulsion off strips of 16mm running through the projectors, pushing the spectator past the narrative and representational layers of cinema to engage fully with the medium’s physical basis as it approaches the point of (literal) disintegration. I sat beside Macias’s station during the performance, and if the fumes from the burning celluloid wind up giving me cancer, so be it.

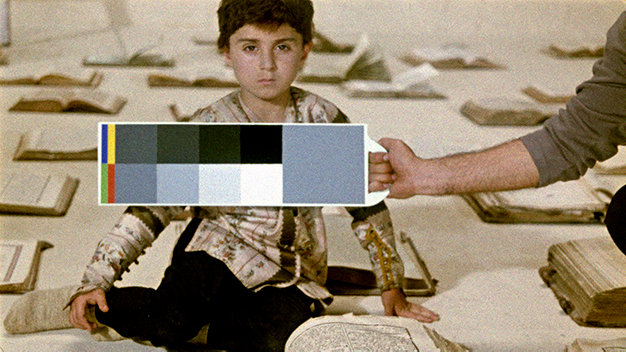

Outtake from The Color of Pomegranates (Sergei Parajanov, 1969)

There were a number of art exhibitions within the festival, including Blackout, curated by the film programmer Julian Ross, which showcased recent works for slide projector (including an installation and a performance by the filmmaker Cauleen Smith, whose feature debut, Drylongso [1998] also screened at the festival from a new 16mm print, while a program of her experimental short films was screened elsewhere in the festival as well), thought-provokingly scrutinizing the relationship between technological obsolescence and historical memory. A rather unimpeachable highlight was an exhibition of newly restored outtakes from Sergei Parajanov’s 1969 masterpiece The Color of Pomegranates, which were presented on video monitors embedded within tables in a church replete with a mammoth organ, creaky stairs, and an atmosphere lousy with the scent of incense. Restored from the original camera negatives by the heroic restorationist Daniel Bird, these outtakes peel back the top layer from Parajanov’s practically unsurpassed compositions to reveal not only that, yes, these otherworldly images were obtained in this very world that we ourselves live in (signaled by a jeans-clad technician on a ladder in the background fixing a light amid an otherwise transporting tableau), the final product to which they amounted was deeply informed by the decisions of the Soviet censors. Bird’s ongoing exploration of the “behind the scenes” machinations surrounding the work of one of cinema’s all-time great visual stylists promises to enhance Parajanov’s work, and this labor is already paying off: Bird also presented a program of newly restored short films by Parajanov—Hakob Hovantanyan (1967), Kiev Frescoes (1966), and Arabesques on the Pirosmani Theme (1985)—and the results were revelatory, helping to fill in the gaps of our understanding of his artistic development between Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1965) and Pomegranates. Hakob Hovantanyan is something of a warmup for Pomegranates, an associative and evocative study of the paintings of the titular 19th-century artist, while his move toward the cinematic fresco is encapsulated by Kiev Frescoes, cobbled together from footage intended for a feature-length work about post-WWII Kiev before the Soviet authorities ordered most of it destroyed. The Arabesques further develop Parajanov’s interest in the relationship between cinema and painting in the form of an intricately sequenced montage of details from the paintings of the Georgian outsider artist Niko Pirosmani. The art-historical function of this shorts program and exhibition within the context of a festival the scale of Rotterdam was immense, not so much providing a reprieve from weak premieres and uneven shorts programs as helpfully reminding us that it has never been easy to create work of enduring significance, that art has always entailed struggle and will continue to do so until further notice.

Dan Sullivan is a programmer at the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the co-editor of the Film section of the Brooklyn Rail.