Rep Diary: Seijun Suzuki

Branded to Kill

When the first retrospective devoted to enfant terrible filmmaker Seijun Suzuki hit North American shores in the early Nineties, his name was virtually unknown outside of Japan, unless you’d caught his languid, period-set, doomed-romance-cum-art-house-ghost-story Zigeunerweisen at the Berlin Film Festival in 1981, where it was recognized with an Honorable Mention. A couple of his films had been made available on home video in the U.S. via a specialty label curated by John Zorn, but only at Kim’s Video, and only if you didn’t mind watching them without English subtitles. David Chute wrote one of the first English-language articles about Suzuki for FILM COMMENT’s January/February 1992 issue, and that essay—which covers six films screened at the Vancouver International Film Festival retrospective the previous October—was reprinted in a 1995 collection of essays edited by Tony Rayns and Simon Field. All of these more or less printed the legend of Suzuki as a lone visionary toiling away under the thumbs of soulless corporate bosses at Nikkatsu studios in the Fifties and Sixties, struggling to make some kind of artistic statement out of the assembly-line scripts which were assigned to him.

What a difference two decades make. In the years since Suzuki’s “discovery” by Western critics and festival programmers, scores of other genre fantasias have emerged from the vaults of Nikkatsu and been released onto English-friendly home video or given wider-ranging retrospectives at film festivals, like Mark Schilling’s pioneering 2005 series at the Far East Film Festival in Udine, which later toured North American venues under my custodianship. To many cineastes’ surprise, other pulp action films were unearthed which came very close to approaching the best of what Suzuki had created, some of them even surpassing his efforts, and many of them by genre workhorses whose careers outside of a notable film or two were nothing more than routine. Works by filmmakers like Toshio Masuda, Koreyoshi Kurahara, Takashi Nomura, Yasuharu Hasebe, and others came to light, many of them featuring the same actors or technicians Suzuki had relied on, and they’ve rightly taken their place among the genre classics of the era, with dozens now available on home video, thanks to the efforts of The Criterion Collection, Arrow Video, and other companies.

With this accumulated 10 years of film history and enhanced availability in mind, film curator and author Tom Vick has taken another look at Suzuki’s career in his fascinating Time and Place are Nonsense: The Films of Seijun Suzuki, which is also surprisingly the first book-length study of the director in English. In conjunction with its publication last month, Vick has also programmed a traveling retrospective of some of Suzuki’s best-known—and least-known—films, ranging from program-picture potboilers to eccentric experiments in storytelling and style, and the series begins at the Film Society of Lincoln Center on November 6.

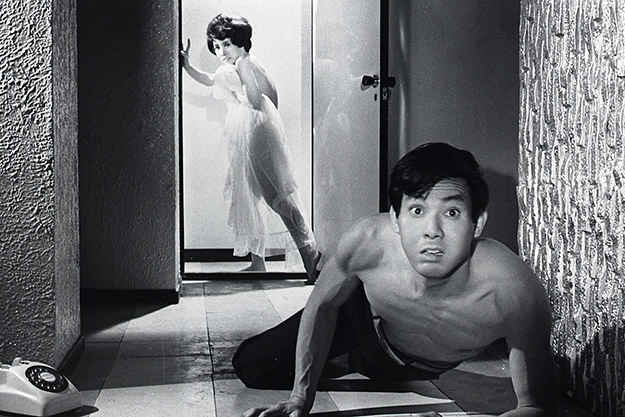

Eight Hours of Fear

The 21-film selection of Action and Anarchy: The Films of Seijun Suzuki is especially welcome in that it covers his early pulp movies and his mid-period, studio-bound experiments (including his final few titles for Nikkatsu), as well as films produced during his comeback years, which include both oddball commercial one-offs and more serious works aimed deliberately at an art-house or international festival audience. As important as it is to finally dispense with the assertion that Suzuki was the only artistic filmmaker at Nikkatsu during their heyday, it’s also imperative to look beyond the films which supported the theory of Suzuki’s “frenzied, voluptuous excess” (to quote one critic)—which, in reality, exists in only a handful of his works and can just as easily be found in films by other directors of the era. So while Tokyo Drifter and Branded to Kill, for example, are as wonderful and thrilling as ever, there are also many other films deserving of audience attention that can only be seen in this series.

Earliest among these is 1957’s Eight Hours of Fear, Suzuki’s fifth film as a director, and it’s as pitch-perfect a distillation of pulp cinema as the best works of Samuel Fuller, Andre De Toth, or Anthony Mann. The plot could be written on a cocktail napkin: an agitated busload of passengers schlepping across the mountains between train stations due to a disruption of service meet up with two violent convicts on the run. While half the film is a riff on Lifeboat, with a crazy quilt of personality types at each others’ throats in the confined space, the climax stops the bus for a tense standoff between the passengers and the convicts, resulting in some surprisingly violent episodes and a turnabout for many of the stock character types. Nobuo Kaneko, later the villainous and cowardly mob boss in Kinji Fukasaku’s Battles Without Honor and Humanity series, shines in an early leading role as a prisoner being escorted by police who isn’t quite what he seems to be at first.

Smashing the O-Line (60, aka Clandestine Zero Line) exemplifies the kind of Japanese crime film that could never have been made in America at the time, and although it amps up the sex and violence to a degree surprising for the era, Suzuki nevertheless delivers a jazz-inflected program picture with enough nuance and style to defy the assertion that his best works were made in opposition to studio mandates. Hiroyuki Nagato, the lead in Pigs and Battleships, is Katiri, an utterly amoral newspaper reporter who’ll literally do anything for his story; the opening of the film sees him turning his drug-dealing girlfriend over to the cops moments after leaving their post-coital bed, then delivering the scoop to his editor. The story develops into a complex web of human slavery, drug trafficking, and the rivalry between Katiri and a more humanistic colleague, both of whom are eventually shanghaied by the criminals, and it’s sleazy, thrilling, and full of contempt for humanity throughout. A bitter pill perhaps, but possibly the best film from the first half of Suzuki’s studio career.

Gate of Flesh

Already on home video but well worth another look are Suzuki’s mid-period masterpieces Youth of the Beast (63), his second collaboration with chipmunk-cheeked muse Jo Shishido, and a lunatic crime film that still manages to (barely) hold together its overly-complex plot; and 1964’s Gate of Flesh, possibly Suzuki’s most prestigious film during his Nikkatsu years, adapted from a popular novel by Taijiro Tamura. It also stars Shishido, this time as an army vet on the run from the police who holes up with five prostitutes in a postwar Tokyo black-market shantytown, igniting sexual tension within what was already a tenuous partnership. Melodramatic in both tone and style, the film succeeds by excess. The much-remarked-upon color-coding of the women’s costumes, the abundant nudity and S&M sequences, and the histrionic performances by foreign actors in the cast all contribute to the overall effect. It’s a operatic riot of color and motion, with breathtaking production design by frequent Suzuki collaborator Takeo Kimura, and a top-notch cast, who are constantly covered in sex-sweat and slum-grime.

Speaking of operatic, Suzuki’s 1966 Bizet riff Carmen from Kawachi casts Gate of Flesh’s female lead, Yumiko Nogawa, as the titular heroine, who travels from the countryside to the city in search of fame and men, not necessarily in that order. Satirical and stylish, it’s largely unseen in the U.S., despite being made just prior to the director’s much better known Tokyo Drifter. Nogawa also stars in Suzuki’s devastating Story of a Prostitute (65), again based on a novel by Tamura and chock-full of sex, violence and degradation, as Nogawa’s character is sent to Manchuria as a “comfort woman” to service soldiers on the front. There she finds herself trapped between two lovers, a brutal lieutenant who wants to own her, and his more humanistic subordinate. Unsurprisingly, things don’t turn out so well in the end for any of them.

Often cited as early examples of Suzuki’s playing with form due to his boredom with the rote scripts he was handed by the studio, Kanto Wanderer (63) and Tattooed Life (65) unfortunately don’t hold up as well under scrutiny as they did 10 years ago, when they were among the few Suzuki titles available in English. The walls of a set fall away to reveal a blood-red artificial backdrop during the climax of the former, and it’s the floor that disappears during a fight scene in the latter, but in comparison with Suzuki films where the lunacy is woven throughout the entire endeavor, these showy devices seem only to call attention to the deficiencies present elsewhere in the films. While Kanto Wanderer begins admirably as a satire of traditional ninkyo, or honorable yakuza films, with a gaggle of schoolgirls ingratiating themselves with the gangsters like a giggly fan club, it quickly devolves into a then-standard story of a dishonorable boss causing trouble for a stoic hero, who must choose between duty and personal desire to save the day. Tattooed Life treads similar ground, and by the time it was made, rival Toei studios had cornered the market on this type of film, producing yakuza movies with just as many clichés but better overall execution. For uniquely Suzuki-style yakuza, Tokyo Drifter’s white-suit-clad, song-warbling matinee idol Tetsuya Watari or Branded to Kill’s rice-sniffing hit-man-with-a-death-wish Jo Shishido are definitely the better way to go.

Fighting Elegy

Sandwiched between these two style-drenched crime films, though, is one of Suzuki’s most overlooked titles, despite being readily available on DVD: the 1966 black-and-white, satirical antiwar film Fighting Elegy. Phalluses and crucifixes rule the imagination of Kiroku, a hyperactive student whose military training is continually interrupted by the sexual fantasies he has about the Catholic daughter of the family he’s staying with. While the country ramps up for war with China, militarism and adolescent sexuality are conflated by Suzuki and screenwriter Kaneto Shindo until the only way to practice abstinence is through violence, both personal and political. It’s one of Suzuki’s best films, and deserves a place among the finest works of cinema satire, alongside the best of Yasuzo Masumura, Robert Altman, or Billy Wilder.

Satire eventually devours itself in the earlier of two little-known masterpieces screening in the series, Suzuki’s 1977 comeback film A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, made for Shochiku 10 years after he’d been fired by Nikkatsu following the Branded to Kill debacle. The film’s cynical screenplay was provided by Atsushi Yamatoya, a provocateur who’d written and directed some independent pink films before he started at Nikkatsu, eventually co-authoring Branded to Kill with several others (including Suzuki) under the pseudonym “Hachiro Guryu,” then directing its Roman Porno remake in 1973 as Trap of Lust. Adapting an original story by prolific sports manga author Ikki Kajiwara, Yamatoya’s script follows the rise of Reiko, a fashion model groomed to become a professional golfer based solely on the needs of an advertising agency that wants to counter a foreign athlete’s rising fame with something home-grown. Her manager and lover (Yoshio Harada) watches with amusement as she becomes a TV star and wealthy celebrity, complete with beautiful but emotionally empty home in the suburbs.

But things turn significantly darker halfway through, when a neighbor who initially idolizes Reiko stages a car accident to put the star in her debt, and then emotionally, and later physically, tortures her in increasingly sadistic games of wish-fulfillment, celebrity worship, and blackmail. It’s as biting a condemnation of fleeting and meaningless celebrityhood as anything produced in Hollywood, and one of Suzuki’s most successful fusions of his chaotic style with a script that supports those visual ambitions. (For a much more comprehensive consideration of the film, you can’t do much better than Grady Hendrix’s essay here.)

Capone Cries a Lot

Immediately after Tale, Suzuki made Zigeunerweisen, which came to define the latter half of his career and first sent him overseas to international film festivals and critical adulation. Adapted from a 1951 novel by screenwriter Yozo Tanaka, another former member of Branded to Kill’s “Hachiro Guyru” composite, and also responsible for writing Yamatoya’s Trap of Lust, it began what’s known as Suzuki’s “Taisho Trilogy,” a series of films set during the short era of modernization and democracy preceding Japan’s military buildup and entry into World War II. It was also a time when the arts flourished in Japan, heavily inspired by foreign influence in a way that hadn’t been possible before. Kagero-za followed in 1981 and the trilogy was completed in 1991 with Yumeji (both also written by Tanaka). All three are independently produced, heavily theatrical dramas about artists, writers, ghosts, and suicides with deliberately fragmented stories and irrational logic. Filled with artifice and enigmatic dialogue and characters, the films are rarely seen on the big screen, but their riddles may defy even the most attentive viewer.

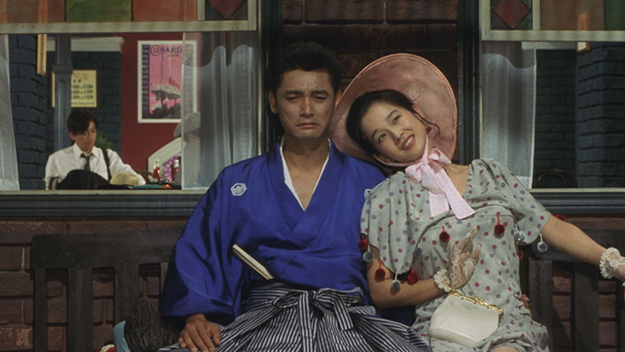

Even more obscure than A Tale of Sorrow, but more accessible than the Taisho Trilogy, is 1985’s Capone Cries A Lot—Japanese songs, American gangsters, slapstick comedy, and psychedelia mixed with a surprisingly serious criticism of discrimination and American imperialism (not surprising given that the screenplay was once again co-written by Yamatoya). It’s possibly the ne plus ultra of Seijun Suzuki provocations, and must be seen to be believed. A traditional naniwa-bushi singer, escaping an angry yakuza whose wife he’s stolen, moves with her to Prohibition-era San Francisco and meets up with a good-natured Japanese gangster named Gun Tetsu, who uses the singer’s knowledge of sake-brewing to make bootleg booze. This draws the attention of Al Capone, and when the pair travel to Chicago to meet with him, the singer, now calling himself Kaiemon, believes that he’s being taken to perform songs for the President of the United States.

Made entirely in Japan, and with dodgy English-language acting by both the Japanese and American performers, it’s an explosion of color and anachronistic costumes and hairstyles, with Kimura’s set design repurposing a Japanese amusement park to approximate the West Coast of the United States. Despite some dicey racial incidents early on, the film eventually provides Kaiemon with a Caucasian girlfriend, has him writing naniwa-bushi songs about the plight of Native Americans and the Sand Creek Massacre, and shows him being sent to an internment camp during the war. Non sequitur editing and deliberately artificial set design and acting—hallmarks of Suzuki’s works throughout his career—are here used to maximum effect, and by the time Kaiemon dresses up as Chaplin and starts doing a Little Tramp routine, you’ll be far too amused to care whether it makes any sense or not. As is the case with many of Suzuki’s best films, you should just sit back and enjoy the ride.

Action and Anarchy: The Films of Seijun Suzuki screens November 6 to 17 at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.